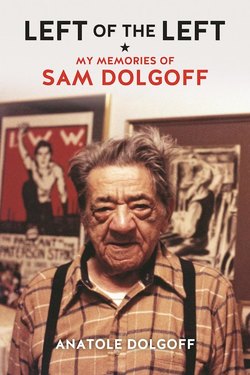

Читать книгу Left of the Left - Anatole Dolgoff - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5: Sam Is Bounced from the Socialist Party

ОглавлениеSam’s disillusioning experience with the Socialist Party and its response to the Red Scare led him to question the basic premise for the existence of the Party—and beyond that, the basic premises of “capitalist democracy” itself. His critique was intuitive and expressed in the unpolished fashion of an unlearned working-class kid. Nevertheless it had a powerful internal logic.

How can one expect those who have spent a lifetime trying to gain power within an unjust system—with all the compromises, connivances, and betrayals that takes—to fundamentally change it? Far from opposing the capitalist system, the Socialist Party reinforced capitalism by siphoning off discontent into the same harmless channels advocated by the Democratic Party: cheaper subway fares, lower prices, workplace reforms, etc. In fact, the Democratic Party was more effective at these things. Eschewing its revolutionary ideals, the Socialist Party had become capitalist democracy’s poor relation.

And what of this vaunted “democracy”? You elect a president who, like Wilson, campaigns for peace and turns on a dime to declare war—what’s more passes laws that compel you to fight whether you agree or not, and other laws that suspend the Bill of Rights to imprison you if you object. He can keep you vindictively in prison or pardon you magnanimously as he chooses. He can bestow privileges on one segment of the population and pursue policies that punish others. He holds in his person dominion over a hundred-million human beings. In what sense, the young Sam asked, does a president differ from a king?

Ah, you say, the president is not a king because he cannot do these things without consent of Congress. But what is a Congressman, after all? How few of them there really are! Can one individual truly represent the interests of five-hundred-thousand people—or in the case of a senator, an entire State? Obviously not; he represents himself alone. Yes, Congress as an institution may oppose a president’s policies and act as a brake on his ambitions, but only to further its own interests; it constitutes a class unto itself. To paraphrase Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Congress is, with the president, “a king with six-hundred heads.”

But surely, you may say, this is a gross caricature; these people are elected. You can turn them out if they do not represent you. Yes, Sam would say, you—or, more accurately, an electorate involving vast numbers of people who may or may not share your views—have the right to bring in a fresh pack of kings every few years (and how few of them are really exchanged, and how minimal are the policy changes!). But ruled you are, make no mistake about that. Why, he asked, should one support a system that rules over you? Electoral politics is a fraud—and worse than that pernicious, because by fostering the illusion of freedom it seduces people into participating in their own enslavement.

What of civil liberties, you counter? Surely freedom of speech and other guarantors of human rights differentiate democracy from tyranny, one might say, by definition. Surely that makes our government—and similar democracies—worthy of support. However, Sam would insist, this line of thinking confuses matters by equating Government and freedom. After all, aren’t all these cherished rights protections against the power of Government, or as he called it the State? These rights are not granted by the State. They were—are—won by struggle against the State, as they were against kings, and they are in constant danger of being usurped—as indeed they are whenever the State feels itself threatened. The difference between a democracy and tyranny is that, in a democracy, the State does not have the power to completely impose its will.

There is an old counter to Sam’s critique: One may call it “the human nature” ploy. Human beings are by nature selfish, predatory, and often violent. Government is needed to keep the various factions from one another’s throats. It is needed, despite flaws and imperfections, to prevent descent into chaos and barbarism; it is necessary for the proper functioning of civilized society. This justification Sam held in contempt; because, he said, if human beings cannot be trusted to settle their own affairs rationally and peacefully, then certainly they cannot be trusted to elect others to do these things for them. The only solution is absolute tyranny imposed upon them, for the more freedom granted the greater the chaos and barbarism. However, a State-directed tyranny turns out in fact to be no solution to violence and chaos; for, far from preventing violence, the State monopolizes it in the form of police and the military, with disastrous results too numerous to mention. How can one deny this, Sam asked, when millions of WWI dead serve as a fresh example? Indeed, the authority of the State rests on violence. Threaten that authority and see how peacefully it responds! The young Sam, having knocked around more than most adults in a lifetime, having seen the best and the worst, did not take a simplistic view of human nature.

Economists, philosophers, and political scientists have made much of the differences between Capitalism—the private ownership of the means of production and distribution of goods and services motivated by profit—and the State. Sam chose to concentrate on their similarities. For arbitrary authority is at the core of each system. The typical capitalistic enterprise is an economic tyranny. The employee serves at the pleasure of the employer under his conditions and can be hired or fired at will. The worker has no say in the management of the enterprise or the dispersing of profit, which usually goes to absent shareholders who have not put in a day’s labor and have nothing to do with the enterprise. The entire business can be sold or closed down from under him without a whisper of consultation or even notice. If he doesn’t like the set-up he can quit—his sole “liberty”—and seek work elsewhere. If he has the wherewithal or good luck, he may better his lot, while the job he has left is filled by another slave. And a slave the worker remains, for he must submit to economic tyranny whether he stays or leaves.

“The essence of all slavery consists in taking another man’s labor by force. It is immaterial whether this force be founded upon ownership of the slave or ownership of the money that he must get to live.” These words are not Sam’s, but those of Leo Tolstoy. And Tolstoy was not alone in this view; it is why the radicals of his day referred to Capitalism as wage slavery. Sam came to view the whole of dominant society—the whole of centralized authority, be it the State, the Capitalist System, or organized hierarchal Religion—as a vast moral crime. And it is this moral crime that the dispossessed of the world must oppose.

These were not the beliefs of a good Socialist Party member, but Sam expressed them with accelerating vehemence and force, to the extent that the officers of the Party, and not a few rank-and-file members, accused him of disrupting the functioning of the organization. The upshot of Sam’s sojourn through the Party was that he was put on trial for insubordination and expelled. Decades later he would exclaim with a droll smile that the Party was right to do so—though not so much for his being insubordinate as for asking inconvenient questions. Hardly Galileo facing the hooded Inquisition, he welcomed the trial, because it gave him the opportunity to expound his views. “After the trial, one of the judges came up to me and said, ‘You know, you are not too bad. In fact you put up a pretty good defense, as far as things go, although your case is hopeless. I am going to give you a tip. You are not a socialist. You are an anarchist. You belong with the crazies.’ So I asked him, ‘What is their address?’”

I doubt the judge gave Sam an actual address, but he and a number of other failed YPSLs found their way to “a dingy little loft on Eighteenth Street and Broadway near Union Square,” headquarters of the anarchist periodical Road to Freedom. “We were heartily welcomed and without membership qualifications invited to attend group meetings and participate in all activities. I was overwhelmed to learn that there existed a different, anti-statist international…movement diametrically opposed to authoritarian Marxism.”

Sam had found his home.