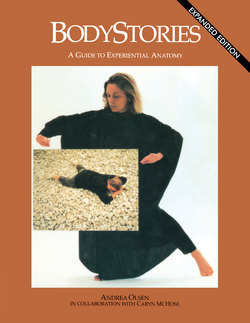

Читать книгу BodyStories - Andrea Olsen - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY

3

PROPRIOCEPTION AND SENSORY AWARENESS

How do we register body position in space? Without looking at your body, take a moment to observe how you are sitting. How do you know where your feet and arms are in space, the tilt of your head, the curve of your spine? Throughout your body are sensory nerves with specialized receptors to record muscle stretch, pull on tendons, joint compression and the position of your head in relation to gravity. These nerves are referred to as proprioceptors (“self-receivers”), and they give us our kinesthetic sense. Proprioceptors are essential for movement coordination and thus maintain continuous input to the central nervous system for interpretation and response. Proprioceptive receptors can be found in the skeletal muscles, the tendons in and around joints, and the internal ear. Muscle spindles tell us about muscle length, golgi tendon organs detect muscle force and the pull on tendons, joint receptors monitor compression in our joints, and maculae and cristae in the inner ear apprise us of equilibrium. The receptors must transform a stimulus from the external environment into a nerve impulse to be conducted to a region of the spinal cord or brain in order for it to be translated into sensation.

The somatosensory cortex of the cerebrum has a precise map representing sensory information from all parts of the body, and works in conjunction with the cerebellum of the brainstem to maintain a continuous, cumulative picture of the body’s position in space. The cerebellum, in particular, is responsible for constant coordination and correction of posture, movement and muscle tone. Even more fascinating, it holds the image of where you just were, where you are now, and it projects where you will go next. Remember the sensation of reaching for a stair with your foot when there was none? Your brain projection was different from actuality. (See the Nervous System, page 119) Stimuli carried to the spinal cord may initiate a spinal reflex – such as a knee jerk reflex – without input from the brain; those carried to the lower brainstem/cerebellum initiate more complex, subconscious motor reactions such as a reflexive postural shift to relieve muscle tension; sensory impulses which reach the thalmic level of the brain can be identified as specific sensations and can be located crudely on the body such as awareness of generalized pain or tension; those reaching the cerebral cortex can be located clearly on the body, such as awareness of position and movement, and connect with memories of previous sensory information so that the perception of sensation occurs on the basis of past experience.* For example, impact on the shoulder joint as an adult might provoke a protective response based on an injury from a fight in elementary school. Thus we carry a neuromuscular memory of our personal bodystory. Any body part can possibly be brought to our conscious attention with practice; it can also, fortunately, be left to provide information for body functioning without our awareness. Refined movement skills such as partnering in dance, an efficient tennis serve, and a surgeon’s or pianist’s hands in action, necessitate a highly developed kinesthetic sense.

Choice

A thirteen year old wildlife enthusiast was teaching me to handle a milk snake. I like snakes, but as soon as I saw its diamond-patterned body and flashing tongue, I tightened my muscles and stepped back. “The key to holding a snake is never to squeeze it or hold it too tightly,” my young instructor informed me. I let my muscles relax and felt the diverse sensations happening throughout my body. Then I could see the snake more clearly and respond to its particular movements; I could act rather than react. In the moments between perception and response, I had choice.

❖

At a workshop with Nancy Stark Smith, one of the founders of Contact Improvisation, I was having trouble releasing my weight to be lifted by (or to lift) my partner. I held low level tension in my body all of the time to protect myself. “Tension masks sensation,” she said to the class,” and sensation is the language of the body.”

❖

“When I became addicted to running,” a friend said, “I stopped. At first I was satisfied with five miles a day, but when I wanted more after twenty miles (when I couldn’t live without it, when my life focus began to be shaped around my passion for my physical high), I knew my need was out of balance.” This moving in response to the sensation of moving is referred to as “motoring” in the evolving language of dance: We feel ourselves move, want more movement, move, want more movement, until we are carried along by the sensory-motor loop, a self-propelling response between sensory input and motor response. Physically it is fun to do because of the satisfying quality of endless motion. It feels great. In shaping a healthy life, however, (or a dynamic performance for a dancer) it can be limiting because it involves so little of our potential. My friend had been caught in the sensory-motor loop, and he recognized that it was keeping him from a dimensional life.

❖

Erick Hawkins, a 73 year old pioneer of modern dance was reflecting on his years of teaching and performing. “One of the foundations of my technique,” he said, “is that tight muscles can’t feel.”

Photograph: Erik BorgMiddlebury College Dancers

Sensory receptors of the skin: A. Krause corpuscle registering cold B. Pacinian corpuscle registering pressure and vibration

The general and primary senses work in conjunction with the proprioceptors to monitor body awareness. The general senses include receptors for touch, pressure, vibration, cold, heat, and pain. They are located in the skin, the connective tissue and the ends of the gastro-intestinal tract; pain receptors are found in almost every tissue in the body. Visceroceptors, located in the blood vessels and organs, provide information about the internal workings of the body. Again, sensory information arises from the peripheral nervous system and is directed into the spinal cord, and then to higher centers in the central nervous system. If information reaches the highest level, the cerebral cortex, conscious sensation may occur. Some areas of the body such as the lips and hands are densely packed with sensory receptors, and others such as the trunk and thighs have few. Specific nerve ending receptors include: Pacinian corpuscles registering deep pressure and vibration; Ruffini’s end organs for deep, continuous pressure and joint compression; Merkel’s discs, Meissner’s corpuscles, and hair end organs for light touch; Krause corpuscles for cold, Ruffini corpuscles for heat; free nerve endings for pain (and light touch).

The primary senses have specialized receptors for vision, hearing, smell and taste located in specific organs in the head (eyes, ears, nose and tongue). They project information to related lobes of the cerebral cortex: the occipital lobe, temporal lobes, and frontal lobe respectively. Awareness is selective: we can use our primary sense organs to listen for a baby’s cry as we talk, or watch the expression on our listener’s face, or smell bread baking in the kitchen, or taste the chewing gum in our mouth, or experience all of the above simultaneously. We choose where we focus our attention by our intention. As movements or stimuli become familiar, awareness of sensation diminishes. For example, I may feel a chair when I first sit down, but this awareness passes quickly. Nerve endings adapt, that is, they cease registering information or “firing,” at different rates. Crucial receptors, such as those associated with pain, detecting chemicals in blood, or body position adapt slowly. The more developed and thorough our capacities for receiving and responding to sensory information, the more choices we have about movement coordinations and body functioning. ❖

TO DO

Note:

Each of us has areas of the body which we “shut off” for various personal reasons, including childhood trauma, embarrassment, injury, or neglect. These areas may be numb – hyposensitive – resulting in a lack of sensitivity, or the response may be heightened – hypersensitive – resulting in a “ticklish” sensation (nerve endings which detect no recognizable pattern from touch and are surprised, producing the familiar hysteria and giggling). Hyposensitive or hypersensitive areas can be brought into a balanced body picture through touch, proprioceptive warm-ups, and body scanning which relax muscle tissues, increase blood flow, and generally equalize attention to include all sensations.

Body scanning is also a component of Vipassana Meditation. For information about this form, write the Vipassana Meditation Center, Box 24, Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts 01370.

Body scanning

20 minutes

Lying in constructive rest, or seated comfortably with your spine vertical: bring your awareness to the top of your head.

❍ Observe, with eyes closed, any sensation you feel on the top of your head. It might be a tingling, a vibration, an itch, a pain. It might be a feeling of pressure, heat or cold, the touch of air on your skin.

❍ Continue to observe any sensation you feel on the top of your head. (The repetition of the language helps to focus your attention.) If you feel nothing, just wait (while perception of your nerve endings gets more sensitive).

❍ Bring awareness to your face and scalp. Observe any sensation without judgment; the task is to feel what is really happening in your body, without evaluating whether it is good or bad, pleasant or unpleasant. Experience your body just as it is at this moment in time.

❍ Move your mind’s eye to your neck. Remember to give equal attention to any sensation which you feel on your neck – tingling, the touch of cloth on the skin, your hair as it brushes the surface.

❍ Continue to the right arm, the left arm, the back surface of the body, the front surface of the body, the pelvis, the right hip and thigh, the right lower leg and foot, the left hip and thigh, the left lower leg and foot. Bring your awareness to the soles of the feet.

❍ Finish by observing your breath as it falls in and out of the nose and the mouth, moves the ribs, and stimulates the skin of the lower back and belly.

❍ Slowly open your eyes; allow yourself to remain aware of sensation as you include vision.

Body painting

20 minutes

Lying comfortably on the floor, image a color of your choice which covers the surface you lie on.

❍ Begin very slowly to paint your entire body with this color by moving your body surface in contact with the floor.

❍ Be sure to touch every area of the body. Include: between the toes, scalp, eye sockets, behind the ears, under the chin, all surfaces of the pelvis, backs of the knees, wrists, armpits.

❍ You may use another body part which is already painted to stroke hard to reach areas. Take as long as you need; do a final body scan to ensure every surface is covered in paint.

❍ Begin a proprioceptive warm-up by following any impulses your body has for movement – a stretch of the arm or wriggling of the toes. Whatever feels good is “right.”

❍ Move nonrepetitively following the impulses of the muscles and joints to stretch and move.

❍ Pause. Imagine yourself as a painted sculpture. Rest.

Collage: Rosalyn Driscoll “Dawn Pilgrimage”

* Gerard Tortora and Nicholas Anagnostakos, Principles of Anatomy and Physiology, pp. 344-345. For further information see Deane Juhan’s “Skin as Sense Organ,” “Touch as Food,” and “Muscle as Sense Organ” in fob’s Body, A Handbook for Bodywork.