Читать книгу BodyStories - Andrea Olsen - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDAY

4

THE CELL

The cell is the fundamental unit of the body. The abilities of the cell to reproduce, to metabolize, and to respond to its environment, are basic to human life: creativity, processing, and responsiveness to change.

Cells have common properties but vary according to function in the body. Each cell is composed largely of water, the basic substance of the body. Water is contained within the cytoplasm of the cell which is concerned with metabolic activities such as the use of foodstuffs and respiration. The cell membrane differentiates the cytoplasm from the surrounding external environment and creates a semipermeable boundary governing exchange of nutrients and waste materials, and responding to stimulation. The nucleus supervises cell activity. The forty-six chromosomes in each human cell contain the genetic code for the individual body and for the specific functioning of each cell. Each nucleus, therefore, contains a master plan of the whole body. Individual cells have different functions; for example, a muscle cell contracts, a nerve cell transfers electrochemical signals, a fiber-producing cell produces connective tissue fibers. A collection of like cells of similar structure and function is called a tissue. Groups of coordinated tissues form structures (organs), which comprise a body system. For example, bone cells form bone tissue, which makes bones, which create the skeletal system.

The cell is the functional unit common to all body systems. For our study, we will differentiate seven body systems as defined by Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen: skeletal, muscular, nervous, endocrine, organ, fluid, and connective tissue. Although we can look at each system individually, it is important to remember that the body functions as an interrelated whole and that the systems balance and support each other.

The human body develops from the union of two cells, the sperm and the ovum. The fertilized ovum divides repeatedly to create many cells. Within a day or so of fertilization, the ovum differentiates into embryonic tissue layers: the ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm in that order. The ectoderm is the origin of all nervous system components and the skin; the endoderm, of the digestive tract and organs; the mesoderm, of the connective tissues (blood, bone, muscle, ligament, tendon, fascia, and cartilage). Thus, the skin begins from the same embryonic tissue layer as nerve tissue; the blood originates with connective tissue. Cells vary in their adaptability to change or healing, and in their rate of reproduction. For example, some skin cells reproduce through cell division daily, while a nerve cell may remain for a lifetime and heals slowly if at all. The skin is the external membrane of the body, a highly sensitive boundary between our body and our environment. Sixty to seventy per cent of lean body weight is water, and the skin literally keeps us from drying up. Two-thirds of this water is within the cells (intracellular) and one-third is between the cells (extracellular). The skin also maintains body temperature (through sweat), contains receptors of various sorts, and provides a responsive, protective covering. It forms orifices such as the mouth, the nose and the anus, leading to the passageways of the digestive system and the respiratory system which can be seen as extensions of the external environment.

Exchange

While attending workshops about experiential anatomy, I would sometimes get stuck. I put a barrier to learning around absorbing new information because I felt threatened by change and by opening to a group. One particularly tense day, the teacher talked about the cell. She described osmosis and the movement of fluids through the cell membrane. She looked around the room and said, “Remember, change is only a membrane away.” The tightness of my skin dissolved. Once relaxed, I could allow information to come and go, keep what was useful, and express my own ideas. By releasing my outer membrane, I could allow exchange.

❖

An instructor once said to a group of adults, “See if you can walk through the room without feeling responsible for anyone.” And also, “Within the cell, feel the movement in stillness. Within the group, feel the space in closeness.”

Oxygen, essential to cellular life, comes into the body through our nose and mouth and travels through the trachea to the lungs. As the diaphragm descends, the lungs are expanded by the inrush of air called inspiration. When the diaphragm releases, the lungs are compressed to expel carbon dioxide in a process called expiration. The oxygen is absorbed through the capillaries in the lungs and enters the blood to be pumped by the heart throughout the body. Arteries carry the oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the periphery. Each cell participates in the absorption of oxygen and the removal of waste materials in connection with a process called cellular respiration. Deoxygenated blood returns via the veins to the heart. Through this process, every cell is in connection with the outer environment and “breathes.”

Tension in any part of the body restricts cellular activity vital to healthy tissue. Through bodywork, we use the responsiveness of the cell membranes and the skin to heat, vibration, and touch to bring awareness and affect change. ❖

TO DO

Cellular awareness:

Image yourself as a single cell. Feel the boundary of the outer membrane. Be aware of yourself contained, as a single unit, with all parts of the body contributing to the whole. Allow exchange with the world around you. Notice what flows in, what flows out.

Cellular breathing

20 minutes

Lying in constructive rest with your hands on your ribs, eyes closed:

❍ Bring your awareness to your breathing. Feel the air coming in through your nose and mouth, passing down through the trachea in your neck, and filling the lungs inside your ribs. Feel all the ribs move as you breathe. In the damp, warm environment of the lungs, the oxygen is transferred from the air to the blood through tiny capillaries. This is “lung breathing.” Three-fifths of the volume of your lungs is blood and blood vessels.

❍ Feel the pulsing of your heart. Image the blood being pumped by the heart through the arteries, carrying oxygen from the lungs to every cell in the body. This absorption of oxygen and removal of waste materials through the cell membrane is called “cellular breathing.” Image the deoxygenated blood returning through the veins to the heart, and the process repeating. Place your hands on your belly and your ribs, and feel them both move as you breathe.

❍ Image the flow of oxygenated blood from your heart down into your belly. Let this continue through the hips and knees, and into the ankles and feet. Allow the flow to return like a wave from your feet to your heart. Feel the movement under your hands. Image the flow of fluids moving from your heart up through the neck and into the skull to bathe the brain, and back to the heart. Feel the flow out through your shoulders and elbows and hands, pooling in your palms and fingers and returning to center. Feel the continuity and constancy of flow through your whole body. Image the fluids moving simultaneously from center to periphery and from periphery to center.

Breathing spot

5 minutes

In constructive rest: roll to your side, flex arms and legs close to the body and continue to roll to a “deep fold” position: arms and legs tucked close to body, forehead on floor, spine curved.

❍ Place your hands on your lower back, just above your pelvis. Feel the movement of the skin and muscles as your breath enters the lungs and is released. The diaphragm compresses the abdominal organs and expands the back. We can call this area your “breathing spot.” Encourage its movement with each breath.

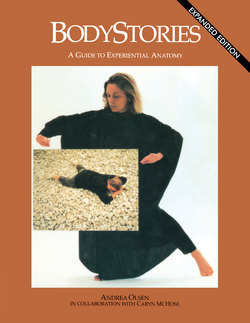

Photograph: Bill Arnold “Allan’s Boys”