Читать книгу BodyStories - Andrea Olsen - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

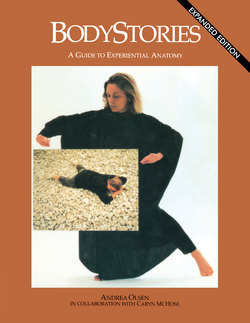

ОглавлениеPREFACE

TO NEW EDITION

Since BodyStories was published in 1991, I have received many letters from around the world. These writings reflect a global network of people attending to the body as subject, not as object, in their lives. People share their stories: a teacher in Sweden, students in Moscow, directors of a massage school in California. We are each part of a much larger framework of understanding, each adding our view.

BodyStories has also been printed in German and Italian. Teaching in these countries through a translator, I hear the ideas of the text in another language and notice the way words shape experience. At Middlebury College in the U.S. where I regularly teach, a Japanese dance student says, “In my country, there are so many words for ‘sensation,’ I don’t know which you mean.” A Norwegian student asks, “What is this word ‘sensation?’” As my understanding of the body deepens, I acknowledge the distance between experience and the words used to convey it.

In the seven years since BodyStories was published, I have remained fascinated by the body attitudes expressed in my classes and workshops. Ambivalence about our physical home remains disturbingly pervasive. Students creating body tracings in an art education course filled their life-sized outlines with expressive symbols of injury, abuse, and fear: scars for surgeries, a black ribbon around the throat, words such as “don’t touch.” One student summed up her experience this way: “It is odd to focus on my body, I’ve been abusing it all of my life.”

There are also cultural shifts affecting changes in our bodies. BodyStories was written before computers were commonplace. The increased stress generated by the speed and information-overload of these machines designed to help us save time, paper, and energy needs to be examined. Fatigued students, already feeling depleted of energy and constricted in their bodies, speak of fearing the aging process. Another area of concern is the commonplace usage of prescription drugs to get students through the rigors of academic life, beginning in grade school, high school, or college. The number of students who miss my classes “to get their medications adjusted” is startling. How do we respond? Of the forty participants in one Anatomy course, eight have mothers who have died of or are being treated for breast cancer. Some students write of parents who are anorexic or bulimic. Acknowledging these complex trends, I realize that the information in BodyStories is still timely; its function is to return us to ourselves.

On a positive note, the past decade has brought an increased awareness of bodywork techniques. When I arrived to teach massage at a birthday party, the first question from the thirteen-year-old girls assembled was, “What kind of massage? Shiatsu or Swedish or deep tissue?” Experiential anatomy is now offered in the curriculum of several colleges, and the number of pre-med students and health professionals in my courses and workshops increases annually. The popularity of contemplative practice techniques including meditation, yoga, and T’ai Chi stimulates scientific research about the integrity of body and mind. Interdisciplinary coursework in environmental studies acknowledges the interconnectedness of body and earth.

This dialogue between body and environment is a new theme in my own writings. After focusing intensely on the body for over twenty years, I now look around me and am curious about the context in which I live. Our intricate relationship with the environment should be obvious, but most of us ignore our fundamental connection to the air, water, soil, animals, plants, and solar system of which we are a part. Body awareness is a key component in developing a new relationship to our environment. It helps us to address the primary concern of our time, how best to live on this earth.

My colleagues originally involved in BodyStories also reflect this shift in interest. Caryn McHose now focuses on the early evolutionary forms, the origins of human experience in a much broader context. Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen speaks of identifying fluid at the moment that it is transitioning or flowing into or out of the cell. John Wilson explores connections to anthropology and world cultures in his new role as professor of Dance and International Studies. Gordon and Anne Thorne extend their studio in the heart of community to include farmlands through the Open Field Foundation – inviting connections between art, education and environment. Susan Borg teaches “inclusive attention,” the simultaneous awareness of self and surroundings. And Janet Adler directs her incisive intellect towards mystical experience. For each of us, engagement with the personal, interior landscape has led us to a broader view. As we continue listening to the stories of our bodies, we recognize both body and earth as home.

– Andrea Olsen, May 1998