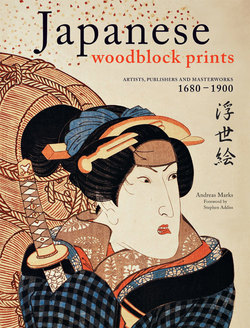

Читать книгу Japanese Woodblock Prints - Andreas Marks - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Buoyant World of

Japanese Prints

U kiyo, the “floating world,” was originally a Buddhist term, referring to the transient nature of human life and experience. The message was therefore not to cling to one’s desires, but instead to accept the flow of life without grasping. In the hedonistic urban culture of Early Modern Japan, however, the concept of a “floating world” was given a new twist. The new spirit proclaimed that if pleasures are only momentary, then let’s enjoy them as much as possible when they appear, much like the cherry blossoms that are all too soon lost to wind or rain.

1780s Shunman Far right panel from the first edition of an untitled hexaptych of women juxtaposed to the "'Six Jewel Rivers’” (mu tamagawa). Ōban. Publisher: Fushimiya Zenroku. Asian Art Museum, National Museums in Berlin. The complete hexaptych is illustrated in Genshoku

There is a fascinating paradox in ukiyo-e; these prints and paintings were created to appeal to the fleeting moment, much like pop songs today, and yet they are now prized as one of the most famous artistic products of traditional Japan. This has been due in large part to painters, collectors, and scholars in the West who were the first to recognize their artistic merits when they were still generally regarded as ephemera in Japan. It has been estimated that at one time as many as 90% of extant Japanese prints had been brought to Europe or North America, and some of the greatest collections now reside in museums in cities such as Boston, New York, and Honolulu. In recent decades, however, the flow has been reversed, with Japanese collectors and museums now buying prints from the West.

The first monograph on a ukiyo-e master in any country was Edmond de Goncourt’s Outamaro: Le Peintre des Maisons Vertes of 1891, and in the 118 years since, there have been more exhibitions, catalogues, and published scholarship on ukiyo-e than any other form of Japanese art. Yet much is left to be done, and this book by Andreas Marks offers not only reliable information on fifty major artists while establishing their historical progression, but also provides a much-needed recognition of the vital role played by publishers. These entrepreneurs not only commissioned artists to design prints or sets of prints and arranged for carvers and printers to complete the works, but they also were in charge of sales. Ukiyo-e was not a form of art created by the lonely painter in a garret, but rather a lively and up-to-the-minute visual medium for people at less than the highest levels of society. Just as we use posters and photographs as decoration and souvenirs, so did everyday Japanese enjoy prints, and without publishers the entire field could not have existed. Further, although they have often been ignored by collectors, the publisher’s markings are part of the artistic whole, just as the red seals of the artist provide visual punctuation to both paintings and prints.

What this extremely thorough and useful book helps to make clear is that ukiyo-e was a collaborative effort, rather different from most print-making in the West, with individual specialists taking the roles of designer, carver, printer, and publisher. They combined to create the supremely high level of the prints that continue to provide us with interest and pleasure today, long after the world in which they were created has floated away.

— Stephen Addiss, University of Richmond