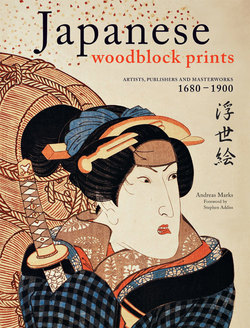

Читать книгу Japanese Woodblock Prints - Andreas Marks - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Unique Art Form

1870 Kunisada II “Hour of the horse” (Uma no koku), from the series “Twelve hours of attempts for hidden images year-round” (Jūni toki hitsushi no toshimaru). Left panel of an Ōban triptych. Publisher: Kiya Sōjirō. Japan Ukiyo-e Museum, Matsumoto.

Hokusai’s “Great Wave,” Hiroshige’s landscapes along the Tōkaidō road, Harunobu’s and Utamaro’s beauties from the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter, and Sharaku’s large-head actor portraits are just a few popular examples of the tens of thousands of woodblock prints that were published in Japan from the mid-seventeenth to the early twentieth century. This unique form of art—mass-produced colored woodblock prints—evolved and thrived only in Japan and there predominantly in Edo, present-day Tokyo. During a long period of peace known as the Edo period (1603–1868), the city of Edo grew to be a culturally and economically thriving metropolis with a dynamic society that enjoyed literature and kabuki theater as well as sexual entertainments, the famous “floating world” (ukiyo). A censorship system, put in place by the government to regulate the liberal but highly commercial daily life, could not suppress the rapid interest in woodblock printed images of actors and courtesans. Today widely known as ukiyo-e or “pictures of the floating world,” these prints developed from early black and white images to subtly hand-colored and then lavishly printed pictures. Often perceived as witnesses of an idealized, romantic past they are now highly treasured. In art sales, a well-preserved print, once sold for a few pennies as one of hundreds of impressions at the time of production, may now cost a fortune—much more than many paintings which are the only one of its kind.

In early modern Japan, this unique art form was an urban phenomenon of a purely commercial nature. Purchased by a large clientele of commoner townsfolk but also by aristocratic samurai, these prints were generally perceived to be a special product of Edo as indicated by the terms azuma-e (“pictures from Edo”) or azuma nishikie (“brocade pictures from the east”), and were popular souvenirs for visitors who came from outside Edo. Shops selling prints and books were established in many different parts of the city. Some offered a broad range of prints, while others specialized in specific items, such as fan prints. In general many of these shops were also active as publishing firms. Today, Japanese print collectors easily overlook the fact that these prints were not considered to be “fine art” during their time of production, nor were they considered to be the creation of a single artist working alone. They were in fact the joint product of a collaboration between several people, with the publisher in the center. The publisher was the decision maker, supervising the entire production process and marketing the final print.

A quintet of five interactive parties was involved in the creation of a print. First, was the artist who designed the image to be printed. Second was the engraver who cut the woodblocks for printing. Third was the printer who printed the sheets from the blocks. Fourth was the publisher who financed and oversaw the entire process—from discussing the subject of the print with the designer to putting the final print on the market. And fifth was the consumers, who played an active role also as their taste determined if the print would be a commercial success or not.

From the mid-seventeenth century onwards, prints were issued that focused on actors of the popular kabuki theater, beauties from the pleasure quarters, legendary samurai warriors and many other historical subjects. During the Edo period, tastes evolved and a demand for novel ideas resulted in the creation of new subjects like landscape prints and pictures of flowers and birds. It was the publisher’s responsibility and at the same time his challenge, to have a feeling for the trends of the time, producing his prints in unison with the consumer’s interests. The choice of the right print designer was vital. A designer could be brilliant and inventive—but if the consumer disliked his compositions or the choice of subjects, then the publisher most likely ended up in financial problems.

The large number of publishing firms existing in the Edo period reflects how vital and competitive the market was. Many publishing enterprises were short-lived, and little is known about most of them. During the three centuries that these prints were produced, well over a thousand publishers existed in Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto. Only two hundred left their trademarks on the prints, although we do not know their proper names. Of another 600 publishing firms, we know the names and locations, but that is about all. There are only about two hundred publishers for whom we know a few more details, for instance that they were members of the Picture Book and Print Publishers Guild (Jihon toiya). So, in the end we have detailed personal and historical information about only a few dozen publishing firms. The majority of print publishers and sellers were also active as book vendors. Several operated large shops and offered even publications of rival publishers who in exchange sold their publications. Such cooperation made sense in a bustling metropolis like Edo as it enabled a publisher to reach out to different locations in town in order to sell his products some distance away from his main premises without having to open another branch. Many publishers simply continued to feed the market according to the current taste, without taking the risk of trying out new themes or styles. If a publisher turned to lesser known print designers it was not always a sign of his willingness to support an unknown, possibly talented artist. Well-known designers charged higher prices for their images than lesser known artists. By engaging a popular designer the chance was raised that a publisher would be able to get his investment back, but he would have to invest more money upfront. Commissioning a lesser known print designer meant fewer investments but also assuming greater risk for failure of the operation. Those publishers who found the right balance between risk and security managed to survive.

1812 Kunitsugu The actor Nakamura Utaemon III as Kiyomizu Seigen in the play Kiyomizu Seigen omokage zakura, Nakamura Theater, III/1812. Ōban. Publisher: Suzuki Ihei. Asian Art Museum, National Museums in Berlin.

1787. Kiyonaga Illustration of Nishimuraya Yohachi’s shop, from the book “Colors of the Threefold Morning” (Saishiki mitsu no asa) Ōban Publisher: Nishimuraya Yohachi Museum of Asian Art, National Museums in Berlin

Even though the print designer was not the only link in the chain, he was crucial for the success of a print. The designer was the flagship and face of the product. He was allowed to sign his work, helping consumers to identify their acquisition even after time. Like engravers and printers, print designers were also considered craftsmen and they went through a system of apprenticeship. Starting at a young age, aspiring students first copied their master’s works, then completed sketches by the master and assisted in cheap book illustrations. It was up to the master to decide when a student was ready for his coming-out. After years of training, the master supported the student’s first self-work, so to speak, and the student was finally allowed to sign as well. The student received a name from the master with usually one syllable deriving from the master’s own name. Utamaro’s student Tsukimaro, for example, had the same “maro” in his name. Toyokuni’s famous students Kunisada and Kuniyoshi but also minor students like Kunitsugu (1800–1861) received his “kuni.”

Being the student of a well-known print designer naturally helped careers advance. Chances were higher that such students found publishers for their designs, but the fees they would receive at the beginning were still small. Accounts from the late Meiji period (1868-1912) that are most likely also applicable to the Edo period, state that young designers had to cover half or even the entire costs of cutting the woodblocks (sashikin) and only if the designer was promising would a publisher bear the costs himself. As a standard, print runs were counted in hai (lit. cups) consisting of two hundred impressions. The actual number of print runs depended on the popularity of the design and it was common to directly produce several runs of popular designers’ prints. If more than two print runs of the young designer’s work were sold, i.e. over four hundred impressions, he received his garyoō, the painting charge. In the 1870s, Kunichika, the leading designer of actor prints at that time, received one Yen (=100 Sen) for a triptych of four actors in half-length that was afterwards sold for six Sen. The same composition by another designer would cost 75 Sen, one quarter less.

Late 1790s Toyokuni The actors Nakamura Denkurō IV and Matsumoto Yonesaburō I in unidentified roles. ōban. Publisher: Nishimuraya Chō. Collection Arendie and Henk Herwig.

1861 Kunisada The actor Bandō Kamezō I as Koike Gokutarō in the play Chiyo no haru Tosa-e no saya ate, Ichimura Theater, II/1861, from the series “Stylish Mirror Reflections” (Imayō oshi-e kagami) ōban Publisher: Fujiokaya Keijirō Collection Arendie & Henk Herwig, The Netherlands

Publishers in general tried to offer a wide range of products, aiming at consumers with a wide range of interests. These products changed over time in accordance with the consumers’ interest and the technical development. Technical limits did not allow printing in color until the 1730s/40s and earlier prints were therefore hand-colored principally with an orange lead oxide pigment (tan-e) to make them more appealing. With the introduction of color printing with two blocks (benizuri-e, lit. “pink-print pictures”) it was not long until multicolor printing was achieved in 1765. The so-called “brocade prints”(nishiki-e), were well received and sprang up like mushrooms. In the following decades, the printing process was further enhanced by developing special printing techniques such as the use of mica, gold, and silver simulating metal pigments, graduation, embossing, and lacquer-like printing.

Originally, prints were single-sheet compositions and this continued to be the chief item until the twentieth century. By the second half of the eighteenth century, multi-sheet compositions developed (mostly diptychs and triptychs) showing a single image that evolved over all sheets. Occasionally, larger compositions appeared consisting of five, six, even twelve sheets. Every period was dominated by a specific format that appealed most to the majority of consumers. The narrow hosoban format was preferred for actor prints during the mid-eighteenth century. At the same time, prints of beautiful women were produced in the medium chūban format. At the end of the eighteenth century, the large ōban format became the principal size, mostly vertically for figures and horizontally for landscapes. Smaller formats existed as well in sizes deriving from the oban format (one half, one quarter, etc.). Fan prints, pillar prints, and other formats appeared on the market for specific purposes. Uchiwa-e, fan prints, were meant to be cut along their margins and glued on a wood frame in order to be used. Pillar prints (hashira-e) are long and slender in order to be hung in the house for decoration purposes. Of course this could be done with other prints as well, however, pillar prints, once mounted, were an ideal alternative to costly scroll paintings placed in the alcove (tokonoma) that was, and to a certain extend still is, traditional to Japanese houses.

The typical subject matters of these prints were popular kabuki actors (yakusha-e) and fashionable courtesans from the pleasure quarters (bijinga), which was initially conceived by the term “floating world” (ukiyo). These subject matters were not only captured on prints, the ukiyo-e, but also in paintings called nikuhitsu (lit. “flesh brush”). From the very beginning, erotica (shunga) was a major subject that was naturally high in demand in Edo because of its dominant male population, deriving, on one hand, from the many retainers that had to be present by law to guard the provincial lords in town, and on the other hand, from the rapid development of Edo itself that attracted many male laborers from the countryside. Edo was the largest town in the world at that time with a population of one million people—nearly seventy percent of them males. Bijinga and shunga were intertwined as they both addressed—from different aspects— the idealized icon of female beauty, derived from images of courtesans that were in fact prostitutes. Everyone had access to the pleasure quarters and their services but a hierarchy of courtesans developed and the high-ranking, hence very expensive, beauties were for most people unreachable. Their appearance in superb coiffures and luxurious garments became the motifs of bijinga. The initially full-length pictures of courtesans developed in the late eighteenth century to half-length, close-up portraits that focused even more intensly on their refined manners. As beauty pictures were such a popular subject, many of these prints were on the market and the publishers and print designers had to use new means to keep their products interesting to their clientele. Playful juxtapositions, imaginary comparisons called mitate developed as a new trend. The beauties were depicted in settings derived from another context and puzzles were created that evoked the interest of consumers and became the latest thing. A development that eventually would happen with actor prints as well, but at a much later period.

C.1869 Kunichika The actors Nakamura Shikan IV as Hisayoshi, Onoe Kikugorō V as Shibata Katsushige, and Bandō Kamezō I as Shōya Kikuemon in an unidentified play, Nakamura Theater, 1869 Ōban triptych Publisher: Yorozuya Zentarō Museum of Asian Art, National Museums in Berlin

c.1768–69 Harunobu “Snow” (Yuki), from the series “Elegant Snow, Moon, and Flowers” (Fūryū setsugekka). Chūban. Library of Congress. Suzuki 1979, no. 325-1.

The main purpose of actor prints was to portray the leading actors at the height of their performance and to offer the audience a souvenir of the theater experience to take home. The kabuki theaters were frequented by a sophisticated audience demanding new, exciting plays. Many plays were not repeated in exactly the same way but often presented as slightly different versions, sustaining an ongoing demand for new prints. The actors themselves developed stylized ways of performing (kata), speech patterns, and exalted poses (mie) that became their signatures and were passed on to the next generation along with their stage names. On actor prints, the actor’s could be identified by the crests (mon) depicted on their costumes or at other positions on the prints. In the first half of the eighteenth century, it became custom to inscribe the actor’s name on the print but in the second half the name disappeared again but the actors could be identified by their crest. In 1770, Shunsho and Buncho conceived half-length actor portraits that turned out to be very well received by kabuki aficionados. They are the principle developers of “likeness pictures” (nigao-e) that captured the unique personality and individuality of an actor, as opposed to earlier actor prints that concentrated on transmitting the beauty of the costumes and the lively motion on the stage. These half-length portraits took the form of striking bust portraits that hit the market around the turn of the nineteenth century. The output of actor prints increased significantly in the nineteenth century and the competitive market gave way to more technical refinements. The leading designers developed formulas as to how to depict certain actors best and reused these formulas to serve the high demand.

Early 1780s Koryūsai A young woman with the character yoshi on the obi and a scarf in the mouth, attended by a young girl. Hashira-e. Publisher: Nishimuraya Yohachi. Library of Congress. Pins 1982, fig. 385, and Hockley 2003, appendix III, N.12.

Besides beauties and actors many other subject matters became popular during different periods and several print designers specialized in certain subjects. Japan’s long tradition of heroic narratives and rich canon of legends found their way into so-called warrior prints (musha-e). Serial novelettes supported the interest in historical subjects and warrior prints occupied a respectable share of the market in the nineteenth century. Other literary sources found also their way onto prints, especially the eleventh century “Tale of Genji” (Genji monogatari) and its nineteenth century persiflage “A Country Genji by a Fake Murasaki” (Nise Murasaki inaka Genji; 1829–42). The popularity of the latter resulted in a new subject matter, the “Genji pictures” (Genjie), that were on the market from the 1840s until the early 1890s.

Landscape views, another popular subject matter in prints, derived from the Chinese theme of “Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers” (Jp. shōshō hakkei), first found in poetry before it became a painting motif. The “Eight Views of ōmi” (ōmi hakkei), or Lake Biwa, is its Japanese pendant that was first illustrated in prints in the first half of the eighteenth century. The travel and pilgrimage boom since the early eighteenth century supported the wide interest in guide books and landscape pictures. Views of the fifty-four stations along the Tōkaidō road (Tōkaidō gojūsan tsugi) that connected Edo with Kyoto, famous sights in Edo (Edo meisho), and views of Mount Fuji became the principal motifs for hundreds of print series.

The popularity of landscape prints and especially Hiroshige’s Tōkaidō series, provides an example of how publishers effectively returned their investment. For every design, publishers were alert as to how many impressions they had to sell to return their investment. In an ideal situation, a design got sold out and the demand continued to be high enough to produce another print-run. With every additional print-run that followed, publishers gained more profit than with the first, as neither the print designer had to be paid again, nor the engraver, as the woodblocks could still be used (at least for some time). The publisher usually only paid the printer for the production, including his work, the paper, the colors, and refinements, if any. After the engraver prepared the woodblocks, they became the property of the publisher and from some publishers we know that they kept their blocks for many years, waiting for an opportunity to reuse them. Sometimes blocks were brought to pawnshops, sold to other publishers, or the entire business was taken over by another publisher who then automatically came into possession of old blocks.

1899 Shusei “Yoshitsune and his Followers and the Terrible Storm in Daimotsu Bay” (Daimotsu-no-ura ni Yoshitsune shūjū nanpū). Ōban triptych. Publisher: Morimoto Shōtarō. Collection Arendie and Henk Herwig.

Hiroshige. 1857. “Sudden evening shower at Atake on the Great Bridge” (Ōhashi, Atake no yūdachi), from the series “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo” (Meisho Edo hyakkei). ōban. Publisher: Sakanaya Eikichi. Honolulu Academy of Arts: Gift of James A. Michener, 1991 (22745). Sakai 1981, p. 250, ōban no. 62.22.

In a few cases, the period of activity of a publishing house goes well beyond one hundred years, sometimes even over two hundred years. Tsuruya Kiemon, for example, started to produce books in the 1620s, turned then towards prints and his successors were active in this field until 1852. This long period outstretches by far the life of a single person and Tsuruya Kiemon, like many others, developed in fact from an individual publisher to a publishing firm that evidently operated over many generations. Usually, the leadership of the firm was passed on to the next generation who then took the predecessor’s name at the time of inheritance; much like the print designers and carvers did. It is not clear which generation of Tsuruya Kiemon had to abandon the print publishing business in 1852, but of another publisher, Daikokuya Heikichi, it is known that the publishing firm was in operation for 167 years until Heikichi V passed away in 1931.

In order to assist consumers in identifying the sources of their prints and to increase the possibility of making them returning customers, publishers marked their prints with their trademark. Publisher trademarks appeared in a wide range of styles depending on a number of factors like the time of publication. Today, this makes publishing seals a means to assist in dating prints from a time when date seals were not in use. The trademark on a print could have been a logo without an obvious connection to a specific publisher up to an elaborate description of the publishers’ merits including his full name and address. To return to the previous example Tsuruya Kiemon, Tsuruya Kiemon actually was the firm name, lit.: Kiemon’s Crane Shop. His trade mark was Tsuruki and the official name of the publishing house was Senkakudō (lit.: Immortal Crane Hall). His family name was Kobayashi, making his personal name Kobayashi Kiemon. The trademark on a print could incorporate any of these names and some publishers even created different seals for each print of a multi-sheet series.

Print series are important elements of this art form. Japanese woodblock prints developed from book illustrations, sequential, interconnected images that tell a story. These images became dissociated from the text and released from their bound form to be published as untitled sets called kumimono. At first, actor prints were not serialized but singularly issued after a successful performance. Series of actors only started to appear in the second half of the eighteenth century. In the beginning, prints of beautiful women proved to be more suitable for serialization and a wide range of devices like the Eight Views (hakkei) developed. Generally speaking, series are a clever invention by the publishers to bind consumers to their products. Titled series of prints with related designs were created to encourage customer’s loyalty. In the past but also today, consumers were inclined to complete the series once another design got available.

Kunisada. 1854. “Fifty-four— Dream of Ukihashi” (Gojūyon—Yume no ukihashi), from an untitled series “A Comparison of Present Genji Brocade Prints” (Ima Genji nishiki-e awase). Chūban. Publisher: Sanoya Kihei. Library of Congress.

In the following chapters, print designers and publishers are presented who created important single prints as well as print series from the mid-seventeenth up to the early twentieth century. Whenever possible, biographical details are given as well as lists of their major works. Representative works by each designer and publisher will provide visual access to them. The artists are listed in chronological order, thus creating a historical overview of Japanese woodblock prints from Kiyonobu (1664–1729) until Kokunimasa (1874–1944).