Читать книгу Japanese Woodblock Prints - Andreas Marks - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеartists

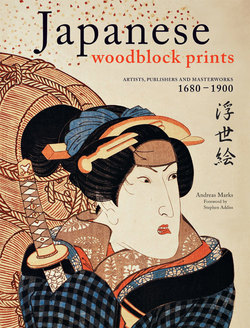

1892 Toshikage Memorial portrait of Yoshitoshi. ōban. Publisher: Akiyama Buemon. Private Collection.

This chapter contains the most prominent artists of Japanese wood-block prints between the late seventeenth and the early twentieth century. Artists like Utamaro or Kunisada were well-known during their day and considered masters of the form, and Sharaku, for example, is heavily sought by collectors today. Throughout the artists’ careers, they generally designed several hundred or even thousands of prints of different motifs and sizes for various publishers. Designs by Hiroshige, Hokusai, and others are still reproduced today using the same production techniques—but many fundamental details about the production process and the lives of the artists are now unknown.

Unsolved questions are how designs were conceived in general and how the actual printing process got started. Did an artist go to a publisher with a drawing asking to publish it, or did he send one of his disciples or someone else from his studio? Did a publisher or his clerk go to an artist with a suggestion for a print hoping that he would take on the task and create a unique design to his liking? We know that in some cases a third person, like a business owner, patron of an actor, poetry club, etc. financed designs but this seems to have been an exception rather than the general rule. Overall, the origin of a print seems to be actually comparable to that of a book today. An upcoming artist almost certainly went to a publisher himself, trying to convince him of the success of his design, much like today when a hitherto unpublished author tries to find a publisher for a book he has in mind. First, the young artist might have approached large publishing companies he already had contact with through his master and it is possible that his master recommended him or even turned down a project to support his disciple. If the first choice of publisher was not interested the young artist went on to see other publishers. The young artists’ initial payment was little if not nominal as he was still unknown and his design a sizeable risk to the publisher. If successful, the young talent was able to make himself a name and the publishers raised the payment and now started to come to him for designs. Over the years, a relationship between artist and publisher would be established and the artist would gain more freedom in his endeavors or be able to demand from the publisher the hiring of a specific woodblock cutter who he felt best for his design. To give an example of a long-term relation, Yamaguchiya Tōbei, the most active publisher in ukiyo-e history (who produced prints from c.1805 to 1895) issued in fifty-plus years, between c.1813 and 1864, around 700 different designs of Kunisada, the most active artist in ukiyo-e history.

Details of the design process are also not known today, starting with the inspiration, for example, for actor prints. How often did a print artist actually visit the kabuki theater to see a performance in order to be able to accurately capture a specific scene or an actor’s pose? Did he attend rehearsals or the openings? Did each artist go by himself or did several get together for a visit to the theaters? How deep was the rivalry or the companionship between the artists? How often did an artist visit the pleasure quarters to find inspiration for beauty prints and also for the very detailed erotic prints?

Biographical information about most of the artists is scarce as well. It seems that people from all classes could become print artists, if they were talented enough of course. Of Koryūsai, Eishi, Eisen, Chikanobu, and Kiyochika we know that they were originally from samurai families. Hiroshige’s and Kyōsai’s fathers were fire officers; Kiyonaga and Shigemasa were sons of booksellers; Yoshitoshi and Gekkō came from merchant families. Other artists like Kiyonobu, the son of an actor, and Eizan, the son of a Kanō-school painter, were already born into artistic families. In most cases, print artists started with their careers at a young age as apprentices of painters or other print artists where they learned how to draw. Hokusai is an exception as he was initially trained as a carver of woodblocks until he shifted careers when he was 18 years old.

For the majority of the artists we are forced to interpret what we can from their work as no reliable information exists about their social lives. One of the most trustworthy sources are grave stones, which can also bear the names of other family members. For instance, Kunisada’s oldest daughter married Kunimasa III who became then Kunisada II. Yoshiiku had ten children with his second wife, all but one of which died early. Kunichika’s unsettled lifestyle resulted in frequently changing partners as well as houses, but he probably did not move as often as Hokusai’s allegedly ninety times.

It is almost impossible to estimate the fame and wealth of a print artist. The most popular ones were certainly not treated as ordinary craftsmen. The name of such an artist was a guarantor for higher sales and they were, for example, commissioned to simply design the cover of a book while a lesser-known artist provided the illustrations for the inside pages. In the Meiji period, prints bear not only the artist’s signature but were ordered to carry also his family and given names along with his address. The address, however, is no indication of how large their properties were. A rare picture of an artist house is in a book on the Ansei Edo Earthquake of 1855, showing Kunisada’s large house with additional storage building, but it cannot be considered as standard for all artists because of Kunisada’s unparalleled success.