Читать книгу Churchill: History in an Hour - Andrew Mulholland - Страница 5

Youth: 1874–1895

ОглавлениеWinston Churchill’s childhood was to be a privileged one. Born into wealth and power, he would attend one of the most expensive schools in the country. He would, however, face very real difficulties. A strained relationship with his father and a tendency to rebel, meant that he was troubled. From an early age, too, there were signs that this boy was perhaps a little special.

When Lady Randolph Churchill unexpectedly went into labour three weeks early, she and her husband were staying with his brother, the Duke of Marlborough. The new baby was therefore born in the Cotswold majesty of Blenheim Palace, a huge mansion which Queen Anne had given to his ancestor, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. Marlborough had commanded the British Army at the decisive Battle of Blenheim in 1704. Baby Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill was born on 30 November 1874. He was to grow up steeped in British military tradition.

Winston’s parents lived at the margins of the old British aristocracy, and he hailed from a famous family. His father Randolph was a Conservative Party politician, representing the seat of Woodstock, where Blenheim is situated. The Churchills, however, lived in London. Randolph was an ambitious man and he wanted to be at the centre of political activity. This was not to last, for in 1876, Randolph was implicated in a scandal involving the Royal Family. He had fallen out with the Prince of Wales, whom he threatened to expose as an adulterer. In those times, such behaviour from a public figure was completely unacceptable. He was marginalized by Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, being sent to work as viceroy in Dublin for the next four years.

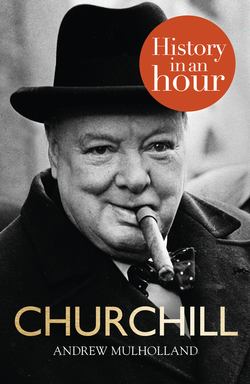

Seven years old – this photograph was taken in Dublin.

Dublin was the first home that Winston clearly remembered. It was there that he developed a strong attachment to Elizabeth Everest, the woman who served as his nanny and with whom he remained close throughout her life. When she lay dying in the summer of 1895, Churchill rushed to be by her side. Such ties were not uncommon for children of his background. It was normal for wealthy parents to employ a nanny to undertake most of their childcare. This, coupled with the somewhat distant attitude of Victorian parenting, meant that Winston gravitated towards those he spent the most time with. As well as Mrs Everest, there was his younger brother Jack, born in 1880.

Winston Churchill (right), with his mother and brother Jack, in 1889.

His mother was from a wealthy American business background. Jennie Jerome’s marriage to Randolph Churchill had been frowned upon by the English aristocracy, the Duke of Marlborough refusing to attend. She was rumoured to have Seneca Native American blood – something which was to fascinate Winston in later life, when he would often refer to his ‘Red Indian’ heritage. It was probably nonsense, but it made for a good anecdote.

In as far as the conventions of class and circumstance would permit, Jennie was warm and loving towards her eldest son. Yet he would soon be expected to attend boarding school. It was there that he missed the love of mother and nanny and grew distant from his father, as the latter became impatient with Winston’s chequered academic performance.

School

By now the Churchills had moved back to London, rehabilitated into the political elite. Randolph’s career was beginning to take off, as he became one of the most effective opponents of the Liberal government. Naturally, he expected great things of his eldest son. Winston’s first school was at Ascot, in Berkshire. This was a private ‘Preparatory’ school, from which the offspring of the wealthy were expected to move up to one of the country’s prestigious ‘Public’ schools – also private institutions, ‘public’ only in that they were open to those members of the public with sufficient means to pay their fees.

He did not take well to the rigid discipline. Homesick, but also rebellious and stubborn, Winston was moved shortly afterwards, on the ground of ill health. He fared little better at his second Prep school, although by now he was doing well in those subjects that genuinely interested him – chiefly History and English.

From 1888 he was accepted at Harrow, where although hardly an exemplary student, he did begin to mature and performed well in several areas. His love of all things military drew him to the school cadet force, and turned his mind to a career in the army. In fact, it was his father, who had noted Winston’s fascination with toy soldiers, who had suggested that the boy join the ‘Army Class’ – a special stream at the school for those aiming for a military career. Still disappointed in his son, Randolph also suspected that Winston was not clever enough for university.

He continued to enjoy the humanities and particularly writing, in which he was now beginning to show some flair. It was not nearly enough for his father, however. Their relationship was formal and frosty. Winston decided to apply for officer training at Sandhurst but faced a tough entrance examination. Finally securing a place at his third attempt, his father’s reaction was scathing rather than supportive. Yet in qualifying, Winston had shown considerable determination and application. Perhaps there was something more to this young man than his father was prepared to admit.

Sandhurst

It was at Sandhurst that Winston Churchill began to achieve a measure of success. The emphasis on military subjects, together with horsemanship, appealed. He also emerged as an opinionated young man, capable of influencing and leading those around him. While still at Sandhurst, he organized a colourful demonstration in support of the prostitutes in London’s theatres, who at the time were the victims of segregation and persecution. When he eventually ‘passed out’ from Sandhurst at the end of 1894, he was eighth in a class of 150. This would easily have earned him a place in one of Britain’s elite infantry regiments, but instead he elected to stick with his original choice, the cavalry. Before he could launch his career by joining the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars in January 1895, his father was dead.

The death of Randolph Churchill at 45 left a profound scar on Winston. Although Randolph had lived to see his son succeed at Sandhurst, the issues between them were unresolved. Randolph’s later years had been difficult. What may have been an undiagnosed brain tumour had gradually impaired his mental and oral faculties, to the extent that his final speeches in Parliament were embarrassing. Having combined the high offices of Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House in 1886, Randolph Churchill ended his career as a humble backbencher, laughed at and ineffectual. Winston concluded that the men died early in his family. From now on, he would throw everything he had at life. In this we see an early glimpse of his belief in ‘fate’ – that some things were simply meant to be. Already, he saw the army only as a stepping stone; for he was now considering a career both as a writer and as a politician in the House of Commons.