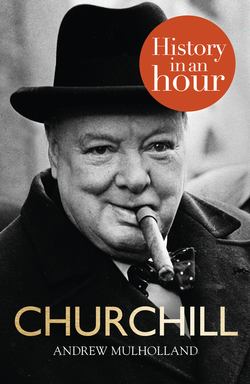

Читать книгу Churchill: History in an Hour - Andrew Mulholland - Страница 7

Young Radical: Early Political Career, 1899–1914

ОглавлениеAs so often in his life, Churchill would need to show considerable patience and skill in order to secure the first rung on the political ladder. Once established, however, he became one of the most precocious and well-known politicians of his generation. By the time the First World War began in 1914, Churchill would have commanded high office, crossed the floor of the House, won elections, lost them – and made as many enemies as friends.

Things did not begin well. In June 1899 he secured the Conservative Party nomination to fight a by-election in the constituency of Oldham, in the north of England. Public opinion was running in favour of the Liberal Party; he fought an awkward campaign, wrong-footing himself on religious issues. Churchill lost by a narrow margin. In October of that year the Second Boer War broke out in South Africa. Disillusioned with his early political efforts, he signed a contract with the Manchester Post to report on the conflict.

Back to War: South Africa

Once again Winston Churchill was off in search of adventure. Once again, too, he was to find it. Shortly after his arrival in Cape Town, Churchill travelled north towards the fighting. Boer guerrillas ambushed his train and, although now a civilian, Churchill organized a spirited defence of the encircled railway wagons. Superior numbers prevailed and he was taken prisoner, incarcerated in rough conditions in Pretoria. Undaunted, Churchill managed to escape from gaol and secrete himself on board a goods train, headed for Lorenço Marques in Portuguese East Africa. From there he made his way back to Cape Town and immediately attached himself to the forthcoming British military offensive. Unable to settle in the role of a civilian journalist, he teamed up with his cousin, the 9th Duke of Marlborough, and rode with the British cavalry.

Covering the Boer War for the Manchester Post, 1899.

All of this, of course, made great copy. He was even depicted as a ‘British General’ in a range of cigarette cards. In 1900 a general election was called and Churchill returned to England to re-fight the Oldham seat for the Conservatives. This time, on the back of widespread public recognition, he won. Finally, it seemed, Winston Churchill’s soldiering days were over. He would follow his father into the House of Commons; at last, he was a politician.

First political steps

Despite Churchill’s growing reputation as an author, he still found that it was difficult to make ends meet. Members of Parliament did not receive a salary at this time and so he was not alone in using the long parliamentary recess to secure further income. He went on a lecture tour, both in the USA and in Britain. On these occasions he would draw on his many adventures, relating these to the issues of the day. Churchill was not a natural, or particularly gifted, speaker. He also had a mild speech impediment, which did not help matters. As with many things in his life, his subsequent reputation for public speaking came through solid application. He worked at it – literally crafting every word and setting it out on paper before rising to speak. This apprenticeship in the lecture halls of the USA and during those early days in the House of Commons was eventually to stand him in good stead. For he encountered political opposition too, heckling and abuse – particularly in the USA, where the Boer War remained controversial.

His maiden speech in Parliament took place in February 1901, by which time he was already building a reputation as a troublemaker. Ironically, it poked fun at his future friend and colleague, David Lloyd George: ‘It might perhaps have been better, upon the whole, if the hon. Member, instead of making his speech without moving his Amendment, had moved his Amendment without making his speech.’ The barbed wit was a foretaste of things to come.

He was uncomfortable with the Conservative Party’s stance on free trade (the party favoured tariffs). On other issues he found himself to the left of the mainstream. He became associated with a group known as the ‘Hughligans’, after Hugh Cecil, their ringleader. Consequently, when Arthur Balfour formed a Conservative government in 1902, the troublesome Churchill had no chance of a ministerial position. He became increasingly embittered, finally resigning from the party to join the Liberal opposition in May 1904. Many in the Conservative Party would never forget what they saw as an act of betrayal.

Indeed it was as a Liberal, and as a radical one too, that Winston Churchill was to make his political name. In 1906 the country went to the polls, with Churchill standing as a Liberal in the previously Conservative seat of Manchester Northwest. He won, and was immediately appointed Under Secretary of State for the Colonies by Liberal Prime Minister Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman. He was now a government minister at the age of just 31.

It was during this period that Churchill became close to David Lloyd George, a fellow Liberal with high ambition and a reputation for radicalism. Lloyd George was twelve years older, thus becoming something of a paternal mentor to the young firebrand. When Churchill had actually crossed the floor of the House of Commons, he had gone straight to sit by Lloyd George’s side. They formed a powerful axis within the government, pulling it leftwards on questions such as minimum wages and social security. In 1908, Churchill authored The Untrodden Field in Politics, which articulated some of these views. He had kept up his other writing as well, having published a masterly biography of his father a few years earlier.

Climbing the ministerial ladder

As a junior minister, Churchill was learning his trade. For civil servants, he could be both infuriating and endearing. He was willing to listen and learn, respecting those in the Colonial Office who had greater knowledge and experience. On the other hand he meddled, involving himself in a wide range of issues, intervening in minor matters in a manner that might now be termed micro-management. His political superior, Lord Elgin, sat in the House of Lords and thus could not contribute to debate in the more politicized lower chamber. Churchill took his place, acting as government spokesman on weighty issues that would not normally be entrusted to such a junior minister. He became interested in security problems in the African and Asian colonies, consistently and effectively opposing the use of disproportionate force against tribal peoples.

Churchill’s personal life was transformed during the same period. Although infatuated with plenty of women, he was often gauche and ill at ease in their presence. His marriage proposals had been turned down twice, by different women, and this must have hurt. In 1908, though, he married Clementine Hozier, a woman with a similar background to his own with whom he was to form a remarkably successful partnership. Churchill was completely loyal to Clementine, although their disagreements could sometimes lead to shouting and thrown crockery. She was highly intelligent, with strident radical opinions with which she would often attempt to influence her politician husband. He was equally opinionated and stubborn – quite prepared to ignore his wife. They were to have five children, the first of whom, Diana, was born in July 1909. A son Randolph was to follow in 1911.

In 1908, Churchill was promoted to the Cabinet, still shy of his thirty-third birthday. Liberal Prime Minister Henry Asquith had made him President of the Board of Trade. It was here that his alliance with Lloyd George – they were already known as the ‘radical twins’ – was to have the strongest influence on government policy. Yet it very nearly didn’t happen. The convention whereby those appointed to Cabinet rank would seek re-election in their constituencies, led to the electorate of Manchester Northwest ejecting Winston Churchill from the House of Commons. With astonishing good fortune, he was invited to fight a by-election in the Scottish seat of Dundee. Within a month Churchill was back.

Alongside Lloyd George, Churchill pushed the Liberal Party towards labour market reforms designed to better the lot of the working man. These included minimum wages in some sectors of the economy, together with the first labour exchanges, tasked with tackling unemployment. Such measures were costly. As Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George was well placed to make the case for the requisite expenditure, but these were difficult times. Tensions arose between Lloyd George and Churchill. There was also a growing debate about naval rearmament, in the face of Germany’s expanding fleet. Lloyd George’s resulting 1909 ‘people’s budget’ provoked a constitutional crisis when the Conservative-dominated House of Lords refused to back it. Ultimately, matters were settled through the introduction of the 1911 Parliament Act – but once again, Churchill’s name was dirt within Conservative ranks.

Despite his fiery reputation, Churchill’s next ministerial appointment was to mark, at least in part, a shift to the right. After the general election of January 1910, he was made Home Secretary. It was one of the great offices of state.

Churchill’s brief tenure as Home Secretary coincided with considerable civil unrest, which fell within his remit. His response was to mark him down as an authoritarian and to demonize him among elements of the British left. There was violence during the 1910 Tonypandy riots in Wales and 1911 dock strike. In both instances, Churchill had authorized the use of troops. Yet in his defence, it seems he did so in order to exercise firm control from London, rather than risk the more amateurish efforts of the local authorities. At the same time he was agitating for a more lenient prison regime – another one of his responsibilities, earning him the sobriquet ‘the prisoner’s friend’. The picture of his domestic policy is therefore a mixed one.

Home Secretary Winston Churchill, highlighted, visits a police siege in Sidney Street, London, in 1911.

The Admiralty: Churchill becomes a ‘naval person’

In October 1911 he was moved again, this time to the Admiralty, as First Lord. In contrast to the First Sea Lord, the First Lord was the political head of the navy. In making this switch, Prime Minister Asquith recognized Churchill’s considerable military expertise. He had been a national hero during the Boer War and had taken a keen interest in military affairs ever since. During the Agadir crisis earlier that year, Asquith had been impressed with Churchill’s advice. War with Germany now seemed a distinct prospect. The Royal Navy, still the largest in the world, was complacent; Asquith had the remedy to hand.

At the Admiralty, Churchill largely bypassed the existing management. He brought back an ex-First Sea Lord, John ‘Jacky’ Fisher, as an informal adviser. Fisher’s ideas were as radical as his own. Together they worked hard to shake up conservative attitudes and modernize the fleet. It was their efforts which led to Britain’s early investment in naval air power, submarines, and the switch from coal to oil. They even tried to persuade the government to construct a tunnel under the Channel. Although this proposal was quickly turned down, they did strike a naval deal with France, which effectively locked the two countries together in strategic alliance. All of this was without a formal treaty. The modernization of the Royal Navy meant Britain would have reason to thank Churchill and Fisher when war with Germany came, only three years later.

The other political issue which preoccupied him during this period was Irish Home Rule. The proposal for a unified Irish parliament worried die-hard Unionist Protestants in the north of the country. Churchill urged compromise, but was well aware of the potential for bloodshed if matters got out of hand. Ultimately, the proposals for Home Rule were overtaken by broader events in Europe, as the Great Powers plunged into the First World War. Earlier in 1914, however, Churchill was implicated in controversy when he issued orders for British naval units to sail for Belfast. Again, Conservative politicians were furious. He was accused of seeking to provoke some kind of Unionist coup, so that sentiment in the north could be crushed by force of arms.

This seems unlikely. Churchill’s position was actually more nuanced. He disliked the fact that the Liberal government now needed to rely on the votes of Irish Nationalists at Westminster. In fact, he hoped Ireland could remain within the United Kingdom and he feared extremist views would jeopardize any settlement. Throughout his career, Churchill was a staunch defender of public order. He was also a bold and active minister. His Irish initiative with the fleet in 1914 may have been rash, but it probably amounts to little more than the product of such characteristics. Within ten years, however, problems in Ireland would again see him pilloried – this time with more justification, and from the other side.

As Europe slid into war in the summer of 1914, Churchill was regarded as Britain’s competent minister for the navy. He was a national figure, popular writer and contented family man, with two children and a third on the way. He relished the forthcoming struggle with Germany and took pride in the fact that the Royal Navy was now fully prepared.