Читать книгу Churchill: History in an Hour - Andrew Mulholland - Страница 6

The 4th Hussars: 1895–1899

ОглавлениеThe army was to provide a springboard for adventure and fame to the young Winston Churchill. Ultimately, though, he would quickly tire of it and seek broader vistas. For life as a second lieutenant in a British cavalry regiment would not be enough for one of his making.

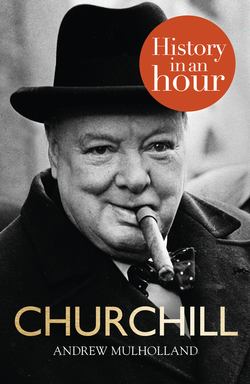

The young cavalry officer: the 4th Hussars, 1895.

He sought excitement, adventure and public attention; he also sought money. Although he enjoyed a generous allowance from his mother as well as his officer’s salary, Churchill concluded that these would not be sufficient to support his extravagant lifestyle. He therefore offered his services to the Daily Graphic as a war correspondent. This may seem odd for someone supposedly engaged full time in the army, but in those more relaxed days it was not difficult for a man of Churchill’s connections to secure leave of absence. He would travel to Cuba. For it was there that the Spanish government was attempting to suppress an armed revolt by nationalists fighting for independence.

Churchill went with his friend Reginald Barnes and on his way he visited the USA for the first time. He stayed in New York, with a friend of his mother’s. This was Bourke Cockran, a prominent Democrat member of the House of Representatives. If Churchill’s notion of becoming a politician was hazy on his arrival in New York, by the time he left it had become a fixed ambition. Cockran’s fiery rhetoric, political connections and dinner-table discussions enthused the young journalist.

He was also enthused and fascinated by war. For Churchill, it was the ultimate expression of the competition between nations, but also a romantic adventure. His early exposure to its realities, however, was to temper such notions and imbue him with a strong sense of compassion for those who suffered its consequences. In Cuba he was shot at for the first time, on his twenty-first birthday. He found the Cuban rebels amateurish, but had little respect either for the Spanish army or its conduct. Overall, he seems to have enjoyed himself: writing colourful despatches for the Graphic, and developing a lifelong passion for Cuban cigars.

India

Back in England he was dismayed to be posted to Bangalore, India, with the rest of his regiment. India held little appeal for him, primarily as he saw it as a backwater. Once there, he spent much of his time devouring the British press, following the issues back home with more interest than he did those on the Subcontinent. Nonetheless, the army was there for a purpose and Churchill determined to involve himself in military action wherever he could. On learning of an expedition against rebellious Pashtun tribesmen on the Northwest Frontier, Churchill pestered his superiors for an attachment to the force. He finally got his way, and also a contract to write about it for London’s Daily Telegraph.

The experiences were to form the basis of Churchill’s first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force, which he was to publish in 1898. War on the frontier was tough. Churchill saw a friend cut down in front of him and had to be given a direct order to leave his stricken comrade as the rest of the regiment retreated. He wrote about the blanket-wrapped corpses who, only hours before, had been proud soldiers of the Queen-Empress. Brave as well as compassionate, Churchill was now an experienced and capable cavalry officer.

It was intellectual training, though, which was to prove the more important achievement of his time in India. Despite the excitement of the frontier war, Churchill actually spent most of his days at the barracks in Bangalore. He was acutely aware that he had not been to university, and that this might be held against his ambitions for high office. He was also anxious to develop and improve his written style. With the encouragement of his mother, he set about a systematic programme of self-education which was to remedy these shortcomings. Once again, Churchill was to show determination and self-discipline. As with many challenges in his life, his approach may not have been conventional, but he was ultimately successful. Lady Randolph would send bundles of books to her son, and he would set aside several hours every day in order to read them. He read the Classics, history and philosophy. He quite deliberately modelled his writing style on those of Gibbon and Macaulay, possibly Britain’s greatest nineteenth-century historians and, certainly, masters of the written word. Like Abraham Lincoln before him, Churchill was largely self-taught; and also like Lincoln, he was to become one of the most widely read and highly educated leaders of his age.

His personal views were inevitably shaped by this enterprise. To his emerging imperialism and nationalism can be added a fascination with what he would call ‘destiny’. Churchill was a strong believer in his own providence and the idea that some things were ‘meant to be’. At the same time, he was angry and dismissive of much religious doctrine and practice, which he found rigid and exploitative. In some senses a spiritual man, Churchill would remain a notional Christian. Yet it was during this period that he became noted for his challenging views on formalized religion. He also took to writing fiction – writing his only novel, Savrola, in India.

The Sudan

In North Africa, meanwhile, the British Empire faced another challenge, in the form of the Mahdist movement in the Sudan. Having seen the Mahdists wipe out a British force at Khartoum in 1885, by 1898 General Herbert Kitchener was leading a punitive expedition down the Nile from Egypt. Once again, Churchill successfully lobbied to be sent along as a soldier-journalist. This time his sponsor was the Morning Post newspaper. He was attached to the 21st Lancers, the regiment which was to undertake Britain’s last major cavalry charge. At the close-fought Battle of Omdurman on 2 September 1898, Churchill was among their ranks as they surged forward to clear a route through to the city of Khartoum. The 400 troopers were surprised by over 2,000 concealed infantry, and the ensuing melee was extremely violent. Churchill was disgusted at the barbarism displayed by his own side, as surrendering enemies were skewered by the lancers. He was to record this, as well as scathing criticism of Kitchener, in a two-volume account published as The River War.

Returning to Britain, Churchill felt the need to move on. The routine life of a regimental officer was not for him – he had, after all, spent relatively little time serving with the regiment of which he was supposedly a member. He was by now a well-known writer, with a burgeoning new income stream. He had for some time cultivated contacts within the Conservative Party, making his first political speech as early as 1897. In spring 1899, Churchill resigned from the British Army. It was time to make the leap into politics.