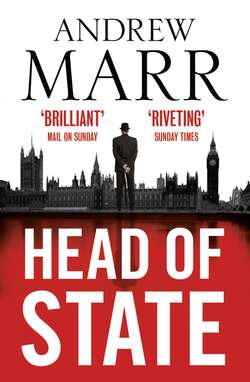

Читать книгу Head of State: The Bestselling Brexit Thriller - Andrew Marr, Andrew Marr - Страница 14

How History is Made

ОглавлениеAt the moment that Ken Cooper stepped into the lift, Lord Trevor Briskett and his research assistant Ned Parminter were squashed together in a commuter train from Oxford. They were both scanning that morning’s Courier. Lord Briskett read the paper from the middle outwards, starting with the editorial and the commentators, then checking the business and political news, before idly skimming the home pages, which were mostly filled with things he’d heard already on last night’s news or the 7 a.m. bulletin on the Today programme. One celebrity was in favour of decluttering. Another was less sure. The girlfriend of somebody on a television show had drunk too much in a club. The age of newspapers, he reflected, was coming, whimpering, to an end.

Ned Parminter was brushing through the iPad edition of the paper with his forefinger, flicking the screen at great speed. The Courier at least still covered politics with some vigour, although the news pages seemed to be in favour of Britain leaving the EU, while the comment pages were aggressively the other way.

Neither of them paused to read the short report on the headless Battersea corpse. Corpses, particularly headless ones, were clearly something to do with the criminal underworld, and were therefore politically unimportant. Briskett and Parminter were following a bigger story than that. ‘Vote clever.’ ‘Vote for freedom.’ A nation torn in two.

Dressed in his trademark coarse green tweeds, with his halo of frizzy white hair and heavy horn-rimmed spectacles, part A.J.P. Taylor, part Bamber Gascoigne, Trevor Briskett was famous enough from his TV performances to attract second glances from his fellow commuters. On the streets of Oxford – that crowded, clucking duckpond of vanity and ruffled feathers – he was stopped-in-the-street famous.

And rightly so. For Briskett was the finest political historian of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. His early biographies – Blair, Thatcher, Johnson – were still in print, while the memoirs of scores of almost-forgotten politicians had long since vanished to charity shops and recycling dumps after selling only a few score copies. Briskett’s account of the modern constitution had been compared to the works of that Victorian master-journalist Walter Bagehot. His history of British intelligence during the Cold War had been praised by all the right people. Emeritus professor at Wadham, winner of numerous literary prizes, elevated five years ago to the Lords as a crossbencher after chairing a royal commission on security lapses at the Ministry of Defence, Briskett was regularly tipped to be the next member of the Order of Merit.

Yet somehow these decorative embellishments, which might have weighed him down and made him soft, slow and comfortable, had had little apparent effect on Trevor Briskett. At seventy he was as sharp, as boyishly enthusiastic, as wicked a gossip with as rasping a laugh, as he had been at thirty. The exact nature of the pornography discovered on the minister’s lost laptop. The attempt to blackmail a senior minister over his wife’s cocaine habit. Just who Olivia Kite was taking to her bed these days … If you really wanted to know, you went to Briskett, and he would tap his nose, lean towards you, give a wolfish smile and a ‘dear boy’, and spill all the beans.

Thus, it had generally been admired as a rather brave decision when the prime minister announced that he had appointed Briskett as the official historian of the great European referendum. The PM, himself an amateur political historian, had argued that such was the momentous nature of the choice now before the British people that they were owed – the nation was owed – a proper, in-depth account by a proper writer. Briskett, he had promised, would be given unparalleled access to the members of his inner team for the duration of the campaign. He would be welcomed at Downing Street, he would be given copies of the emails, the strategy documents – everything. And after it was all over, people might actually read his book.

No sooner had the PM announced this than Olivia Kite, on behalf of the get-outers, issued a press release declaring that she too admired Lord Briskett, whom she regarded as an authoritative and independent voice, and that she would give him the same level of access to her team.

The political commentators said that the PM’s decision to give contemporary history what Briskett had called ‘the ultimate ringside seat’ was evidence of his great confidence about the outcome of the referendum. His evident conviction that he would win, and that victory would be the ultimate vindication of his premiership, was itself damaging to his opponents. Olivia Kite had had little option but to make Briskett as welcome in Prince Rupert’s tent as in Cromwell’s.

Basking in this hot limelight, Briskett moved lightly. He wanted to do all the work himself, so far as he could. He had brought in only his protégé Ned Parminter, a shy but brilliant PhD student who, Briskett thought, might one day be a significant contemporary historian himself.

Parminter, with his wiry black beard and intense dark eyes, looked like an Orthodox priest in civilian clothes. Although he shared Briskett’s urbane sense of humour, his romantic English patriotism had a fanatical streak.

Together, the two of them made up a balanced ticket: Briskett’s delight in Westminster gamesmanship inclined him towards the larger-than-life, principled yet unscrupulous figure of the prime minister. Parminter, a specialist in the seventeenth-century development of Parliament, was a natural Olivia Kite supporter. They had, of course, never discussed their allegiances on this matter between themselves.

Now the two of them were on their way to meet the prime minister himself. As the train wriggled through West London towards Paddington, Briskett leaned forward in his seat.

‘You’re seeing that … girl, Ned, after our rendezvous?’

Parminter scratched his beard under his chin, a sign of anxiety, before slowly replying. ‘She’s invaluable. She’s across everything in the Kite campaign. She reads all the emails, all Kite’s texts, on her official BlackBerry and her personal one. She’s copying us into every piece of traffic.’

‘And does the ever-lovely Mrs Kite know this?’

‘Apparently. I think she must. Jen’s nothing if not loyal, so I guess Kite’s fine with it.’

‘Good girl. Good for you, too.’

‘There is one other thing. It’s a bit odd. She also seems to know rather a lot about what’s happening on the other side. Far more than she ought to. Hidden channels in Number 10, perhaps.’

Briskett rubbed his hands with pleasure.

‘Really? Sleeping with the enemy, is she? Delicious. At a moment like this, what is happening in each HQ is our primary concern. Let us wallow, Ned, in the panics, the little feuds, the unwarranted pessimism and the foolish overconfidence. But in a sense, what matters most is what is harder to discover. I mean, what is happening between the camps. It’s there that the deepest secrets lie. And what is this fascinating creature’s full name, Ned?’

‘Jennifer Lewis. But she prefers Jen. I’ve known her since uni.’

Briskett exhaled an irritated hiss.

‘You mean you’ve known her since you were up at Oxford, Ned. I really cannot understand this squirming self-abasement about “uni”. It would be a different matter if it were Keele, but I assume – given her youth and prominence – that she was at Oxford too. Or, poor girl, Cambridge?’

‘Somerville.’

‘Hmm. PPE?’

‘PPE.’

‘Well …’

The two men lapsed into silence until the train was almost at Paddington.