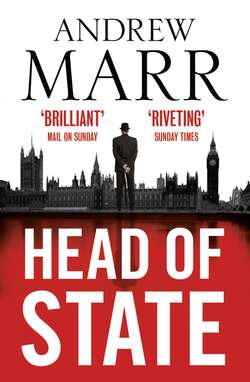

Читать книгу Head of State: The Bestselling Brexit Thriller - Andrew Marr, Andrew Marr - Страница 18

Mothers and Daughters

ОглавлениеOn the face of it – and hers was an ivory, oval face, offset by a sensual, challenging mouth – Jennifer Lewis’s background could hardly have been more different. She had been brought up by a strict aunt in an old Devon rectory, and had attended the Royal Girls’ Academy outside Exeter. There she had appeared gloriously normal. But Jennifer’s cross, the painful burden chafing her slim shoulders, had always been her mother. Myfanwy Davies-Jones, a Welsh poetess and novelist with a cloud of yellow hair and a scarlet reputation, had arrived in the King’s Road in July 1963, not quite straight from her pit-village school, and had thrown herself headfirst into West London society during the most exhilarating and self-indulgent years those dirty terraced streets and dusty parks had enjoyed since the Second World War.

She attracted the rich and the dangerous – men such as Lord Croaker, the asset-stripper and zoo-owner; and the right-wing journalist and politician Sir Rufus Panzer. Way back, Panzer had been a communist, even volunteering as a machine-gunner in a red corps during the Spanish Civil War. In his sixties he had been a lean and extreme supporter of the rising Tory right, though he was later rejected by Margaret Thatcher: ‘Brilliant man, but a little too much gleam in the eye.’

After half a dozen relationships with such wild characters, diluted by the occasional artiste, Myfanwy’s first novel was acclaimed as the satirical roman à clef swinging London had been waiting for. Sidetracked from her new celebrity by a doe-eyed performance poet from Liverpool, she gave birth to a son, quickly palmed off to a couple who for some reason wished to adopt him. She would have preferred an abortion, she frankly admitted to her friends, but had been too disorganised, lazy, and perhaps frightened, to go through with it.

The hospital long remembered Myfanwy Lewis – for this episode she had chosen to revert temporarily to her real name, rather than the one by which she was known to her public. Its nurses had never before had to deal with a strong aroma of marijuana smoke in the maternity wing, let alone a constant stream of arguing and backslapping visitors in leather jackets and kaftans who stayed late into the night playing Joan Baez songs. Myfanwy had treated the birth pains and what they brought forth as a baffling surprise, unpleasant enough at the time, but soon afterwards useful material for one of her most successful books.

Then, many years later, when Myfanwy was on the very brink of the menopause, she had swanned back to the hospital, still striking, still attended by adoring young men, hugely pregnant and hugely irritated at this second unexpected turn of events. Thus arrived the small and cross Zuleika Maria-Guadeloupe Attracta Gonne Lewis.

In later years, the unwanted Jen – as she preferred to be called – had never thrown her mother’s evident lack of interest, or even maternal instinct, back at her. It would have been as futile as complaining to a bird about its song. As a baby, as a toddler, and as a striking, solemn-faced young girl, she had been passed from friend to relative to acquaintance. ‘Who’s on Jenny Wren duty tonight?’ literary editors would ask publishers’ secretaries. Jen remembered only a haze of kindly, feckless faces, wooden floors and Turkish carpets in colourfully furnished flats and houses across West London. From time to time Mother would appear briefly, brandish her like a prize at a party or barbecue, then disappear again, after flinging her a bouquet of incomprehensibly flowery language and a warm, nauseatingly perfumed farewell embrace. Jen still recalled the moist, sickly, lipsticked mouth and the wet, lolling tongue, imbued with tobacco and wine, with a shudder.

In many other families, both Jen and her mother would have got over all this, and thrived. Jen would have turned her early years into a funny late-night story for the benefit of boyfriends, and become increasingly admiring of her mother’s genuine, exotic literary gift, and even her famous face, like that of a fine-boned elf in a wig, which had popped up so often, sketched or photographed, on the covers of extinct magazines and Sunday Times colour supplements. Myfanwy, meanwhile, would have come to appreciate her daughter’s precocious intelligence and her looks, which echoed her own, and woven her childish triumphs, pearls of wisdom and delightful mistakes into brittle newspaper columns. Eventually, the two would have become friends.

It never happened like that. Jennifer was, at least, spared those newspaper columns. She had the wrong temperament to understand her mother. Temperament is fate, and Jen was temperamentally literal rather than literary, almost male in her self-absorbed preference for order and systems. She hated sloppiness, and the slopping around of personal secrets. And when she eventually read her mother’s novels – Seven Sermons for Secular Sinners, or Leprosy and the Ladies’ Room – she found them emotionally incontinent, plotless and frankly embarrassing. Myfanwy’s love affairs, described with an earthy, sensuous detail that in those days was very rare from a woman, had made her rich. First editions of her early books now changed hands for thousands of pounds, while the paperbacks could be found, squeezed between Jackie Collins and Margaret Drabble, on bookshelves across North London. To her daughter, this literary celebrity was incomprehensible.

Jen’s life only began to make sense to herself when, aged eleven, she was dispatched from London to go and live with her mother’s sister, a stern, quietly religious woman married to a dentist in Devon. Hundreds of miles away from the nearest literary party, she enjoyed the clipped lawn and the piano lessons in a large, oak-timbered room that smelled of old fires and damp Victorian sofas. She loved her school, the biology and chemistry lessons in particular, and made a group of friends, quiet, serious girls like herself. She collected stamps, butterflies and even football cards. For days – even weeks – at a time she felt herself happy.

Oxford was another fresh start, a place of wonders. A natural scientist, in both senses, Jenny found herself being pulled towards politics during the short-lived Johnson administration. Repelled by the beery and yobbish advances of young men who proclaimed themselves socialists, or even revolutionaries – and not simply because her political heroine Margaret Thatcher had herself been a scientist – she joined the Conservative Party. Jen believed in reason and efficiency. She didn’t much care about the European Union one way or the other – that would come later. Her politics did not make her universally popular. But, confronted by the self-righteous arguments of the college lefties, she prided herself on never losing her temper, and on hitting back with carefully memorised figures and quotations. She was quickly spotted.

In her second year Jen switched from ‘nat sci’ to PPE, and became an active Tory student, elbowing aside moist-palmed, stammering young men as she rose through the ranks of the Union, until in her final year she was elected its president. Nothing could have mortified her mother more. In college she was known universally as ‘June’, which she had assumed was the result of a mishearing, until one evening in the student bar she overheard a girl explaining to her friend, ‘No, not Jen. June – cold and bright.’ When her mother, a regular in the letters pages of the Observer and a prominent campaigner for the arts, came to speak at the Union, Jen did not attend. By then she had led the winning side in many Union debates herself.

So it came about that after university the girl who had assumed that she would spend her adult life as a laboratory assistant or a research scientist went instead to work at Conservative Central Office. In that boys’ world she was recognised as brilliant but difficult. She had spent a happy year working for the man – now much heavier and with silver through his wiry hair – who would become prime minister. But a disastrous love affair with a young, married MP who managed to keep his seat despite his exposure in the press, ended in her leaving that job both sadder and wiser.

It was then that she was snapped up by Olivia Kite, who recognised her brilliance and made her the number-cruncher and analyst-in-chief for the increasingly powerful Eurosceptic group inside the parliamentary party. Slim, pale, and with her mother’s shining hair, Jennifer Lewis continued to be much admired – though mostly from a distance.