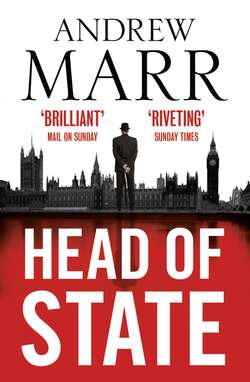

Читать книгу Head of State: The Bestselling Brexit Thriller - Andrew Marr, Andrew Marr - Страница 17

Fathers and Sons

ОглавлениеTwo nights previously, Lucien McBryde had been walking slowly up St James’s Street, deep in thought. (Not deep enough: this was his last weekend alive, although he wasn’t aware of that fact. Had he known, he would more consciously have drunk in the salmon-coloured light on the sides of the buildings, the indistinct urban scent of late summer, the kestrel hovering over St James’s Palace.)

Samuel Johnson held that to live a good life meant acting morally as if you were about to die, while conducting your daily business as if you were going to live for another fifty years. Lucien McBryde failed on both counts.

Morally, his main failings were idleness and irresponsibility mitigated by charm, an addiction to a stimulating powder, and another to stimulating, strong women. In his defence, he would point out that while many men regarded them simply as complicated and expensive instruments for their own pleasure, he was a genuine admirer of women – their smells and tastes, the way they walked and the way they talked – and that they tended to sense this. ‘I am essentially a male lesbian,’ he would declare.

In his professional life, McBryde acted as if he had an endless, charmed life, with unlimited possibilities for second chances and eleventh-hour renegotiations. His tax returns, bills, investments, pension and passwords were in an entirely chaotic state. For the best part of a decade Lucien McBryde had lived blissfully from day to day. But his supply of rising suns and golden sunsets was about to run out.

Tonight, McBryde had a nagging toothache. Eventually his tongue located it. Pain sought pain. Probing the back of his palate, he thought back to the events of two months before, when his father had died and his own life had begun to spin out of control.

Old Robson McBryde, Lucien’s widowed father, had been a hard man to love. In Lucien’s case, this was perhaps partly because they were closer to two generations apart in age than one. But it was mainly because his father was an impossible man to live up to. With a face like an American bald eagle, hacked and fissured by many decades of concentration and humour, Robson McBryde was a legend in Fleet Street and beyond – the wartime hero who pursued a career as a foreign correspondent in the Middle East, reporting on the first Gaza camps for the Guardian with a ferocity which led (thanks to a quiet word from a major advertiser to the paper’s impeccably liberal editor of the day) to his summary dismissal on the unspoken charge of anti-Semitism.

Robson migrated to other newspapers as a pitiless moralist in the foreign affairs field, churning out endless lucid and fact-packed columns on the immorality of British foreign policy across the Middle East and beyond. As early as the Suez debates of 1956 he was cited in the House of Commons as an authority, and regarded as the then prime minister’s personal nemesis in the press.

Lucien had grown up in the menacing shadow of his father’s moral certainties. It had been a boyhood of newspapers flattened out on the breakfast table and fingers stabbed down angrily in emphasis, of after-school harangues and sad shakings of the head over his lack of interest in current affairs and, more generally, his academic performance. Old Robson, a liberal and Fabian of the old school, would never have raised his hand against a child, yet in his perpetual disappointment, punctuated by occasional door-slamming tantrums, the old man proved a brutally destructive humanitarian, a Guardian-reading human-hater. His son, lying on the floor with his chess set or watching television, had dreamed of being taken in and adopted by the parents of his best friend Jonathan. They were kindly people, of no known opinions.

The father had never regarded the son as his intellectual equal. Lucien’s attempts to impress him, whether through his school essays or in conversation, tended to result only in hard-eyed silences or sarcastic rejoinders. (‘Ha! Islington’s home-grown Mencken has, I think, mistaken Ernie for Nye’; or, ‘Young Woodward, I presume? Iran and Persia are the same fucking place.’) It is surprisingly easy to destroy a young man’s sense of himself.

When Lucien finally got a job after university as a gossip reporter for a midmarket newspaper, he did not even try to persuade his father that this was a respectable way of earning a living. The old man nourished his disappointment for years, missing no opportunity of praising his son’s award-winning contemporaries, and asking awkward questions about the sources of his minor scoops.

Early on in his career, Robson had given a leg-up to Ken Cooper, now the editor of the National Courier, and they had remained drinking friends ever since, having lunch together every few months. Once they had been three, but the intense, wiry-haired young politician who had been such brilliant company, and who had kept them gasping and spluttering with laughter for years, had drifted away, too busy and too ambitious for alcoholic afternoons. Having kept his head down during the Blair, Brown and Cameron years, neither journalist was surprised when he rose, comparatively late in life, to become party leader and then prime minister.

With Ken and Robson left by themselves, their lunches became almost silent affairs, but somehow they survived Ken’s continued success in the glittery, shallow, modern newspaper world. From opposite ends of the political spectrum, the two friends had agreed an armistice in which the only fit subject of conversation was the catastrophic decline of the country. Their habitual game was to try to identify fresh signs of this, and to probe their origins.

After twenty minutes of gloomy silence, Ken would say, ‘Inappropriate.’

With any luck, Robson would show sufficient interest for Ken to continue.

‘Our forefathers talked about human evil. You and I … well, we’d say that something – I don’t know, child abuse, or trying to strangle your wife in public – was wicked. These days, it’s just fucking inappropriate. That’s the worst fucking word they’ve got.’ (They was code for everyone under fifty.)

Robson would continue to slurp his soup, and Ken to smash his salad to pieces. Eventually one of them would say, ‘Butchers.’

And so it would go on. Sometimes a gambit wouldn’t work. ‘Velcro. Bloody Velcro,’ Robson might say, but Ken would only look up blankly and shrug. Another thirty minutes or so of friendly, despairing silence was then guaranteed.

On only one subject would Robson frown and show displeasure.

‘That boy of yours isn’t completely stupid, you know,’ Ken might say. ‘Brought in a decent little story last week …’

Lucien had been hired by the Courier’s deputy editor, but Robson refused to believe it wasn’t patronage, and never forgave Ken for his supposed weakness.

But Ken was right: Lucien McBryde really wasn’t completely stupid. And so he had fluttered, broken-winged, from perch to perch, eventually making enough money at the Courier to be able to enjoy himself, and to dress well, while never hanging on to it long enough to own property, or any of the other appurtenances of serious, grown-up life.

Lucien was not on the run from his father. That level of exertion would have appalled him. He was, rather, on a gentle jog from adult responsibility, and as he continued up St James’s Street he flattered himself that, in that respect at least, he had been doing rather well. But then he had tripped over Jen Lewis, and had fallen, hurtling head-down, parachute-free, in love.