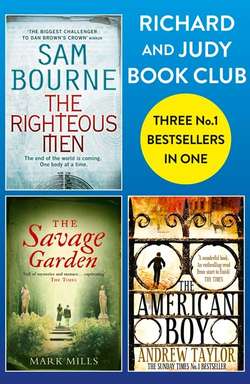

Читать книгу Richard and Judy Bookclub - 3 Bestsellers in 1: The American Boy, The Savage Garden, The Righteous Men - Andrew Taylor, Andrew Taylor - Страница 19

Chapter 9

ОглавлениеI watched Charlie Frant in morning school, both before breakfast and after it. The boy sat by himself at the back of the room. I doubted if he turned a page of his book or even saw what was written on the one in front of him. His coat was now too bedraggled to have a military air. He had tear tracks on his cheeks, and his nostrils were caked with blood and mucus. Smears on the sleeve showed where he had wiped his nose.

At breakfast, I told Dansey what had happened in the night. The older man shrugged.

“If the boy goes to Westminster School, he’ll get far worse than that.”

“But we cannot let it pass.”

“We cannot prevent it.”

“If the older boys would but exert some authority over the younger ones –”

Dansey shook his head. “This is not a public school. We do not have a tradition of self-governance by the boys.”

“If I went to Mr Bransby, might he not expel them or at least discipline them – Quird and Morley, I mean?”

“You forget, my dear Shield: the true aim of this establishment is not an educational one. Considered properly, it is nothing but a machine for making money. That is why Mr Bransby has sunk his capital in it. That is why you and I are sitting here drinking weak coffee at Mr Bransby’s expense. Both Quird and Morley have younger brothers.” Dansey’s lips twisted into their Janus-like frowning smile. “Their fathers pay their bills.”

“Then is there nothing to be done?”

“You can beat the wretched boys so soundly that you reduce their ability to persecute their unfortunate friend. At least I can be of assistance in that respect.”

At eleven o’clock, after the second session of morning school, I flogged Morley and Quird harder than I had ever flogged a boy before. They did not enjoy it but they did not complain. Custom blunts even pain.

Later, I caught sight of Charlie Frant in the playground. Half a dozen boys had grouped around him in a ragged circle. They tossed the hat from one to the other, encouraging him to make ineffectual grabs for it. The hat had lost its tassel. Some wag had contrived to pin it on the back of the olive-green coat.

“Donkey,” they chanted. “Who’s a little donkey? Bray, bray, bray.”

When lessons resumed after dinner, Frant was not at his desk. He had hidden himself away to lick his wounds. I decided that if Lord Nelson could turn a blind eye to matters he did not wish to see, then so could I. I did not, however, turn a blind eye to either Quird or Morley. Their work, never distinguished, withered under the unremitting attention that I bestowed upon it. I gave them both the imposition of copying out ten pages of the geography textbook by the following morning.

Towards the end of afternoon school, the manservant came from Mr Bransby’s part of the house and desired Dansey and myself to wait upon his master without delay. We found him in his study, pacing up and down behind his desk, his face dark with rage and a trail of spilt snuff cascading down his waistcoat.

“Here’s a fine to-do,” he began without any preamble, before I had even closed the door. “That wretched boy Frant.”

“He has absconded?” Dansey said.

Bransby snorted.

“Not worse, I hope?” There was the barest trace of amusement in Dansey’s voice, like an intellectual whisper pitched too low for Mr Bransby’s range of comprehension. “He has – harmed himself?”

Bransby shook his head. “It appears that he strolled away, as cool as a cucumber, after the boys’ dinner. He walked a little way and then found a carrier willing to give him a ride to Holborn. I understand that Mrs Frant is away from home but the servants at once sent word to Mr Frant.” He waved a letter as though trying to swat a fly. “His stable boy brought this.”

He took another turn in silence up and down the room. We watched him warily.

“It is most vexing,” he continued at length, glowering at each of us in turn. “That it should concern Mr Frant – the very man we should study to please in every particular.”

“Has he settled on withdrawing the boy?” Dansey asked.

“We are spared that, at least. Mr Frant wishes his son to return to us. But he demands that the boy be suitably chastised for his transgression so that he apprehends that the discipline of the school is firmly allied to paternal authority. Mr Frant desires me to send an under-master to collect his son, and he proposes that the under-master should flog the boy in his, that is to say Mr Frant’s, presence and in the boy’s own home. He suggests that in this way the boy will realise that he has no choice but to knuckle down to the discipline of the school and that by this he will learn a valuable lesson that will stand him in good stead in his later life.” Bransby’s heavy-lidded eyes swung towards me. “No doubt you were about to volunteer, Shield. Indeed, my choice would have fallen on you in any case. You are a younger man than Mr Dansey, and therefore have the stronger right arm. There is also the fact that I can spare you more easily than I can Mr Dansey.”

“Sir,” I began, “is not such a course –?”

Dansey, standing behind me and to the left, stabbed his finger into my back. “Such a course of action is indeed a trifle unusual,” he interrupted smoothly, “but in the circumstances I have no doubt that it will prove efficacious. Mr Frant’s paternal concern is laudable.”

Bransby nodded. “Quite so.” He glanced at me. “The stable boy has ridden back to town with my answer. The chaise from the inn will be here in about half an hour. Be so good as to discuss with Mr Dansey how he should best discharge your evening duties as well as his own.”

“When will it be convenient for me to wait upon Mr Frant?”

“As soon as possible. You will find him now at Russell-square.”

A moment later, Dansey and I went through the door from the private part of the house to the school. A crowd of inky boys scattered as though we had the plague.

“Did you ever hear of anything so unfeeling?” I burst out, keeping my voice low for fear of eavesdroppers. “It is barbaric.”

“Are you alluding to the behaviour of Mr Frant or the behaviour of Mr Bransby?”

“I – I meant Mr Frant. He wishes to make a spectacle of his own son.”

“He is entirely within his rights to do so, is he not? You would not dispute a father’s right to exercise authority over his child, I take it? Whether directly or in a delegated form is surely immaterial.”

“Of course not. By the by, I must thank you for your timely interruption. I own I was becoming a little heated.”

“Mr Frant and his bank could purchase this entire establishment many times over,” Dansey observed. “And purchase Mr Quird and Mr Morley as well, for that matter. Mr Frant is a fashionable man, too, who moves in the best circles. If it is at all possible, Mr Bransby will do all in his power to indulge him. It is not to be wondered at.”

“But it is hardly just. It is the boy’s tormentors who deserve chastisement.”

“There is little point in railing against circumstances one cannot change. And remember that, by acting as Mr Bransby’s agent in this, you may to some degree be able to palliate the severity of the punishment.”

We stopped at the foot of the stairs, Dansey about to go about his duties, I to fetch my hat, gloves and stick from my room. For a moment we looked at each other. Men are strange animals, myself included, riddled with inconsistencies. Now, in that moment at the foot of the stairs, the silence became almost oppressive with the weight of things unsaid. Then Dansey nodded, I bowed, and we went our separate ways.