Читать книгу Reacher Said Nothing - Andy Martin - Страница 13

2 CHAPTER ONE

ОглавлениеWhich is when I blew into town. To watch it happen. To bear witness to Lee Child writing the next instalment of Jack Reacher’s continuing adventures. I first picked up a Reacher, purely by chance, in a little bookstore in Pasadena, down the road from Caltech. I knew exactly how Malcolm Gladwell felt when he plotted his incremental curve of addiction: you start out reading Lee Child in paperback; then you realize you can’t wait that long and start buying his books in hardcover; your next step is to call around your publishing friends and ask them to send you the galleys. Ultimately, he reckoned, you would have no option but to ‘break into Lee Child’s house and watch over his shoulder while he types’.

I had read all the books. I’d reviewed a few of them. I’d interviewed the guy. Twice (once in the UK, again in the US). Now I was finally breaking in. I had to know what happened next. Before it happened. I was doing what Gladwell had only dreamed of.

There was a date Lee couldn’t miss.

September 1, 2014. Labor Day in the US. A public holiday. But not for Reacher. It was twenty years to the day since, on the verge of leaving his job with Granada Television, Lee, nearly forty years old, had gone out and bought the paper to start writing Killing Floor, the first of the series. And a pencil (he still had the pencil, much reduced in size). Every year, ever since then, he’d started a new one on the very same day. It was a ritual with him. One he couldn’t mess with.

Lee didn’t have to become a writer. He had a couple of options after he dropped (or was pushed) out of television. After being fired, he had taken the trouble to go along to his local employment exchange, as it was then known. More like an unemployment exchange. This was the height – or depth – of the post-Thatcher golden age in the north of England. Manufacturing jobs were being slashed – not that he would necessarily have got one even if they had been numerous. There was only one job going that he was really qualified for: warehouseman. He had given it some serious consideration. Then he had gone out to buy the paper. ‘We were only just making enough to get by. Then I lost my job. It was fairly desperate.’

He wrote the first chapter. Killing Floor, chapter one. Then showed it to his wife. Everything depended on what she said. He could keep on with chapter two. Or he could go and apply for the warehouseman job. She read what he had written and then put it down.

‘What do you think? Shall I keep going?’

‘Keep going,’ she said.

He went back to work. The choice had been made. Maybe he would never have made a decent warehouseman anyway.

At seven-thirty that morning, September 1, we got in the car to drive to the TV studio. CBS This Morning. With Lee Child. There were more people in the car – Lee and his publicist and his editor and his assistant and one or two others (his crew) and me – than on the streets outside. ‘Everyone else is on holiday and we’re working,’ his apartment doorman had said. As we glided through empty streets, New York on Labor Day reminded me of Lee’s description of a backwoods smallville in Montana:

There were no people on the sidewalks. No vehicle noise, no activity, no nothing. The place was a ghost. It looked like an abandoned cowboy town from the Old West.

‘Today we begin!’ said Lee, like a kid going to a birthday party, not thinking about the TV interview at all. ‘I want to get ahead this time, take the pressure off.’

‘Do you have it in the diary?’ I said.

‘No, that would be too obvious,’ he said. ‘But it is in my head. I can remember it like it was yesterday. Twenty years ago. It was a Thursday. Around one fifteen. My lunch break, because I was still working even though I knew it was nearly over. W. H. Smith in the Arndale Centre, in Manchester – the one that got bombed by the IRA. I was working all weekend. Then I started writing on the Monday. I had no real time off at all.’

‘So it has to be today.’

‘I need ritual. My life needs a shape. It doesn’t matter that I’m doing interviews, I have to start today.’

‘That was a great opening [to Killing Floor],’ I said. ‘I was arrested in Eno’s diner. At twelve o’clock. I was eating eggs and drinking coffee.’ ‘The first day is always the best,’ Lee said. ‘Because you haven’t screwed anything up yet. It’s a gorgeous feeling. I try to put it off as long as possible because when it’s gone it’s gone.’

‘Do you have any kind of strategy for writing, or rules or whatever?’

‘I only really have one. You should write the fast stuff slow and the slow stuff fast. I picked that up from TV. Think about how they shoot breaking waves – it’s always in slow motion. Same thing. You can spend pages on pulling the trigger.’

‘Die Trying. All the mechanics and chemistry of firing a shot. Like calculus.’

‘And what happens to the bullet afterwards. That’s the thing most writers forget – they think it’s just pull the trigger and wham. But in reality there’s a lot of physics. Stuff happens afterwards. Think of The Day of the Jackal. The sniper assembles his weapon, fires his shot, but then de Gaulle bends forward to kiss the guy he’s pinning the medal on. There can be a lot of time between firing and hitting the target.’

This was the day on which Lee would pull the trigger on his new book. The funny thing was that he was having to talk about the old book. Although everyone thought it was new. It was just out – Personal. Reacher 19. This was what the interview was all about.

He was wearing denims, a charcoal Brooks Brothers jacket, and shoes with the laces taken out. He has this thing about laces. ‘Yeah, I got rid of all the shoelaces,’ he said. ‘They’re a pain when you’re travelling.’

The studio was great. Some kind of old warehouse in midtown. We were in the green room. Lee went off into make-up. The snacks were great: piles of fresh fruit – pineapple, melon, kiwi, banana, all neatly sliced up – gallons of coffee and tons of croissants. And there were any number of fabulous-looking women just sitting around looking fabulous. Don’t know what they were doing there exactly. One was called Whitney. She had ‘temporary tattooed jewellery’.

‘I want it to be the same but different.’ Lee was doing his thing with the TV interviewer. A couple in fact – a man and a woman. His ‘new’ book. Told them the story about his old father and how he had once asked him, when he was peering at a whole stack of books, how do you choose a book to read? And his dad had replied, ‘I want it to be the same but different.’ And Lee says, ‘I applied it to writing this one. It had to be the same – it’s the same old Reacher again, love him or hate him – but instead of roaming around America for a change, I have him getting on a plane to Paris, France, and London, England.’

I thought he didn’t really need to say ‘France’ or ‘England’, but then again maybe he did. He liked to spell things out. It’s a salient characteristic of his writing. What time is it? What road is this? Whereabouts are we? Don’t skim over the details. So that was the same too.

‘In pursuit of a sniper who is threatening world leaders. He arrested him once, now he has to nail him all over again.’

‘So it’s “personal”?’

‘Yes, but it’s also because his old army general tracks him down using an ad in the Personal column of the Army Times.’

The thing I liked about Personal was that the bad guys were known as the ‘Romford Boys’. Reacher ends up not in the middle of London, at Buckingham Palace, but in the suburbs to the east, in Essex. Romford is where I grew up, so I naturally took this swerve in the narrative as a homage to me. That was probably mad, but every act of reading is also an act of madness, because you have to assume that the writer is writing for me, specifically. I have this relationship thing going on with the author. So I was no more nuts than anyone else. Well, maybe a little more.

Lee admitted, when we were sitting about in the café later, that he was probably a little nuts himself. Although he began by denying it. (Obviously, he was still putting off making a start on the new book. He was enjoying the gorgeous feeling too much.) ‘I’m not a weirdo,’ he said, knocking back a cup of black coffee. ‘I know I’m making this all up. I invented Jack Reacher. He is nothing but a fictional character through and through. He is imaginary.’

He has this way of emphasizing particular words that I can only capture with italics.

‘On the other hand, with another part of my brain, I’m thinking, I am reporting on the latest antics of Jack Reacher. Hold on,’ and here he cupped his hand around one ear, as if listening intently, ‘what’s that? Let me note that down right now! The novels are really reportage.’

When he writes, he goes into a ‘zone’ in which he really believes that the non-existent Jack Reacher is temporarily existent. ‘I know I’m making it up, but it doesn’t feel that way. OK, so maybe I am a bit of a weirdo.’

I discover, as we’re driving back, that Reacher is very popular in prison. Lee gets fan mail from a lot of prisoners. He once paid a visit to a prison in New Zealand. The prison governor was worried about security. He needn’t have been. Hardened jailbirds love Lee. ‘I grew up in Birmingham,’ he says. ‘I’ve seen worse. And I was in television, therefore I’ve worked with worse.’

Later – OK, let me be more specific: it was around twelve – we’re back at his apartment, and Maggie Griffin is explaining how Killing Floor took off in the States. Maggie was one of the first readers of his first novel (in galley proofs) in New York, back in 1997. And she is still with him, as ‘independent PR adviser’. She is probably his number-one fan too. Back then she worked on Wall Street and was a partner in an independent bookstore, Partners & Crime. They made Killing Floor a ‘Partners’ Pick’. She would phone people up and say, ‘Buy three copies. It’s going to be collectable.’ She was right, of course. ‘One to read, another to share, and one to keep pristine. It’s going to be worth a lot of money.’ And it had a great and memorable cover (the white background with the red hand print over it).

She was the one who persuaded him to come to New York, on his own dime (as they say here). ‘Yes,’ she would say in her phone calls, lying her head off, ‘Putnam are flying him over.’

They sold a few thousand in the first weekend.

‘Yeah, I was a “cult hit”,’ said Lee. ‘A blip on the radar. I guess it’s been incremental since then. The odds against me being in this position are huge. But at the time we were just making it up as we went along. I never had a breakthrough moment really. Just a hard relentless slog in the middle years. Which is why I always have Reacher doing a lot of hard work.’

‘As in, for example,’ says I, ‘The Hard Way. “Yes, we are going to have to do this the hard way,” Reacher says, being deeply put upon and overworked by his tyrannical author.’

‘I never like to make it too easy for him – why should he have it easy?’

And then two or three books in, his agent says to him, ‘Have you heard about this Internet thing?’ Dinner at the Langham, next to the BBC. And Lee persuaded Maggie to build him what would become the poster-boy of author websites. Streets ahead. Leaving everyone else trying to catch up.

‘It probably helped,’ Maggie said, ‘when Bill Clinton came out as a fan. Clinton – that was like Kennedy reading the James Bond books.’

Maggie said that at the beginning the publishers had ‘misjudged’ the appeal to women readers.

‘They like the same things guys do,’ she said. ‘Violent retribution. They want blood on the page.’

We were just sitting around talking, still delaying the beginning. It was a day of postponement. Lee was pondering Amazon’s influence. Amazon have this thing of showing you 10 per cent of a book to suck you in. ‘Some writers,’ Lee was saying, with a degree of scorn, ‘some writers have started writing the first episode in their books to fit the 10 per cent and kick the book off. They’re actually calculating exactly how long their chapters should be.’ Lee didn’t want to be one of those writers. He didn’t want Amazon telling him how to write a book. He didn’t want anyone telling him.

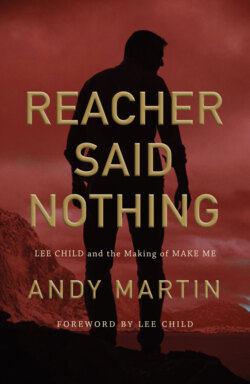

I knew things went wrong in publishing. Sometimes embarrassingly so. A friend of mine had her book printed with someone else’s cover on it. ‘They go wrong all the time,’ Lee said. ‘This is an industrial process with hundreds of millions of manufactured items.’ He’d done an industry event recently where the publishers had a big pile of books. A reader came up to him with one of them which had a perfectly fine cover, but was completely blank inside. Lee apologized. Signed the book as normal. But this time he wrote in it: Reacher said nothing. It was one of his recurrent phrases, almost a catchphrase, if saying nothing could be a catchphrase.

‘Reacher often says nothing,’ Lee said. ‘He shouldn’t have to be wisecracking all the time. He’s not into witty repartee. He is supposed to do things.’ Basically, Reacher made Lee Child sound like Oscar Wilde. Not that he was an idiot (Reacher, I mean). More of a particularly taciturn, very muscular philosopher. Lapidary. Succinct. More at the Clint Eastwood end of the spectrum. With just a dash of Nietzsche and Marcuse.

Then we went to the radio studio a few blocks away (Lee would write about how we turned left to go north on Central Park West as we came out of his building). Which is when we had the John Lennon moment (somewhere between 86th and 87th).