Читать книгу Reacher Said Nothing - Andy Martin - Страница 15

4 CHAPTER ONE (CONTINUED)

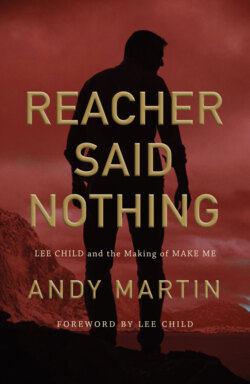

ОглавлениеLee is a distinctive guy to look at. About six foot four. Tall and stringy-looking. Strong chin. Piercing blue eyes. Reddybrown hair. Late fifties but well preserved. Verging on elegant. Longitudinal. Someone had said to him ‘You should play Reacher’ (in the movie). He had replied, ‘My body mass would just about fit into one of his arms.’ (Reacher 250 lbs; Child more like half that) Still, you can pick him out in a crowd. Or walking across Central Park. He has a long, lazy, loping stride. Half Robert Redford, half Jacques Tati. With a bit of Walter White thrown in for good measure.

He was doing a down-the-line interview with a radio show in England. Now even Lee was starting to worry about putting off the writing. Maybe it was one show too many.

‘The book came out yesterday in the UK. It’s already sold a phenomenal number. So this is not strategic. But I love Simon Mayo – the guy actually reads the books. I’m doing this show because I want to be on it.’

We went in. Bumped into an old guy in braces and baggy trousers hitched high. A producer or something.

‘So what is this book?’ he says.

‘It’s a thriller. I hope.’

‘So it’s a movie, is it?’

‘Well [cue sound of Lee gritting his teeth], it might become one ultimately.’

He hates the movie assumption. I have taken a vow to keep off the subject of Tom Cruise (who played Reacher in the Jack Reacher movie, based on One Shot). He has already received around one million emails from fans saying ‘YOU SOLD US OUT, YOU BASTARD!’ or words to that effect. He sends out a tweet about what he had for breakfast and they all tweet back to him, ‘But why Tom Cruise?’ Some people said, ‘What about Daniel Craig?’

‘Well, what about Daniel Craig?’ I said.

‘He’s even shorter!’ Lee shot back. (He had actually met Daniel Craig and knew him well enough to call him ‘Danny’.) Likewise Clint Eastwood: ‘They’re all shrimps!’

The producer in London is a fan, more well versed than the old guy. ‘If you ever want a character who’s a slightly stressed-out radio producer,’ she says, rather seductively, ‘feel free to use me.’

Simon Mayo, the presenter in London, says, ‘We’re doing Jack Reacher songs this afternoon. This one is “The Wanderer”.’

And then: ‘Lee Child live from New York … The one and only Lee Child!’

All the callers wanted to be a character in a Reacher book. Possibly have a romance with Reacher. Or even be on the receiving end of a crunching Reacher head-butt. Mayo launched in with a story about how Lee has a character named Audrey Shaw in The Affair. The real Audrey Shaw’s son, aged fourteen, had written to him, telling him she was a total Reacher fan and would he mind using her name. So he did. ‘She was a fan,’ Lee explained, ‘and it’s a great name. Perfect for the character.’

A lot of people were wondering about Reacher getting older. I’d heard the question asked a few times – how old is he now? Is he over the hill or what? Lee reckoned he was around forty-eight now, maybe a bit older. ‘I used to be very specific but now I just don’t mention it.’ And they wanted to know if Lee was going to kill him off one of these days. They were expecting it all to come to an end. Twilight of an idol. ‘It’s my readers who are keeping him alive,’ Lee says.

We walked back to his place. Unmolested by fans or assassins. As far as I could work out, you either wanted to be Jack Reacher, make love to him, or kill him off for all time. Or possibly some combination of the above.

The Lee Child apartment was like a very comfortable library. Hushed. Orderly. Lee had had white-painted bookshelves installed all around and there was still space for more books. He had a lot more in boxes stashed away somewhere.

‘I’m paying for it with the advance on the next book,’ he said. He looked around and grinned. ‘I haven’t earned it yet. I’m living in an apartment that was bought with a book that hasn’t been written.’

‘Nervous?’ I said.

‘It’s more I feel I have to really earn the apartment. It’s like it’s on a mortgage – I bought it with promises. Now I have to deliver.’

Lee wanted to get down to work, but he thought we’d better have some lunch first. It was about two o’clock. He made us some toast. We had cheese (a choice of Cheddar or Stilton – he had a big hunk of Stilton) and marmalade to go with it. And a smoothie (he had apricot, I had strawberry). We sat down in the dining room to eat our toast. It was a lovely old French farm table of some kind, chunky and rustic-looking.

I started telling him about rotten jobs I’d done in the past, how I’d lasted less than an hour in one of them, at a metal factory. Lee had tried a few other jobs in his youth. He didn’t like any of them. It wasn’t that he didn’t like the work, he didn’t like the workmanship. In the jam factory, for example. ‘It was all sugar paste, nothing but sugar paste. If you wanted apricot jam you threw in some orange colour. Strawberry – throw in some red. It was like you were painting jam. What about raspberry with all those little pips? No problem – here, we’ll throw in some tiny wood chips.’ He was really outraged by how bad it was. ‘Nothing was real. Nobody cared.’ He felt responsible for people eating a load of rubbish just masquerading as jam. They were being conned. Lee wanted it to be good jam, whatever flavour it was.

He once had a job in a dried pea factory. He couldn’t believe it: ‘Birds were perched up there on the rafters, way over our heads, and shitting into the peas. Nobody cared. That is how it was.’

And another job in a bakery. It wasn’t a traditional bakery. He wasn’t kneading any dough. Or putting loaves in ovens. Everything was on an assembly line. His job was to take loaves off the horizontal belt and stack them on some kind of vertical system. But he couldn’t get the hang of it. ‘There were all these loaves coming off the line. I was supposed to clamp seven loaves together and transfer them from the belt to the stack. But I just couldn’t manage to do it. Seven loaves, at one time. They would allow you to drop one or two in an hour. But I kept on dropping them. I just couldn’t get my arms tight enough around the loaves to hold them all together.’ He showed me how his physique was all wrong for the job. He was too stringy. His arms were too long. ‘I kept on dropping them. They were all over the place. They sacked me inside an hour. I deserved to be sacked. I was no good at it.’

He really wanted to be good – to find something he could be good at. He thought he was good at television. Then he got sacked from that job too.

We were about to go into his office. The novel factory. I think I was more nervous than he was. And I had a sense of quasi-religious awe too – I was about to bear witness to the genesis of a great work, the Big Bang moment. ‘Do you have anything in mind?’ I said.

Because this was the key thing about the way Lee Child writes. The thing that drew me to write to him and break into his apartment and watch him working. He really didn’t know what was going to happen next. ‘I don’t have a clue about what is going to happen,’ he would say. He was a writer who thought like a reader. He had nothing planned. When he wrote to me he said, ‘I have no title and no plot.’ But he said I could come anyway. He didn’t think I would put him off too much. He relied on inspiration to guide him. Like a muse. Or the Force or something. Something basic and mythic, without too much forethought. He liked his writing to be organic and spontaneous and authentic. He feared that thinking about it too much in advance would kill it stone dead. But still he had a glimmering of what would be. He knew the feel of a book.

‘The opening is a third-party scene, I know that, right at the start. A bunch of other guys. So it has to be a third-person sort of book. Reacher doesn’t know what is happening. He’s not there yet.’

‘Do you see something in your mind, or what? Is that what you mean by “scene”?’

‘It’s visual, yes. In the sense of seeing the words – I can almost see the paragraph in my mind. The physical look on the page. You have to nail the reader right there, on the first page. The uncommitted reader. And I can feel it. The rhythm. It’s got to be stumbly. It’s tough guys talking. I have to get a hint of their vernacular. But, at the same time, it has to trip ahead. A tripping rhythm. Forward momentum.’

I think it was around then that Lee started talking about euthanasia. He was in favour. There is a lot of thanatos in his books, not so much of the eu. ‘I can die right now. I’m fine with that.’ He dismissed the recommendation of a friend to go off to a mountain in Austria and chuck himself off (he thought you might change your mind by virtue of the fresh air and the landscape). Turned out he had some plan, when the time came, involving a veterinary supplies store down in Mexico and a rather powerful cocktail of morphine and horse tranquillizer. Had it all worked out.

‘Come on, man,’ I said, although I basically agreed with him. ‘Think of your readers! Anyway, I’m stuffed if you die. I’ll have to finish your book for you. Pretend you’re still alive and steal all your earnings.’