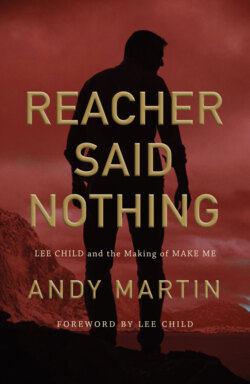

Читать книгу Reacher Said Nothing - Andy Martin - Страница 20

9 THE SONG OF REACHER

Оглавление‘Professor Andy Martin,’ Lee says to me. ‘Come on in.’

Apparently Maggie had been checking my academic credentials, such as they were. His people didn’t want some maniac creeping up on him in the middle of the night. Or stealing his Renoir or whatever. Technically, I wasn’t even a professor (I was only ‘Doctor’), but Lee didn’t seem too worried about the detail. He had an unwarranted faith in the moral integrity of academics.

He made coffee. He reckoned there was some milk somewhere but he wasn’t too sure about its status. I took it black.

Lee hadn’t shaved; he had Reacher-worthy stubble. But he was in jovial mood, really enjoying being at the beginning of something. He liked it so much he didn’t really want to leave the beginning alone.

He had been thinking about the word ‘like’. Of course it was in the second sentence of chapter one – simile – but he was thinking of the contemporary verbal tic (I’d mentioned it in some article he had read to do with roaming around New York like a Trappist monk for twenty-four hours). ‘It’s actually quite economical. I like like. When someone says to you, “He was like ‘I’m so into you’,” it’s not that he actually said, “I am so into you.” It’s more, “He behaved in such a way that a reasonable observer might conclude he was so into me.” Which carries an element of doubt. Some kind of approximation has been conceded. So really you’re abbreviating the sentence, and implicitly acknowledging the power of impression, while also acknowledging the impossibility of knowing for sure … but it’s all still there. What was it Ezra Pound said – all poetry is condensation?’

His own chapter one remained stubbornly condensed too. We went into his office and he gave me a fresh printout of page one. There still wasn’t a page two. It was Friday, September 5. He had started the whole ball rolling on Monday and he was still on the first page. He hadn’t added substantially to what he had already written. But he had been finessing. Now he was focused entirely on what Reacher was doing or thinking at the moment he got off the train. Everything was contained in that moment.

‘What do you think of the word “onto”?’ he asked me.

‘I don’t have strong views,’ I said, knocking back the coffee.

‘To me it sounds ugly. I just don’t like onto. But I’ve written Reacher stepped down onto a concrete ramp. That is ugly. So I’ve changed it. Look.’

I looked down at the page in front of me. Jack Reacher stepped down to a concrete ramp. The on part of onto had gone.

‘It’s better, don’t you think? I’m not having onto. Never liked it.’

‘… down to a concrete ramp. Well, you changed what he is stepping down onto; I guess you might as well change the preposition as well, while you’re at it. To will work.’

‘I was thinking about what you were saying about dialogue. There’s no dialogue at the beginning. But it’s all dialogue, in a way, if it’s first person. Nothing but. There’s a Nevil Shute novel. The alleged narrator meets some old mate of his in a gentlemen’s club, who proceeds to regale him with some tale – and that is the story.’

‘A bit like those old Isaac Bashevis Singer novels.’

‘Exactly. Jacob comes up to him and tells him a story. It’s all dialogue, really.’

‘But that was Personal. First-person narrative. This is third person. So it’s not dialogue. It’s reportage.’

‘It’s funny. I feel as though I’m still just quoting. I did do two first-person narratives in a row. But generally I try to vary it. This time, I didn’t feel it had to be third person. There was no real sense of obligation. But the thing is, I knew it was something happening beyond Reacher’s knowledge or perception. So it couldn’t be his voice at the beginning. It had to be someone else’s. Third party, so it’s third person. It’s all down to the voice – or voices.’

I was back on the couch. Lee had given me his one-page print-out and I was – I was going to write leafing through it, but how could I be leafing through a single page? Anyway, I was reading it. And naturally I was wondering what was coming next. Where does Reacher go from the concrete ramp?

But before we got onto – or rather to (delete on!) – that, we had to consider the question of ‘bigger than’ versus ‘as big as’.

‘Hold on,’ says I, ‘you’ve changed this bit, haven’t you?’

‘It had to be,’ he said. ‘I was trying to work out why I wasn’t really happy with a grain silo bigger than an apartment house. Obviously it’s adjacent to Reacher himself, so I wanted to associate him with the silo. But then he is associated with Keever too. So I realized I needed to echo the first sentence.’

Moving a guy as big as Keever … a grain silo as big as an apartment house. It made sense. The first section starts with the mysterious Keever. The second section switches to Reacher. But there are parallel constructions – to do with comparative sizes – hooking the two of them together. At one level, the novel was all about momentum, forward movement, the sprung or ‘tripping’ rhythm that would ‘lead the reader by the hand’ through the narrative; at another, it was all about the links that cut right across the story line – little subterranean echoes, rhymes, parallels, repetitions, variations. There was a horizontal, linear, syntagmatic axis, propelling you forward, but there was just as much a vertical, paradigmatic axis, a network – at the level of phonology and semantics – holding everything together, keeping it tight and connected. It was prose, of course, but it was just as obviously poetry. Make Me is the song of Reacher.

Make Me, that hugely resonant and imperative title, had just acquired another meaning in my mind: this was the novel itself speaking to its author, its maker, crying out to him, Go on then, make me, and make me as good as you’ve ever made anything.