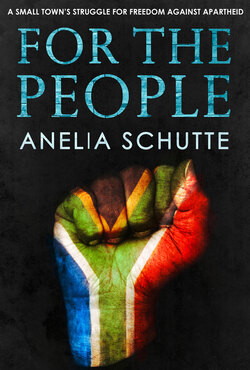

Читать книгу For The People - Anelia Schutte - Страница 10

ОглавлениеIntroduction

I was born into apartheid. From 1978 until Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1990, it was the only reality I knew.

My parents had grown up with it too. When the National Party came into power in 1948, both my mother and father were four years old.

The National Party government introduced a system of racial segregation that would become known as apartheid – ‘separateness’ – enforced by a series of acts and laws. Land was separated into homogenous areas for white, coloured and black. Children of different races were forced to go to different schools. It became illegal for white people to marry people of other races – or, under the ‘Immorality Act’, even to have sex with them.

As our country became scorned, sanctioned and boycotted by the rest of the world, it became ever more insular, our press heavily censored by the apartheid government.

I knew very little of this history before 2007, when I started working on this book.

Growing up in a small town in South Africa, I never questioned apartheid. It was just the way it was – a refrain I’ve heard from many white South Africans since.

I was twelve years old when Nelson Mandela was released. Preoccupied with school and boys, I was only vaguely aware of what was going on.

Many white adults were nervous about what might happen at the time. Some of the more right wing stockpiled food and guns in anticipation of what was surely an inevitable civil war as apartheid laws were abolished and black people’s voting rights reinstated.

At sixteen, I was too young to vote in South Africa’s first democratic election, which saw the African National Congress, or ANC – for years treated as a terrorist organisation – become our new government, and Nelson Mandela our new president.

To everyone’s relief, the worst fears were unfounded. Where the apartheid government enforced segregation and oppression, Mandela encouraged forgiveness and reconciliation.

The most unifying gesture of all was his appearance at the 1995 Rugby World Cup, wearing the green and gold of our national team, the Springboks.

In our living room, I cheered with my family and the rest of the country when he lifted that cup with white rugby captain Francois Pienaar.

Everything was going to be OK.

Things changed quickly. National service was abolished so soon after the election that my brother, who’d simply assumed he’d go to the army straight after school, still went despite being one of the first generation of white boys who didn’t have to. He simply didn’t have a plan B.

He was one of very few people in the army that year who weren’t coloured or black.

When I finished high school in 1995, I applied for a scholarship to an advertising school in Cape Town, as the tuition fees were more than my parents could afford. I was told my skin was the wrong colour. I still went, after my parents remortgaged their house to pay for it.

One of the upsides of our new democracy was that the world opened up to us in a way it never had before. As a result, a new wanderlust broke out among young white South Africans. My oldest brother was the first in our family to leave, just two years after Mandela’s release, to go backpacking around Europe. Having had a taste of the world, he came back to South Africa just long enough to get a qualification before returning to Europe, where he settled in the UK and eventually married a British woman.

When my family went to London for the wedding, my mother got her first-ever passport at the age of fifty-three. My father and I already had passports, but only because we’d both been to Namibia – my father on a one-off fishing trip, and me for a week of canoeing the year before.

In London, I was amazed to share the Tube with well-dressed black people who spoke not in African accents but British ones.

Having had a taste of the world beyond South Africa, the travel bug bit me too and in 1999 I left, aged twenty-one and armed with a working holiday visa for the UK.

Those of us who left were criticised by the government for creating a ‘brain drain’ in the country at a time when it was hard at work rebuilding itself. While it’s true that many people left because of the limited job prospects for white people in a country that was hastily redressing its race balance, my own motivations were more personal. I was in an enforced break in my copywriting career after losing my job at an ad agency. And I had fallen for a man in London during the trip for my brother’s wedding. The relationship didn’t last, but I never went back to live in South Africa.

In London, I quickly got out of touch with what was going on back home. I went over to see my parents every eighteen months or so, but with only two weeks there at a time, I became a tourist in my own country.

It was on a writing retreat in Spain that I first started questioning the way things were back home. By then I was a British Citizen through naturalisation, having lived in England long enough to get a British passport. South Africa felt very far away.

But when I interviewed a local farmer in Aracena called Alfonso Perez, I suddenly felt myself drawn back to my homeland. Alfonso told us one story after another of the Spanish Civil War and how it had divided his country, with friends and even family finding themselves on opposite sides of a violent struggle.

I couldn’t help drawing comparisons with South Africa, and faint memories started flickering in my mind. Pieced together from several phone calls to my mother in South Africa, one of those memories became a short story.

I never thought it would become the prologue to a book. My then husband, a Brit and also a writer, put the idea in my head on my return to London. ‘There’s a book here,’ he said. ‘And only you can write it.’

At first I laughed it off: I didn’t have a book in me.

But then the memories started coming back: snippets of stories my parents had told me when I was growing up of my mother’s work in the townships.

I became curious, wanting to know more about those stories and the stories behind them.

At first my mother hated the idea.

‘I was just doing my job,’ she said.

But she was keen to encourage my writing and eventually gave in. Just three months after my time in Spain, I used a Christmas trip to South Africa to start doing some research.

It was a frustrating process. My mother’s memory was sketchy in places, leaving big gaps in the story. Many of the places that might have kept official records from that time were closed for the holiday season. And without a clear contextual framework or timeline, the few interviews I did made little sense to me.

I realised if I was going to do this, I had to do it properly.

A year and a half later, I took three months off work and went back to South Africa armed with a laptop, a Dictaphone and a crash course in interviewing from my boss, an ex-investigative journalist.

This time I wanted to hear not just my mother’s side of the story. I wanted to speak to the people who lived in the townships, and the authorities who’d built them. I wanted to speak to the people who’d worked for the apartheid government then, and the people who work for the ANC government now. I wanted to speak to the rioters who’d stood up for their human rights, and the policemen who’d arrested them.

This is what I found.