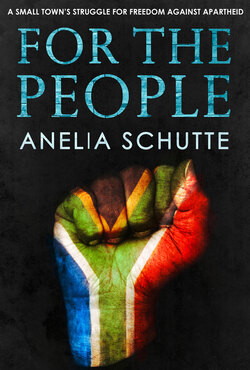

Читать книгу For The People - Anelia Schutte - Страница 18

ОглавлениеChapter 8

1972

Owéna hadn’t come across many black people in her life. Growing up in the Western Cape, the non-white people she encountered were mostly coloured. That was because the government had declared the entire region a ‘coloured labour preference area’, meaning that, by law, manual and semi-skilled jobs were to go to coloured people over black.

If a black person wanted to try their luck getting a job in the Western Cape, or indeed anywhere in South Africa, they also had the pass laws to contend with.

The pass laws were part of the apartheid government’s plan to restrict the influx of black people into ‘white’ South Africa from the African homelands. Created by the National Party government in the 1950s, the homelands were ten regions within South Africa’s borders where the different black tribes were meant to live, develop and work among their own. Despite black South Africans outnumbering white by around eight to one, the ten homelands together made up just thirteen per cent of the country’s land.

Encouraged by the government, several of the homelands became self-governing, quasi-independent states in 1959.

In 1970, a law was passed that made all black South Africans citizens of their homelands and no longer of South Africa, removing their right to vote and making white people the new majority.

If any black person wanted to travel outside the borders of their homeland, they had to carry a passbook at all times. And if they wanted to live and work in a South African town or city, they needed one of two things in their passbook: either a so-called ‘section 10’ stamp, or a temporary work permit.

The section 10 stamp gave the bearer of the passbook permission to live somewhere permanently, usually because they were born there. To live and work anywhere else, they needed a work permit that had to be renewed every year. An employer had to apply for that permit on behalf of a worker, so that no black person could move between towns and cities without having a guaranteed job at their destination. The work permit usually covered only the worker, not his wife or children, who had to stay behind. Anyone caught without the necessary paperwork was evicted and sent back to where they came from – a job that fell to the Bantu Affairs Administration Board.

Formed in 1972, Bantu Administration, as most people called it even after its name changed a number of times, was the government department responsible for the ‘development and administration’ of South Africa’s black population. As an enforcer of apartheid, the Administration was despised by the black people and in this context, the word ‘bantu’ – Zulu for ‘people’ – became offensive by association.

The government’s influx control meant Knysna, like the rest of the Western Cape, didn’t have much of a black population in 1972.

The few black people in Knysna – those who had been born and raised in the area and so had the necessary section 10 stamp to stay there – lived among the coloured people in places like Salt River until they were evicted along with their coloured neighbours.

But the black people couldn’t go to Hornlee with its schools and its churches and its community centres and sports fields. Because, under the Group Areas Act, black and coloured couldn’t mix.

With no township of their own to go to, they ended up squatting in shacks in the hills around town, on land that was undeclared for any particular colour.

In a desperate attempt to give their families a better life, many black people attempted to get into Bigai by pretending to be coloured, even changing their surnames to sound less African.

The authorities had various tests and techniques to catch out those imposters. One was to check whether the person could speak Afrikaans, as most coloured people spoke it as their first language. A black man from the Transkei, the official Xhosa homeland, would never have had the opportunity to learn the language, and so would be exposed as ‘acting coloured’ if he failed to answer a question in Afrikaans. Alternatively, a policeman might ask that black man to say ‘Ag-en-tagtig klein sakkies aartappeltjies’, an Afrikaans phrase that simply meant ‘eighty-eight small bags of potatoes’, but had so many guttural sounds and inflections completely alien to the African tongue that few Xhosa people could pronounce it.

Fortunately, many of the Xhosa people native to Knysna spoke fluent Afrikaans, having grown up among the coloured community. And so there were some of them who passed the language test and made it into Hornlee.

Those who didn’t returned to the squatter camps.

Whereas the Western Cape had no black population to speak of, it was a very different story in the neighbouring Eastern Cape.

With no coloured labour preference and a border shared with the poverty-stricken Transkei homeland, the Eastern Cape was a popular destination for migrant Xhosa workers looking to feed their starving families. Once there, they worked in factories and on farms, in gardens and on building sites, anything they could get to be able to send some money back home.

But the black workers far outnumbered the available jobs in the Eastern Cape. Desperate for money, many of them turned their attention to the Western Cape. And when they heard rumours of job opportunities in Knysna’s sawmills and furniture factories, one black man after another took his chances and moved there, work permit or not.

From towns and cities like Umtata and East London, they hitchhiked to Knysna, a long and arduous journey often undertaken on the back of a Toyota or Isuzu bakkie, the pick-ups popular with South Africans and especially farmers.

Those people with work permits were often put up in compounds on their employers’ premises. Those without permits, however, had no choice but to join the squatters in the hills, where they lived in fear of getting caught.

The Bantu Administration van was a familiar and feared sight in the squatter camps. Raids were common, often at three, four in the morning in an effort to catch people while they were sleeping.

But word spread quickly, and the ‘illegals’ were good at hiding.