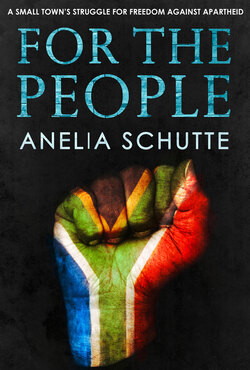

Читать книгу For The People - Anelia Schutte - Страница 13

ОглавлениеChapter 3

1970

Owéna Schutte opened the first of many suitcases and unpacked a pair of mud-caked sandals that she wouldn’t be washing anytime soon.

The mud was from the plot of land that she and her husband, Theron, had recently bought. It was a decent-sized patch on the outskirts of Knysna where they were building a house an architect friend had designed for them. In the meantime, they were staying in the local boys’ boarding house with some of Theron’s fellow teachers from the Knysna High School.

Until their house was built, the mud on her sandals was all Owéna had to show for their purchase. Their own piece of Knysna.

Married for nine months, Owéna and Theron had moved to Knysna from Cape Town, where they’d rented a small flat in a suburb near the school where Theron got his first teaching job after university. The flat had been an improvement on the caravan they’d lived in for the first three months of their marriage, but they were thinking of starting a family and the city wasn’t where they wanted to raise their children.

Looking for a quieter life, Theron applied for posts at schools in two very different parts of the country. One was in Upington, a farming community in the arid north-west of South Africa that was known for its exceptionally hot summers and frosty winters. The other was in Knysna, the pretty coastal town known mainly for its timber and furniture industry.

When both applications were successful, Theron, a keen fisherman and woodworker, chose Knysna.

Soon after Theron accepted the position, Owéna received a phone call. Unsurprisingly for a town as small as Knysna, word had got out that the new biology teacher’s wife was a trained social worker. And the Knysna Child and Family Welfare Society was in desperate need of one.

Owéna was torn at first. She did need a job, but her only experience since graduating from Stellenbosch University had been working with the aged in care homes, where she organised social groups and concerts to keep their minds active. It was gentle work and although it was always sad to see one of the old dears pass away, there was the consolation of knowing they had all lived long and usually full lives.

Working with children was a very different job, and one for which Owéna felt extremely under-qualified. Would she be able to cope with seeing a child who’d been abused or neglected? Or taking a child away from his parents to put him in foster care?

Adding to her crisis of confidence was the job title: senior social worker. The society already had two social workers who were far more experienced than Owéna, especially when it came to dealing with children and families. Yet she was offered the senior position – with the higher salary that came with it – only because, she suspected, she was white and they were coloured, or mixed-race.

Owéna didn’t know much about politics. She’d been born in 1944 to a conservative Afrikaans family who, like most Afrikaners, respected the government’s authority and accepted its decisions unquestioningly – even when, from 1948, that government was the National Party with its separatist ideals.

Owéna’s upbringing wasn’t a particularly privileged one, not by white South African standards. Her father was a station-master for the national railways, a job that hardly paid a handsome wage, and her mother was a housewife who’d married in a simple sundress because her family couldn’t afford a wedding gown.

Owéna was just four years old when the National Party came into power and introduced apartheid. So she didn’t find it strange that there was a separate queue at the post office for black and coloured people. It was just the way it had always been. She didn’t even notice the separate counters in butchers’ shops, where the prime cuts were displayed behind glass at the whites-only counter, while black and coloured customers had to take whatever sinewy off-cuts they got. And when Owéna used a public toilet, she never stopped to ask why she could only go through the door euphemistically marked ‘Europeans only’ when she had never been to Europe.

Like most South Africans, Owéna had never travelled anywhere beyond the borders of her country. It was just too expensive, and she had no real desire to see the rest of the world.

Despite her blinkered view on the world around her, Owéna still felt uncomfortable at the idea of going into a new job above two colleagues based purely on the colour of her skin. But, needing to work, she accepted the job.

She spent her first day in Knysna in bed with a migraine.

If Owéna had worried that the coloured social workers would hold a grudge against her, she needn’t have. When she turned up for her first day at the Knysna Child and Family Welfare Society – or ‘Child Welfare’, as the locals called it – her new colleagues couldn’t have been friendlier or more welcoming.

Good humour was necessary in their line of work. Child Welfare dealt with cases ranging from child abuse and neglect to alcoholism and domestic violence. Clients came mainly from Knysna’s sizeable coloured community, with the occasional case from the few black families who lived among the coloured. White families’ welfare, on the other hand, was seen to by a Christian organisation in town.

While Owéna was working a six-day week at Child Welfare, Theron was teaching in the mornings and working on the house in his spare time. He had found a coloured bricklayer and two black labourers to do most of the building work, leaving him to make things like the window frames and staircases where he could put his woodworking skills to good use.

With no workshop or equipment at the building site, Theron did most of the woodwork at the boarding house where he made the window frames by hand, cutting the joints with the minute precision he’d mastered under the microscope in biology class.

The people of Knysna soon got used to the sight of the new teacher and his social worker wife driving through town with their window frames, some three metres long, tied to the roof of their Borgward station wagon.

At the building site, Owéna helped as best she could at the weekends, happily holding this here and hammering that there as instructed by Theron. The house was coming along nicely, and she allowed herself to daydream of the family they would raise there.

Little did she know that a much bigger development was under construction not far from theirs. To the east of Knysna, just on the other side of a hill, new roads were being scraped, water pipes were being laid, and one identical house after the other was being built.

Knysna’s first township was underway.