Читать книгу Shiptown - Ann Grodzins Gold - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Entries

Five Gates and a Window

From the remote time when walled towns and royal strongholds were first built it was instinctive for men to attribute anagogical, allegorical and topological meanings to gateways. (Smith 1978:10)

I first arrived for a long-term fieldwork spell in Jahazpur on 5 August 2010. I was sixty-three and hardly a novice. Over a period of time extending back more than thirty years I had pursued diverse anthropological projects in this region of Rajasthan. Moreover, I had already spent several nights in Jahazpur and met a number of people there during three consecutive summer visits in 2006, 2007, and 2008. My aim now was to study the nature of small-town life in North India in what I planned would be a wide-ranging, if far from comprehensive, fashion. I had proposed to ground my topic by looking at three specific types of places: neighborhoods, shops, and shrines. These were all around me, in delightful if daunting abundance. Even so, methodological avenues eluded me. How to begin finding meaningful patterns in everyday routes and activities?

Once again, I was working collaboratively with Bhoju Ram Gujar, but only when his schedule as a full-time middle-school headmaster and dedicated government servant permitted. He fitted my work as best he could into the cracks and crevices of what seemed to me to be an inordinately busy and complicated life.1 Bhoju himself, while eager as ever to embark upon ethnographic research, did not radiate his usual confidence as we confronted this vast new space of investigation.

In the past when we had worked together in villages, Bhoju considered himself fully cognizant of, and comfortable in, the social milieu; his gifts as an interlocutor were unparalleled. Now, well-educated and well-traveled though he was, Bhoju remained a village-born person only lately come to town. Although it wasn’t in his nature to declare it, I could tell that Jahazpur society was partially mysterious to him, almost as opaque in some respects as it was to me.2 An economy ruled by trade, not farming, was certainly new territory for both of us. Some important groups here—for example, the former butchers and the former wine sellers—were not present at all in Ghatiyali, Bhoju’s birthplace and my previous fieldwork base.

It says something of significance about the kind of place Jahazpur is that Bhoju and I were initially baffled by a very strong contrast between Jahazpur and Ghatiyali. Ghatiyali was the second-largest village in the twenty-seven-village dominion of Sawar. Most people living within that former kingdom, even in the late 1990s and early 2000s, possessed vivid memories or knowledge of the time preceding India’s independence in 1947 when kings had ruled. They particularly recollected and could tell stories about the last king of Sawar, who had died without progeny the same year that India gained freedom from colonial rule. Even those far too young to have actual memories produced stories about Vansh Pradip Singh, a ruler so attentive to the goings-on in his estates that he was said to have personally and literally sniffed out poached game from his ramparts and sent his guards to arrest whoever was cooking it (Gold and Gujar 2002). Moreover, as recently as 2010 a member of the former ruling family who resides at least part of the time in Ghatiyali’s fort won a local democratic election there.

Jahazpur by contrast was located well beyond the olfactory range of rulers whether they were based in Udaipur, Ajmer, or even relatively nearby Shahpura, and whether they were Hindu, Mughal, or British. The pervasive memories of a “time of kings” that we had relied upon for our research on environmental history in the kingdom of Sawar were perplexingly absent here. Jahazpur politics inside the walls is dominated by merchants, Brahmins, and Deshvali Muslims (the three groups that own the most qasba land as well). In greater Jahazpur—the Nagar Palika, or municipality, incorporating twelve hamlets surrounding the town—Minas have put their numbers to work in block voting and triumphed in a series of recent mayoral elections.3

Participation in Jahazpur politics by members of the former ruling class, the Rajputs, is negligible. Mansions belonging to families once connected with royal power are empty, overgrown, and crumbling; no one in the general public seems to know or care where the owners went. Sawar’s fort remains inhabited by the ruling lineage, but Jahazpur’s is in ruins and long ago was stripped of anything valuable that could be removed (except for images of the gods that still abide there and continue to receive worship and service). Rumor had it that Jahazpur fort had been put up for sale by the government. I have not been able to document this assertion, but a few people jokingly proposed that I purchase the ruins and open a heritage hotel. In sum, in contemporary Jahazpur, the decline of Rajput fortunes seemed complete. Those few remaining members of families slightly related to royalty are poor, disempowered, and command scant interest from the public.4

Figure 4. Maps of Rajasthan and Bhilwara District (produced by Joseph W. Stoll).

Bhoju was initially stunned at how few people in Jahazpur could even name the last ruler, and certainly no one spoke of royalty with any kind of affection or reverence, not even with intense hatred. Much of what we did glean through persistent questioning about the former rulers in these parts had to do with dissolute behavior: unsavory alliances, substance abuse, crushing debt. For the most part, these figures from the past were not a live topic of conversation. This could not have presented a greater contrast with our previous experience.

For a month, during which there were predictable preoccupations connected with domestic and bureaucratic arrangements, I flailed around to match my research agenda to my whereabouts. To counter my hesitations, Bhoju initiated some excellent pragmatic steps. First, he rustled up persons willing to be interviewed on a general level about town and place. These interviews, mostly with busy, senior members of Jahazpur’s merchant community, we conducted in the evening after business hours. Bhoju’s two older daughters, meanwhile, were easily persuaded to help me meet and have conversations with neighbor women, a morning enterprise that proved not only productive but pleasant, even as it stimulated a whole new set of concerns around gender and neighborhood (see Chapter 3). My neighbors lived in Santosh Nagar, on the outskirts of town, where we had decided to settle for excellent reasons. But I worried about the need to keep my attention focused on Jahazpur proper, the qasba, “inside the walls” (kot ke andar) as the local phrase went.

We were into September, and there was plenty of daylight to spare. Bhoju’s school was still on the hot season schedule, so he normally returned fairly early in the afternoon. Bhoju suggested that we survey the built landscape, especially those landmarks or places in which history was embedded. Of course, I had been several times up to the fort on the hill for the hike, the views, and to visit the tomb of Gaji Pir and adjacent Muslim shrines. But now we would tour the flats systematically and visit the old qasba gates. I had already passed in and out of the grandest gate, the one connecting the bus stand to the market, countless times; but I had taken only sporadic note of the others.

Figure 5. Hand-drawn map of Jahazpur, selected sites (original by Bhoju Ram Gujar, redesigned and produced by Joseph W. Stoll).

Although portions of the old ramparts are no longer standing, Jahazpur’s market and residences were originally contained within a fully walled area. Five major doorways remain intact, three of which lead to the exterior; another opens on an important outdoor square, and another marks the significant Muslim presence within Jahazpur qasba and sets apart the entrance to the mosque as sacred space (Bianca 2000). Lastly, there is a small gate to the exterior, more a window than a doorway. This “Window Gate” was regularly included when our most thorough informants enumerated ways to enter and exit the qasba. That made a total, you might say, of five and a half gates—or as I have put it in my chapter title, five gates and a window.5

We had already conducted some interviews with elderly people whose memories reached back into the 1940s, and there would be many more. We heard repeatedly that right up to Independence, the gates were locked at night, some manned by watchmen. For industrious farmers who lived in the town but farmed in the surrounding countryside, the walls and locked gates could become major inconveniences. I don’t know when the walls were constructed, exactly. But the process of walling market towns to protect from robbers appears to have been a nineteenth-century process elsewhere in the region.6 At certain seasons, farmers must work long past dusk. They were forced to sleep in their fields. Even if a watchman might allow a human to climb through a small window set within the massive door, the big doorways through which livestock might pass were kept closed throughout the night.

These practices were explained to us repeatedly as intended to protect the town with its goods from thieves and wild animals. The wall portions that are still standing have signs of past military functions (slits through which rifles or arrows could be shot). However, although some notations in historical accounts mention battles involving Jahazpur’s fort on the hill, I found neither written nor oral traces of battles around the town itself.

Bhoju and I toured all the gates by motorcycle, me in my usual sidesaddle position behind him. This gave us a happy sense of continuity with our previous successful research in the twenty-seven-village kingdom of Sawar, much of which relied on similar if more grueling motorcycle excursions (Gold and Gujar 2002). It also provided a feeling of current accomplishment. At each gate we disembarked, and I took photographs. When we looked at them later on the computer, I failed to identify all the images correctly. To my recalcitrant brain, with its unusually weak visual recognition skills, three of the six gates were somehow indistinguishable. So we took another round. Frustrated with my deficiencies in visual memory, I digitally pasted my photographs into a document with notes on each gate, cramming my geography lessons.

I knew that however irrelevant the now perpetually open gates seemed today, the life of the qasba had once been channeled through them. I knew I needed to get the layout of Jahazpur. People and their stories, true and mythic, have always been my most passionate ethnographic calling. As such they trump not just architecture but politics, economics, institutions, and theory. This is not to say that I deny the many ways material and invisible structures of power condition the human tales I gather; it is rather a question of what takes precedence in my writing, and in my fieldwork practice too. I was pleased to see a monkey striding along the top of Hanuman Gate, an entry named for a nearby temple dedicated to Hanuman, the monkey deity beloved as Lord Rama’s loyal companion.

I lead readers into Shiptown (aka Sacrifice City) via five gates and a window. I present these entrances as specific, named, located, visible, solid structures. Equally I use them metonymically as contiguous with particular themes and topics running through this book. Each physical gate offers passages in two directions. Each metonymical gate stretches into key elements of my ethnography and may equally be taken as double-faced in that it intentionally links the world of Jahazpur, as far as I was able to participate in or learn about it, with the world of anthropology and South Asian studies, in which I dwell professionally and intellectually.7

Walls, gates, and windows are comforting frames, providing simultaneously apprehensions of containment/protection and access/visibility. The gates are inarguably emblematic of the place Jahazpur, and I deploy each gate to open up one or a set of related themes that readers will encounter in Shiptown. The matchup of gate to theme or subject, as sketched here, is inevitably loose. Nonetheless, I propose that the suggestive affinities are strong enough to sustain a set of topics central to this book and thus to suggest to readers particular kinds of passage.

None of the six built gates or the six conceptual pathways to and from Shiptown posed here is exactly congruent with the content of the six chapters to follow. However, the introductory sections, or entries, that comprise the remainder of Chapter 2 will resonate most strongly in specific additional chapters (as indicated parenthetically below, with the fullest convergence listed first):

1. Royal Gate (Bhanvarkala Gate): Commercial passages (Chapters 8, 4)

2. Delhi Gate: Historical passages (Chapters 5, 4)

3. Bindi Gate: Sociological passages (Chapters 4, 5)

4. Mosque Gate: Pluralistic passages (Chapters 4, 8)

5. Hanuman Gate: Ecological passages (Chapter 6)

5½. Window Gate: Ethnographic passages (Chapters 3, 7)

Those larger themes suggested by passages through the gates are woven throughout the whole text of this book as they are woven throughout life in Jahazpur. All of them characterize aspects of passages between rural and urban lives and livelihoods—this book’s overarching and underlying subject.

Walls no longer contain the place called Jahazpur, if they ever did. Of the chapters to follow not a single one takes place only inside the walls, and three are set almost totally outside them. And yet, the walled qasba is Jahazpur. Nor was Bhoju mistaken in giving significance to the gates. As is frequently the case, I am following his lead or am propelled on my way by his polite push from behind.

Royal Gate: Commercial Passages

In many regions of the world and many eras of human history, gateways carry a set of meanings related to political, economic, and cosmological power. Paul Wheatley’s magnum opus on Asian cities names Rajasthan’s capital Jaipur, a city of very imposing gates, as one of the most recent examples of cosmos-replicating town planning (1971:440). Wheatley writes: “The city gates, where power generated at the axis mundi flowed out from the confines of the ceremonial complex towards the cardinal points of the compass, possessed a heightened symbolic significance which, in virtually all Asian urban traditions, was expressed in massive constructions whose size far exceeded that necessary for the performance of their mundane functions of granting access and affording defense” (1971:435). It is unlikely that Jahazpur was designed to replicate the cosmos. Still, it is reasonable to conclude that the inspiration for the size and shape of Jahazpur’s Royal Gate was found in one or another of the region’s grander urban spaces. And it is indisputably the case that processions both sacred and secular regularly pass through Royal Gate, making an impressive sight even in the twenty-first century. Surely these processions with their clamorous if temporary claims on public space draw upon that ancient symbolic resonance.

A literal translation for the name of the gate I am calling “Royal” cannot readily be extracted from the Rajasthani-Hindi dictionary. According to Bhoju, Bhavarkala in the local language might awkwardly be rendered into English, putting the pieces together, as the “King’s Grandson’s Big Gate.” When I proposed “Royal” as a convenient gloss, he agreed with some relief, averring that it made perfect sense. Royal Gate’s name is the same as the name of the nearby water reservoir (talab) which has town-wide uses both practical and ritual—the latter including the bathing of gods every Jal Jhulani Gyaras (Jahazpur’s most ambitious and spectacular Hindu festival; see Chapter 4).

Royal Gate is the largest of the gates, so large that within its structure, set into each side of the passageway, are two venerable bangle shops. Commerce, which is the raison d’être of the qasba, thus insinuates its presence into the majesty of the gate itself. Jahazpur’s Royal Gate sees a constant two-way flow of people, animals, handcarts, and motor vehicles. On one side of this massive structure is the bus stand with its constant bustle of noisy ordered chaos. On the other side is the main market. If after entering you veer to the right, you will immediately arrive in Chameli Market, where Muslim-run businesses including meat, fish, and cotton quilts are clustered near the smaller of Jahazpur’s mosques, known as Takiya Mosque.8 Or you can wend more or less directly through the main market, eventually to reach Delhi Gate and pass through to the fenced, open parklike square known as Nau Chauk (discussed below). If you did not stop to chat, browse, or shop—which honestly never happens—you could easily walk the distance between Royal and Delhi Gates, or between the bus stand and Nau Chauk, in about ten minutes.

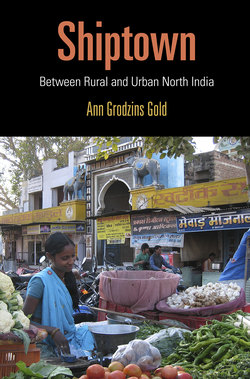

Figure 6. Looking outward from market to bus stand through Royal Gate, 2015.

Jahazpur’s main market is utterly crammed with shops; the shops themselves are equally crammed with goods. Whether you are in the street or inside a shop there is a feeling of tightness, density, and abundance of merchandise. Perhaps most common are the grocery stores (kirane ki dukan), followed by unstitched cloth, and increasingly popular (although largely for men and children) ready-made clothing. But the market also holds, in random order: shoe stores, photo studios, cookware, toys, electronics, sweets, gold and silver ornaments, stationery and school supplies, a dairy, plastic utensils, “fancy” (cosmetics, bangles, costume jewelry, and other trinkets and finery), supplies for festivals and rituals, and a lot more. There are barbers and tailors, for example, trading in services rather than goods. With just a few exceptions, any and all of life’s everyday necessities as well as its pleasures, comforts, and minor entertainments may be obtained inside the walls. There are no restaurants, but the largest sweet shop has a few tables. There is no cinema, but to my amazement, late in my stay, I was led down a few steps into a videogame parlor, a site I had passed countless times but simply never seen. I have noted just one pharmacy inside the market; the rest are conveniently lined up in a row near the hospital, which is down the road that leads to Santosh Nagar well beyond the bus stand and far outside the walls.

Between the two sides of Royal Gate, the bus stand, and the market, there is both continuity of merchandise and contrasts. Besides transport, the central and most vital feature of Jahazpur bus stand’s central space is the produce market; this space houses the vast majority of stalls conducting a flourishing produce trade—a wide variety of fresh fruits and vegetables in season. Some of the same items are available from small, individual gardener-vendors at the other end of the market, outside Delhi Gate at Nau Chauk. None of the grocery stores inside the walls sells fresh produce, although they do deal in garlic, onions, chilies, and other spices.

Outside Royal Gate at the bus stand we encounter, appropriately for a transport hub, various ways that the town of Jahazpur is hooked into the world around it. Obvious are those actual moving vehicles—buses, trucks, jeeps, and cars for hire—absorbing and disgorging passengers. Ever increasing in number are parked motorcycles, still the vehicle of choice for men with jobs or businesses that have endowed them with middle-class status but whose means are still limited.9 A car is not simply a one-time investment of capital; to drive one regularly requires outlays for petrol that far outstrip the cost of running a motorcycle. Nonetheless, private cars are also multiplying in numbers, and an automobile showroom was the latest business to arrive in the town some years after my fieldwork time.

The Hotel Prakash with its colorful facade stands out on one side of the bus stand. I understand decent, simple accommodations may be had there, but I never did enter its premises. There are places at the bus stand where you can eat a cooked meal, but they are not considered to be proper restaurants. Rather they are dhabas (roadside eateries), in that they have no menus and, like the Hotel Prakash, would rarely if ever be patronized by women or families.10 Another flourishing business is the fully stuffed “tent house” which rents out all the requisite hospitality accoutrements for a wedding or funeral feast, including the tent itself, cookware, and bedding for guests. There is a jam-packed store I privately called the “everything” store, where soap, toothpaste, vitamins, padlocks, cookies, undershirts, socks, and countless other useful items may be acquired, although you must know what you need and ask for it.

Ranged around the bus stand’s periphery are the high-speed Internet place, the bank, the cash machines (two of them), and several mobile phone recharge shops also offering fax services and other forms of telecommunication. (Some dispensers of similar services are also found in the interior market.) Also located at the bus stand, doing business with Jahazpur residents and villagers, are agents selling insurance, notable because their shops appear strangely vacant in contrast to the densely packed merchandise on display in most stores. Insurance, however invisible, sells.

One of the town’s oldest sweet shops, where we often purchased our favorite “milk cakes,” is located there. Next to the sweet shop is a paan stall; its owner reminisced about bygone days when lengthy lines of customers waited patiently to savor his special betel leaf concoctions. Now they may prefer to purchase inferior prepackaged substitutes at a far lower cost, lacking flavor, complexity, and art. Fried snacks including delicious kachoris are available at the bus stand. In the hot season there is a sugar-cane juice press in constant operation, producing lovely frothy green drinks; next to it, run by the same family, a year-round stall features cigarettes and such. The shops at the bus stand in the vicinity of Royal Gate continue to expand. The municipality profits from opening up space for the construction of new stalls to house additional businesses; two rows were under way in 2011.

If everything described thus far could easily apply to hundreds or even thousands of small-town bus stands in South Asia (and likely other parts of the developing world as well), Jahazpur’s bus stand also has a distinctive landscape, tapping the town’s particular histories of devotion and struggle. These permanent sites and moveable events reflect pan-Indian as well as local traditions. The Tejaji shrine, dedicated to an epic regional hero-god with the power to cure snakebites, is located right here.11 The Ram Lila stage is set up here in advance of Dashera—the fall festival marking Lord Rama’s defeat of Ravana and his return with the rescued Sita to Ayodhya. Here the epic tale is performed for ten nights running.12 Devotional songs (bhajans) to Ramdevji are performed on the bright second of every lunar month (when the waxing moon is just a sliver).13 Every major procession taken out in Jahazpur, whether Hindu, Jain, Muslim, or secular (as well as most minor ones, and there are plenty of them), will at some point take a halt and congregate for a time at the bus stand—whether processing from an interior site to the water reservoir or from an outlying shrine passing into the market through Royal Gate (see Chapter 4).14

Figure 7. Vegetable market at bus stand showing Satya Narayan temple in background.

The Satya Narayan temple established by the Khatik community in the mid-1980s is perhaps the most potently evocative structure at Jahazpur bus stand, signaling as it does the shifts of changing times and presiding in certain ways over economic developments in Jahazpur as much as religious ones. The Khatiks traded in live animals destined to be butchered and sometimes were butchers; they have SC status. As I understand it (although the timing is approximate), the Khatiks acquired the land where the Satya Narayan temple stands, as well as adjacent property now housing lucrative shops, sometime in the 1970s, when they had used their block voting power to support a politician who, when successful, rewarded them with this land. At that time, of course, the land had less commercial value than it does today. It did not take long for the Khatik community to begin their transformative actions, sacred and secular, devotional and commercial—the establishment of the Satya Narayan temple and of the vegetable auction and associated market (Gold 2016).

Sometimes urban Jahazpur would surprise me by keeping a tradition I had imagined to be wholly rural. This could happen even at the bus stand, with its urban air uniting globalized commerce with village-bound transport. On the day of Makar Samkrant—the winter solstice according to the Hindu lunar calendar, which comes in early January—there are a number of regional traditions. The best known among these is kite flying, which happens all over North India and Pakistan. In rural Rajasthan, however, Samkrant is memorably a day on which individuals purchase bundles of fodder and spread it out for the cattle. This is said to provide merit to the donor. To me it had seemed a sweet and wholly rustic notion: giving cows a day off the hard work of grazing and letting them feast lazily. The beneficiaries of this tradition would be any settlement’s collective herd, so the donor of fodder does not favor their own animals even though theirs might be among the herd, and many people who do not own livestock still donate fodder. In Ghatiyali village, this pampering of skinny livestock takes place on the banks of the water reservoir, rather far from all habitations, a purely pastoral landscape.

I was unprepared on Samkrant morning to encounter urban vendors at Jahazpur bus stand throwing down heaps of carrots for the ill-behaved cows that hang around here. This surprised me, especially as on ordinary days these indolent, pesky creatures, well aware of their sacred status, or so it seems, were often roundly cursed and smacked smartly on the rump or even on the head (though never actually beaten) for helping themselves, uninvited, to some choice, ill-guarded produce. Vendors keep sticks handy expressly for this purpose. But on Makar Samkrant at Jahazpur bus stand, cows feasted on carrots willingly donated. I note this here not only for its being a sign of rural-urban synthesis but because it offers a lesson about change.

The bus stand has not always been the bus stand. Before 1978, when that transformation took place, this site I know as Jahazpur bus stand was, it seems, the site where every morning the herd of cows and buffalo owned by town residents assembled to be taken to graze by a collectively employed herdsman. In villages such as Ghatiyali this gathering place is exactly the spot where people donate fodder on Makar Samkrant. In Jahazpur, we may thus assume that cows have a historically, spatially, and ritually chartered right to be fed just here. Carrots, abundant at this season, are more accessible than fodder to vegetable vendors in town—businesspeople who value the idea of acquiring religious merit.

For those living inside the walls, it would be Royal Gate from which they would most commonly emerge to set forth on many kinds of errands to places near and distant. Royal Gate was my gate, too, through which I both approached and departed the qasba. When I turned homeward I would walk through the bus stand, down Santosh Nagar Road, past the fresh squeezed juice stand (also a Khatik innovation), the subdistrict offices, the hospital, the post office, the idgah, the graveyard, all the way to Santosh Nagar’s very last side street where I lived.

Delhi Gate and Nau Chauk: Historical Passages

Only one store among dozens of small grocery or provision shops carried large jars of Nescafé, which I personally consumed in shocking amounts. Dan and I discovered this store at the far end of the market, not far from Delhi Gate. At first it surprised me that such a well-stocked store would be at what I assumed was the lesser end of the bazaar. But it all depends on your position, perspective, and moment in history. A town’s spatial orientations shift and change not only over time but according to where one stands. Picture the qasba opening up inwardly from Delhi Gate, not Royal Gate. For some who live at that end of town, most probably it still does. In Jahazpur’s not-so-remote past, Delhi Gate was definitely not the tail of the market.

Suresh Sindhi gave a very general account of the shift in orientations of Jahazpur’s commercial and transportation life. He told us, “The people didn’t used even to come to the Royal Gate, because where the bus stand is now was jungle, and no one came there; besides that, in the evening the gate was closed. The bus stand used to be at Nau Chauk.” Just outside of Delhi Gate is the rectangular fenced clearing known as Nau Chauk. Nau chauk means “nine squares” or “nine markets” or perhaps “nine corners.” Today the space called Nau Chauk is a small park surrounded by shops. It is worth looking further into the history of this space, which is Jahazpur’s only town square. Once it was adjacent to almost all the local government offices. Once it was connected with the royal residences inside the walls. Once Nau Chauk, and not the current bus stand, was the site of the annual Ram Lila.

Delhi Gate offers passage to a complicated history of town rule, and its passage denotes shifting orientations of both power and place. Try to picture Jahazpur in an earlier era: imagine today’s bus stand nonexistent. Also nonexistent were the fruit market, the Satya Narayan temple, and Santosh Nagar colony. The road south from the bus stand to Santosh Nagar, which today is flanked with government offices and the small businesses that grow up around them, at that time led only to the Muslim graveyard, the adjoining idgah, and the jungle with its common-property grazing ground. All the town’s administrative functions were in and around Nau Chauk. Today only the Patwari (land revenue office), the Cooperative Bank, and a few other minor offices remain in the Nau Chauk vicinity.15

In 2010–11, the vegetable sellers who squatted on the periphery of Nau Chauk displayed notably less attractive produce than those who stood proudly behind proper (if movable) stalls at the bus stand. Nau Chauk itself was a far quieter place than the bus stand with far fewer vehicles. However, there are still some quality stores ranged around Nau Chauk, including an excellent “fancy” store favored by Bhoju’s daughters.

Our passage through Bindi Gate will lead us to some social structural aspects of qasba life; here I set Jahazpur town in broader currents of Rajasthan histories. In the flat lands of Jahazpur are several Hindu temples that town citizens declare to be “very old.” Inside the walls is Juna Char Bhuja (“ancient Four-Arms,” that is, Vishnu); outside are Barah Devra (“Twelve Temples”) beyond Hanuman Gate; and Narsinghdwara (“Door of the Man-Lion,” again an avatar of Vishnu) on the banks of the Nagdi River. I have heard all of these attributed to the eleventh or twelfth centuries, but I have no documentation of their age. There is significant archaeological evidence of an ancient Jain presence in this region, dating to a period well before the Mughuls (Chattopadhyaya 1994:47; Sethia 2003:25; see also Chapter 5).

From recorded history, we know that in the second half of the fifteenth century, Kshetra Singh of Mewar (ruled 1364–82) conquered Jahazpur along with Mandalgarh and Ajmer, taking it from the Pathans and annexing it to Mewar (Purohit 1938:69). Jahazpur’s hilltop fort was among many that were built during an immense fortification project for the expanding kingdom of Mewar undertaken by Maharana Kumbha (ruled 1433–68) in the mid-fifteenth century (Hooja 2006:341–47; Purohit 1938:66).16 In the sixteenth century Jahazpur came under Mughal rule but not for long. Documented sources report that the emperor Akbar gave Jahazpur to Maharana Pratap’s rebellious half-brother Jagmal after the death of their father Udai Singh (Hooja 2006:466). This would have been just following the time period when Yagyapur became Jahazpur and when some local groups converted to Islam.

Jahazpur’s fort was captured by the small neighboring kingdom of Shahpura in the early eighteenth century and recaptured by Mewar about a hundred years later (Dāngī 2002). According to Purohit (1938), during the Maratta rebellion Jahazpur was for some time under the domination of Jhala Zalim Singh of Kota. Except for those relatively brief interludes between the Mughals and Independence, Jahazpur qasba and its surrounding farmlands remained under Mewar. Jahazpur’s last deputized local ruler, Vijay Pratap Singh, died in 1931 (some say he was murdered).

From chasing such slight references to Jahazpur as may be gleaned from history books, old gazetteers, and district census handbooks, the impression I have is that among the capitals from which Jahazpur was governed, only Shahpura was nearby, and Shahpura was too small to hold on to it. The capital of Rajputana’s preeminent kingdom, Mewar, within which Jahazpur was most often included, was at a considerable distance. Even in 2011, when I traveled by car from Jahazpur to Udaipur for a conference, I was struck by the distance, compounded by a very poor road for a significant stretch of the journey. I thought a lot on that trip about how far this distance might have seemed in the times of the Ranas.

Although it was certainly a pawn in royal doings for many centuries, my conjecture is that Jahazpur, intermittently but for lengthy periods of history, flew largely under the radar of rulers in any capital. There were for example wild fluctuations in revenue collection (Sehgal 1975:53). Because of the large Mina population in the region, this was never an easy place to rule. Minas were by reputation fiercely independent and powerful fighters. Sometimes they served whoever was ruling but just as often effectively defied impositions (taxes, conscriptions) from any outside power. Tellingly, when Colonel Tod visited in 1818 it was Minas who greeted him (see Chapter 5). It may well have been a matter of little regret for a ruler to hand off Jahazpur to someone else, as Akbar did to Jagmal. It is also advisable in considering Jahazpur history to take into account that dominant communities in Jahazpur qasba proper were never Rajput and were concerned with trade, not war. No matter who was ruling, opportunities to buy and sell would be ongoing.17

In 1997 I recorded, in Ghatiyali, Sukhdevji Gujar’s memories. The most critical juncture of his young adult life took place in the early 1940s and involved Jahazpur’s Nau Chauk. It was there that he went to enlist in the army. He walked thirty-three kilometers alone in the night, from Ghatiyali to Jahazpur. He told me:

I wasn’t afraid of anything, and nothing attacked me! I didn’t meet anyone at all, I went on foot. [To walk alone in the night requires a lot of courage.] In Jahazpur, at the place called Nau Chauk, people were enlisting in the military; in the middle of the city.

There were hundreds of people there, who had come in order to enlist…. carpenters, gardeners, ironworkers, Minas, Rajputs, lots of people, all the jatis. And a gentleman came, a fair-skinned gentleman, an Englishman. There was just one: “Duke Sahab” [presumably a British military officer]. He arrived, sitting on a horse, and wearing a hat on his head…. People were lined up there in rows, three by three, and the gentleman walked in-between the rows, looking, looking. And then he put a mark on me.

And the ones who had marks, they took them over to one side, so they put me on one side with them. On that day, in one day, in the same fashion, 150 people were selected; out of many hundreds who wanted to enlist. (Gold and Gujar 2002:168–69, condensed and slightly reworded)

Sukhdevji’s memory is evidence that in late colonial times, during World War II, Nau Chauk had its official functions and was put to use by the British, in spite of Jahazpur being part of Mewar and governed under paramountcy rather than direct rule. I imagine Duke Sahab would have taken permission from the Rana in Udaipur to use Nau Chauk in Jahazpur as a recruitment site, but that is pure speculation. I do know with certainty that Nau Chauk and much that lies in its vicinity is intimately connected with the checkered history of rule in Jahazpur.

Adjacent to Nau Chauk is a building that is now Jahazpur’s overflowing upper secondary school. The school building is grafted onto a former royal residence in an architecturally odd fusion. On the grounds of the school or former palace is a large, gated shrine to the Hindu deity Ganesh, which everyone knows as a place where a powerful authority once sat, whether it was Jahangir, Shah Jahan, or the delegated royal agent for this area (hakim). Ram Swarup Chipa, for example, told us that Ganesh’s place was once a meeting hall built by Jahangir. Another Hindu man from an artisan community speculated for us that Hindus had installed Ganesh there in order to claim it for themselves, as a preemptive move against Muslim ownership.

However, a Muslim interviewee told us explicitly that Ganeshji was put there deliberately by a Mughal ruler to ensure that no ordinary mortal being could ever sit on the same spot where the emperor had held court. A different Muslim interviewee had told us in 2008, “Shah Jahan was sitting where Ganesh is now. He thought, ‘after me, no one can sit on my chair,’ so he himself installed the Ganesh image.” Shravan Patriya, a Brahmin journalist, told us that Ganesh was installed in this courtyard “to keep the place pure.” In all its variations, the installation of Ganesh would seem to mark an amiable delegation of power from Muslims back to Hindus in Jahazpur’s past.

A number of persons from different communities referred to Nau Chauk in interviews as a site of significance to the history of the town, or of their own families and trades. Some further tidbits about Nau Chauk are compelling.

Kailash, whose caste identity was wine seller (although this was not his current business) told us that the liquor storehouse maintained by his community had been located in Nau Chauk. To measure out the liquor, he said, “they used a little brass pot, and distributed it straight from a small storage tank.” He told us that his great-aunt would “measure out liquor with the brass pot and sell it there.”18 Another man, from the leather-working community, spoke of his grandfather who was a “tantric magician.” Once, one of the great kings of Udaipur came to Jahazpur and summoned our interviewee’s grandfather, demanding that he perform his magical arts. Where did this take place? In Nau Chauk. The man asserted that his grandfather did not disappoint the king; he took a broom and transformed each one of its straws into scorpions.

As they piled up, Nau Chauk stories began to remind me of Bob Dylan’s Highway 61—an ironic venue for every kind of weird, game-changing performance in the history of humankind. Even today, many ritually significant events take place at Nau Chauk. The taziya, symbolic tomb of heroic martyrs whose deaths were a turning point in Islamic history, spends the entire night on the edge of Nau Chauk, before both annual Muharram processions (separated by forty days). Although Jahazpur had many Holi fires in many different neighborhoods, a major Holi effigy is staked and burned at Nau Chauk. This was the only Holi where I saw a Brahmin priest perform a worship ritual before igniting the demoness wreathed in firecrackers. On both Hindu and Muslim festivals, demonstrations of physical prowess, commonly called akara by both religious communities, took place at Nau Chauk.

Figure 8. Children drum at Nau Chauk on Muharram procession morning.

Note well that these things do not happen inside the fenced square, although presumably Sukh Devji’s recruitment into the British Army did. All the other events of public import described here take place around the edge of that park. The actual space within the square offers another complicated story from recent times of which I am certainly missing some key elements, but which nonetheless I shall attempt to sketch. The fenced center of Nau Chauk was somewhat unkempt during most of my fieldwork. There were some trees and other greenery including flowering vines inside, but the ground was dry and brown and the space unattractive. Sometime in 2011 all that began to change. While I was still living there the town chairman (mayor), influenced doubtless by some patronage group, had the interior spruced up and planted with flowers. He had a decorative fountain and a stone lion’s head on a pillar installed there. Later a cardboard image of Maharana Pratap (ruled Mewar 1572–97) appeared.

Over a year after I departed, a proper stone statue of Maharana Pratap was installed inside Nau Chauk with festive pomp including rains of rose petals. Although locals such as Bhoju Ram were drawn to participate, the event organizers and sponsors were part of a statewide organization of Rajput patriots; few hailed from Jahazpur where, as already noted, Rajput power has thoroughly dwindled. The entire transformative process was marred (I heard after the fact) by minor but prickly “communal” incidents expressive of rancor. These included small vandalisms to the new fence followed by disputes over who would pay the cost of repair for said vandalisms.

I confess that Maharana Pratap, as an icon of Rajasthan’s glorious martial history, has never warmed my heart. I would prefer to refuse ethnographic responsibility for reporting on a development that happened, after all, more than a year beyond my fieldwork’s conclusion. But there are two things I must add to update my account of Nau Chauk. First, on my most recent visit in 2015 the space inside the fence was very nicely maintained, with green grass and colorful flowers pleasing to the eye. Yet it is hardly a public park in the Euro-American sense, designated for democratized enjoyment of its pleasant features. Nau Chauk is fenced and the gate kept locked. Second, in spite of the local Muslim community’s objection to the statue, and Hindu rebuttals, there has been a kind of reconciliation, at least on the surface. The taziya continues to spend the nights before Muharram in its usual place near the small park with its new statue. For the time being, Jahazpur’s inner spirit of “live and let live” prevails.

Bindi Gate: Sociological Passages

In late August 2010, well before my systematic tour of the gates, Bhoju and I made our first foray into the leather workers’ neighborhood inside the walls.

Then we drove through Bindi Gate and into the Regar mohalla, where firewood is stacked in huge piles, where fans don’t run, where I sweated for the hour of the interview. There was arati [ritual of circling lights before an image] going on at the Ram Devji temple, and the children crowded round me in an amazingly non-Jahazpur way, more like village children. The arati was extensive and beautiful; I took pictures, the children wanted to be in the pictures and nearly wrenched the camera from my hand in their excitement to see themselves in the small screen.

Then we want to the home of a Regar teacher whose old father talked to us. I appreciated the respect the younger man gave to the older, letting his father’s interview finish, before he began speaking to us with eloquence about the disadvantages faced by his community, even in recent years: the slights they suffered in schools, as workers, when bridegrooms go to villages, at tea stalls, and worst of all the story of the Ambedkar statue purchased 6 years ago but not yet installed due to high caste objections.19 (field journal, 29 August 2010)

Bindi Gate may be the most dilapidated of the old doorways, and its part of town feels the most “villagey,” as my journal exclaims. Children are more numerous and more of them are wearing torn T-shirts, while few dress in the ornate, costly jeans favored by the qasba’s middle-class youth. The Regar children’s excited behavior was likely indicative of less training in the disciplines of the schoolroom, where the first lesson taught is how to sit, that is, how to submit their small bodies to an ideal of order (doubtless inherited from the British; see Kumar 2007:25–48).

When I initially inquired what the name “Bindi” signified, people told me that the gate once led to a village called Bindi that “no longer existed.” As it turns out, Bindi village still does exist in Jahazpur tehsil (subdistrict). The 2011 Census records it as inhabited by seventeen families with a population that is 94 percent Scheduled Tribe.20 Although Bindi is not numbered among the twelve hamlets incorporated into Jahazpur municipality, it shares with them a preponderant Mina identity. Yet not that long ago, before Independence when Jahazpur belonged to Mewar, Bindi was a “revenue village,” defined as an administrative unit of the smallest order. At that time, members of the ruling Rajput community lived there, doubtless in order to collect taxes and perform other low-level administrative functions. Even in its heyday, and despite its giving its name to one of the three qasba gates to the exterior, I suspect we might safely presume that Bindi was never a plum posting.

Looking out from Bindi Gate you can see the old fort on the hilltop. Turning inward you find that those neighborhoods nearest to this gate belonged to leather workers (SC), lathe-turning woodworkers, and boatmen (the latter both categorized OBC, “other backward classes”). Among these communities, unlike the former butchers with their reputation of collective improvement, it seems only a few of their members have prospered in these changing times.

The Kir (boatmen) keep boats in their street as emblems of identity (and these are still in occasional seasonal use as for harvesting water chestnuts). Kewat is their dignified caste name, after the fabled boatman from the Ramayana epic who took Ram, Sita, and Lakshman across the river when the three divine beings made their way from the palace of Ayodhya to their fated forest exile. New bridges and dams combined with draught would be the main combined causes of decline for the traditional work of boatmen. The lathe-turning carpenters (Kairathi) have seen their business markedly dwindle with the lowered demand for wooden implements, including toys, for which the town of Jahazpur was once well known (Census of India 1994). Several Kairathi families moved away from Jahazpur, having sold their homes to Sindhi merchants who now populate their neighborhood, I was told. In 2011 there were just two active Kairathi workshops infused with the sense of an accomplished yet moribund artisan identity. I say moribund because fathers deliberately were not apprenticing their sons but rather devoting familial resources to training the new generation for alternative careers.

Leather workers retain neither mementos (as the Kir do their boats) nor active workshops (as the Kairathi still possess) that would bring to mind their own stigmatizing past work of tanning hides. Many have gone into construction. A fair number of leather workers are government servants and have ascended to middle-class status, at least economically. Affirmative action (called “reservations” in India) supports higher percentages of government service jobs for members of SC communities, but some appear more able to find advantage in these programs than others. I found, when interviewing persons close to the bottom of the old ritual caste hierarchy, expressions of gratification that much had indeed changed, and simultaneously of anger that change was maddeningly incomplete.

This is not a book about social organization, social hierarchy, or power. I will not make a list of all the castes that live in Jahazpur, nor could I with total accuracy even if I wished to do so. No chapter here is devoted to compiling or analyzing the many statements about social hierarchy that in fact I did record. Mostly I recorded them because Bhoju Ram, who assisted in about two-thirds of my interviews, inserted into most of them routinely, and without my ever requesting that he do so, one or more queries about caste. I privately brooded over what seemed to me to be his tiresome fascination, or his old-fashioned sense of what might be significant. References to caste in the interviews would have been far fewer had I been the only one asking questions. In my interviews with women, where I controlled the lines of inquiry, there is almost nothing about the birth-given social hierarchy. When the conversation departed, as it often would, from my own directed interests it followed theirs: domestic politics, neighborhood quarrels, food.

Sumit Guha has recently suggested that “caste’s religious strand has frayed away but the one binding it to the exercise of power is thicker than ever” (Guha 2013:211). Guha and others see caste today as something akin to ethnicity. I appreciate that turn in the recent literature on India’s social hierarchy. Basically it lays stress on inherited identity as it infuses sense of self and as it is used instrumentally in relation to others both politically and professionally. Such active uses of birth-given identity or rank certainly are among the circumstances of life in contemporary Jahazpur.

Bhoju is my collaborative research partner, not an assistant paid only to do my bidding. I therefore held my tongue and respected his interests. Indeed I thought it might represent an integral feature of the village-to-town transition that I seek to highlight in these pages that Bhoju, himself a participant in that transition, thought in terms of caste when living in a place where it had genuinely lost certain kinds of salience. People in Jahazpur readily, and for the most part unhesitatingly, respond to questions framed in a language of caste with answers similarly framed. It is not that the caste framework had become alien to them. But it is, I would argue, not their first way of looking at things. Only very rarely did an interviewee initiate this topic.

Throughout this book I make observations using the language of caste. When I write in Chapter 3 about Santosh Nagar, I talk about a Brahmin woman and her status as a self-proclaimed ritual expert, often but not always valued by the women from agricultural communities who predominated in the groups that gathered around her at collective rituals. When I write about processions in Chapter 4, I speak of the leather workers’ struggle to be included in the Jal Jhulani parade and the rather anticlimactic if satisfying result: normalization of their participation (as if the resistance had been more knee-jerk than of any heartfelt discriminatory depths). When I write about the market in Chapter 8 I emphasize roles played by former butchers and former wine sellers, and it seems to matter who they are “by caste.” Caste identity literally leaps out at a stranger; here as throughout much of Rajasthan, caste names are used as last names, including Gujar, Khatik, Kir, Mina, Regar, Vaishnav, and so forth (see Pandey 2013:208–10). But caste is not the dominant subject of my book, and I would venture further to argue that caste is not the dominant subject of life in contemporary Jahazpur.21

Bindi Gate, by evoking the old revenue village and the contemporary struggles of leather workers, carpenters, and boatmen, leads us in two directions: outward to the fiscal bindings of town with larger units of governance including taxes and benefits for the poor; inward to the intersections and interactions of discrete but variously integrated communities, to the histories of political and ritual struggles for power and dignity, and to the ways that governance enables, obstructs, or ignores these struggles.

Mosque Gate: Pluralistic Passages

An archway traditionally bestows honor and respect, creating a passage simultaneously conferring and confirming status. We see this easily in the plentitude of temporary cloth arches set up to welcome the Ram Lila procession, a distinguished visitor, or a wedding party. Mosque Gate is an internal gate. It never served to segregate the Muslim population but rather to mark a sacred area before the doorway to the mosque and thus to set apart and to honor the mosque itself.22

We learned from Mahavir Singh (one of just two Rajput interviewees) that long ago the Rajput neighborhood also had an arched gateway, as did a few other neighborhoods belonging to more important merchant and Brahmin lineages. With the decline of residents most invested in maintaining them, these structures had been torn down when it became expedient to make way for additional construction of more useful edifices. Small but vividly blue, Mosque Gate, in contrast, was in fine condition during my stay in 2010–11. On revisits, I noted that the old deep blue gate I had always thought very attractive had been allowed to deteriorate, while an imposing, tall, new Masjid Gate of stone blocks was constructed.

A number of persons, when pressed to list the characteristics of a qasba during both recorded interviews and casual conversations, would begin with a single defining attribute: diversity. This comprised a multiplicity of castes and secondarily of religions. One of the hallmarks of urbanization is diversity; and with diversity arrives the necessity of pluralism. This observation would certainly be deemed a truism in urban studies. However, here I follow the lead of Gérard Fussman, who codirected an Indo-French collaborative investigation of history and culture in Chanderi, a qasba in Madhya Pradesh state. Nearly the same size as Jahazpur, Chanderi, like Jahazpur, has a mixed population of Hindus, Muslims, and Jains. I summarize Fussman’s points in a condensed paraphrase: The passage between a village population and a town population entails a veritable rupture corresponding to the transformation from a population which is relatively homogeneous and an economy which is essentially pastoral or agricultural, to a population and an economy which have become much more diversified, and where commerce, manufacturing and political-administrative functions all play roles of more or less increased importance (Fussman et al. 2003, vol. 1, 67). Places such as Jahazpur, and other North Indian qasbas including Chanderi, present this “veritable rupture” on a smallish scale and thus perhaps with particular vividness. Just to run your eyes over the styles of clothing visible at Jahazpur’s busy bus stand, or worn by those peopling its crowded market streets, is to observe a diversity that is locally so run-of-the-mill as to attract no notice whatsoever.

Only the foreign outsider finds the scene striking and wonders at the proximities of men in Western shirts and pants, some bareheaded, some capped; some bearded, some clean-shaven; other men in dhotis or kurta pajamas, some heads adorned with Rajasthan’s characteristically bright red or multicolored turbans. Women’s dress also varies by class and age and religion: some in saris, many in long skirts and blouses covered by the Rajasthani orhni or “wrap”; many in kamiz-salwar, which are worn by Muslim women of all ages and among Hindus and Jains by younger, unmarried teens or young women returned to visit their natal homes; a sprinkling of upper-class teenage girls in stylishly fitted jeans and T-shirts. The latter reflects not just urbanization but the influence of television. Most adult females still keep their heads covered, but it is not uncommon to observe a few on any given day who are bareheaded, and readily to conclude they might be teachers, or perhaps visitors from a larger city, NGO workers, or representatives of local, regional, or state government.

Thus a visible everyday mix encompasses rural/urban; Hindu/Muslim; and an array of differences in caste, class, and profession. Do these differences play out in mutual engagement and enrichment, or in fissure, abhorrence, and violence? Throughout most of Jahazpur’s history, it has been the former. The plural nature of Jahazpur was one of the reasons I was drawn to study it. Jain families, here as elsewhere, are successful in business and influential in local politics. Jains add to the diversity of the qasba, but it is the large Muslim population that distinguishes Jahazpur from most Rajasthan towns. As is the case throughout Rajasthan, Hindus are the majority in Jahazpur. But whereas in the state as a whole, Muslims average around 8 percent of the population, inside the walls in the oldest part of Jahazpur qasba I regularly heard estimates as high as 40–45 percent. In the 2011 Census data for Jahazpur municipality, the official breakdown is 73.05 percent Hindu; 25.39 percent Muslim, and 1.45 percent Jain. Given that the municipality includes the all-Mina twelve hamlets, these high estimates for the qasba itself are not terribly exaggerated.23

Mushirul Hasan, in his literary and historical study of qasba life in the eastern Uttar Pradesh region during the colonial era, particularly celebrates qasbati pluralism. He writes that in North Indian qasba culture, “Besides differences and distinctions there were also relationships and interactions…. The stress is therefore on … religious plurality as the reference point for harmonious living” (Hasan 2004:27, 31).

Jahazpur Muslims are divided into various groups, far from homogeneous in terms of ancestry, social class, attitudes, and reputed behaviors. The majority belong to a jati-like community called Deshvali or “of the land.”24 They are understood to be locals who converted to Islam in the Mughal period; many said this took place during the time of “Garib Navaz,” the famous Chishti Sufi saint of Ajmer who lived during Akbar’s reign.25 This conversion likely took place during that same era in which the name change, Yagyapur to Jahazpur, was inscribed.

In summer 2007 we interviewed a distinguished Muslim citizen of Jahazpur, who was then seventy-two years old. Bhoju asked him, “How many generations have you resided in Jahazpur?” He replied that his community had been there for six hundred years. He said that Muslims had not been in Jahazpur when it was first settled but came during the Mughal period, under the emperor Jahangir in 1602 CE. He estimated that eighteen or twenty generations of his family’s forefathers had lived in the town.

Both Hindus and Deshvali Muslims tended in interviews for the most part to downplay the differences between their respective communities’ practices and character. Both stressed shared roots, shared lineage names, shared cultural traditions, and a long-standing mutual regard.26 Middle-class Hindus often said of Deshvali Muslims: they are “like us.”27 If asked to elaborate, they pointed to two factors: landownership and parallel customs.28 (For example, before a wedding among Hindus the first invitation goes to Ganesh; among Muslims it goes to the saint, Garib Navaz. Thus, in both cases, the invitation initiating an auspicious event goes to an enshrined and revered persona—as both Hindu and Muslim interviewees explicitly noted.) Of course Hindu and Muslim interviewees did emphasize evident noncontentious distinctions such as festivals celebrated or the ramifications of internal divisions (or lack thereof).

A class factor entailed by “sameness” discourse is evident.29 When middle-class Hindus say that Deshvali Muslims are “like us,” they mean they are solid, propertied citizens, businessmen, and people with an obvious stake in the peaceful and prosperous life of qasba trade. The category Pardeshi Muslims is often contrasted to Deshvali in essentializing discourse: they are viewed as rootless potential troublemakers lacking stable sources of livelihood. The propertied versus indigent divide does not in reality align with the Deshvali/Pardeshi distinction, however. Among the Pardeshi Muslims are families possessing considerable land both inside and outside the walls. Some Pathan families were historically a kind of nobility whose ancestors probably played roles under Muslim rule similar in function to Rajput hakim under Hindu kings. Other Pardeshis are of a lower economic status. An example often given to me in this regard was that Pardeshi women roll bidis (locally made cigarettes) for a living; there were always a few such women sitting on the street visibly engaged in exactly that work. But certainly not all of Pardeshi Muslims are poor. Neighborhood is another factor used to classify Muslims prone to disruptive behavior. I heard it said again and again that the Muslims who live around the crossroads known as Char Hathari (“four markets”) are unruly and quicktempered, spoiling for a fight, so to speak. Yet both Hindus and Muslims often testified—Hindus ruefully and Muslims proudly—that all Muslims have a special unity within religious contexts: they eat and pray and vote together, although the different Muslim communities do not intermarry.

One Hindu man, Bhairu Lal Lakhara, explained to us why Hindus are disadvantaged by the unity of Muslims. Although the similes he employed (“Hindus are like dogs but Muslims are like pigeons”) were unique within my interviews, the ideas expressed—that Hindu unity suffers from multiple fissures because of caste divides, but Muslims are all for one and one for all—were extremely common and often expressed by Hindus and Muslims alike. Bhairu Lal had a way with words and spared no one in his social commentary; he is the same person who defined the middle class to me as a “camel’s fart” hanging between the sky of wealth and the earth of poverty. Here is how he characterized the difference in unity between Hindus and Muslims:

Muslims just say Bishmillah [“in the name of God”], and then eat together. And if you fight with one Muslim, then ten more will come to support him. But among us [Hindus], people will say: “That’s a Mali, that’s a Brahmin, that’s a Gujar, that’s a Kir, that’s a Carpenter,” so no one will come to your aid. The Butchers are separate; the Sweepers are separate. But they [Muslims] have unity. Hindus are like a pack of dogs; if you throw them one piece of bread, they will fight each other over it, and even kill each other. Muslims are like pigeons: if you throw a handful of grain, they all will peck it together.

[Bhoju Ram for my benefit, spelled it out even more clearly: “The dogs would rather lose the bread and kill each other; but the pigeons happily share.”]

Muslims, in spite of belonging to named groups that operate very much like Hindu jatis in terms of marriage, replicated this discourse of their superior unity and egalitarianism in the context of religion.

For example, Sariph Mohammad Deshvali—a dignified, successful businessman in his prime—discussed internal differences among Muslims with Bhoju Ram and me. Bhoju put to him a question about Pardeshi Muslims, asking Sariph if the Deshvalis transacted “daughters and feasts” with them: that is: did they intermarry and did they co-dine?30 Sariph answered without hesitation: “Not daughters, but we do share food.” He spent a fair amount of time telling us about the different Pardeshi communities, all of whom, like the Deshvali, are endogamous.

Then, spontaneously (that is, without any prodding from either me or Bhoju), Sariph went on at length to emphasize lack of discrimination among Muslims at religious events.

When people are praying, there is no difference, all the Muslims are together. At Id [for example] the time for prayer is fixed for 1:30 and everyone will be standing; suppose the maulvi [esteemed scholar or teacher] comes a minute late, he can’t go in front he has to stay behind, but if a poor person comes early he will stay in front; there is no special respect.

Once we were reading namaz, and a minister of the Rajasthan state government, a Muslim, came to join us, and he stood in the back. No one said “here is a minister.” Even though he was standing in the sun, no one took care to give him room. And he didn’t say anything either, he did not ask for room, for a place in shade. He stood there in the back, in the sun. There is no discrimination among persons.

What may divide Jahazpur Muslims (although this was in my presence rarely discussed) is religious orthodoxy, rigidity, or strictness—attributes wrapped up together in the Hindi word kattar. A number of persons from both communities used this word to describe certain Hindus as well as certain Muslims, but it was more often used for Muslims. The term kattar seems to hold implications of embracing global, acultural Islam, and stricter application of many rules. For example, I heard Deshvali Muslim women use it, disapprovingly, to refer to those Muslims who promoted stricter veiling practices.

Here is one usage supplied by a highly educated (Hindu) Mina man, who lived in a nice house outside one of the twelve hamlets but commuted quite some distance to teach college; he succinctly unites the two main elements of class and strict religion that people say make some Pardeshi Muslims prone to troublemaking: “The Deshvalis get along [with us] because their culture is like that of the Hindus and they have land and business (kheti dhandha), so they think about that. But the Pardeshi—they have neither land nor business, and they follow Islam very strictly [literally: “they are kattar”].”

Not long after the November festival (urs) of Jahazpur’s main Muslim saint, Gaji Pir, my husband and I went shopping for shoes. A bearded young shopkeeper we encountered on this excursion told me he had heard that I had attended the urs (word gets around, Jahazpur is village-like in that way). To my discomfiture, he lectured me (partially in Hindi and partially in passable English) on his views that such events were the culture (sanskriti, using not the English, but the Hindi term) of India and not “true Islam.” He told me he had personally stayed away from the urs, and that he preferred always to pray in the mosque. His views were not at all the norm in Jahazpur, I should emphasize. I bought the shoes but brooded over encountering such views unabashedly articulated in the heart of Jahazpur market.

Elsewhere in South Asia, some Islamic leaders have critiqued visits to saints.31 Yet all evidence showed the majority of Jahazpur’s Muslim community highly invested in the celebration of their miracle-working pir (A. Gold 2013). All other Muslims with whom I conversed, whether in an interview situation or casually, honored Gaji Pir with enthusiasm. Many loved to tell story after story about his miraculous boons.

I persuaded Bhoju (who was acutely sensitive to any potentially delicate or offensive topic when dealing with Muslims) to ask one Deshvali community leader, a professional educator, whether there were any Muslims in town who objected to the practice of revering the tombs of saints. He answered, emphatically, “There are no such people in Jahazpur; it is Jahazpur’s good fate [shobhagya, a Sanskrit word] that there are no such people here yet.” His “yet” (ab tak) reflected an awareness that elsewhere on the subcontinent this might not be the case and that Jahazpur itself might not be spared the arrival of these views.

Jahazpur is by and large a successfully plural place, with a strong Muslim community and an important multistranded sense of commonality among Hindus and Muslims in terms of possessing shared history and traditions as well as contemporary interests in keeping the peace. Among Shiptown’s thematic gateways, Mosque Gate stands for my conviction that Jahazpur qasba is a place where strongly held religious identities coexist not just in mutual tolerance but in mutual regard. It also stands for what Hasan and Roy (2005) call “living together separately.” The new Mosque Gate looks much like an Arabic gate and may speak of this separation in the language of stone. But it also speaks simply of community pride, of the urge to build and display one’s identity, which Jahazpur’s Muslims, Hindus, and Jains all have in common. Thus the imposing proud structure of New Mosque Gate and the egalitarian humility of the idgah may be held in one thought, as all of one piece.

Hanuman Gate: Ecological Passages

Hanuman Gate leads beyond Nau Chauk outside the qasba walls in the direction of Gautam Ashram, a retreat belonging to a Brahmin lineage used as a site for social and religious events. There, it is said, one can still see and decipher an inscription referring to the site as Yagyapur, although a painted signboard for the ashram normally obscures the old lettering. There is also an old temple to Hanuman here, accounting for the gate’s name. Not far from Hanuman Gate is a Muslim saint’s tomb, as well as a separate Muslim shrine of the type known as chilla—not a tomb but rather the location of a saintly person’s ascetic practices, especially fasting. Jahazpur’s chilla is dedicated to Gagaron Baba, whose well-known tomb in another city Bhoju and I had visited in 2006 (A. Gold 2013). The chilla’s wall and the ashram wall are contiguous. When Jahazpur’s chairman set out to redirect the gutters and keep sewage out of the Nagdi River, at least as it flowed through the town, objections made by the communities attached to the two sites were among the difficulties he encountered. The new gutters flowing with pollution would have to pass uncomfortably close to the boundaries of sacred sites—ashram and chilla—a situation ultimately ameliorated by the construction of a wall (see Chapter 6).

Hanuman Gate, through which Bhoju and I passed each time we were on our way to update the river’s ever-changing story, serves to evoke environmental issues. More than that, it evokes the unity of human life as bound, in an ever-fluctuating but permanent condition of mutual interdependency, to a geophysical and natural environment. Hanuman as divine monkey appropriately confuses nature/culture binaries and adds an element of uncalculated power (Lutgendorf 2007).

For about two months of my research time Bhoju and I obsessed together on the Nagdi River’s plight. It was definitely the longest (though not the sole) single-mindedly dedicated phase of my Jahazpur fieldwork. Yet I had never intended to study ecology in Jahazpur. The river itself was not on my agenda, nor was it in my line of sight when I began fieldwork. Because of the garbage I didn’t actually want to see it. We came upon the struggle to save the Nagdi in a roundabout way, through listening to tales of local politics. Years earlier, an interest in small-scale ecological successes effected by divine power brought me to Jahazpur. This was long before I had any interest whatsoever in urban ecologies writ large. On Jahazpur’s hilltops are two well-protected “sacred groves,” each surrounding a shrine, Hindu and Muslim, respectively. Malaji, a regional hero-god of the Hindu Mina community, is housed in a dazzling white temple. Near the fort is the revered tomb of Gaji Pir, a Muslim saint who was also a warrior, eyecatching with its glowing aquamarine wash. Jahazpur’s hilltop shrines are important sites of religious power and community which are lovingly tended.

Stories and practices associated with environments under divine protection offer some promise or potential for imagining benign relations with the natural world (Centre for Science and Environment 2003; Kent 2013; Gold 2010). Taken together, river and hills reveal the thoroughly interlocked nature of urban landscapes with twenty-first-century environmental issues. Hanuman, the monkey god, and the real monkeys that range through Jahazpur seem appropriate mascots for passages into and out from endangered ecologies.

Window Gate: Ethnographic Passages

Window Gate provides an apt metaphor for my own fieldwork practice, which often involved choosing those passages that were small, unheroic, without fanfare (as I never wished to call attention to myself).32 We found Window Gate only when directed there. No parades march through it, nor indeed could they.

How did I encounter Jahazpur? I recorded about 140 interviews. I took so many photographs I cannot even attempt to count them. I drank, by my estimate, more than fifteen hundred cups of tea at other people’s houses, not counting the tea we brewed at home. Anthropologists are consumers and contribute to the economy as well as fattening on sugary hospitality. Mostly, Daniel and I did our shopping in Jahazpur qasba. We patronized the fruit and vegetable vendors at the bus stand almost daily and bought supplies of spices, oil, sugar, raisins, and so forth from shops within the qasba. Soaps and toothpaste, bangles and braid holders, slip-on shoes for winter and rubber thong sandals for the rainy season, cough drops and vitamins galore, a shawl and a sweater and a cotton-stuffed quilt for winter, a cooler (our biggest market purchase) when the hot season rolled around. So many lemons, so much garlic, cases of soda water!

We subscribed to the Hindi Rajasthan Patrika with its Bhilwara District insert full of local color; it was delivered every morning along with a half kilogram of dairy milk. We hired a cook for a while. She was an angry young woman and eventually quit without warning (in spite of the whole neighborhood’s outspoken conviction that we overpaid her outrageously). But before she left she taught me some things I needed to know.

Sometimes the routine of fieldwork took second place to hospitality. We were visited by one of my graduate students whom everyone mistook for my son; to make matters more confusing he was followed not so many weeks later by my actual son with his fiancée (but we told everyone she was his wife); then my niece and great-niece; my husband’s two sisters and one brother-in-law; my younger son; and a whole busload of Syracuse students (who only stayed one afternoon). Thus we made a bit of an impression on Jahazpur; pretty much every female visitor, no matter what her age, was inappropriately dressed by Jahazpur lights.

For about the first eight months of my time in Jahazpur I felt so privileged, so lucky. Except for a terrible worry about my sister’s health that began in November, I was perfectly happy. Released from the classroom, from dull and dulling meetings, from all academic obligations—those are the things I was glad to be without. What was I glad to be with? First, to have Bhoju’s family around the corner, for they are like my family. Second, to have embarked on a vast project, taking me back to my dissertation research days when I lived in Ghatiyali; to know that anything that happened was worth writing down, that every conversation held gemlike glimmers of the unattainable whole; that even if I couldn’t keep perfectly straight who lived in which house and who was married to whose brother, I was nonetheless absorbing a whole new world of sociability.

My voice will not vanish from the chapters that follow. Window Gate opens into every chapter. For this introduction to my ethnographic practice, I need to say a little more about its collaborative nature and its composition. Over the past thirty years Bhoju and I have crafted, recrafted, and published accounts of an evolving relationship at once working and familial (Gujar and Gold 1992; Gold and Gujar 2002; Gold, Gujar, Gujar, and Gujar 2014). Although professional and familial motifs have intertwined in our relationship from the beginning, both in Bhoju’s mind and in my own the mode of our connectedness has increasingly become one of kinship. I am part of Bhoju’s family now as he is part of mine. Madhu and Chinu take these conditions for granted, having known me since birth as their paternal aunt (Buaji). In 2010–11 they too became graceful, part-time producers of ethnography (see Chapter 3).

How do we negotiate this odd union of kinship and research? I expect it sounds much harder than it is. Familial relatedness and intellectual relatedness have in common an intimacy and an interdependence that is at once psychological, emotional, cognitive. As family we exchange gifts, we worry about one another, we chide one another, we ask personal questions, we quarrel, we forgive. As research collaborators, we labor tediously to get details right and exalt in shared discoveries.

By his own account, Bhoju’s orientations to matters such as caste rules of commensality remained rooted in the rural community that had formed and nourished him and on which he still depended for crucial social solidarity. This led to some discomforts with our new research endeavor.33 It would go without saying that Bhoju’s experiences of caste and religious difference in Jahazpur should contrast strongly with my own. Sometimes we argue openly about these matters, and sometimes we brood silently but palpably. Friction is the word that comes to mind, and in highlighting tensions resulting from our disparate viewpoints, I argue that such friction is fruitful—that dissonant, alternative perspectives may yield enhanced understandings.

One source of friction between me and Bhoju derived from my enthusiasm for documenting Jahazpur’s pluralistic culture. The qasba’s significant Muslim population was to me one of the most important pieces of my study, and I found Jahazpur Muslims, most of them, welcoming with an almost overwhelming hospitality. If Bhoju had his ingrained doubts about Muslims as a collectivity, fortunately all his negative thoughts were impersonal. When it came to interacting with individuals or families he was able not only to present a smiling face but, it seemed to me, to relish discovering a varied religio-cultural universe so close to home.

Bhoju closed a written account of our ethnographic collaboration in Jahazpur with the following words, chastening to me. (Small capitals denote a change of script: words that stand out on the original page from Bhoju’s Hindi composition because they are written in the English alphabet.) “In conclusion: In this kind of work, the ASSISTANT has a more important role than the RESEARCHER, because if the RESEARCHER makes a mistake or asks a question that really shouldn’t be asked, no one MINDS all that much because after all she is a foreigner, and there are a lot of things she doesn’t know. But as for the ASSISTANT, he must think a whole lot and every single question that he asks should take into account the local atmosphere” (Gold, Gujar, Gujar, and Gujar 2014:350). It seems important to recognize the validity of Bhoju’s conclusion.

Figure 9. Window Gate, showing latrines and Shiva Shrine, 2015.