Читать книгу Shiptown - Ann Grodzins Gold - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

This book is about a small town in Rajasthan called Jahazpur (literally, “shiptown”) and the people I met there in the second decade of the twenty-first century. What kind of a place is Jahazpur? First, it is a qasba, a market town that not so long ago was walled and gated. As a qasba Jahazpur united mercantile and bureaucratic functions—a common pattern in this region of North India.1 Jahazpur is a bounded place, an expanding place, an environmentally endangered place, a communally “sensitive” place, a peaceful and beautiful place with a motley but attractive built landscape rendering fragments of its complex history visible. To me it is, most importantly, a peopled place.

I sustained two simultaneous aims while composing Shiptown. My primary aim is to offer descriptions of, and insights into, small-town life in provincial North India. I especially seek to convey the ways a town is both distinct from its rural surroundings and a dynamic hub where businessmen and farmers are in near constant interaction, where two-way passages between two symbiotic but quite different modes of life are normal and persistent processes. Shiptown does not claim to offer a comprehensive portrait of qasba life, but it does attempt to portray some pervasive textures of society, materiality, and popular imagination in such a place at a particular time.

This work’s secondary aim is to contribute to an ever-growing body of literature on ethnographic practice. While not a fieldwork memoir, the text provides more self-disclosure than is usually the case: struggles, trials, errors, inner turmoil, and dependence on the kindness of others. While I do not propose methodological models, I do try to display the ways in which my Jahazpur research was fruitfully collaborative.

Just as Jahazpur qasba is multifaceted, Shiptown the book is a hybrid product. Composed of diverse viewpoints, snapshots, routes, events, and explorations, this text offers a patchwork of descriptive prose, images, journal entries, narratives, conversations, and even a poem (I began several during fieldwork but finished exactly one). Different chapters reflect different approaches to understanding and different interpretive modes and moods; they are voiced in subtly varying tones and composed in varying styles.

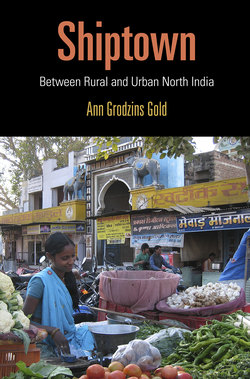

Figure 1. View of Jahazpur from hilltop, showing mosque with tall minaret and many small temple domes.

This introductory chapter sets the scene for what follows, drawing on my earliest interviews (August–September 2010) to sketch the nature of Jahazpur qasba as articulated by its residents. Readers should be able to gather gradually, as I did, some of the ways people in Jahazpur talk about where they live. How shall we think about a qasba? Is it no more than a glorified village or merely a plotted point on the less citified end of an urban continuum? I argue that it is more helpful to see the qasba as a particular kind of North Indian place with characteristics all its own. If the view from the big city deems Jahazpur only dubiously urban, the view from the village understands it as a place with urban amenities (suvidha) both domestic and public. Rural people know Jahazpur as a place where you can “get your work done”—whether it has to do with shopping or with relatively minor bureaucratic negotiations. With numerous government offices and a hospital, Jahazpur is a hub for services unavailable in villages. You cannot obtain a driver’s license in Jahazpur, but you can get a ration card, open a bank account, file a police case, register a land transfer, and conduct similar business.

Qasba comes into English (as casbah) from Arabic via French colonial usage in Algeria. It arrived in Indian languages from the same origin but along a different route. The Arabic term is often translated “citadel,” while the South Asian gloss becomes simply “town.” In Hindi usage I found qasba roughly defined—both by dictionaries and by people I interviewed—as a settlement “larger than a village but smaller than a city.” With its population around 19,000 in 2001 and 20,586 in the 2011 census, Jahazpur fit that bill.2 The semantics of qasba in North India evidently engages more than demography. Not every small town of comparable size is appropriately referred to as a qasba—a designation comprising some ineffable and some very concrete qualities. These have to do with a richly plural cultural heritage, administrative functions, trade, and indeed walls.3 To my mind qasba is a genuine and distinctive third category—neither mini-city nor overgrown village.

Writing of the “globalized city” worldwide, Bayart observes that it “is not anathema to the countryside. The city remains attached to the countryside through rural migration, supply lines, leisure activities, family visits, election campaigns and the political mobilisation of notables” (2007:24). In a sweeping study of Indian cities, through the ages and across geographies, Heitzman states: “A large percentage of the small and middle cities in South Asia existed primarily as marketing nodes and, to a lesser extent, as administrative hubs for rural hinterlands” (2008:208).4 Both observations are precisely true of Jahazpur qasba, and the village/town interface is absolutely crucial to Jahazpur’s market economy. There are constant and multiple exchanges—physical, psychological, political, economic, and social—between town and country. Many qasba families still own village land even if they have lived for generations inside the walls. Marriage ties send city girls to villages and vice versa, sometimes with unhappy homesickness resulting. Every interviewee testified that people from surrounding villages constitute the majority of customers in the market which lies at the heart of the qasba’s very existence.

Jahazpur’s bus stand and streets are crammed with shopping opportunities. I was fascinated by what Jahazpur market sold and equally by what was not available. For example, toilet-bowl cleaner (much advertised on TV and copiously applied to porcelain “squat-latrines”) was on display in every little shop; toilet paper was nowhere. A single brand of preservative-infused white sliced bread could be purchased at a few places in the central market; but in most grocery stores bread came only as hard, cold pieces of toast, sold by the slice and considered good for upset stomachs. As for jam—a legacy of colonialism that has become a drearily gelatinous red staple throughout urban India—it was nowhere to be found. Our simple toaster, purchased in Jaipur, was a curiosity even to wealthy neighbors.

Most of the literature on the North Indian qasba is historical.5 One of the few contemporary sociological approaches to an urban center comparable in size, diversity, and several other features to Jahazpur is K. L. Sharma’s extensive work on the qasba of Chanderi in Madhya Pradesh. Sharma vacillates on ways to describe the mentality of Chanderi. In his monograph published in 1999 he asserts that the town exhibits “true urban consciousness” (16–17). In a later article, Sharma states emphatically that Chanderi may be urban, but “village-like ethos and culture” are “hidden within it” (2003:412). Far from accusing Sharma of contradicting himself, I point out these alternative assessments as illuminating affirmations of the impossibility of characterizing a qasba as either rural or urban. It is definitively both and equally neither—a characterization around which pretty much all interviewees concurred.

Perhaps symbolic of Jahazpur’s dual nature: goods arrive on huge transport trucks from manufacturing centers all over the country and world, but must be delivered to shops in the old city by handcarts. Motorcycles clog the qasba lanes; cars improbably manage to negotiate passage when the need is imperative; large transport trucks are altogether out of the question. Jahazpur is undeniably and self-consciously a “provincial” place: mofussil, or—as people there frequently told me, using English words, a “backward area.”6 Before passing through the gates, as we shall do in Chapter 2, let us listen to Jahazpur describe itself.

Kalu Singh, a Mina man in his eighties, grew up in Jahazpur but has seen a great deal of the world. He served in the army and was stationed first in South India and then in Kashmir. After the army, Kalu Singh worked for years in both Mumbai and Ahmedabad, returning in his old age to settle in his hometown with his wife—with whom, he confided, he had a “love marriage.” (Still unusual today in Jahazpur, love marriage was practically unheard of for his generation.)

Eager to elicit his comparison between the cosmopolitan places he had sampled in his long life and Jahazpur, I posed this question: “Mumbai is the biggest and most modern [sab se bara, sab se adhunik] city in India, so what is Jahazpur?” Kalu, echoing my simplistic locution with gentle mockery, replied: “It is the most *backward! [sab se backward].”

During my first months of fieldwork I often began with simple questions either about Jahazpur as a place, or about the meaning of qasba. Something which puzzled me during this initial period was the way so many town residents were quick to express a negative assessment of their home, just as Kalu did. Based on my experience, albeit limited, of visiting or passing through other small towns in the region, Jahazpur struck me as endowed with many quality-of-life pluses. Its geophysical landscape and its architecture both possessed attractive features. I found the social ambiance equally pleasant—a comfortable union of urban “mind your own business” with provincial courteousness.

Yet it soon became clear that the town had a collectively professed inferiority complex. Many residents told me they were hoping to leave or planning to send their children elsewhere to study and maybe to work. Rarely if ever did anyone mention the lovely view from the fort, the vital charms of the markets, the religious diversity and abundance of temples, shrines, and saints’ tombs. In short, all that made Jahazpur picturesque to my foreigner’s eyes was unexceptional to them. Their big complaint: the town had made “no *progress.”7

Equally perplexing to me were the frequent invidious comparisons I heard made with nearby Devli. Jahazpur, people said, was stagnant while Devli was advancing. In my view, Devli lacked everything that I liked about Jahazpur: gorgeous vistas, deep history, dramatic geography. Devli was a product of colonialism, grown up around a British army camp. It is still the site of a military base, to which many attribute its superior progress, both economic and social. I never properly explored Devli, though I put in plenty of restless time at the bus stand there. Initially a few strolls around the Devli bus stand did not yield an elevated view of greater amenities. However, when I had to wait there at night, I began to see distinguishing features. For example, around 8 P.M. at one of the tea stalls I observed a huge vat of milk at the boil; what would they be doing with so much milk at that time of night, I wondered out loud. To my surprise, I learned that the tea shop stays open all night. Come to think of it, why was I so often pacing at the Devli bus stand? Because, of course, Devli is a transportation hub and buses come and go from larger cities (Jaipur, Kota, Udaipur, Delhi, Gwalior) twenty-four hours a day. Jahazpur’s bus stand, by stark contrast, would be dark and shut down well before midnight.

Chetan Prakash Mochi’s family fled Pakistan in 1947, landing in Jahazpur not many years thereafter. They now have a pleasant home and lovingly tended garden in Santosh Nagar colony—the recently settled suburb of Jahazpur where I too lived. “Mochi” means “shoemaker,” but Chetan and his wife Vimla, probably now in their fifties, have successfully changed professions. Both are tailors, sewing for gents and ladies, respectively. On my first of many visits to their home (for Vimla sewed all my salvar suits that were not ready-made), I was served assorted delicious delicacies and given a tour of the house. I noted in one back bedroom a framed portrait of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, the revered twentieth-century leader of oppressed communities in their struggles for rights and dignity. Mochis, I realized with a start, of course would be SC or “Scheduled Caste”—formerly untouchable as are all groups dealing with leather. But it wasn’t until I saw the picture of Ambedkar that it dawned on me that this family, hard-working but living a comfortable suburban life, might embrace the shared identity of downtrodden communities or Dalits. No Regars or Cha-mars (Rajasthan’s two most populous leather worker castes) lived in Santosh Nagar, to my knowledge—certainly not at this end of the colony where Brahmins and Jats predominated with a sprinkling of Gujars, Vaishnavs, Rajputs, Baniyas.8

Ann: Tell me about Jahazpur. What is it? It seems it is neither a village nor a city.

Chetan: It is a qasba!

Ann: So, if you had to compare a qasba with a village or a city what would you say?

Chetan: In the city there is education, there are hospitals, and in the village you don’t have these things, and if you get sick you have to go to the city. Well, in Jahazpur there is a hospital, but it doesn’t have facilities (suvidha). It isn’t even a good place to go for *delivery [of babies]—not even *normal delivery.

Ann: Where do you go that is near?

Chetan: Devli!

Suvidha might be the word that recurred most often when I asked for a simple town versus village contrast. Suvidha encompasses all kinds of comforts, amenities, conveniences. These include indoor latrine facilities, a reliable, plentiful nal (running water connection), electric power at least somewhat more regular than in rural areas and all that it brings, from basic lighting to fridges, ceiling fans, and the ability to watch your favorite TV serial uninterrupted. Often people used suvidha to cover diverse positive attributes of town versus village. Here, however, Chetan uses it against Jahazpur. Suvidha may stretch beyond domestic comfort to encompass transportation facilities, high-class shopping options, access to competent medical care, and educational choices beyond the basic government school. It is on that second level that Devli particularly outstripped Jahazpur in people’s estimations.9

Madan Lohar moved from his village birthplace to Jahazpur in pursuit of a good living and a good market for his fine craftsmanship in metal. His well-made and attractive metal storage cupboards were objects of desire. He had been operating a highly successful business manufacturing and selling metal furnishings for about two decades in Jahazpur, and his large family lived in a spacious home they had built adjacent to his shop on the Santosh Nagar road. But Madan told us he had already laid plans to move to Devli.

Bhoju Ram, my research collaborator, asked Madan what change he had seen in Jahazpur in the twenty-some years he had lived here, and he answered, “There is no special change! Jahazpur is a village-like town (gaom jaisa qasba), but Devli!—their way of life (rehen sahan), their clothes, in all things they have made progress, in Devli!” A successful Brahmin shopkeeper we called “Lovely,” whose English nickname derived from the name of his store, also posed an extreme contrast between Jahazpur and Devli with an emphasis on Devli’s rapid development. He told us, “When I studied in Devli, there was zero there, but now Devli is ten times better than Jahazpur!”

Many theories were advanced on the reasons for Devli’s rapid progress, which is rooted both in historical and economic circumstances. One is the proximity of military camps and industrial enterprises.

In my conversation with the tailor Chetan Prakash, I said, “I’ve heard that Devli is smaller than Jahazpur, so why is there greater development in Devli?” He explained:

When India wasn’t free, there was an English army camp in Devli, and conveniences (suvidha) were created for the camp at that time; even now there is still a military base and training center there, so that development has continued into the present.

And today there are also other nearby enterprises like the Bisalpur Dam … factories, mines, and highways. Jahazpur, on the other hand, is completely isolated, and that is why it isn’t developed.

At this juncture our conversation took a turn to reveal some advantages to Jahazpur after all. I admit to provoking this shift with a leading question:

Ann: But I’ve heard that Jahazpur is a more peaceful place.

Chetan: Yes there is peace here, but nothing more! Here there is no looting, no theft. In Devli, if you don’t put a lock on your house when you go out, even in the day or just for a few hours, you could get robbed.

Suddenly Devli looks less appealing, and we glimpse at least a tinge of civic pride beneath the rhetoric of self-disparagement.

Neelam Pandita, a young Brahmin woman studying for her nursing degree, had recently moved to the “suburb” of Santosh Nagar with her parents and brother, leaving behind a crowded and unharmonious joint family household “inside the walls.” By nature cheerful, positive, and friendly, Neelam had mostly good things to say about Jahazpur. However, she did critique the availability of educational supplies, telling us emphatically, “You can’t get books in Jahazpur—not any of the books you need to study for the competitive exams, and you absolutely can’t get any books on nursing; I order them from Bhilwara or Ajmer.” Neelam considered space the key causal factor in Jahazpur’s lack of progress, perhaps because a crowded house presented difficulties for her own family that were still fresh in her memory.

When I asked Neelam to speculate on the reasons for the sluggish development of Jahazpur, she explained, “Jahazpur is a small, congested area, and the population has increased. But they are all gathered into a small place. So that is why there is less development here…. Devli is spread out, and there are big suburbs where you can build big houses.”

Another young woman we interviewed, called Tinku, came from a predominantly agricultural community. She stood out among my early interviewees as assessing Jahazpur in a more positive way. I describe her in my mid-August journal as “very voluble,” noting, “Tinku had a lot to say about Jahazpur, she had a lot to say about everything.”10 In our recorded interview with Tinku she readily made comparisons between village and town:

In the village the atmosphere (vatavaran) is good but the education isn’t good. Here there are good schools nearby; business is good also in Jahazpur. Jobs are here. You can’t do business in the village!

The qasba is better than the village; you don’t have to go too far for your work. [She unites here two senses of kam, or work, which can mean in this phrase both “to get things done” and “to get the things you need”]. You can do it all right here. But if you live in a village, you have to go outside the village to take care of your work [whether shopping or bureaucratic]. For that reason Jahazpur is better than a village.

This voice from a young woman with village experience presents what can be appreciated about Jahazpur if you have tried living in both kinds of places (and if you cease indulging in a grass-is-greener yearning for the dubious charms of Devli). The very things Tinku highlighted I also appreciated, for I too had shifted from village to town.11

Each of the five chapters in Part I—Origins, Gateways, Dwellings, Routes, and Histories—recounts in detail how people and communities use and transform places through imagining, residing in, and traversing them.

The first chapter relates the mythic origins of Jahazpur, well known to all its residents, and offers ethnographic elaborations embroidering these legends’ meanings. Chapter 2 enters Shiptown, the place and the book, through multiple openings. The town is walled and gated, thus not only contained but permeable. While gazing both ways through its five and a half gates, I highlight thematic motifs that crisscross the whole.

Chapter 3 begins from my own fieldwork circumstances and practices as they emerge from the increasingly undisciplined discipline of anthropology. Fieldwork produces a particular kind of lived relationship to place and to neighbors; cohabiting is a method of sorts. From attending to those neighbors with whom I interacted regularly, it requires no shift in focus to talk about gender roles in a new kind of place: a small town’s still smaller suburb or “colony” (an English word fully incorporated into Hindi). Fieldwork is ever permeable to emotions even while generating data.12

Chapter 4 focuses on how, in a fundamentally plural place, religion periodically overflows its primary interiority (whether temples, mosques, or hearts) to fill up town streets with visual and aural sensations generating sensory surfeit. Equally, this chapter about parades and other festive modes of claiming space may enhance understandings of identity, tension, and peacekeeping. Chapter 5 turns to the depths of the past in order to ponder how these do and do not appear on the surface in present times. It is in part about the layers of displacement that centuries precipitate, and how some groups organize themselves regularly to remember the places they once lived and ritually revisit them. It is also, in part, about how some people accidentally rediscover the past underground and respond to it. Here I seek to evoke the ways places speak of history and history speaks through places—processes that are meaningful to communities.

Part I thus begins with names and tales, then meanders in and out the qasba gates and up and down the road leading from the bus stand to the colony Santosh Nagar. It parades noisily all around the qasba streets and makes several quick excursions to the surrounding hamlets, attuned to oral histories tapping the depths of the past. Of course there remains a great deal left to learn about Jahazpur and its residents.

Each of the three chapters composing Part II of Shiptown grapples with a particular set of complicated, purposeful human activities which develop around areas glossed, for drama and convenience, as Ecology, Love, and Money. My selection of these three foci for human endeavors is based (as I believe most honest ethnographic explorations are) on a partially serendipitous, partially plotted blend of what fascinated me, what presented itself readily to me, and what I realized I had better not ignore if I wanted to stay true to my larger project. That ultimately was to write a good book about a qasba and its relationship to the rural that surrounds it.13 Each of these clusters of activity—ecological, social, and commercial—offers a panoramic window onto rural and urban interchanges, fusions, transformations, oscillations.

Environmental protection, marriage, and trade as human projects exist throughout the globe, inflected by locality. Sometimes alone, more often in association with Bhoju and his daughters, I observed, experienced, and queried these projects in Jahazpur. Whether focused on unique instantiations or seeking connective threads among multiple cases, my attempt remains above all to be attentive to myriad locally embedded specificities. Part II thus fleshes out ethnographic explorations of Jahazpur as place in three different ways. These are how to protect and sustain valued environments; how ritually and materially to ensure the future happiness of couples and satisfy the pressures of society; and how to keep one’s business afloat in the unstable world of the market ridden with uncertainties but also with promises. Part II’s chapters represent learning experiences for me as an ethnographer—sometimes tentatively, delicately, blindly groping my way; sometimes racing into the purely unknown, as if on a dare; sometimes beckoned by others, sometimes barging in quite uninvited. Each project I consider also constitutes for participants a kind of activity involving the acquisition of knowledge, the development of strategies, the transformation of selves.

I drew the content of Part I from my whole year’s study and organized the bits and pieces in order to layer content and build up understanding. By contrast, a fieldwork chronology loosely structures Part II. That is, I follow my own learning experiences: the trees predated and overlook this fieldwork, while the river occupied Bhoju and me between Diwali (mid-November) and winter. The wedding was a bright gash in the midst of my research and dominated the brief cold season. The market, my last big focus, we pursued in the relentlessly increasing heat from March into June. There’s a neat circularity too, as the very latest effort to save the river, observed on social media and my most recent return visit in 2015, is above all a shopkeepers’ movement, aligned with ideals of self-improvement within qasba culture. Underlying these ideals is the conviction that an improved environment would also improve business.

Chapter 6 also follows closely from the last chapter of Part I, because one of the wooded hilltops, the first one to which Bhoju called my attention, is protected by the Mautis Minas. Engaging with trees and river has in some ways framed my entire encounter with Jahazpur. The trees brought me there to begin with, drawing me from rural to urban, from village to town, via Malaji’s sacred grove. The river and its travails flowed or trickled into my consciousness only when I heard in the fall of 2010 about a hunger striker’s efforts to save it. Thus Chapter 6 bridges two contexts and eras of my Rajasthan anthropology, juxtaposing successful tree protection and an ongoing struggle for river restoration, asking why the former has been more easily executed than the latter.

In Chapter 7 I practice full participant observation during about a month of preparation for, as well as aftermath of, the wedding of my research collaborator Bhoju Ram Gujar’s three daughters, two of whom are coproducers of this book. You could say I suspended my fieldwork, or you could say I was more intensely engaged than during any other time period. When the date was first set, the family was undecided as to whether the wedding would be held in the brides’ home village of Ghatiyali (my former fieldwork site and Bhoju’s birthplace), or in Jahazpur, where most of the family currently resided. I remained a neutral listener while different persons advocated for different venues. Grandma really wanted the village; the girls were rooting for Jahazpur with their collective if modestly muted might. They knew that in the end the choice of location, just like the choice of bridegrooms, would be Papa’s, not theirs, and Papa would do what was best. When it finally was settled that it would be a town wedding, town elements, costly ones too, were incorporated into it. I intuited, but never heard expressed in words, that the decision was based in part on the young women’s wishes, in part on the prudence of avoiding certain difficult relatives in Ghatiyali, and in part on the ways that town life had genuinely transformed this family’s aspirations.

The market, of course, is the paradigmatic meeting place of town and country. Vegetables come in from villages, as do shoppers whose needs, from blue jeans to tractors, are served by town tradespeople. In Chapter 8, the last substantial chapter of Shiptown, I finally arrive at its (mercenary) heart. Arguably, I might have come to the market immediately following Chapter 2: every gate, after all, leads to or from its central space. As periphery, Santosh Nagar depends on the center; if there were no qasba, there would be no colony. However, my choice to retreat in Chapter 3 to Santosh Nagar (thus to gender, to domesticity) was reasoned and deliberate. Shopping lists begin at home.

When in Chapter 4 we look at the carefully negotiated routes of religious processions and the defining, peace-producing fear of danga (riots) as bad for dhandha (business), we of course traverse the market streets and listen attentively to shopkeepers’ concerns. Pluralism is as much or more a by-product of commercial life as it is of peace committees. We begin to apprehend that the priorities of having a peaceful environment for buying and selling was a large component of the “good-feeling” (sadbhavana) process. Moreover, shopping stimulates integration across religious communities: even modest young Hindu women will venture into a Muslim shop (for example, Gaji Pir Gota Center) in search of sparkling trim, if the variety and quality of selection is, after all, the best in town.

The intricately intertwined histories of nonviolent Jain merchants and Minas as farmers/soldiers—presented in Chapter 5 as crucial to contemporary Jahazpur society and politics—also importantly underlies market transactions. In the market, most shopkeepers spoke fondly if somewhat patronizingly of Mina customers, who account for a huge percentage of their trade and were regularly characterized as ever eager to buy the latest fashion. Finery-loving Minas pit their wits against merchants determined to empty their pockets. How might this resonate with goat-sacrificing Minas possessing access to the dangerous power and potent blessings of the non-vegetarian goddess who requires respect from vegetarian Jains? These stereotypical roles seem set in an eternal dance in which each plays their part with vehemence and an underlying awareness, I am pretty sure, of the scripted nature of their interactions.

The refreshingly secular self-help “Save the Nagdi” cleanup team, invoked at the close of Chapter 6, emerged a few years after my fieldwork concluded and includes Hindu, Jain, and Muslim shopkeepers. The salient term here is shopkeepers; religious identities seem to lack relevance. I by no means intend to imply that religious identities are not important in the qasba; the accelerated proliferation of processions and construction projects among all Jahazpur’s religious groups depends heavily on donations from businesspeople—donations that depend in turn on profit, that is, on surplus. However, alliances can and do form across religious difference on the basis of improving the atmosphere and reputation of the market; an improved market enhances resources available to fund separate religious projects.

As Chapter 7 will highlight, to point to the commercialization of items used in wedding rituals may epitomize apparently trivial but cumulatively consequential aspects of urbanization, especially for those traveling on the slow passage by “ship” from rural to urban. These ritual props are not terribly costly, but with apparently increasing sales volume they seem to add up to worthwhile business opportunities. I don’t know what percentage of business in Jahazpur is generated by weddings or more broadly by life cycle ritual celebrations. Festivals such as Diwali and Id were mentioned by every purveyor of cloth and clothing as highlights of the business year. Still, it would not surprise me if the commerce stimulated by weddings were calculated to be equivalent to the staggering proportion of sales dependent on Christmas in the USA. Just that protracted cloth-giving ritual, the mayro, means many thousands of rupees to dealers in cloth, as merchants emphasized in our interviews. The sellers of silver and gold ornaments could hardly stay afloat without the trade generated by gifts at weddings and requisite dowry items. In addition, think of the sweet makers, the tent house at the bus stand that rents out all kinds of hospitality necessities, the light decoration people, even the tailors. Weddings in general are vital to a healthy market in many different areas.

If the trees brought me bodily to Jahazpur, at the time I saw the town only as a blob adjacent to the hilltop. What eventually drew my mind into investigating Jahazpur as place were the legends naming it a pitiless land. As they initially provoked the research on which this book is based, I begin with these tales.