Читать книгу Shiptown - Ann Grodzins Gold - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

Colony

Suburban Satisfaction

We also produce knowledge in a mode of intimacy with our subjects. Hence ethnography as a genre seems to me to be a form of knowledge in which I come to acknowledge my own experience within a scene of alterity.… In being attentive to the life of others we also give meaning to our lives or so I feel…. So ethnography becomes for me a mode in which I can be attentive to how the work of very ordinary people constantly reshapes the world we live in. (Das 2015b:404)

Fieldwork is life itself. (ca. October 2010, author’s optimistic email to colleague)

Suman [my neighbor, chiding me for speaking as if we lived in the qasba] “This isn’t Jahazpur, this is two km distance from Jahazpur, this is Santosh Nagar!” The truth! (30 April 2011, author’s journal entry)

Having introduced Jahazpur qasba and looked both ways through its gates, grand and small, I now turn my back on those historic portals for a chapter and portray the place where I lived, ate, slept, and got to know my neighbors. What I did for large parts of my days when I wasn’t occupied with research and/or shopping forays into town will also emerge. Whether hanging out my hand-washed laundry on the roof, chatting with women or kids on the roof or in the street, taking tea with a shopkeeper when their business was slack, or watching TV with Bhoju’s serial-addicted daughters, I felt no qualms in asserting I was conducting valid fieldwork. But there’s always a catch, and here is where ethnographic self-doubt lurks and clutches me: I lived outside the walls. In a way, my Santosh Nagar life felt organic and real, while my more formal “research” life—recording interviews, documenting hectic religious processions, photographing sites of historical importance, observing practices of commerce, and so forth—always made me feel a bit like a poseur.

This chapter has several related aims, but all are thoroughly embedded in the residential colony of Santosh Nagar, and all are inflected by gender—my own, my helpers’, my neighbors’, my friends’—all of us female (discounting Bhoju Ram, who was rarely present when I was hanging out in Santosh Nagar). Women’s roles, preoccupations, and limitations are not the entire content but certainly compose the ballast of this chapter. My portrait of Santosh Nagar cannot claim to be wholly balanced. Much of what I say about the place comes through the mouths and experiences of women.

If this seems an unjustifiable skewing in a book that is after all about Shiptown and not about women, I have two rationales. The first of these is simply experience. The Santosh Nagar life I shared was largely life as experienced by women. This extended to my similar dependence on men for any transportation other than my own two feet. The second rationale for this chapter’s focus must give away in advance one of its main conclusions. This is that men who live in Santosh Nagar believe they live in Jahazpur, while many Santosh Nagar women feel that they do not live in Jahazpur. It was April, well over halfway through my stay, before I finally admitted to myself that Suman (as cited in one of this chapter’s epigraphs) was as usual correct in her insistence that I recognize that neither she nor I actually was a Jahazpur resident.

It took me that long to hear what these women were telling me: that it was foolish to ask them how they liked living in Jahazpur when they did not actually live there. Why was I so dense? I suppose because I knew I was doing an ethnographic study of the town of Jahazpur. My neighbors’ distinction between qasba and colony was peculiar to their gender, with its limited mobility. The men of Santosh Nagar were far more integrated into town life for a very evident reason: they could jump on their motorbikes (as Bhoju did multiple times every day) and be at the bus stand or inside the qasba walls in just a couple of minutes, negligible time, no distance at all. Women in these parts still didn’t drive or bike.1 To get to the qasba women and girls must either walk or be passengers, dependent on male drivers: husbands, brothers, and fathers. If there were no husband, brother, or other trusted grown male around to ferry them, they might easily walk to town in nice weather, and get there in about ten to twelve minutes. But rain (which produced mud), cold, and heat all rendered this walk less appealing at various times of the year. For those who had small children in tow, of course, the distance was magnified at any season by the weight or whines of an infant or toddler.

It is not a long or difficult walk between Santosh Nagar and the bus stand, but women have their modesty, their vulnerability to think about every time they go out. Girls prefer to go in pairs or larger groups if they do walk. And there are spaces they rarely enter. I was really shocked when early in my stay, I had to mail something, and I still didn’t know my way around town very well. Bhoju’s middle daughter, Chinu, an educated college girl, accompanied me to the post office. I sensed an aura of nervousness in her normally poised and confident demeanor; later she told me she had never before been there! In my own subsequent trips I rarely saw other women inside the post office; certainly there were none working there. Old behavioral constraints die hard; every public space offers a challenge, an unwritten rule or a rule no longer posed blatantly but built into habitus. Going to the post office would hardly brand a woman as brazen or out of control; still you rarely see women in the Jahazpur post office. This is quite unlike Jaipur, Rajasthan’s capital, where not only many of the patrons but many of the postal workers are themselves female. Thus it bears noting as weighing on the village side of qasba life.2

This chapter has three sections with particular aims. In the first part I aim to characterize Santosh Nagar as colony—a different kind of place in contradistinction to the qasba, although intrinsically connected with it. Second, I aim to bring to life fieldwork days spent in the context of Santosh Nagar, and especially to describe the ways that Madhu and Chinu Gujar, Bhoju’s two elder daughters, helped me learn. Madhu and Chinu “officially” worked for me on and off during my fieldwork, assisting me in getting to know the neighborhood women, including scheduling and conducting interviews. Together we probed the dynamic intersection of gender and place in a relatively newly settled neighborhood. How do women in such a new kind of place reinvent some traditions, choosing styles in which to enact stability, or even to break free (if covertly) in some limited fashions? That is, how are changing gender roles in changing times produced in a very particular kind of setting? Here, acknowledging inspiration from Doreen Massey, and using language borrowed from her, I describe a ritual and translate a ritual narrative to get at some crucial fragments of the whole.3

The final segment of Chapter 3 explores the rather different ways a different young woman taught me about life in Santosh Nagar. This was Suman, whose voice and views are present in Shiptown. Her judgments of me and of her surroundings had a strong impact, if a gradual one, on my subtler understandings. Suman lived between my home and Bhoju’s and often detained me as I passed. She asked me many questions, while actively resisting being a subject of my research. In spite of her deliberate recalcitrance vis-à-vis my formal fieldwork, Suman became a force in my mind; her voice often echoed in my head, and was transcribed in my field notes.

What Kind of Place Is Santosh Nagar?

Santosh Nagar seems like a place of many random paths crossing; what makes a neighborhood? what gives a feeling of neighborliness? (11 August 2010, journal)

If you don’t count Chavundia (once numbered among the twelve hamlets but now more like a mohalla or qasba neighborhood, in spite of being outside the walls), Santosh Nagar is Jahazpur’s oldest and most populous “colony.”4 Colony is a loanword from English, used to refer to a planned suburb or housing development. Santosh Nagar was both and neither.5 It was neither distant enough, nor bounded enough, from the center of town to feel like a true suburb; and it wasn’t planned enough to feel like a “development.” Some referred to Santosh Nagar as basti (a broad term applicable to any human settlement), but it was never called a neighborhood (mohalla). Those were inside the qasba.6 In Jahazpur municipality’s electoral rolls, Santosh Nagar counted as Ward #3 (among twenty wards all told). Our elected ward member was a politically savvy Khatik, Babu Lal, who won easily in the 2010 election limited to Scheduled Caste candidates. At the far end of Santosh Nagar where I lived there were just two SC households: one mochi (shoemaker; originally refugees from Pakistan) and one dholi (drummer, from inside the walls).

The rather bland appellation Santosh Nagar (Satisfaction City) was bestowed at some relatively recent point in time. Santosh Nagar is a straight shot from the center of Jahazpur. Its fuzzy boundary begins just past a large complex of government offices (all those that had previously been located at Nau Chauk), somewhere around the Muslim cemetery. This proximity to a graveyard is why the locality was initially known as Bhutkhera (Ghostville), a designation still used by many old-timers who live in the qasba. Bhutkhera was the area’s name when no one resided there (except for the dead). Santosh Nagar as a populated colony came into existence gradually over the past thirty years through a combination of officially authorized land auctions leading to deeded ownership, and squatters’ encroachments that, once a house has been constructed, appear thus far to be seldom if ever challenged.

The colony has mostly grown up along both sides of the main road. Between the graveyard and the last homes of Santosh Nagar were lateral expansions on multiple cross streets which rarely stretched more than a block or two on either side. At the tail end where we lived were a few homes which, their owners seemed eager to tell me, had been built well before the neighborhood itself existed, as well as many that are newer, gradually filling in what had been empty space or empty plots.

Mohan, a Rajput matron whose marital family had moved to Santosh Nagar at an early stage in the neighborhood’s development, told us that when they purchased their home, about twenty-five years ago, “there was nothing between Santosh Nagar and Jahazpur; the thana [police station] and tehsil [subdistrict headquarters offices] weren’t there; the first thing was the Jats’ house, and the rest was *plots.” Daji (the Jat patriarch) confirmed that he had purchased his plots and begun to build on them in the 1980s.

Saraswati Sindhi, who lived right across the street from Bhoju Ram’s family, told us in an early interview that at the time of her wedding, when she first moved to her in-laws’ house in Santosh Nagar, “there were snakes and scorpions, and rats.” She elaborated: “From the post office, on this side, it seemed exactly as if it were a jungle, there was nothing, there was no electricity. Now there are streetlights, there weren’t any of those either.” Affirming her observations, I asked unnecessarily, “So there has been a lot of change?” She answered emphatically, “Yes, it was complete jungle! But now it has become a basti (settlement).”

Seeing a good opening in this description to get at local history, I said, “I heard this place was called Bhutkhera.” Saraswati, who made no pretense of appreciating her place of residence, answered, “For me, even today it is still Bhutkhera. When they started selling plots here, they named it “Santosh Nagar,” so it would strike people as good.” (She digressed then from local history to speak scornfully of how only weak-minded people, unlike herself, were afraid of ghosts.)

Kalu Singh, the retired Mina who had returned to Jahazpur after an adventurous working life and whose views I cited in the introduction, described Santosh Nagar before he built his house. He said that thirty-five years ago, “you couldn’t even get here, there was no road, nothing! There was only jungle, and thorn bushes; Bhils would gather wood and sell it for fuel. When there was still royalty in Jahazpur, horses and camels belonging to the rulers grazed in the jungle right here where Santosh Nagar is today.” The Bhil are an ST group that historically lived off of forest products.7

As it approaches the end of the colony where Bhoju’s family lived and where my husband and I resided, Santosh Nagar Road becomes known as Ghanta Rani Road, for once past town it leads a few kilometers farther to the regionally famous goddess shrine of Ghanta Rani (Valley Queen)—a place I had first visited in 1981 when studying regional pilgrimage. Ghanta Rani was near enough that her Jahazpur devotees told me they sometimes made round-trip foot pilgrimages, barefoot, in a single day. On monthly dates special to the goddess, jeeps and trolleys overflowing with pilgrims passed by on their way to Ghanta Rani. Her annual fair drew huge throngs of devotees.8

Just beyond Santosh Nagar, a few minutes’ walk further in the direction of Ghanta Rani, another housing development, already named Shiv Colony, is coming into being. Plots had been surveyed and sold, and by the time Daniel and I left in June 2011, a few houses were going up. But many of the plots had been purchased as real estate investments and remained empty as late as 2015, perhaps indicating that Jahazpur was not growing as fast as some expected. Another reason given to me for the slow pace of Shiv Colony becoming populated is that investors, or speculators, were biding their time, convinced that the price of land would only go higher. Still, some families have begun to settle there, and power and water hook-ups are available for the new plots.

During our fieldwork year, Dan and I liked to stroll through and beyond Shiv Colony in the cool of the evening. Once past the empty plots or scattered construction sites, where sometimes a worker greeted us, we encountered only goatherds and shepherds who daily take small flocks out to forage, ranging across the uncultivated, rocky grazing lands that characterize the landscape on this side of Jahazpur qasba: a source of fodder, firewood from thorny mesquite, and little else.

Bhoju bought his home in Santosh Nagar in 2007. The first time I visited, that same summer, when all the interior paint was new, small representations of Ganesh, the god of beginnings rendered in bright orange paint, were still visible above every doorway in the house. They had been painted for the ceremonial inauguration of the family’s new lives as home-owning townspeople. Three years later, at the beginning of August 2010, my husband and I settled in a rented flat just one street over from where Bhoju’s family lived. We had agreed with Bhoju’s suggestion that we rent in this area and not seek housing in the heart of Jahazpur qasba, a decision finalized in a single day that profoundly impacted my fieldwork and shaped this book, for better or worse. Bhoju had scouted potential rentals in advance of our arrival. He conducted us to three or four possibilities the day after we reached town. All of these were within a few blocks of his own house.

The overriding, important reason for staying where we did was to be close, a neighbor, to Bhoju and his family. I could see their rooftop from my rooftop and this pleased us all. At this time all three of Bhoju’s daughters, not yet married although their engagements were fixed, lived in Jahazpur while pursuing their education. One son was in boarding school (which he disliked) not far down the Devli road. The youngest son lived with Bhoju’s wife and mother in their village home in Ghatiyali. Except during the protracted season of the wedding (Chapter 7) these three significant family members were not often present.

There was one more reasonably weighty justification for positioning myself outside the walls while studying the qasba: physical and psychological comfort. It was much easier to find commodious rooms and relatively more (if far from absolutely) private space by settling in this newer area where plots and homes were simply larger. In terms of ethnographic work, privacy is not always a desideratum; my earlier fieldwork experiences were often richly abetted by exposure, permeability. Having an unintrusive nature, not at all well suited for a career in anthropology, being intruded upon by others is actually good for me. However, my husband, whose company I dearly value, had come with me. He was finishing a book manuscript and needed a quiet place to work, a long day’s journey from his main research site in Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh (D. Gold 2015).

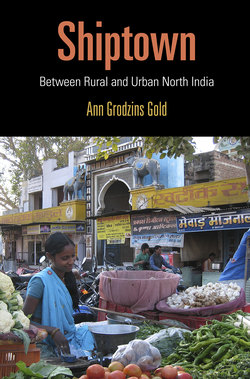

Figure 10. View of rooftops and street where author lived in Santosh Nagar; woman carrying firewood; motorbikes.

Dan and I resided in our Santosh Nagar flat through the middle of June 2011, for the better part of a year. We had two inner rooms with doors—one our bedroom and the other a shared study with two small writing desks obtained locally, and two desk chairs purchased on an emergency run to Jaipur when we realized our aging backs were in deep trouble. We had one Internet card and it only worked on Dan’s machine, and then with a slowmotion quality that felt like the virtual equivalent of walking in rubber boots through a sea of molasses. Our accommodations also included a small kitchen with sink and shelves, in which we installed a typical two-burner stovetop fueled by a gas cylinder (normally rationed but magically obtained for us by friends through channels into which we discreetly refrained from inquiring). We also had a sitting and dining space with two plastic chairs, a plastic coffee table, and a small fridge. Unlike the two side rooms, this central sitting space was semipublic. A large metal grating covered most of the floor, and directly beneath it was our landlord’s front hallway, allowing the passage of air, and of course sound. On both sides of this ceiling/floor courteous discretion on all our parts limited visual intrusions, but we had no way not to hear one another’s arguments and smell one another’s cooking. Our sitting room also offered the only passage to a shared rooftop strung with all-important clotheslines in daily use by all of us. From the roof Daniel and I had access to our own “latrine-bathroom,” two separate spaces next to one another each with its designated bucket, and water on tap from the rooftop tank where it would (under auspicious conditions) be pumped up every other afternoon when the town supplied water to public and private faucets.

The three-generational family with whom we shared our space, and to whom we paid our rent, consisted of five adults and two children, a boy and a girl, whose ages at the time were around six and five respectively. My unfulfilled yearning for grandchildren meant that I never minded hearing them repetitively recite their school lessons in a charming singsong lilt. The adults were a retired teacher and his wife; their son and his wife (whose first child was born after our time living there); and their divorced daughter, mother of the children, who together with her brother and father worked in a small store they owned. Sometimes two additional married daughters, each with two somewhat older offspring, came to visit, and at those times the noise and rowdiness level could get overwhelming. But we grew very fond of the boy and girl who regularly lived below us and who would bring up our milk and our newspaper each morning, melodiously and exuberantly announcing their arrival by calling, “Auntie-ji!, Uncle-ji!”

In contrast to the more homogeneous neighborhoods in the congested heart of Jahazpur’s old walled center, Santosh Nagar is a locality with a radically mixed population. Castes are mixed: persons from the top, middle, and lowest realms of the Hindu ritual hierarchy live in Santosh Nagar, including priests and butchers, shopkeepers and drummers, herders, farmers, and artisans. On one street with which I was familiar, right across the main road from our own street, three houses in close proximity belonged respectively to a Brahmin, a Rajput, and the neighborhood tailors mentioned earlier who belonged to the SC Mochi or shoemaker community. The Khatiks (butchers by hereditary identity) are clustered at the other end of the colony, closer to the bus stand and the qasba, forming Santosh Nagar’s most homogeneous area caste-wise. Judging from the few interiors I saw in that part of Santosh Nagar, these were upwardly mobile, middle-class Khatiks by and large.

Economic classes are mixed: Santosh Nagar residents pursue a variety of livelihoods: some hold salaried government positions; some run small businesses; others might be shopkeepers, truck drivers, or day laborers. At our end of the street a wealthy patriarch, a self-made businessman, owned four huge houses, one for each of his four sons; he was building more for his grandsons. Origins and years of residency are mixed: recent migrants from the surrounding countryside in pursuit of economic and educational opportunities live next door to families deeply rooted in Jahazpur town, who have shifted to Santosh Nagar to escape uncomfortably close quarters, both physical and interpersonal.

Religious identities in Santosh Nagar are distinctly less mixed. Predominantly Hindu, Santosh Nagar’s population did include several Jain families. While the vast majority of Hindus belonged to families rooted in the immediate region, there were also a few whose immediate forebears had migrated from Pakistan around the time of partition. There was one family of Sindhis who held themselves apart from other Hindus in various ways including dress (even adult women wore kamiz-salwar rather than Rajasthani outfits).9 I interviewed several women in the Sindhi family, as well as several Jain women. Interestingly, although Hindu, Sindhi women like their Jain neighbors spoke of themselves as different, and explicitly expressed their sense of lack of community. Nonetheless, the same individuals regularly joined other Santosh Nagar women’s rituals and in that sense were well integrated. No Muslims had moved to Santosh Nagar. Jahazpur’s well-off Muslims possessed considerable property inside the qasba and nearby farmland outside of it. Possibly they had no need for the kind of added space that attracted Brahmin and merchant families, as well as former butchers, to shift from cramped quarters within the walls to more spacious dwellings in this colony outside the qasba. Or there may be deeper limits to residential pluralism than were ever articulated to me.

Many of my neighbors in Santosh Nagar were financially secure but far from affluent. They were at a far remove from that cosmopolitan middle class that ostentatiously consumes global brands. However, many did possess motorcycles, color televisions, and fridges.10 One thing that struck me was how carefully the people I knew cared for their possessions, protecting them from the constant accumulation of dust and cleaning them diligently and frequently. Summer heat was intense, but air-conditioning was not practical in Jahazpur due to power cuts as well as architectural design. Many homes in Santosh Nagar did possess “coolers”—large, noisy machines that created powerful blasts of blissfully chilled air in a very limited space and had to be frequently fed with water (often in short supply). Dan and I purchased a small one on wheels at the peak of the hot season but it was of disappointing efficacy. We had to take turns positioning ourselves directly in its air flow to benefit from it.

While I was living there, the bourgeoisie of Santosh Nagar were just beginning to acquire “inverters”—large cells capable of storing enough power when current flowed to keep some fans and lights running for up to six hours during electricity cuts. Usually cuts were not that prolonged.11 At night, of course, it was easy enough to see who had one of these, and to desire to join that privileged company (although we never did). On my three post-fieldwork visits, I observed that inverters had rapidly proliferated—a substantial investment that doubtless pays off, improving quality of life in multiple ways. Bhoju was motivated to acquire one largely to prevent computer crashes, as well as avoid the hassle of intermittent darkness; his TV was not hooked up to it. I noted in other households that inverters keep the television going for those who do not want their favorite programs interrupted.

If rural and town lives intersect commercially inside the walls, in Santosh Nagar the meeting of town and village was most evident in domestic configurations. I met many village-born persons who lived there. While quite a few of these were women moved by marriage, others were men moved by jobs or business opportunities. All those who had recently shifted to Jahazpur maintained strong connections with rural origins. While it was an exception not the norm, there were a few women (among my acquaintances, notably Saraswati Sindhi from Kota and Asha Jat from Ajmer) who had grown up in more urban areas but whose marital lives deposited them in this backwater. They both articulated interesting and distinctive perspectives on the qasba and its suburban periphery (Gold 2014b).

I learned so much by living a woman’s life in Santosh Nagar, I must acknowledge in advance that when I write about the qasba in later chapters, my insights into the gendered nature of experience are more limited. It isn’t just the disproportion in numbers of interviews, although that is striking: I have about forty interviews recorded with Santosh Nagar women, and not more than a dozen with women inside the walls, where my female helpers had fewer connections and where it was far easier for Bhoju Ram to make appointments with men. The difference in interview numbers hardly reveals the real difference based on everyday encounters and experiences—a difference beyond reckoning.

Gendered Days, Gendered Methods, Gendered Visions

The girls think of their studies, of relationships, of child marriage and love marriage and nata [remarriage]; they all have their eyes on the prize of “sar-vis” [service, that is, a job] without a lot of faith but with a lot of hope and I don’t know, Karuna’s word, aspiration.12 Yes, aspiration. this generation is doing tuition, coaching, big time. almost as their parents are doing vrats. spend money for the future and the future is to succeed in the competitive examinations, to get scores that put you in the running for the next competition. a girl whose marriage has gone bad may be returned to the world of education. a girl who never married must find her match in the world of education. (23 August 2010, journal)

As related in the preceding chapter, Bhoju and I began to work almost immediately after my arrival in order to gather some foundational knowledge about the town that would help me start to focus in, to transform my unwieldy subject of identity and place into manageable chunks. At this early stage, when I knew virtually nothing, anything I learned was useful. When I was not out with Bhoju and not at my desk alone, I was in the company of women.

Given Bhoju’s taxing schedule and my wish to gather women’s viewpoints, it made sense to both of us for me to hire his daughter Madhu (whose schedule at this time had relative flexibility) to work with me when Bhoju was otherwise occupied. Madhu and I did considerable research together from August through October. Chinu began assisting me after that, when Madhu was preparing for a crucial examination and simultaneously ill with a diagnosis of typhoid fever requiring a strict regimen of diet and behavior. From the middle of December to the middle of April neither Madhu nor Chinu was much available due to the compelling preoccupations of both their weddings (in late January) and their schooling (ongoing). As is common, they both did return home after their marriages, and we did work together again, sporadically but very fruitfully, in the hot season.