Читать книгу Mortal Doubt - Anthony W. Fontes - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBring Out the Dead

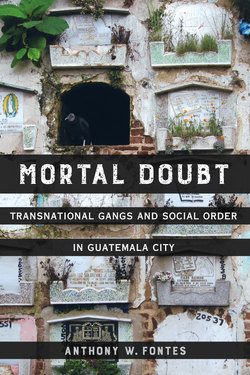

FIGURE 4. Where city and cemetery meet.

This narrative is an experiment in ethnographic storytelling. It splices conversations and information from several interviews with Calavera and sublimates analysis into the narrative arc. Names, dates, and details have been changed to protect the subjects.

Guatemala City, May 2012. Calavera eases open the door and eyes the street he grew up on. Blurred figures slip beyond his peripheral vision down an alley. Children from the neighborhood? Or perhaps not. Tinkling laughter. Nothing to fear. Then again . . . he knows well enough the demons lurking in children’s smiles. They make the best lookouts. Watching, just watching, they go. And didn’t Casper once call you his little chucho. Just let the dog off the chain and see . . .

Across the street the tiendita he knew as a child has been painted blue, “TIGO” stenciled in white block letters. His own Mara Salvatrucha tag is somewhere beneath those layers of paint. Behind the tiendita’s black metal grate, a small girl sits on a stool among Doritos and Lays potato chip bags strung up like baitfish among sacs of fried pigskin, plantain chips, and suaro for babies sick with fever. A refrigerator glows behind her, brown glass bottles sweating within, and beside the refrigerator rusted propane canisters are stacked like ordinance from a forgotten war. The girl watches the street without blinking, her lips pulled back in a half smile, gold teeth glinting in the sunlight slanting over the tin rooftops.

I stand before the arches of the cemetery entrance, waiting for Calavera. I have a small silver voice recorder, a camera, and a journal in a green US Army surplus satchel. Flower vendors clog the sidewalk. The scent of carnations and roses wilting in piles filters through the stench of burning garbage on the breeze. Further down the boulevard, the city morgue is abuzz. Men in white lab coats haul forensic equipment in and out. A line of silent visitors stretches out onto the sidewalk, waiting to identify the recently dead. Funeral home operators—wearing dark glasses and tattered blazers—linger among the aggrieved, handing out business cards. A month from now I will pose as a mourner and come to find the body of a young man named Andy. Government officials will not answer my queries. Eight years ago Calavera stood here holding his sister’s hand as she waited to identify her murdered husband. Then as now, coffin makers and stonemasons bend to their labors across the boulevard, their hammers echoing through the traffic. I mull over my plan: walk with Calavera to his brother’s grave and record his memories of growing up, his brother’s death, and their time running with the Mara Salvatrucha.

Calavera steps out and shuts the door quietly behind him. For a few heartbeats he lingers, tracing in his memory the constellation of bullet holes above the door long plastered over. Then he’s on the street, watching the neighbors’ shuttered windows as he walks. Few of his old compatriots remain who might recognize him. Except for Casper, who hardly ever leaves his safe house in El Trebol. Still, Calavera wouldn’t have even come here if he didn’t long to see his sister and nieces. Quickening his pace, he walks past a handful of boys kicking a rumpled blue plastic ball. They stop their game and watch him disappear down a cement footpath winding beneath electricity wires strung like sad nets to catch the falling sky.

“Hey, Anthony.”

I turn and Calavera is standing before me. We clasp right hands and embrace. He has lost weight since leaving prison, and he was skinny to begin with. His shoulder blades are sharp against my arms.

“What’s the vibe?”

Calavera shrugs. “All good.”

“Well, uh, shall we go?”

“Right on.”

We walk through the cemetery’s vaulted entrance and down a paved boulevard lined with ornate mausoleums and cypress and walnut trees. The street noises quickly fade.

“So . . .,” I begin. Last night I wrote down a list of questions—probing, intelligent questions with a subtle, penetrating arc. But now I feel like a clumsy stranger prying into another’s pain. I hold the recorder awkwardly between us, the red light blinking. “Have you been here since you got out?”

“No.” Calavera shakes his head. He has passed the last six of his twenty-five years languishing behind bars. The previous five he spent snorting, smoking, and selling drugs and shooting at rivals. The gang told him it was the way to avenge his brother’s murder.

We walk past the wealthy dead. A forty-foot-tall knockoff of an Egyptian pyramid looms on the left, replete with a pharaoh’s head and stylized hieroglyphs. It belongs to the Castillo family, who it is said became fantastically rich by monopolizing the national beer industry. Gallo, la cerveza mas gallo! An elderly couple—a woman wrapped in a rainbow shawl, a man in overalls stiff with mud—peer out from beneath the pyramid’s granite awnings.

When we reach the end of the main boulevard, Calavera stops. “My brother was a good person,” he says. “And a good ramflero.* He joined the gang really believing in the whole brotherhood thing, and when he was the leader he didn’t run when all the rest abandoned him. But I know he was sick of it at the end too. Come on, this way.” We turn down a pitted stone walkway lined with mausoleums crumbling into anonymity.

After a few minutes we walk past the mausoleum of General Justo Rufino Barrios, the great dictator and liberal reformer of Guatemala. The stone pillars are mottled green and white with mold. A giant rusted padlock hangs from the wrought-iron gate, and shards of green glass make ragged teeth in the façade. In 1885 General Barrios declared war on the isthmus to create a single great nation. He died in the first battle. Ambitions to unite Central America were buried with him. Horseflies buzz through the broken windows, feeding on rat corpses unearthed by recent rains.

“You know, it’s because of my brother that I have no tattoos,” Calavera says. “Giovanni was blue with ink. He said his body was a prison.”

“Uh, did his tattoos have anything to do with his murder?”

“No . . . well, it’s not so clear,” Calavera says. “He was the leader and the last of Los Adams Blocotes Salvatrucha. The war with the narcos took the rest. I told you they shot him on the patio of our house with an AK-47. But you see, it was only a leg wound. My sister says he was laughing and joking when they loaded him into the ambulance. But when she went to the hospital the next morning they told her he was dead. They said it was an asthma attack. Or something. Sandra—she’s my sister—thinks that maybe the doctors let him die, or overdosed him or something.”

“Where were you when all this happened?”

“I was in the orphanage in Xela.”

“Why?”

“My uncle put me there after our grandmother died. My dad was in prison, see, and no one knew where my moms was. It was my sister who buried him, and then she came to tell me what had happened. But I already knew.”

“Really?”

“Yeah.”

“How did you know?”

“Well . . .,” he says, smiling vaguely, “you might not believe me.”

“Try me.”

“Okay then. On the night he died I had a nightmare. They said I was screaming in my sleep. When I woke up, I felt this like emptiness, like something had been stolen but I didn’t know exactly what. After that, and when Sandra told me . . . well, it made sense.”

“I believe you,” I say. “I also have brothers.”

We walk down a long corridor between massive sepulcher walls stretched out before us, plots stacked in columns eight high to protect them from the rain. There are dozens and dozens of these tenements for the dead forming a vast labyrinth through the cemetery, and few signs with which to distinguish one tenement block from another. Calavera thinks Giovanni is interred in one somewhere in the northwest corner of the cemetery. We pass an old woman dressed in black, a bouquet of carnations clasped to her breast, and a man atop a wooden ladder polishing a plaque. We pass children cavorting with a puppy down the corridor.

“A few months after my brother died, my sister brought me home from the orphanage. But when I got to the old neighborhood, she was afraid for me to leave the house. She enrolled me in school, and when I wasn’t in school I was supposed to be with her, helping her little business selling tortas. I didn’t know why until a couple weeks after I was back.”

“What happened?”

“I was walking home when a bunch of kids came out of an alleyway. The war between my brother’s gang and the narco-traffickers was supposed to have ended with his death, but my sister told me that things were still crazy. We all know it never really ends. The kids started pushing me around. I was even skinnier than I am now, but quick. ‘It’s him!’ they shouted. ‘It’s true! It’s true!’ They made a circle around me. I could tell they wanted to beat the shit out of me, but they were also afraid. I saw my chance and rushed the smallest one, and he jumped away like I was a leper or something. I ran all the way back to my house. They didn’t follow me.”

FIGURE 5. Children and puppy playing in the Guatemala City General Cemetery.

“What was it all about?”

“Well, I told my sister what happened and asked her what the fuck was going on. She wouldn’t look at me, and then she started crying. ‘Some people believe that your brother’s death was fake—that he didn’t die in the hospital, and that we all hid the truth to protect him.’

“I was shocked, you know, like I was almost crying, too. ‘But you showed me his grave,’ I said to her. And my sister looked so sad. She’s tough, and I’ve only seen her like that a couple of times—when she first told me about Giovanni, and when they killed her husband. ‘They say I only buried dirt,’ she said. ‘They say it was all a charade so that he could escape.’

“‘Well was it?’ I yelled. And then she slapped me hard. I knew why. She never would have done that to me. Never, and I felt bad.” Calavera looks up into the cloudless sky where vultures turn slow spirals far, far above. Then he closes his eyes.

“So,” I say, trying to work it out, “they thought you were your brother? Or your brother’s ghost?”

“Yeah, one or the other. Or they just wanted to kick my ass because I was my brother’s brother. Anyway, soon after that I joined with Casper’s Northside crew and that sort of thing never happened again.”

We walk past a purgatory of gray concrete boxes and come upon an old man in a worn cowboy hat and fine-tooled leather boots. He slouches on a wooden stool, dozing, surrounded by half-carved stelas, protean angels, incomplete Virgins, and a rough-hewn Jesus hauling a bulbous cross. The crude savior crouches beneath his terrible load. He has no face. A mongrel of uncertain parentage is curled at the old man’s feet. Their eyes snap open as Calavera and I draw near. Without moving, the old man tracks our progression. We nod and say good day, and he nods. The dog sniffs the air before curling once again into its tail. The man picks up a marble plaque and after studying it briefly, lays it across a palette nailed between two wooden horses and begins polishing it with a bit of rag. I have a passing vision: the blank headstones and plaques etched with the names of dead friends, informants, and murder victims I read about in the newspaper. Maria Siekavezza. Juan Carlos “Chooky” Rodriguez. Maria Tzoc Castañeda.

FIGURE 6. A mass grave in the Guatemala City General Cemetery.

We turn right onto another long, straight corridor. Bright flowers and succulents grow in plastic planter boxes garnishing the cubbyholes of the dead. Solemn, washed-out portraits return my gaze. A young man with a goatee and shaved head, stained blue with rain and time, poses grimly in a dark suit. A girl child smiles, one hand raised as if in greeting or farewell, from beneath a carved elegy. The wall rises up twenty feet, and many of the cubbyholes are covered over in rough plaster, service numbers scrawled on them in black paint. Others are empty and open, mortar and broken brick, here and there a scrap of faded crinoline. They await the newly deceased to replace those whose families have stopped paying their cemetery dues. Each day cemetery workers haul away the desiccated remains of the indigent dead in wheelbarrows and toss them down a forty-foot hole where the cemetery borders the ravine of trash. Here, at the cemetery’s outermost edge, nature too takes part in erasing the past. Each year, as the rains wear away the earth, one by one the abandoned mausoleums and broken sepulchers tumble down the muddy slope to mingle their remains with the refuse of the metropolis.

* Gang leader.