Читать книгу Mortal Doubt - Anthony W. Fontes - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Portrait of a “Real” Marero

Guatemala City, May 2012. A few days after Calavera and I met in the cemetery, I found myself sitting across from a young man slouched in a desk chair in the corner of a prosecutor’s cluttered office.

“What can you give me?” he asked. He had a wispy mustache and smooth, olive skin, a Miami Marlin’s baseball cap pulled over long black hair tucked behind his ears. The sliver of a roughly etched tattoo on his chest peeked out from under a short-sleeved button-down.

“Not much,” I said. Having grown accustomed to this question, I was careful not to promise more than I could fulfill. I repeated an offer I had made to others. “I can tell your story far from these streets where you have seen so many like you die.”

He gazed at me silently for several seconds and then nodded. “Right on (Órale). Ask me your questions. You ask and I answer.”1

So began my first interview with Andy, a seventeen-year-old member of the Mara Salvatrucha (MS) and protected witness for the Guatemalan government. After more than a year of living and conducting fieldwork in Guatemala City, I had gotten to know many young men caught up in gang life, like Andy, and many more struggling to leave gang life behind. But few were able—or willing—to tell about their lives with such clarity and detail, and none were in quite the predicament in which Andy found himself. Since the age of eight Andy had extorted, killed, and tortured for the MS clique Coronados Locos Salvatrucha (CLS) the most powerful clique of Guatemala’s most-feared mara. As a protected witness in the prosecution of gruesome murders he claimed to have helped commit, he crisscrossed the blurred boundaries dividing the “criminal underworld from the law-abiding world that rests upon it.”2 Straddling the uncertain divide between a weak, corrupt judicial system and the criminals it is meant to bring to justice is dangerous business. When we met, Andy seemed to be making a stand against—or at least reconsidering—the brutal realities that had shaped so much of his life. But whatever personal transformations he might have been experiencing were cut short. A little over a month after our first interview and three days after our last, the MS found and executed him.

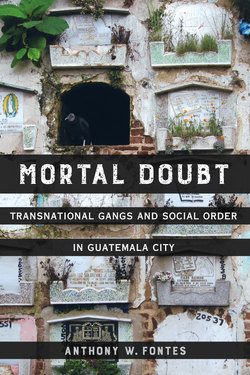

FIGURE 7. Andy, protected witness for the Guatemalan government, May 11, 2012.

Before he died, Andy gave Guatemalan investigators detailed testimony describing his gang’s modus operandi, their strategies, and the motives behind unsolved murders both mundane and spectacular. Through our conversations I tried to record his history and map out his beliefs and reflections about the world he grew up in and his current predicament. Oral histories are inherently unstable, always “floating in time between the present and an ever-changing past, oscillating in the dialogue between the narrator and the interviewer, and melting and coalescing in the no-man’s-land from orality to writing and back.”3 The conditions of Andy’s life, the circumstances of our encounter, and his violent death place his story in the most volatile and treacherous zone of this “no-man’s-land.”4 Threading it together requires pivoting back and forth among Andy’s recorded voice; the memories, myths, and fantasies it invokes; and the fact that he is gone.5 His is a story shot through with lacunae and ellipses. Perhaps if he had lived, I could have distinguished more truths from untruths. But this confusion is in a sense precisely the point. Such a fractured narrative is entirely appropriate for a tale of violent life and death. Andy’s story is about how a young man survived and learned to use violence. It is also about how this violence dictates how that story can and should be told. The complex interplay between truth and rumor, the facts of the matter and the inventions of the imagination, illuminate the possibilities and pitfalls of the search for order in the midst of chaos.

Both the real and imagined violence of Central America’s gangs makes delving into the gang phenomenon extremely difficult, for at least two reasons. First, as gangs have become more insular and more violent, getting past collective fantasies about them by getting “close” enough to gang-involved youth has become far riskier. Second, such fantasies are deeply a part of gang culture itself. In twenty-first-century Central America, maras have become erstwhile emissaries of extreme peacetime violence. They have come to distill in spectacular fashion the fear, rage, and trauma swirling around out-of-control crime. Young mareros like Andy are drawn in by and work hard to re-create the phantasmagoric figure the maras cut in social imaginaries, linking the acts of violence gangs perform to the ways gang members (and others) collectively and individually make sense of this violence. This entanglement between symbolic meaning and material violence was starkly illuminated in Andy’s courtroom testimonies. Even as he engaged in flights of fantasy, his testimonies provided the locations of real cadavers, decapitated and quartered, and revealed in precise detail acts of violence no more gruesome or farfetched than the deeds he claimed as his own.

By the time I met him, Andy had become expert in playing the part of the “real” marero, a patchwork figure sewn together from the facts, fears, and fictions swirling about criminal terror. In drawing an image of himself for me, he seemed to swing back and forth between self-consciously acting out this role and searching for some alternative means of representing his life. I will not—I cannot—parse truth from fantasy. But neither do I wish to simply reproduce and reify the fetishized spectacle of gang violence that seemed so integral to Andy’s sense of self.

Instead I follow Andy’s lead. Since he seemed to fold fantasy and experience so seamlessly in his narration, I have written this account of Andy’s life and death in a similar vein. I will not arbitrate between the truth of his stories and the lies, half-truths, and flights of fantasy. By walking in Andy’s footsteps I show how his forays into fantasy cannot be understood as solely his own. “Men do not live by truth alone,” writes Mario Vargas Llosa, “they also need lies.”6 The fiction of the “real” marero Andy worked so hard to fulfill also served the needs of those who would use him for their own purposes and who in turn take part in the layering of fantasy into Andy’s tales. These exchanges—between gang leader and gang wannabe, investigator and witness, writer and subject—illuminate how essential shared fantasies and falsehoods are in the production of knowledge about criminal terror, as well as in the making of violence itself.

ANDY’S UTILITY

A month before I met Andy, I climbed the fifteen stories of Guatemala City’s Tower of Tribunals. I went to court to witness the sentencing of Rafael Citalan, a twenty-three-year-old guero (light-skinned man) with slicked-back hair and a jutting chin. He was one of several MS members allegedly responsible for murdering four people, decapitating them, and placing the heads at various locations around Guatemala City. He sat in chains in a glass and metal cage, wearing a white T-shirt, jeans, and plastic clogs, head bowed before his own reflection. As the judge droned out a long list of his crimes, pronounced his guilt, and handed down his sentence in minute detail, Citalan kept shaking his head.

Back in June 2010, incarcerated leaders of the MS had ordered gang members on the street to decapitate five people. In the end, one clique failed, and they only managed to kill four. Gang members placed the four victims’ heads at various locations around the city. With each head they left a note—supposedly written by Citalan—attacking the government for “impunity” and “injustice” in the prison system. Media outlets across the country flocked to publicize the grisly affair.

Before the trial, I’d spoken with Edgar Martinez, the lawyer for the prosecution. He is a tall, balding man, amiable and ready to talk. “This is the most spectacular and frightening gang case I have been involved with,” he said. “This was a political act. They wanted to terrify the populace and intimidate the government so they would get better treatment in the prisons. It’s the first case I’ve worked on that has had such political overtones. It’s like terrorism.”

For nearly two years the crimes remained unsolved. Maras are notoriously difficult to infiltrate. “They have their own language, their own style,” said an eager young Guatemalan gang expert working with an FBI task force. “It is their subculture that makes them harder to infiltrate than even organized crime or drug traffickers (narcos).” Besides, as they have admitted to me time and again, Guatemalan security officials have very little experience in undercover operations. Martinez told me that the case broke open with the testimony of a secret witness, another MS member who, for reasons he did not explain, confessed and turned on his compatriots. This witness, I would learn later, was Andy.

“He’s really something. He’s a real marero,” exclaimed Martinez, his eyes wide with excitement, while we were sitting over fried chicken, his bodyguards sitting stolidly beside us. “And a good witness. A fine witness.”

The only reason Andy seemed to matter to Martinez and nearly everyone else with whom he worked was his utility. For the government prosecutors reveling in his authenticity, he made possible a deeper understanding of the MS than they had ever had. Guatemalan investigators are often woefully ignorant regarding the criminal structures they face, making a “real marero” witness like Andy a rare treasure indeed. A paranoic state and terrified society have long targeted poor young men who happen to have tattoos, wear baggy pants, or use certain slang as potential mareros.7 And the illicit businesses in which gangs are involved—extortion, drug dealing, hired assassinations—incorporate people and networks far beyond the gangs themselves.8 The maras are not a discrete “thing” separable from structures of violence linking, among others, organized crime, poor urban communities, and corrupt state officials. Distinguishing living, breathing mareros from their brutal public image reproduced in the media and everyday conversation is also difficult.9 Gangsters and gangster wannabes alike work hard to mirror the monstrous figure the marero cuts in the collective consciousness. Yet more often than not, both the victims and alleged perpetrators of “gang violence” are not even gang members.10 Andy, however, was. He also had a remarkable memory for detail and was able to provide an accurate insider’s perspective on how the MS operates.

The gleam of excitement in Martinez’s eyes when he touted Andy to me—“a real marero!”—spoke volumes. By giving the government the case of the four heads, Andy offered prosecutors a chance to show they were not the corrupt, incompetent bureaucrats most Guatemalans believe them to be.

But even as Andy helped prosecutors take apart the Mara Salvatrucha’s most powerful clique, the government failed to give him cover. Andy’s murder only months after helping investigators break open one of the most sensational mara cases in history epitomizes the state of justice in Guatemala today. As part of the witness protection program, officials locked Andy and three other gang associates who had followed him into exile in a room for three days with little food. The stipend money they were promised never materialized. When the boys complained, no one listened, and when they complained more loudly, officials kicked them out of the program. After Andy’s death, Federico, a young, earnest investigator who had taken Andy under his wing, waved a sheaf of papers in my face. “These are applications to get him back in the safe house,” he said, shaking his head. “All rejected. He hadn’t even begun to give us 1 percent of what he knew.”

When I met Andy, he had already been kicked out of the witness protection program and was seeking his own security by joining a Barrio18 clique. From our very first encounter, I did not need to cajole Andy into telling me about his life—he readily agreed to my using a voice recorder in each of our interviews—but that does not absolve me from having used him as well. I am using him now. When Martinez mentioned the possibility of meeting him, I jumped at the opportunity. “A real marero!” While my reasons for wanting to meet Andy were distinct from the government’s, I shared a similar dilemma. Reliable informants were hard to come by and harder to keep. Throughout my fieldwork, my network of people involved in criminal groups was in constant flux. Friends and contacts were transferred into maximum security prisons, were killed, or simply disappeared. I was careful to keep my correspondence with Andy—and his situation—secret from my networks in prison. I confided only in Calavera and gave him no details. He warned me in no uncertain terms that Andy’s cooperation with the government would get him killed. Still, although I pursued Andy, at the time I did not realize just how short-lived our relationship would be. It took a couple of weeks of repeated phone calls to Federico to finally set up an interview.

Federico introduced me to Andy as an American (gavacho) scholar who wanted to learn about gang life. I emphasized that I was not a cop, nor did I have any connections to law enforcement, but was merely a researcher and writer with no stake in the struggle between the Guatemalan government and the gangs. Careful not to promise more than I could fulfill, I never pledged more than to write his story. In retrospect, however, even this paltry promise may have shaped how he chose to represent himself. Did he improvise and edit his tale to match what he imagined would keep me coming back for more? He already knew that his usefulness to the government was all that kept him out of prison. He was used to being used. Before I used him for my research, before the government used him to take apart the Mara Salvatrucha, gang leaders used him to commit many, many murders. Children who kill do not risk the same legal consequences as adults. For years his usefulness kept him alive when everyone about him was dying. And a week before his death, Andy fantasized that he was using the government to wipe out his enemies.

“More than anything . . . look, I’ll explain,” he said. “What I want is that they catch all those assholes so that I remain as the commander. To govern, you understand! Once I’m in charge it’s gonna be another deal, loco (dude). No more extortions. . . . Well, there will be extortions, but you won’t see any deaths. We’ll go to the homes and tell them, ‘Look, we’re going to take care of you, but we don’t want the violence.’ To reach an accord without the violence.”

At the time, I shrugged off this declaration as so much brash naïveté, the foolish musings of a young man. In retrospect, I was blind to just how skilled Andy had become in bending his words to manipulate those around him, including me.

FINDING AND LOSING ANDY

I did not fully comprehend while he was alive just how precarious a position Andy was struggling to maintain, nor all the roles he was playing at once. He was a protected witness against the MS while undergoing initiation with their rival, the Little Psychos, a powerful Barrio18 clique, in another part of the city. He was saving his skin from prosecution for quartered corpses dumped in front of his house while claiming revenge against the MS for killing his family, who were Barrio18 members.11 Andy would brag about killing enemies and innocents and in the next breath be cursing his old clique for hurting children. The complexities and contradictions of his life only came into focus as I pieced together what I could from our recorded interviews and the transcripts from his court testimony.

Take, for example, the constellation of aliases he used in his short life. Andy, aka El Fish, aka El Niño, aka El Reaper, aka José Luis Velasquez-Cuellar. Each of his names addressed an aspect of his self and his history. He said that before she died, “my mother called me Andy,” and that’s how he introduced himself to me. When he was a toddler his neighbors and family called him El Fish because of a funny hairstyle he wore for a time. “They called me El Niño because I was the youngest ‘homito.’” Homitos are little gangbangers, who emulated the Barrio18 members who controlled his neighborhood before MS killed them all. When he was a gang wannabe trying to pass his chequeo—an initiation period in which the gang measures a wannabe’s worth—with the MS, “they called me El Reaper [as in the Grim Reaper], because I collected the most lives,” he said. He claimed they also called him El Enigma, because they could not fathom his true desires. To the legal system and the press, he was Jose Luis Velazquez-Cuellar.12

I have kept two pictures of Andy. The first I took at our initial meeting in the public ministry building. Federico had introduced us perhaps an hour earlier. In the photograph Andy looks into the camera without expression—no smile, nothing—as if he were looking through me. I had asked to see his tattoos, and he lifted his shirt up to his skinny shoulders, exposing his chest. There were two: a gaunt female face wreathed in flames and a roughly etched marijuana leaf. The latter I have seen many times. It is a popular “subversive” symbol among disaffected Central American youth.

“My first tattoo,” he said with pride. “I got it when I was eight.”

“And the other?”

“My mother. They shot her eight times.”

The second photo was taken about an hour after he was gunned down with five bullets to the back of his skull. It’s a grainy, black-and-white image snapped by the police who retrieved his body a few blocks from the McDonald’s where we had our last interview. Andy is lying on his back, eyes staring off to the right, lips parted, exit wounds swelling the left side of his face. A triple slash across the front of his black sweatshirt looks at first like some brutal injury, but on closer inspection is merely the trademark logo for Monster Energy drink. Monster Energy . . . the irony is just too much. Federico gave the photo to me along with the rest of the police report on Andy’s murder. “Here, do something with this for your book,” he said. “Don’t let him be forgotten.”

A month before his murder, Andy said he knew he must die. “Anyway, I don’t give a shit. I’m already dead. I lose nothing. When my time comes, they better come at me from behind, because if not . . .” And this was precisely what they did. “These are my streets,” he had said to me as we walked out of the McDonald’s into the five o’clock sun hanging low over the concrete boulevard where his body would be found. He wasn’t looking, but he must have known they were coming. An hour earlier they’d taken out his friend, El Gorgojo, a fifteen-year-old kid who was often slouched in the corner of the prosecutor’s office to support Andy while he made his declarations. Gorgojo had followed Andy into exile when he left the MS, so he would share his fate. After they shot Gorgojo, Andy called Federico.

“They killed my carnal (buddy). They killed Gorgojo.”13 He was sobbing.

Federico told him to go home, but Andy kept repeating, “They killed him, those sons of bitches. He never did anything to anybody.”14

The phone went silent midsentence, and Federico heard no more from him. It seems as though Andy’s concern for his friend was his undoing. Gorgojo’s killers had seen him in the crowd milling about the body. Perhaps killing Gorgojo was simply a ploy to draw Andy out of hiding. An hour later Andy, too, was dead. That’s when Federico called me at home. “I have bad news for you,” he said. As he spoke, I pictured him sitting in his office, linoleum floors cluttered with case files, requests for Andy’s reentry into the protected witness program stamped “denied” and piled in a cardboard box. And I already knew Andy was dead. Of course he was. Federico sounded terrified. “He told me they’re going to come for me, too,” he said. “They have videotapes, he said. They know my face and they know where I work.”

I told Federico to be careful, and then there was nothing else to say. We hung up, and I slumped back in my shoddy wooden chair in my barely furnished apartment. Stupid boy, I thought, and clutched my belly and cried, but only for a few seconds.

BECOMING A REAL MARERO

This is how Andy said he came to join the MS. He grew up in Ciudad del Sol, Villa Nueva, an urban sprawl bordering Guatemala City’s southern edge. His parents were both Barrio18 gang members. He never knew his father, but his uncle was of the “Clanton 14,” one of Los Angeles’s original sureño gangs that still has mythological status among Barrio18 folk in both US and Central American cities.15 Andy started with Barrio18 when he was just six years old, and he said he was leader of the homitos, the little homies, the gangsters in training who hung around their older, bloodier brethren. When Andy was eight the MS clique CLS—led by El Soldado, a man who would become nationally famous before he died at age twenty-three—captured Ciudad del Sol in a hostile takeover. Andy’s mother was shot eight times and died a few days later, and they killed his uncle with a gunshot to the head. So, Andy said, at eight years old he decided to go on a mission to infiltrate the MS clique that had taken out his people. He joined with a plan to bide his time and kill those who had killed his family. At least this is what he told me after he’d become a government witness. I was never sure whether he was trying to justify—to me or to himself—betraying his gang. I suspect the truth was rooted somewhere else, somewhere deeper and too painful to admit. I believe that after making Andy an orphan, El Soldado took him under his wing. The Coronados killed off his family and then replaced it.

FIGURE 8. Andy, June 20, 2012. Photo: Anonymous.

I asked him what the MS meant to him while he was still part of it.

“It was a family that didn’t leave me to die,” he said. “When I needed it most they gave me a hand and gave me food to eat, you understand. So I couldn’t bite the hand that fed me.”

“So they were your friends?” I asked.

“Not my friends. They were family,” he insisted with what strikes me now as ineffable sadness. “They were my family when I had no family. It was all I had. I had no father, no mother, no brothers or sisters. They were my family.”

With no one to turn to except the very authors of his disaster, eight-year-old Andy had to reconcile insuperable emotional contradictions. Rendering the ordeal into a simpler story line such that his eventual betrayal became a successful conclusion to a tale of righteous revenge ties up the loose ends quite elegantly. In this version of his history, both Andy’s past and present selves retain agency and control that one suspects were absent in his “real” life.

In any case, he said that for years he couldn’t get his revenge because they knew where he came from and kept him closely monitored. He underwent a particularly long and strenuous chequeo—a period in which the aspiring gang member demonstrates his worthiness—being tested with ever more difficult missions. When he was nine, he said, already a year into his chequeo, he had to kill another kid who had tried to run away:

They dropped the kid from chequeo, and for his failure they were going to drop me too. It all went to shit because of this dude. He took off and was in a discotheque here in zone 5. He never imagined that I would come to zone 5 to find him, and I came, and another homie came with me. He was like, “Look at (watchea) that dude, look alive and go hit him.”

“Son of a (a la gran)!” I said. “No way bro, the dude backed me up (el vato me hizo paro).”16

“What do you mean ‘no’ you sonofabitch,” he said, and he got on the phone with the chief, El Soldado. “Look, Soldado,” he told him, “the vibe (la onda) is that the Reaper doesn’t want to hit Casper.”17 And then he turned to me, “Look here you sonofabitch, if you don’t shoot him I’m gonna shoot you.”

“A la gran, okay,” I answered, and so I had to shoot the guy. I shed a tear because he was just a baby. I still had a heart, you know. Since then they showed me how to not have a heart, so I didn’t have feelings about anything.

This was Andy’s first murder, and given the circumstances, it seems that killing the boy was a matter of self-preservation. This was the “choice” Andy’s victim had refused to make by running away, a move the gang interpreted as a decision to die. How does a nine-year-old make sense of such a brutal zero-sum calculus? Age-old philosophical puzzles—the parsing of guilt from innocence, for example, or the possibility of rational choice and free will—become moot, even absurd, when applied to the moment in which Andy took the gun too heavy for his thin wrists and shot another child.

When we spoke, Andy blamed El Soldado for making him into a killer. Like Andy nearly a decade later, the CLS chief would die while apparently cooperating with the government to reduce gang violence in Guatemala City. The reasons for his death remain unclear to all but those who ordered it. El Soldado had played some very dangerous games: becoming a lead negotiator with the government to start gang rehabilitation programs and meeting with and giving talks to the police, the media, and low-level government officials in which he advocated the need for reconciliation, that gangs could be part of peacemaking, and that police profiling was violating poor youths’ human rights. His message made him both a celebrity and a target for other gang leaders (and as the rumors go, for the police as well), for whom gang war was far too profitable to give up. For a short time, national media referred to him, with thinly veiled sarcasm, as the next “savior of Guatemala” for his role in trying to bring peace to the streets.18 A few years before he died, an Associated Press photographer snapped his picture hunched over his baby son at his home in Ciudad del Sol—the neighborhood where Andy’s family once lived—kissing the child’s head and holding a .45.

El Soldado’s celebrity made him the very personification of the MS and all its contradictions. The savior of Guatemala was, according to his contemporaries, also a central player in institutionalizing the practice of descuartizamiento (dismemberment), torture, and other forms of extreme corporal punishment against captured rivals as well as homies who betrayed the gang, wanted to leave, or couldn’t cut it anymore. This kind of violence is performed in a group, a communal act in which aspiring or newly initiated members must take part to prove their mettle. Andy said he participated in a descuartizamiento for the first time when he was ten.

FIGURE 9. El Soldado and his son in front of their home in Ciudad del Sol, Villa Nueva, in 2003. Photo: Rodrigo Abd (API).

“I had to kill a homie from my old barrio (gang).19 We had to dismember him, just me and the ramflero (gang leader).”20

“You had to kill and quarter him?”

“Nope. Dismember him alive. Torture him, make it a party.”

“Where did this happen?”

“Over in Ciudad del Sol, Villa Nueva in a chantehuario. Chantehuario, that’s what you call the houses of war, you understand, where all the homies will be, see.”21

“Were the others around when you were doing it?”

“Yeah. All the homies of my clique: El Extraño, El Huevon, El Shadow, El Brown, El Maniaco, El Delincuente, El Fideo, El Aniquilador, El Hache, El Chino. All of them, you understand.”22

“What were they doing?”

“Marking the wrath (marcando la ira), seeing if I had heart, mind, and balls. All they ask of you in the Barrio is that you have mind, heart, and balls, because if you don’t have any of them you’re not worth dick. That’s right, and I had been a little vato since I was six with Clanton 14. Now they were seeing what I was capable of, testing me. So with faith and joy I had to do it.”

“How did you feel?”

“Look, carnal, the way I grew up, I grew up in the gang. My dad was eighteen, my mother was eighteen, you understand, ok. I had already grown up with a gangster’s outlook, so I took pleasure in killing dogs, going around killing cats. So when I killed a human it was like I was killing an animal. I was already a beast (bestia) for that kind of thing.”23

I still find it difficult to stomach Andy’s glib reproduction of himself as beast, as the devil personified. I wanted some other explanation—something more nuanced and reflective, perhaps. But none was forthcoming, at least not from him. Again and again, he claimed the virtues of a “real marero.” Whether he in fact embodied this image and did so out of habit or was simply playacting is impossible to say. The idea that mareros are essentially different from other criminals, and from other human beings, is an important part of their public persona. It is also a notion the maras have taken on and self-consciously cultivated. The key distinction, the way to “recognize” a marero, is his capacity for violence without the psychological baggage that would paralyze a “normal” human being.

In our last meeting, Andy sat across from me in a McDonald’s, a chicken burger and fries untouched before him. Middle-class parents eyed us nervously while their children shrieked in the ball pit some thirty feet away. “Human beings have five senses,” he said. “The marero will have a sixth. The sixth will be that he has no heart, that he doesn’t give a damn about anything. You will dismember for your gang, you will kill for your gang, you will die for your gang. This is how you describe a marero.”24

It was as though he was reciting from a script. The cadence was measured and precise, with emphasis on the action verbs: descuartizar, matar, morir (dismember, kill, die). He seemed to be describing a sociopathic subject freed of the empathies expected of “normal” humans: for others’ suffering, for the value of human life, for the need to be considered human at all.25 “I am more than human,” Andy seemed to be saying, “because I am less.” To identify so closely with the inhuman, the beastly, the demonic is to reject all facets of belonging in wider society—worldly, spiritual, and otherwise—since “one’s worthiness to exist, one’s claim to life, and one’s relation to what counts as the reality of the world, all pass through what is considered to be human at any particular time.”26

Such wholesale alienation cannot be invoked with mere words. It must be created through ritual and repetition. The urge to fetishize the violence of Andy’s world is strong: to hold it at arm’s length and convince oneself that it is not ours, it belongs to some other realm, some other time, some other species. I know. I have done it. The image of grown men performing similar acts—in a war zone under military orders, perhaps—seems to me more palatable, or at least less world-rending. Children who kill, children who learn to glory in death, embody an ethical and even existential set of dilemmas for human societies. They invoke a deep-seated sense of horror, an internal scream pleading “How could this happen in the world I live in?”27 And yet by reacting this way, we ignore how children like Andy learn to do what they do through an education. Andy’s life demonstrates how this behavior is taught. Accepting this fact means accepting that any one of us could be molded in exactly this way.

Through the brutal acts the MS made him perform, Andy made himself in the image of the unfeeling killer that mareros are so widely imagined to be. He became not only a child who has killed, but a child who assumes he must be a killer in order to be anything at all. Once he was caught up in this image of himself, all possibility of a different life and a different way of being seemed to disappear. But at least some of his brutal braggadocio was pretense. Several times Andy seemed to let slip the suffering hidden behind the facade of the unfeeling killer, admissions quickly swallowed back again.

“I’m already grown and I’m always shedding tears, loco,” Andy said the last time I spoke with him. “Because one knows that loneliness attacks, and one has a heart. Maybe not for caring for other people, but for caring about oneself. . . . To not have a person who will listen to you, to be able to talk and have a peaceful life. . . . But whatever, it’s the life that I chose and so it has to be cared for.”

“Chose?” I asked. “Do you think at the age of eight you can really choose?”

“Like I said, I didn’t know the deal then.” He shrugged. “I didn’t know what I would get myself into. But here are the consequences, you understand, and I’m grown. All that’s left to me is to tighten my belt and continue forward, with my chest high. This is what destiny wants.”

“Would you say you were a victim?”

“No way, I’m no victim. No way, carnal.”

“A victimizer then?”

He paused for a moment, and then laughed uncertainly. “That’s it. Other people are my victims.”

Andy’s outright rejection of victimhood sutures him tightly to the carefully nurtured and hyperaggressive machismo typical of the maras. But refusing the mantle of victim, to my mind, only reifies his victimhood. His stubborn insistence on his own agency required turning a blind eye to the lifetime of brutal exploitation that he had survived until then, not to mention the complex assemblage of violent structures and structural violence that framed his life.28

Upon reflection, however, my urge to think of Andy as a victim may very well stem from my need to empathize with his dilemma and so bridge what too often feels like an insuperable divide between my perspective and his. I cannot deny that I was, to borrow a phrase from Antonius Robben, “seduced” by Andy’s being a “real” marero, drawn in by his eloquence and bravado before so much risk and violence. Over the years of writing and contemplating Andy and his fate, I have gained a modicum of distance from this seduction, but it was woven into all our conversations and still shapes how I convey his story to you. Andy and his story can only emerge through the lens of my recollection and reflection, warped by my own sentimental image of his life and death.

KILLING INNOCENCE AND BEING SOMEBODY

Before Andy entered adolescence, he was accustomed to killing. Once accustomed to killing, he claimed, the distinctions between the “innocent,” the relatively sacrosanct, those-who-deserve-to-live, and those who do not all but disappeared. In his short life, Andy learned that the categories of innocence and guilt and right and wrong cannot be and never are stable.

As Andy grew from a child into an adolescent, gang war in Guatemala intensified, and CLS expanded from the territory in Ciudad del Sol won from its rivals to running extortion rackets in La Paz, El Alyoto, Linda Vista, and numerous other neighborhoods. It became the dominant gang in Villa Nueva. Its success was underpinned, at least in part, by turning the violent techniques used against enemies and traitors onto extortion victims residing and doing business in its territories.

In conversation with me, Andy made no distinction between innocent victims and enemy combatants. When I asked him if it was difficult to kill people who posed no threat to him, he replied, “No way. It was a luxury for me. It was a luxury to go killing people, go collecting. In the clique we had this thing of seeing who would kill more people. So every day we would go. One day I would kill two and another guy comes and he’s killed three.”

“So it was a competition between you?”

“Exactly. It was ‘who’s the best?’ The best sniper, you understand. That was the game.”

“What type of arms did you use?”

“Guns. M16, AR-15, 9.40, 380, 357,” he said, ticking them off on the fingers of one hand. “Whatever there was, even machetes, to use to take a person’s life when the time came.”

He claimed this was his expertise. Not for nothing, he said, did they call him El Reaper. He was for a long while one of the youngest in his clique, and as the youngest he was often given the dirtiest jobs. El Soldado and those working beneath him knew that the police could do little against a child. Another member of the MS serving multiple life sentences recalled getting hauled in a half dozen times as a minor for homicide. Once a policeman jerked him by the handcuffs off the pavement, muttering, “Just wait ’til you’re eighteen, you son of a bitch,” while the boy grinned in his face. Andy said the police picked him up a few times, but no witnesses ever came forward to testify against him, and he never spent more than a few days in police custody before the charges were dropped for lack of evidence.

Andy hurt and killed his share of victims, but no matter what he said, he certainly was a victim himself. But for Andy, and countless others caught up in such violence, an act of killing can be about far more than simply ending another’s life. The most cogent summary of what death and violence does to and for boys like Andy came from another MS member named Mo. “This world is not like your world,” he said in a quiet voice, sitting in the prison yard, staring at his hands. He had been incarcerated for over a decade, and with forty years left of his sentence, would likely die in prison.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Here death plays into so many social necessities, to your very identity, that it becomes an addiction—addiction to the money, the pleasure of it, but it’s a pleasure that comes from the respect you get, from your name entering the myth of the street. This is the way to be somebody—but as you build up your name on the street you are also building up your own prison, because the bigger you become the more of a target you become. And then you’re only thinking that if they do come to kill you, they shoot you in the head. That’s the best way out.”

Money and addiction, myth and identity, pleasure and death are hopelessly entangled when hurting and killing become the ultimate means of fulfilling a sense of power and importance.29 Encoding oneself into the myth of the street means becoming one more rider of the self-consuming Ouroborous, taking a trip on the never-ending cycle of death and revenge that gang war has become.30 Among mareros, killing, and making sure the world knows you are a killer, have become key to being somebody.31

And yet the telling is never an exact copy of the doing. The entangled causes and conditions that drive a person to commit a violent act, or any act for that matter, are not the end products of some rational choice game. Pressed to explain himself, Andy supplied a coherent narrative, a chain of events that made the act inevitable. For gangsters like Andy the act of killing—to choose who lives and who dies—has to seem like a choice, but it is precisely because violence becomes a point of pride and the fodder of myths that the excessive brutality so many mareros claim as their own must remain suspect. If the circulation of personal myths, if being somebody, is a key aspect of why mareros kill, then stories of killing may simply be the raconteur’s fantasies grown from the desire to reflect this brutal paradigm.

THE REAL, THE TRUTH, AND THE DEAD

How do we provide accounts of ourselves to others? What do we expose, and what do we keep hidden? And how do the stories we tell about ourselves entangle what we have done with how we imagine ourselves to be?

These questions hinge on the complex relationship among agency, event, and acts of narration that materialize the event in the moment of its (re)telling.32 That is, no event is accessible outside of its narration; nothing that happens has any meaning separate from how it is “remembered, recounted, and mediated.”33 This means that an event’s existence does not remain locked in linear time. Its temporal contours shift each time it is narrated. What’s more, this intimate entanglement between the doing and the telling also constitutes an essential process in how people imagine themselves to be, in the very making of the subject himself. The narrator is as much a product of the story as he is its purveyor, and in the moment of telling he reinvents his own place in the world.

For Andy, the ability to reinvent himself by performing carefully crafted narrations of self was always a matter of life and death. He struggled for years to pass his chequeo and become a bona fide homie of the Mara Salvatrucha, to show his gang that he was really one of them. Playing the role of the real marero had become his life’s work and key to his survival. But how much of his narration was self-conscious performance reciting the experiences a “real” marero ought to have? That is, if Andy understood me as a conduit through which his story might live beyond his particular place and time, then what was invented to fulfill the image of the spectacular real?

One often-repeated “truth” is that no one escapes the MS. The exit routes once open to Central American mareros—having a kid, going straight, becoming a devout Christian—have crumbled in the face of heavy-handed policing and society’s unwillingness to forgive mareros’ tattooed skin and stained souls. Andy mouthed the words he had heard hundreds of times: “You can run, but you can’t hide.” Years before, El Smokey, the CLS leader before Andy became part of the gang, had run to the United States. Andy said El Pensador, the man who took control after El Soldado died, issued the order to have El Smokey tracked down and killed.

This was in 2006. The SUR, a prison pact between Barrio18 and MS, had been broken the year before, and it was a new, harsher world. Former mareros, labeled “Gayboy Gangsters” and pesetas (meaning “pennies,” because they aren’t worth a damn) by their old comrades, who had slipped away in the preceding years, would no longer be so lucky. “The culero (faggot) who runs gets a green light. Period.” A green light is like the mark of Cain. A message filters out via cellular phone and word of mouth among every clique in the country, ordering execution. Every homie, chequeo, and gangster wannabe has the duty to shoot the person on sight. This is why Andy said El Smokey had run to the North, to escape the web that surely would have ensnared him had he stayed.

As the story goes, El Pensador wanted that loose end tied up. And so in 2007 he sent Andy, along with a boy named El Pícaro, to kill El Smokey. Andy had been in chequeo for almost four years due to his young age and suspicions that he might still have loyalties to his Barrio18 roots. “If you want to end your chequeo, go find that son of a bitch and kill him. That’s your mission,” the ramflero told Andy. The homies in Guatemala knew El Smokey had gone to Los Angeles. According to Andy, it was his women who gave him away.

This is how Andy described the journey: on their way north, he and El Pícaro, newly minted missioneros, passed from clique to clique across the Guatemalan border and into Mexico. From Tecun Uman they crossed the Suchiate River in a truck driven by Mexican MS members. They then traveled up to Veracruz, Mexico, and so on, always escorted by a local MS member who knew the area and could navigate the local authorities, always checking in with El Pensador back in Guatemala, who dealt with the local Mexican clique, ensuring the two boys had food and money. It took three months to complete the trans-Mexico journey and enter the United States.

When Andy and El Pícaro caught up with their target in Las Vegas, some local MS homeboys pointed him out and gave Andy a knife. El Smokey was wearing a turtleneck to cover the MS tattoo etched in gothic letters across his neck.

“They told me, ‘Look at him, that’s the dude over there. Hit him here and he’ll die slowly,’” touching his belly. “‘Hit here and here and he’ll die instantly,’” touching his neck and his temple. “One time, bimbim!”

“Do you remember where you were?”

“In front of a casino. I hit the guy and he went like this.” Andy clutched the right side of his neck. “He took a half step, and boom, he fell. When I left there was a helicopter, tatatatatatata.”

“What kind of gun did you use?”34

“No man! Over there you use a knife. Like I told you, we didn’t have permission to take him with bullets. It was a place of real cops (mero juras) so finfinfin!” He stabbed the air with an imaginary knife. “So he was just left there. That’s right. It was a job for the gang (barrio).”

El Smokey died from the knife wounds in the neck he had tried to conceal, in front of a Las Vegas casino. At first the passersby thought he was fallen-down drunk, a common enough sight in that city. Andy’s mission accomplished, he returned to Guatemala and finally ended his long chequeo. At least this is how he recounted the story to me a few days before MS murdered him.

A month after Andy was killed, I finally got around to watching the film Sangre por Sangre (the English title is Blood In, Blood Out). It is a fictional account of the birth of the Mexican Mafia—a Mexican American prison “super gang”—in Southern California prisons, written by Jimmy Santiago Baca, an accomplished ex-con writer and poet who found his muse in the early years of incarceration. The film—produced and distributed by the Walt Disney corporation—can be found all over Mexico and Central America. I bought a pirated copy in a Guatemala City market. Alongside American Me, it ranks as one of the most popular and “accurate” film accounts of the Mexican Mafia, which to this day holds sway over Latino street gangs like 18th Street and the MS in Southern California and parts of the US Southwest. I watched it alone in bed, drinking a beer.

A third of the way into the film, the main character, Miklos, a half-Caucasian, half-Latino youth desperate to join the prison gang “La Onda,” must demonstrate his worth by killing a white prisoner who has double-crossed the gang. “Show him the book,” the gang leader tells a tall, mustachioed prisoner named Magic. The book looks like a small, black Bible, but hidden in its pages is a human figure marked with black dashes. The dashes are kill points.

“Hit a man here and here,” says Magic, pointing to the stomach and the chest. “And he will die slowly, painfully. Hit a man here or here,” he continues, pointing to the neck and the head, “and he will die instantly.”35 I rewound the scene and watched it again and again. Astounded. Angry. Laughing in confusion.

Did Andy see Sangre por Sangre? Did twelve-year-old Andy travel all the way to Las Vegas to kill an escaped ramflero? Did he knife the man in the neck on a busy street in front of a casino and escape before the police helicopter arrived? Does it matter whether this boy did this thing in this place? Or whether he and his homeboys spun it out of a collage of their experiences, Hollywood films, and the internal stories circulating and transforming endlessly in the unstable myths of the MS?

Of course it matters. Let us assume, for a moment, that his story is true. That Andy did make this trip north, and his US compatriot parodied the film scene to the young missionero. The film itself is based loosely on the very real spaces, events, and even personalities that spawned the Mexican Mafia. It is also a “foundational text” of gang culture. Central American cliques connected to both MS and 18 present the film to new recruits to teach them the ethos, history, and meaning of the Latino gangs. It became the script through which Andy performed this murder. All of them—Andy, the US homeboy, and even El Smokey—became actors reinventing a piece of theater that itself is a simulacrum of real events. Art imitates life, life imitates art, in a chaotic circuit that never seems to end.36 And in telling the story to me, Andy spun the cycle onward, drawing me (and through me, you) into a performance of violence that is not locked in time and place, but is staged again and again before new audiences while drawing on a Hollywood invention that has now become an intimate element of the real. Or he lied to me sitting in the prosecutor’s office. Why? Did he lie so that the poor chance at immortality I offered would be commensurate with his imagination? Because the invented story shines so much more than the violent drudgery much of his life in actual fact was? Such glaring uncertainties are not separate from the violent acts they obfuscate, but in fact are integral to how this violence becomes woven into the world. That is, these fantasies and falsehoods are irrevocably linked to both the rationale for and consequences of acts of violence. Together, the act, the narration, and its reception tie the dead bodies to efforts to justify, mourn, or exalt the violence and enhance the sense of power that, no matter how fleeting, the story can provide the teller, who, no matter how he tells it, may or may not be the doer. Approaching the scene from the “outside,” one can watch the bloody drama and count the dead and sometimes identify the actors and even analyze their roles. But how is all this violence and suffering scripted, and to what end?

Ultimately, the meaning of this story goes deeper than whether Andy actually did this thing in this place the way he said he did. Andy, speaking to me, answering my questions, caught up in the maelstrom of his last days, explained his life to me this way, using these words and these symbols as anchors in the story. Storytelling always entails an act of self-creation. Whether the Las Vegas story was true, a flight of whimsy, or an allegory for something else too painful or too mundane to tell, it exposes a brief fragment of the self that Andy invented and reinvented to survive and, perhaps, to survive beyond his time and place among the living. In my effort to capture and convey his experience, I have become another purveyor of Andy’s life and death, adding one more degree of separation and sowing one more set of sutures to keep the whole thing from coming apart at the seams. Still, I cannot stop the narrative from unraveling. Every facet of Andy’s life, every version of his life story that he told and that I inferred, every lie, flight of fancy, and grim confession recede into the event horizon of his murder, from whence they cannot be reclaimed. That Thursday afternoon when another youth about his age blasted five bullets through his skull forms both the beginning and the end of Andy’s story.

After killing El Smokey, Andy returned to Guatemala and was finally “jumped in” (brincado)—officially accepted into the gang. He was thirteen years old, a bona fide homie belonging to the MS’s bloodiest and most powerful clique in Guatemala. Three years later he helped organize the crime of the four heads. Shortly afterward he walked in on El Pensador, his ramflero, snorting cocaine, an act prohibited by MS internal rules (alcohol and marijuana are okay; anything else receives swift punishment). Andy reported his ramflero’s violation to the other homies, but El Pensador denied everything, threatening to turn Andy into ceviche. Andy knew well enough not to hang around after his ramflero made this kind of threat. He split with three other guys, Gorgojo and two other young chequeos dissatisfied with their indentured servitude, leaving CLS forever.

A year later, a dismembered female body in a trash bag appeared in front of Andy’s house in zone 5 of Guatemala City. His “marero-ness,” it seems, was obvious to his neighbors, and someone fingered him to the cops. He roundly denied his guilt—“How could I be so stupid as to leave a corpse in front of my own house?”—but no one listened. Fearing the real possibility of going to adult prison and seeing an opportunity to get back at the MS, Andy told the police he could give them the perpetrators of the quadruple decapitation. In exchange, they promised to make him a protected witness.

Three months later, under armed escort on his way to give testimony in the Tower of Tribunals, Andy said, he caught sight of a CLS member waiting outside the underground entry, watching the media and prosecutors streaming in. His collar was pulled up high to cover the tattoos on his neck. They locked eyes for a second, Andy said, and that’s when he knew. He walked on through the warren of tunnels beneath the Supreme Court, into the cramped, stuffy courtroom. Sitting before the sweating judge, he put it all down on tape, all he knew of the MS: the leaders, the structures of command, the weapons caches, the fronts, the accountants, the soldiers. Extortion networks. Murdered children. Bodies buried in basements.

Andy’s story is a collection of memories twisted by trauma, fantasies of power, and Hollywood invention, lies and myths that he drew upon in his narration of his life. This layering of truth and fantasy was by no means his alone. Storytelling is always an exchange between the actor and his or her audience. This exchange takes place as much through the fantasies we project upon one another as it does through the truths we believe we are sharing. As Andy engaged with his violent past and impossible future, he fulfilled law enforcement officials’ fantasies of protecting society from gang atrocities. And through our brief encounter, he fulfilled my own dream of delving into the life of a “real” marero. His violent death permanently blocked the possibility of continuing this exchange, providing an abruptly certain sense of closure to a narrative filled with lacunae and ellipses. And now, the only way I know to give back what is owed is to keep the promise I made to Andy of a poor kind of immortality. I have constructed a hall of mirrors out of the shards of Andy’s life to reflect how acts of brutality are etched into life through the endless blurring of truth and fantasy, memory and myth. And though Andy’s story may appear singular, it is not. As I explore in the next chapters, the processes of violent creation and destruction that shaped his life, his death, and his story are in fact layered into the making of the maras, and of the world itself, on a far grander scale.