Читать книгу Mortal Doubt - Anthony W. Fontes - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBrother’s Bones

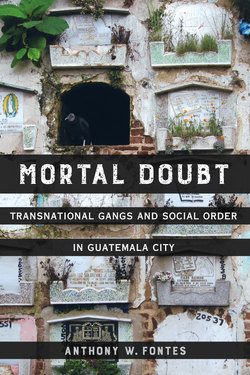

FIGURE 10. Sepulchers in the Guatemala City General Cemetery.

Calavera and I climb a ragged stone staircase up a low rise in the middle of the cemetery. He talks of how he wishes he could forget much of his past, but also how so many memories slip away no matter how hard he fights to hold them close. In prison, it was easier to simply not think of the dead or of problems beyond his capacity to solve. Having witnessed so many men lose themselves raging against their past and the present it had made, he became adept at forgetting. But since walking free, his past has mounted a clandestine assault. Ghosts mark him from the shadows, from just around a corner, and in strangers’ sidelong glances. They are whispered reminders of all he survived and the unlucky bastards who did not. The cemetery is rife with these ghosts and their stories. Some of their stories he lived, too. Some he heard from his sister, Casper, and others, repeated so many times they became his own, slipping into his dreams.

One such story begins with his brother Giovanni walking through the old neighborhood more than a decade before. Where the path forked a young man sat on a broken cement bench, staring at his hands. It was Casper. When he saw Giovanni, he straightened up, calling out, “What do you think they have waiting for us, carnal?”

“El Soldado said it was to make peace with the Boyz 13.”

Casper spit. “Those motherfuckers. I’d sooner skin my dick.”

“Well, we’ll find out,” Giovanni shrugged. “I’m just glad you came.”

“Of course I came,” Casper blurted, then caught himself. “Where the fuck could I run?”

Giovanni looked at Casper and then beyond him into the ravine of trash and the slums clustered against the steep hills on the other side.

“Come on,” he said. “It’s time.” The left fork cut between two weather-beaten and crudely graffitied tin warehouses, then made a precipitous drop to a packed gravel road worn by dump truck tread and the soles of trash pickers. Giovanni started down the right fork that twisted across a desolate space pocked with crabgrass, broken bits of masonry, and scrap metal. Casper followed. More and more debris appeared as the path wound on, as if they were approaching the foundation of some blasted edifice, until it swung up sharply and into the cemetery’s outer border.

After a minute a plateau of broken and eviscerated crypts came into view to the left down the slope. They could see a cluster of dark figures gathered there among the ruins, some sitting, others leaning against scattered gravestones.

“Wait up a moment,” Casper said.

“What is there to wait for?”

“Just hold on, will you.”

“OK.”

They huddled against a mossy concrete slab. The sun had dropped into the hills cresting above the ravine of trash, swinging beams of light upward through the warship clouds strung in ragged columns across the sky. Suddenly the clustered figures threw their heads back and a shout of laughter echoed faintly, and Casper and Giovanni could hear traces of a deep voice speaking in rapid cadence. Then the men all rose, throwing up their hands in a salute, fingers cocked like claws over their heads.

“Vivo te quiero,” Giovanni murmured under his breath. “Look alive.” Then he stepped out onto an uneven dirt path. Muttering a prayer and crossing himself, Casper hurried to catch up. As they crossed the barren decline, the voice ceased and the figures turned together, marking their approach.

The one who had been speaking was El Soldado. He stood apart from the others, shaved head shining in the fading light.

“You are here,” he said.

Giovanni shrugged. “I told you.”

“Why did the others run?”

“They do not want to kill their neighbors. We’ve known those boys since we were kids.”

“They would kill you if it suited them.”

“Perhaps.”

“Órale,” Soldado said, signaling to the other homies. Several ducked behind a concrete mausoleum and emerged dragging three figures, wrists and ankles bound with wire. They were so bloodied and beaten it took Giovanni a moment to recognize them. They were all that remained of the Boyz 13.

As Calavera tells the story of the Boyz 13, we stand atop the low rise amid mausoleums marked with Mandarin characters, looking out onto the cemetery. Below us, long corridors of the dead cut through dense stands of broken pillars and concrete crucifixes. The cemetery ends abruptly above the ravine.

In this telling, Calavera has put himself in Giovanni’s place, making his brother’s story his own. He points toward a plateau at the cemetery’s edge, hazy in the distance. “It was right over there, on that patch of grass just before the garbage dump. El Soldado called the two of us over, Casper and I, while the others kept watch on the Boyz 13. El Soldado had this terrible smile on his face. ‘Look here,’ he said in a low voice. ‘Right now you have a choice to make. Put an end to this charade once and for all, or . . .’ He nodded at the boys, all bloody and tied up, and said, ‘This has gone on long enough.’”

“Wait, who were the Boyz 13?” I ask.

“They were another clique belonging to the Letters like us, and they had gotten deep into drug trafficking, but for a dude named El Marino. El Marino controlled Barrio Gallito, over there, on the other side of the cemetery. We fought with them for years over drug puntos.” Calavera pauses, looking out over the ravine. “So I say, ‘’Right on then,’ and ba ba ba! Pistols for the two of us. Just revolvers, 38s. ‘Vivo te quiero,’ El Soldado told us. ‘Blast ’em, because if not I’ll be right here behind you and you too will stay here.’ Then he turned back to the other homies and told them to free the Boyz 13, that they could go.

“‘Your mother,’ I thought. And so the meeting ended and the locos started to leave. I don’t know what they thought was going down. They were just walking back along the way we had come. And we’re walking after them, and El Shark and El Soldado are walking behind us. And I’m like that, almost trembling with that feeling.

“And when those locos turn back and look at us, one asks, ‘What’s up dude?’

“‘Nothing.’ I said. Then I started firing. One of them fell, I made one fall. And then Casper started firing, and he put down another. But one of them got away.”

“Up that path there?” I say, pointing to a footpath leading back toward a cluster of rundown warehouses.

“Yeah, up that way, but it was higher then, less eroded. I could hear the sirens, the police already coming and I knew I had to get out of here, so I ran toward 26th and jumped the cemetery wall and from there to my house. But with the idea that one of them was still alive. ‘Sonofabitch, what a shitshow,’ I thought. They’re going to come for us. But it wasn’t so. The last one had three bullets in his stomach, and he died. He couldn’t take it. Ah.”

Several seconds pass in silence broken only by the sound of my scribbling in my notebook.

“I should have recognized then that it was all bullshit,” Calavera continues with a sigh. “That all the talk of blood brotherhood and loyalty and giving your life for the Barrio was just a charade. Soldado and the others were just trying to get El Marino’s influence out of zone 3 so they could control the drug houses. That’s it. So they made us kill each other like dogs.” He shakes his head, grimacing. “I’m just glad it wasn’t me who took three bullets in the stomach.”

We descend the stairs and turn onto a narrow path twisting between modest family plots overrun with creeping vines. Degraded by time, wind, and rain, many resemble ancient midden mounds. We turn a corner and nearly overtake a man dressed in ragged clothing bent over the pitted stone, pushing an empty wooden wheelbarrow. A boy walks before him carrying a battered metal bucket in each hand. The path is too narrow for Calavera and I to pass, so we slow and fall in line behind the two laborers. The old man smells of sweat and earth. A long knife in a cracked leather sheath hangs from a belt around his waist, softly slapping against his thigh with each step. Both man and boy are covered in a chalky dust from attending to the resting places of the dead. It is they who excavate the paupers’ graves, ferry the bones and tattered funereal finery, and fling them down the hole, human dust floating in a final wake.

We turn down another long corridor, and then another. Calavera knows, or thinks he recognizes, several of the dead we pass. He points a few out to me.

“These are the vatos who weren’t lucky enough to get arrested.” He laughs ruefully. He tells me how the police nabbed him at a checkpoint as he was moving crack across the city. Casper was the leader of Los Northside by then and promised to care for Calavera’s family. But the stipend Casper pledged never materialized, and Sandra was left to fend for herself and her daughters. Casper started going crazy, killing anyone who stood in his way. And he didn’t care when little kids or pregnant mothers got caught in the crossfire. Calavera read the newspapers, and his sister told him what was going down. He tried to talk sense to some of his old homies, but they were all scared of Casper.

“The way I saw it, killing women and kids was bad for business, bad for our reputation.” He shakes his head, “Don’t we all have brothers and sisters and children we want to protect? But Northside’s territory grew, and you can be sure that the Big Homies who were still around didn’t give a shit. And no one else either. There was plenty of newspaper reporting, but no one did anything.”

We reach a break in the wall, where Calavera signals for me to follow him to the right. The man and the boy walk on toward a water tower rising above the grounds. The boy joins a line of others stooping to dip their buckets in a well of murky water and draw them out again.

We enter a forest of concrete crucifixes, some broken and bent at rakish angles. Calavera halts suddenly, looking first one way and then the other.

“What’s wrong?” I ask.

He shakes his head and resumes walking slowly down a path that carves a slight descent to where the cemetery ends above the garbage dump. We reach the edge of the precipice. Motley debris is tangled in the vines and brambles carpeting the slope. Twisted rebar and concrete, battered coffins with bits of gray crinoline spilling out. A plastic baby doll sits upright among shards of shattered crockery as if a child’s tea party has gone awry. A greasy, cloying stench fills my nostrils. It is the smell of vultures. They perch on the limbs of trees and on every crucifix above every grave, black wings spread wide to dry in the sun, gray heads cocked to inspect newcomers. I inch out to stand on the exposed foundation of an abandoned mausoleum jutting out above the ravine. Below, diesel trucks rumble over the packed refuse, delivering the garbage of the heaving metropolis. Trash pickers move across the waste, tiny figures stooping and rising beside pools of metallic green water leaching through the dump and into a black river coursing into the bowels of the city.

I back away from the edge and follow Calavera along a sepulcher wall facing out over the precipice.

“He’s here, I know he’s here,” Calavera mutters to himself. “He should be here.” Again he halts and stands for some time facing the wall, closely inspecting each plaque. A name, a simple prayer, a life reduced to a hyphen. This one is faded by the elements. This one is favored with a flowering succulent. This one is carved in flowing font. A few plots have been bricked up and plastered over. One remains open, a blank blackness occupied by a vulture, head cocked, inspecting us with a single beady eye.

FIGURE 11. Tenements for the dead, Guatemala City General Cemetery.

“I must have it wrong,” Calavera says. “Let’s go to the next one.” The path ahead ends abruptly where the cliff has crumbled away into the ravine. We backtrack and turn down another corridor, surprising an adolescent couple necking, the boy pressed up against the girl against the wall. She giggles. The boy looks up, then nuzzles in closer. They cling to each other, ignoring my awkward greeting. Vultures perch atop the walls on either side like sentries, wings rustling and talons scraping against the plaster.

For the next hour, as the sun sinks in the west, we wander like that, crisscrossing the northwest section of the cemetery, vainly searching for Giovanni’s plot among the tens of thousands interred and innumerable missing. After a while, Calavera stops pointing out people he knows and trudges along in silence.

Finally, we stand side by side above the path leading to the old meeting place at the furthest corner of the cemetery.

“It’s confusing here,” I say. “And it’s been . . . well, it’s been a long time.”

Calavera just shakes his head.

“I’m sure your sister wouldn’t have let anything, uh, happen.”

“No.”

I fiddle with the recorder and jot a few words in my journal: “Forgotten? Discarded? Dead or not?”

Calavera pauses, and then, suddenly resolute, turns to head down the path to the old meeting place. “Let’s go, Anthony. Let’s see what’s down there now.”

A flock of vultures has gathered around a corpse of one of their own stretched out like a patient etherized upon a table beside a pillaged grave. They flap away lugubriously as we approach, dispersing among the scattered trash and headstones worn indecipherable in the undergrowth. Calavera pokes around, looking for his name and others he and his old compatriots graffitied long ago. I walk the perimeter and stop suddenly before a ruined mausoleum.

“Oh shit,” I say, and call out to Calavera. “Look here.”

Calavera joins me. The mausoleum wall has been graffitied in black spray paint. An M and an S, a 13, and a cartoon crown and skyscrapers. A date is scrawled beneath: 21 May 2012. That is two days ago.

We both turn to look out from the plateau toward the footpath leading back to Calavera’s neighborhood. After a few moments, I say in a low voice, “Perhaps we should be leaving.”

Calavera’s gaze lingers on the graffiti. “Yeah, OK.” He shakes his head. “What a shitty tag. I tell you, kids these days don’t know shit.”

As Calavera walks with me away from the meeting place at the edge of the cemetery, one more memory rises up unbidden. It was the last time he saw his brother. Giovanni was driving a Honda civic with tinted windows on the outskirts of Xela. The air coming through the windows was hot and dry. Casper—already ramflero of Salvatrucha Locos de Northside—sat in the front passenger seat. Giovanni had invited him against Sandra’s wishes. Sandra was in the back with her infant daughter suckling at her breast, sitting next to Calavera. Calavera watched the baby breastfeed while pretending to look out the window: her lips straining at the nipple, her eyelids squeezed shut as if the light flitting through the car were blinding. Sandra was listening distractedly to Giovanni and Casper talking, when Casper suddenly turned around and fixed Calavera with a grin.

“One more to feed the nation, huh,” he said, turning back to Giovanni.

Giovanni looked over sharply at Casper. “What did you say?”

“I said, one more little vato to make the mara strong.”

Giovanni jerked the car to the side of the road and skidded to a stop in the gravel. “Listen, dickhead,” he said in a quiet, charged voice, “my brother will never join the gang. I do not want this life for him. He is better than this. Do you understand?”

“Calm down, brother. I was just . . .”

“I said, do you fucking understand?”

“Yeah yeah, of course. Don’t worry man. I was just joking around. Why don’t you smoke your joint and chill out, hey?”

Still glaring at Casper, Giovanni shoved the car into gear and pealed out onto the road. Sandra and Calavera exchanged a startled look, both too afraid to speak. Casper stared stolidly out the window at warehouses of sheet metal, unpainted, boxy things where men covered in grease moved like ants among the carcasses of dead tractors, semis, and other machines strewn about the gravel lot.

FIGURE 12. Mara Salvatrucha graffiti on gravestone, Guatemala City General Cemetery.

As they drove, Calavera watched his brother’s face in the rearview mirror, the tattoo tears etched at his right eye, the gothic script down his neck. In those days he was always angry about one thing or another, stuff he never discussed with Calavera, or with any of his family, if what Sandra said was true. As Calavera watched, Giovanni looked up into the mirror and for an instant they were caught in each other’s reflected gaze. What Calavera saw there he was never able to name: an infinite sadness, a secret window into his brother that he’d never seen before and never would again. Perhaps it was all the hopes and fears that would break Giovanni to pieces if he let them loose. Calavera wanted to wrap his arms around his brother’s neck and cry. Then Giovanni turned his eyes back to the road. For a long while, no one spoke.