Читать книгу When Quitting Is Not An Option - Arvid Loewen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4. Between the Posts: Canada, Part 2

By the time I got my cast off in January, I had made enough of a connection with a few guys from my school to know that they were playing soccer. One Sunday evening there was a practice at the high school that backed onto our junior high school (they shared fields), and I decided to go to the practice as a spectator.

The gym was full of boys my age and older. They were quick and strong, and I watched tentatively from the side. I was wearing my runners, just in case. The balls bounced off the floors, the gym walls and occasionally the roof. I was itching to get out there and race around, to feel the ball make contact with my feet, to catch it between my hands and roll out of a dive. I looked down at my leg, thankful that the cast wasn’t there anymore.

A few of the players were talking and looking in my direction. After a few drills it looked like they were starting a scrimmage, and I started inching my way closer. The coach looked my way and waved me forward.

“You want to play?” he asked. I nodded, too afraid to say anything. “Okay,” he said. “We’re making teams.” He looked down at my legs. My left leg was significantly smaller than my right, the muscles having atrophied from lack of activity while they had spent the last three months cooped up in a cast, forced to swing like a giant club foot attached to my leg.

“I broke it a few months back,” I explained.

“It’s good to go, though?” the coach asked. I nodded.

“All right.” He clapped his hands on the ball and blew the whistle. The players gathered around, and some laughs were exchanged, though thankfully not at my expense. They were friends and had clearly known each other for a long time. A few balls were bounced, and one of the players tested a few of them out with his feet before deciding on the game ball.

Players were spreading out as the coach put them on their teams. I went back to the side where I’d been standing, making sure to hide my limp as I walked. I’d been chosen as a goalie because I didn’t have great mobility with my weaker leg, but I still wanted to keep my weakness hidden as much as possible. With a blow of the whistle the ball was thrown into play and the game was on.

Adrenaline surged through me. I had played back in our cow pasture with the natives. I had played on my own behind the barn, kicking the ball off its uneven surface for me to catch.

But this—this was a game.

The ball was bouncing lightly on the ground, kicked back and forth by the quick feet of the boys. I watched it with sharp eyes, observing which players I had to make sure to keep an eye on. A burst of speed here, a quick dribble and deke there. Soccer had always been my love, and it was quickly becoming my passion.

The opposing player was coming up the left side with a good lead on my defender. The striker shifted the ball from the left to right foot effortlessly, and my eyes caught a blur of motion out of my peripheral. His body language made it look like he was going to kick, but there was something in me that knew he wasn’t.

I jumped into action, springing forward. The ball came off his foot with a sharp curl, two feet off the ground. It was going directly to the opposing striker, but I had guessed correctly. With a quick slide on the ground, right up to the edge of my crease, I had the ball in my hands. I was back on my feet in seconds, scanning the gym and spotting an open midfielder moving up the gym. The ball was at his feet in seconds, and he was off.

Taking a deep breath, I realized I had made my first real save. And it felt good.

The coach was looking in my direction, and I absorbed his gaze without returning it.

Diving, catching, blocking, anticipating. It’s all a part of being a goalie. Within five minutes I had made good use of every part of my body. I could see in the coach’s eyes that he was impressed. I’d later find out that he’d been commenting on my performance. “Wow! This kid is fearless. He’s as quick as a cat,” he’d said. “There’s potential here.”

It doesn’t take news—good or bad—very long to travel around a junior high school. By the next morning my school life had changed. I had gone from being an immigrant to earning a level of respect because of my athletic ability. In many ways, soccer was what got me through the rough years as a teenager.

* * *

Soccer quickly became a huge part of my life. As soon as the coach saw my ability, quickness and agility, I was involved in a team. I joined the North Kildonan Cobras as a 14-year-old, and within a year I had been elevated to the highest level I could play. While still a juvenile I joined the senior league, including playing a season in the second-highest senior division. Beyond that I moved up to the Premiere division (the highest level of amateur soccer in Winnipeg) and played on the Manitoba all-star team from the second year I lived in Winnipeg until my soccer career ended.

I ended up playing in the Manitoba games and the Canada games, as well as being chosen by a few club teams to represent them when they went to their homeland for a tour against club or national teams. They wanted to keep themselves from getting embarrassed, so their own goalie sat on the bench, a scowl on his face. It allowed me to travel at no cost and play soccer at an elite level, which I thoroughly enjoyed.

* * *

The Bermudian sun had disappeared over the hills on the horizon. The game was in full swing, and we were down 2–1. We had travelled to their country to play their national team, but the grass underneath my feet felt the same as it always did—springy and forgiving, until I chose to dive.

The wind whistled through the net behind me, and the net began to move. I turned to look, taking my eyes off the play for a second. It wasn’t moving the way it normally would from the wind. There were points of the mesh that were being pulled back, hands hanging onto the net. There was chanting and yelling, the sound just in the background of a game that, though the score was against us, was going in our favour.

There was a yell from up the field, and I turned to look. One of our forwards was moving up the left side of the field, displaying his ball control as he took it inside against one of the defenders. Being in the net, it’s easy to see how the play is unfolding. Like the quarterback on a football team, soccer goalies can direct play and correct their players. They have a vantage point that no one else on the field does. But even if I had yelled, he wouldn’t have heard me—with almost no bleachers around the field, the fans were allowed within six feet of the boundary line. The lighting on the field was extremely direct and perfectly aimed, its limits dropping off as soon as you crossed the white line. Given that we were in Bermuda, the entire audience of somewhere near two thousand, circling the field and yelling behind me, were not the same skin colour as us and blended into the night perfectly. I shot a glance back at the crowd behind me, catching a glimpse of small glowing white sets of teeth in a sea of black.

Jimmy was streaking up the right side, in perfect position for a cross. Both teams had left their goalies out to dry numerous times, allowing for an open and fast-paced game where the ball spent more time moving up the field than hanging out in the middle. The cross came perfectly to Jimmy, and I saw him put on a burst of speed to pass the last defender, staying perfectly onside. The goalie was scrambling, but I knew how it felt to be in his situation. His momentum would carry him right across. To do anything less wouldn’t stop the play.

Jimmy played the ball perfectly, behind and underneath the goalie’s jump. It bounced once, curled onto the inside of the post, and was absorbed by the back of the net.

Our team began its cheer, running back to our own side. I pumped my fist in the air, smiling at the fans behind me. They may have been cheering against me, but they were great fans who appreciated sport. I’d already proven my merit against them by stopping some of their top players on fast breaks that should have ended in goals.

There were only a few minutes left, and Jimmy had just tied it up. It was a friendly game, and we determined our own format—neither team wanted to leave it to a tie, so the intensity picked up. Either a team would break the tie or we’d go to a shootout.

Another fast break. A tall forward was moving towards me up the left side. I positioned myself perfectly, anticipating where he would be moving. My defender became a pylon as the man’s quick feet brought him around to me. I could play the pass—I had seen the forward making his move—or I could take the shot. I saw his eyes, and my reactions saved me. In one split second I dove left, going for the shot. He’d aimed that way, and the ball went off my elbows and into the ground. I crumpled on top of it, tucking into a ball and not letting go.

The crowd’s yells surged out unbearably loud, but I could sense that there was more than disappointment. The Bermudan players were staring their own fans down, and words were being exchanged. It was friendly, but there was an edge. I started to get the feeling that the fans had given up on their team and were mocking them. They’d seen me react point-blank numerous times and knew that that meant one thing—if the Bermuda team didn’t win it now, they’d have no chance in a shootout.

Shrill and barely audible above the crowd, the whistle ended regulation. We were going to a shootout. The mocking intensified, the fans not helping their players out but just having a good time. As I came back towards the line in my net, the fans were whipping the back of the net into a frenzy. If the ball did go into the net, it would clobber them. I stepped on the line, flattening the grass and planting my feet.

In soccer a shootout highly favours the shooter. The goalie isn’t allowed to leave the line until the player has contacted the ball, so it’s purely a gamble. The ball is planted so close and the net so big that to even think that one can react in that much time is ridiculous. The goalie must anticipate, jump and hope. Goalies have to pick a side, and it’s not uncommon to see the goalie jumping through the air and the shot dribbling down into the middle of the net. If the player can trick the goalie, the net is his.

The first few shots were give-and-take, the teams even. Then we took the lead. Bermuda was shooting first on the fifth and final shot. We were up by one, which meant that if I made the save, the game was over.

Behind me, the net was an undulating sea of string. I couldn’t hear myself think over the sound of the yells, catcalls and screams. The fans were surging ever closer to the lines and net. I felt like they were breathing down my neck, yet I still couldn’t see anything other than their smiles and open mouths in the dark.

Their last shooter was one of their best. I’d stolen the ball from him on several occasions in the middle of the game. He met my gaze, then looked away. Some players look where they’re shooting. Others avoid where they’re shooting. Some try to play mental games; others just shoot. He didn’t give any indication—just planted his feet a few steps from the ball. I could feel my pulse in my ears, the crowd washing away to the background fuzz on a radio.

He stepped forward, beginning to run. His cleats dug into the ground, grass clumps flying behind him. I dug my own feet in, moving one step to the right and taking a leap—it was a complete gamble, a guessing game. I launched into the air, my body flat-out four feet off the ground. My hands stretched out. The ball was launching through the air, coming off his foot like a rocket. The crowd’s noise rose.

And my hands closed around the ball.

I hit the ground, rolling away with it between my hands. The crowd exploded—all kinds of noises, catcalls, jeers and mocking, aimed mostly at their own players instead of us. I’d earned their respect, and I was thankful we had made friends instead of enemies.

* * *

I played hard, tough and aggressive. But my reputation for having no enemies on the field, a seemingly contradictory puzzle, may have saved my skin during a rather tense game.

I was the South-American misfit on a Czechoslovakian-owned team named Tatra with Canadian-born and Scottish imports. During those years the ethnic presence was far greater than it is today. The level of rivalry was intense, especially given that this was Premiere soccer, not national matches. We were playing the Portuguese, a team that stayed very true to its ethnic boundaries. When two players of even skill were available, they would take the one who was Portuguese. Every time. Not only was the rivalry rather intense, but they happened to have very devoted fans. The games could get rough, especially a game as important as this one.

The field at Alexander Park was well-kept, the changing rooms on the far side from me. The bleachers were on both sides, wide banks that sat around two thousand. And today, about 5 percent of those fans were ours. The other 95 percent were for the Portuguese, and they liked to make it obvious.

The game had been close and intense. On the field, I could see everything that was happening. I never had my back to the play, so everything unfolded in front of me. Our forward was streaking up the right side, the ball on his feet like it had been glued there. He stopped on a dime, turning to cut inside. The defensive player got in his way, hacking at the ball. They ran into each other, the ball dribbling away from both of them. The whistle blew—a foul had been called. The Portuguese player, clearly not happy with what had just happened, spat at our player.

Our Scottish contingent, not being shy to express their opinion of things, retaliated. With a head-butt filled with anger our player knocked the Portuguese player onto his backside. Immediately there was an uproar. The crowd surged with anger and—if they had seen the spitting incident they clearly didn’t care—began to reach a boiling point. Our players were getting tangled up with theirs, faces red and veins protruding from necks as everyone was yelling. There was clearly a fight beginning on the field, and there was nothing stopping the two thousand Portuguese from storming the field—and storm they did. Like a tidal wave crashing onto shore they hit the grass, anger written all over their faces in plain Portuguese.

The odds for our team had majorly shifted, and my players realized it. With the realization that the game was over, they sprinted for the change rooms. The Portuguese were still yelling, tempers at a rolling boil. The crowd had reached the field now, yelling with their fists in the air. My team made it to the changing room, locking themselves in. They were safe.

I was still on the far side of the field. There was a fence behind me, and bailing over it was an option. I stood in my penalty box, asking myself, What the heck am I supposed to do? The crowd was livid, the game definitely over. And I was all alone, a South-American misfit representing a Scottish contingent that had ticked off two thousand Portuguese. Things weren’t looking good for me.

The crowd wasn’t getting any calmer, so I decided that I’d better make my move sooner rather than later. Besides, I didn’t want to sit out on the field for an hour and wait for them to notice that I was there. I left my penalty box—my little island of safety—and walked towards the mob. Still yelling, still angry. When I got within a dozen feet, those nearest me noticed me there. I kept walking—directly at them.

They parted like the Red Sea, and I walked right through. I felt a little like Jesus in Luke 4, a story that suddenly became abundantly real to me. When I walked, they moved to make space for me. People reached out to touch me but not out of anger. I got pats on the back, cheers, high-fives.

“Good game,” one said.

“Well played,” another added.

“Thanks for being a great player.”

“That was a great save!”

“Way to go!”

I walked out the other side, unscathed and completely in one piece. My reputation had preceded me—literally—and I was able to walk through an angry mob of very charged fans.

My team opened the door to the change room when I told them who it was, and I got a chance to see the surprise on their faces before the door slammed shut behind me, the lock clicking into place. Outside, the anger had come to the surface once more, and the Portuguese began banging on the side of the trailer, throwing rocks onto the top and at the sides.

We were hushed in silence, though our atmosphere was anything but silent, for about an hour, until the police finally arrived to escort us from the scene. Making friends instead of enemies had paid off for me—in a big way.

* * *

Dad, when he was a teenager, had swum across one of the major rivers in Russia and almost drowned. Though it wouldn’t have served any practical type of purpose, he understood, just like many athletes do, the drive to achieve and accomplish. If he had grown up in other circumstances, where he could run for fun instead of to save his life, he would have understood better the intensity with which I approached soccer and sport.

On the other hand, Mom didn’t understand my drive one bit. She had always had the idea that a human heart was only given a certain amount of beats to take it from birth to death. If you raised your heart rate, you were shortening your life. In other words, why do something that required energy if you didn’t need to? If the life you had (like we had found in Canada) could allow you to sit on the couch when you weren’t working, then why would you be running around a grass field chasing a ball?

They had no idea what I had gotten myself into or, especially, at just what level I was playing soccer. After I convinced them to come to one game (and they came to only one), Mom had a few comments. Looking a little concerned, she met me after I came out of the change room.

“Arvid, how come they didn’t give you the ball very often? That was not very nice of them.

“And when they gave it to you they would kick it so hard it was difficult for you to even get it!

“Then again, it was nice of them to have that mesh behind you so when you missed the ball you didn’t have to run far to get it.

“And by the way…” She was being motherly now, telling me just how to behave. “You should play nicer. Stop taking the ball away from other people.”

* * *

I was on the cusp of moving up in the soccer world.

“Loewen brilliant in defeat,” the headlines read.

We had played a team called Hibernia, a team from the Premiere league in Scotland. The game was in front of 6,000 fans, and we got our egos handed to us on a platter, losing 6–0. But the score didn’t adequately reflect just how one-sided the game had been. The attacks were hitting me like rain, coming down one after the other. It was like playing pinball—I would boot it down the field and away, only to have gravity suck it towards me again, another attack inevitable. I played well, taking the ball off some of the forwards with my agility and reflexes. Their team had huge guys, and I made a save when one of their biggest had an open net from the penalty spot. Diving completely sideways, lying flat-out, I took the ball straight in the gut. He left the box shaking his head in disbelief. I had been following these guys and their careers and was elated to be able to hold my own. After the game, the coach of the Hibernia team was quoted as saying, “He’s agile with good reflexes and a quick mind.”

That same team extended an offer for me to get into the development league for them. It was my chance to go pro, and I was being seriously considered. While the idea of playing soccer professionally was certainly tempting, there were other factors to consider. Injuries are a big part of any sport, and I was no different. Standing in front of a soccer ball travelling at high speeds, as well as players pummelling towards me, meant I got hit or hit the ground quite often. My fearless style of playing had led to a few concussions by this point, and with one concussion the next comes far more easily. Injuries were one factor; size was another. I had never been a big guy. For the majority of my amateur career I could get away with being small—my quick speed and anticipation, for which I was well-known, helped me out in that regard. But the higher you go in any sport, the more all the other players have those attributes as well—and size. Being only 5'8", it was a tough field to crack.

In addition to Hibernia, I went down to the States for an open-trial camp for the newly developed indoor pro league. Because I was an international player, they told me it would be tough—they only had so many international slots available on the roster. Instead, they recommended I go to the New York Cosmos, then the home of Brazilian soccer legend Pele. But I didn’t go.

If injuries and size were factors, there was one other significant factor. My faith had been growing over the years, and in the context of amateur leagues it was not a difficult thing to do (though being an elite athlete in a competitive environment at the same time as being a Christian is not an easy thing). But moving up to the professional level would bring with it all kinds of lifestyle temptations that I wasn’t willing to bend on. That, and the fact that back at home there was a special girl who was starting to become a bigger and bigger part of my life. If I wanted to spend more and more time with her and invest in our future as a couple (and hopefully a family), being across the ocean would not be beneficial. And so I decided that it was time to make a change and to consider the long-term future.

I would stay in Winnipeg.

If soccer wasn’t going to be my career, something else would have to be. After graduating from high school in 1975, I went to the University of Manitoba. I enrolled in the education program. I figured if I liked sports so much, I may as well do them for the rest of my life and get paid for it—so I wanted to be a gym teacher. There was also a good incentive: joining the U of M soccer team. The season started before the fall semester began, and I loved playing. It ran into the autumn, and I could barely think of anything else.

* * *

Shortly after classes began, I realized that I loved sports but had no interest in teaching sports. I only wanted to participate. Most of the classes were bearable, but there was one that I just couldn’t take. The minute I walked into the classroom I knew I was out of my element. There were mats on the floor, with some soft music playing in the background. I felt more uncomfortable than if I’d shown up on the soccer field naked. The teacher was wearing some extremely tight shorts and shirt, and I had to look away from him. Some of the students filing in were averting their eyes as well. The class was called “Movement Education,” and it was about to make me throw up. There was a sign-in attendance sheet, and I scribbled my name as if I was being treasonous and wanted to get out as fast as possible.

When the teacher started talking about the fact that we were going to be teaching kids how to move to music, I almost threw up my lunch. The last time I had danced was—never mind, I think I erased that memory from my mind. There was no way I was dancing in front of a group of adults, never mind teaching kids to dance. This isn’t gym! I wanted to scream. And then the teacher dropped the biggest bombshell of them all.

When he moved to the front of the class, leaning over to stretch his body in his bright leotards, I tried to hide behind the other students so he wouldn’t even know I was there. It wasn’t easy, as everyone kept bouncing around like the floor was on fire.

“Class,” he started, “welcome to Movement Education. As we’ll be dancing and stretching in this class, it is strongly encouraged that you buy some spandex or Lycra to feel comfortable.”

Comfortable? I thought, Who can possibly feel comfortable in clothes like that?

While the rest of the class snickered or nodded, I snuck out the back door and didn’t come back. There was no chance I was going to be in that class. As I walked away, I distinctly remember thinking, Like I’m ever going to be seen in spandex!

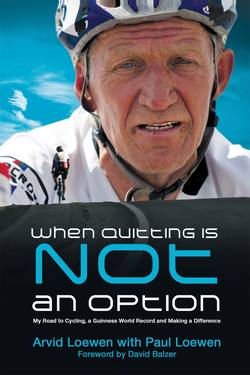

“If you can touch it, you can catch it”

Fearless in pursuit of the ball

Newspaper article highlighting Arvid’s game against Hibernia