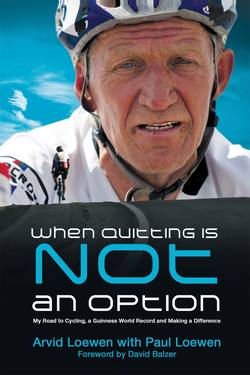

Читать книгу When Quitting Is Not An Option - Arvid Loewen - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1. The End: RAAM 2008

Click.Click. Click.

Click. Click.Click.Click.Click.Click. Click.

Click.Click.ClicClicClicCliCliClClClCCC.

The ticking of my wheels picked up speed as I crested the slight hill and started moving downwards again. Behind me, I could hear the revving of the support crew vehicle taper off as they, too, coasted with a bit more speed. That slight uphill was nothing compared to what I had already experienced in the first five days of the ride.

Five days? I asked myself. Has it really been that long?

Is that all it’s been?

* * *

“Hey, Arvid!” Ruth called out of the side of the van, pulling up beside me. “Up ahead is the McDonald’s they were telling us about. Free food for all Race Across America riders and crew.”

Biking 20 out of every 24 hours takes a toll on the body, and there’s almost no way you can replenish the energy you’re expending. With that much output, you’re forced to take in as many calories as possible—through whatever means possible. Milkshakes and Big Macs had become some of my favourite. This would be a great place to load up. I needed somewhere between 8,000 to 9,000 calories in 24 hours. If you’ve ever tried to eat that much, you’ll realize it’s more or less impossible. Which is why I was losing weight. It was day five, and I’d already dropped a few pounds. By the end of the ride I would be down 5 to 10 lbs from my starting weight. A quick weight-loss program if I’ve ever heard of one.

“Sounds good,” I said. “We’ll stop there, and I’ll take a short break. Can’t waste time,” I added as they drove ahead to the golden arches in the distance. I was alone in my thoughts again, with only the sounds of my bike ticking and the hum of the tires on the road.

Ultra-marathon cycling is a solitary sport, one that puts you against the road. There are other competitors out there, but the battle comes down to you versus you. In the end, if you lose, it’s you defeating yourself.

I snapped my head up just in time to turn into the parking lot, taking my foot out of the right pedal and coasting to a stop. Josh was there to grab the bike from me as I lifted my foot over the frame. I shook my head, trying to clear a slight pain that seemed to have settled in at the back of my neck.

“Do you want a Big Mac, Dad?” my daughter, Stephanie, asked. “Vanilla milkshake?”

“And a Coke,” I nodded, my throat a little hoarse. I couldn’t tell whether the headache was from a lack of sleep or something more serious, but the caffeine couldn’t hurt. By this point in the ride I needed every pick-me-up that I could get.

“Rider 132.” Someone was coming my way, looking at his clipboard. “Arvid Loewen?”

“That’s me,” I responded, taking a sip from the bottle and stripping the gloves off my hands. Over time it seemed like they fused to the skin, the sweat bonding them together.

“So you’re a solo rider?” He put the clipboard on the ground and lifted a camera to his shoulder, adjusting the lens.

“That’s right,” I answered. “Solo. All 3,000 miles from coast to coast.”

“How are you feeling today?”

“Tired,” I responded, laughing out loud. “Not sure what else to expect.” I stretched my leg out, feeling the tightness in my hip. People always asked how I could possibly sit on a bike seat for 20 hours a day. I usually told them that by the time you stayed on a bike that long there were far more significant things to worry about. The pain in your butt was only the beginning of your problems.

“You’re nearly halfway there,” the man said. I wasn’t sure whether it was a comment or a question. Halfway, I thought, halfway would be nice. It’s all downhill on the other side, isn’t it? It’s a little ridiculous to think that biking five days continuously would only get you almost halfway, but traversing the entire continent in less time than many people drive it is no small accomplishment.

“Nearly halfway,” I admitted. I didn’t like thinking about it, though. I was stuck in the middle of the ride, and there was a lot of ground yet to cover. Those on the outside seemed to think that, somehow, past the halfway point it was bound to get easier. With ultra-marathon cycling, with anything ultra-marathon, the biggest challenge is always yet to come. The ride’s not done until you cross the finish line, and not a millimetre sooner. I was a lot more than a millimetre from the finish line.

“How has your ride been going?” he asked. I didn’t answer immediately. How can you sum up five days of intense heat (the Mojave Desert), oxygen-thin elevations (the Rocky Mountains), torturous mental exertion (sleeping less than two hours a night), mind-numbing terrain (the flats of the prairies) and more challenges than you’ve ever experienced in your life? To answer his question would have taken a few hours, but I didn’t have the time, because ultra-marathon cycling adds another mental component to the drama: everything, and I mean everything, is on the clock. Every pit stop, every fitful nap, every bathroom break, every second of every day is a part of your time. Already, sitting outside and waiting for my Big Mac was starting to feel like a waste of time, though my legs appreciated the break.

“It’s been going well,” I said. “As well as I could have hoped.”

“What do you think are your chances of finishing?” He moved his eye out from behind the viewfinder, as though he wanted to see, without looking through a lens, what I was about to say. He wanted to catch my reaction.

Stephanie reappeared with my Big Mac, and I took a moment to set it down on the table beside me, then plunked down and got ready to eat. He was still looking at me, waiting for an answer. Finally I decided to give him one.

“Fifty-one percent,” I answered.

I wasn’t sure if I believed what I had just said. I was in a fog, mentally not even close to 100 percent, and the ride was taking its toll on my mind and my body. Though I am a prairie boy and the bore of the terrain didn’t bother me, five days of sitting on my bike was having an effect.

“Are you going to get anything, Josh?” Steph asked. Josh, her husband, was part of our crew.

“We’ve been in the vehicle for four—no five—days already,” he said. “I’ve had enough of fast food. I think I’ll just get a salad.” He still regrets not taking advantage of free McDonald’s food.

Only a few bites in, I was already almost done the burger. Grease is helpful—once your throat is raw, it coaxes the food down.

“Ruth, do you think you could pour the milkshake into a water bottle?” I asked her. “I’m going to head to the washroom.” I stood up from the table and went towards the restaurant. The air conditioning would be a good respite for just a minute. The large McDonald’s sign dominated my view for a moment, and I saw what was written underneath: “Welcome Race Across America riders and crew!”

For 13 years, Race Across America (RAAM) had stood out in my mind as the pinnacle of ultra-marathon cycling. It was the Tour de France of the ultra world, though without all the doping and off-bike rest. No teams, no drafting, no sleep. And here I was, right in the middle of RAAM. For years I had secretly dreamed about it, told no one, and aimed for participating in the world’s toughest bike race.

And here I was.

As I stepped into the cold of the restaurant I shivered, not because of the temperature change but because of where I was. Because of what I was doing. A pain shot through my neck, and I clapped my hand to the back of it. There was nothing there. Nothing wrong with it. I took my helmet off—all of a sudden it felt really heavy.

I went to the washroom and questioned what I was feeling. Everything seemed to be normal. I looked at myself in the mirror. Since the beginning of the ride it looked like I had aged five years, if I was being generous. Maybe it was more like ten. My skin was hanging a little looser on my face, the wrinkles pronounced from the heat of the sun constantly beating down on it. My eyes were surrounded by bags, sleep deprivation taking effect.

I blinked my eyes and snapped out of it, then strapped my helmet back on. A little bit of pain wasn’t about to slow me down.

I walked back out, adjusting to the bright light of the day. Another rider had arrived in the time I was inside, and I tried to assess who was hurting more. Cyclists have a habit of looking at each other’s calves, thighs, butts and midsections. You can size each other up pretty quickly with a quick glance. But the farther you go in the ride, the less those matter and the more the face matters. You can train your body to cycle fast and hard, but eventually it becomes a mental exercise. Judging by his face and what I had just seen in the mirror, he was hurting even more than I was.

Ruth rolled the bike up to me, and I clambered on. “The milkshake is in the bottle,” she pointed, giving me a peck on the cheek. “Still 51 percent, eh?” she asked.

“That 1 percent makes all the difference.” I forced a smile, forgetting why, exactly, I was doing what I was doing.

Little did I know that percentage was about to drop—dramatically.

* * *

The sun was starting to set, disappearing behind the Kansas horizon. Fear climbed into my throat and lodged itself there. The nights are always the worst. It’s no wonder that people experience more depression when the days are shorter—the dark surrounds you and saps you of energy. But we didn’t get breaks and took them only when absolutely necessary, driven by the wobble of our tires as we struggled to keep our eyes open and our heads up.

My head dropped, but it wasn’t sleep that was the problem.

I pulled it back up, feeling some tension in the back of my neck.

Is my head getting heavier? I thought. But that was ridiculous. It couldn’t just get heavier. Then why is it so hard to hold up? There was only one answer to the question, but I wasn’t prepared to accept it.

I heard the surge of the van engine behind me, and it pulled even with me. “You okay?” Ruth leaned out the side window. My son, Paul, was driving, his wife, Jeanette, in the front seat. They had switched with Josh and Stephanie, who were sleeping in a hotel. In the morning Steph and Josh would have to drive to catch up.

“Why?” I asked, my voice hardly a croak.

“It looks like you’re falling asleep,” she responded. The crew, forced to drive directly behind me at night, had nothing to look at other than my slow, meticulous form in front of them. I should have known it wouldn’t be easy to get anything past them.

“It’s my neck,” I said, diagnosing the problem more accurately than a heavy head.

“Is it sore?” Ruth asked.

“Yes. But that’s not the problem. I can deal with pain. But it’s getting weak—I can’t hold my own head up.” The words sounded strange as they came out of my mouth. Holding up our own head isn’t something we usually worry about. It’s not something we even think about. But here I was, struggling to lift my own head because it weighed too much for my neck muscles.

“Can you hold it up?” Paul asked, leaning towards the window while still watching the road. “You know, rest it for a while?” I propped my elbow into the aero bar pads, then plopped my chin in my hand and let it rest. Awkward, yes. Functional, I suppose so.

“I don’t think much can make it better than taking a break,” I admitted. “I just can’t afford to stop.” The clock was ticking. Mercilessly. Relentlessly. I sat up straighter, thinking that if I kept my head in alignment with my spine instead of leaning forward and having to tip my head backwards to look at the road, it might be easier. But it still felt heavy.

“Let us know if it gets worse,” Ruth said, and the vehicle dropped back. According to the rules they could only drive beside me for a minute four times an hour. And I could never, ever, touch the vehicle.

Alone with my thoughts again, I fought the heaviness of my head. I tried shifting to different positions, but nothing seemed to work. No matter which way I sat, turned, twisted or stood, my head was simply too heavy for my neck. Though I was completely conscious and awake, it lolled down to my chest like someone asleep. If I hadn’t been questioning my finishing the ride, it would have been a comical situation. Unfortunately, when an integral part of your body starts to collapse on you, things don’t feel comical.

I propped my head up with my right hand. It worked, but the back of my neck still hurt. It forced me to constantly lean forward, an uncomfortable position for too long of a time. It also forced me to steer, shift and brake with only one hand. This put added strain on my other arm, as well as my wrist. After a few minutes I switched hands, fighting to get comfortable.

This continued for 24 hours. And it only got worse.

My wrists were swollen from the pressure of holding my head. The “rest” I was giving my neck wasn’t helping. If something didn’t change, my ride was over. Finished. Another Did Not Finish (DNF) in a career riddled with a mixture of successes and failures. I had come to the conclusion that my percentage had dropped from 51 to 10, maybe 5. There was no way I could ride this way for five more days—I had reached the end.

My RAAM was over.

Consuming milkshake before getting back on the road

Through the mountains and into the Prairies

Looking bored as neck problems begin to set in