Читать книгу When Quitting Is Not An Option - Arvid Loewen - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2. Determined to Succeed: Paraguay

We made our way through the trees in our bare feet, trying our best to be silent. Small steps and watchful eyes would hopefully keep us a few steps ahead of our quarry. The afternoon was bright and harsh—as always—and beat down on our bare backs. My older brother, Art, was holding the slingshot taut, aimed down at the ground. With only a split-second’s notice he could have it up and at the ready. Our prey was small but dangerous. Thankfully we could hear them far in advance.

The buzzing was obvious, and my brother signalled for me to stop with a slight movement of his hand. The signal would have been imperceptible to anyone else.

“Up there.” He flicked his head towards the tree straight in front of us. It was, maybe, 50 feet tall. My little eyes followed the trunk until what my ears heard matched what my eyes saw. A bees’ nest, some 40 feet up in the tree. It was a good 8 inches in diameter and 15 inches long—we had definitely found the sweet jackpot.

“You have a shot?” I asked. He responded by nodding. We didn’t quite speak, didn’t quite whisper. The sound was somewhere between the two, and it blended in with the sounds around us. The last thing we wanted was for our attack on the hive to be spoiled, sending us careening through the trees with nothing to show for it.

“I’ve got a shot,” he said, lifting his arms up into the air. Being older and stronger (for a while, anyway), he always took the shot. With his arms held high in the air, the slingshot cocked and ready to fly, he whispered out of the side of his mouth, not moving his head or letting his eyes leave the target.

“Remember,” he said, “when it comes down, you get it. If they attack, run—but don’t forget the hive.”

Right, I thought. Why am I always the runner? “Okay,” I whispered, sneaking closer to the tree. We were both about 15 feet from its trunk now, the sound of the hive buzzing in waves, rising and falling. He pulled the slingshot tighter, his aim true, and let the first clay bullet fly.

Thwack, it hit the hive. Instantly the buzzing increased in volume. The number of bees outside of the hive increased exponentially. There was a cloud of them now, attacking the tree angrily. Something had disturbed their home, and it was going to pay.

Without taking his eyes off of the hive, Art put another bullet into the slingshot and pulled it back. I held a two-foot club in my hand, spinning it lightly. It was the perfect size and weight, and its role was still to come.

He let loose the second bullet, and it missed the hive by an inch. Standing right beside him, I could trace its flight. The cloud of bees felt that they’d been grazed, and the intensity and volume of the buzzing increased.

Within a few seconds he had let a third bullet fly, and this one found its mark. Another tear appeared in the side of the hive. Like alarm bells had gone off in their home, the rest of the bees swarmed out to inspect what was going on and destroy the intruder. But they had no idea the intruder was far below them.

One more bullet to the hive should have done it—the bees were out of the hive now. The slingshot was the easy part. Art lowered it and hooked it onto his shorts, letting it hang and holding out his hand. I deposited the club into it like a relay baton. He swung it once, twice, testing its weight. Then, with the skill born out of practice, he cocked it back and let it fly. Now that the bees were out of the hive—supposedly—he would knock the hive off the branch, and it would fall to us. Empty of anything other than honey, it would land at our feet. The bees would be stuck upstairs, confused about why their house had just disappeared.

That was the plan, anyway.

His aim was true and the throw was strong—it knocked the hive off the branch. It careened its way towards us—though we still stayed a few feet back—bouncing off of branches until it hit the ground right in front of our feet. It had gaping holes from the bullets, where his shots had torn through it.

I went forward, diligent in doing my job. But something was wrong.

When I picked up the hive, I knew.

The sound of the bees had travelled to us as the hive came down. There were still bees in the hive.

“Run!” Art yelled, and I listened. But I didn’t forget what he’d said earlier—don’t forget the hive. I took off running in Art’s direction. Fear was written all over his eyes as he saw what was in my hand—and what was coming out of it.

Like Olympic sprinters out of the starting blocks we ran—not towards something but away from something. By now the cloud at the top of the tree had realized where their family and friends were and joined in the pursuit.

We hadn’t followed a specific trail, so it was a full-speed tilt through trees and bushes, the branches scraping at us while we dodged the trunks. I bounced off one, then another, clinging tight to the hive—a source of food for a family with little. We came out of the trees and into the open, our bare feet pumping up and down like pistons, our little legs a blur. Behind—and with—us came a horde of bees. Sting after sting after sting after sting. I was trying to swat them, but it didn’t work well with the hive in my hands and bees still pouring out of it.

Art was ahead of me, and we both knew where we were going. A large puddle—deep enough to swim in—was there for the cattle to drink from. Without hesitation we jumped headlong into the water, me still clutching the hive for all it was worth, and held our breath underwater. The bees couldn’t come down, but with the enveloping water and the still beneath the surface came the catch-up of the nerves—and the realization that my body was stinging like it was on fire. There wasn’t a part of me that didn’t feel like the bees were still leeching their poison into me.

I held my breath until I couldn’t anymore, hearing Art thrashing around beside me. I surfaced, only to spit my air out and grab another breath. At the same time I caught a glimpse of the sky around me—dotted with black and yellow bees like stars in the daytime. I didn’t need to be up longer than a second to realize they were still angry. Going back under I held my breath longer, my body fighting against the need to surface.

Several times later—finally—the bees had calmed down enough to leave. I left my head above the surface and waited for Art to come back up. Still stinging from the swarm we’d faced, his face broke into a smile the second he came up.

“You got it?” he asked.

I held up the hive, now soggy but still good, and smiled—13 bee stings were a small price to pay for our sweet loot.

* * *

When my forefathers arrived in Paraguay from Russia, they were given a tent, an ax, a spade, and an ox to share with another family. Given to my grandparents by MCC (Mennonite Central Committee), these tools made life possible, though certainly not simple. It was a meagre beginning, and it set the tone for the years that were to come, including my childhood.

Paraguay was never my family’s destination, fleeing from Russia due to religious persecution. Health concerns made Paraguay the only option available. They would take anybody that could breathe. Dad’s family had aimed for Canada but missed by a few thousand miles. Nevertheless, we were in a country that didn’t care what we worshipped or who we were, and it was now home.

With the tools they were given, my grandparents and their families set to becoming agricultural farmers. This included growing peanuts, cotton, and a small amount of grain. Agricultural farming is very dependent on the weather—particularly rain. The landscape of the Chaco (our territory in Paraguay) is mostly flat, like the prairies, with open fields and meadows. The natural grass (bitter grass that the cattle and horse can’t eat) grows three or four feet high, surrounded by bush. There are very few forests but a significant amount of dense bush. The roads were mud, subject to the dustiness of the dry winter season and the sogginess of the rain. Depending on their condition at the time of travel, they could make getting somewhere very difficult.

In winter the temperature dips colder but rarely below zero Celsius, the main difference being the lack of rain. Dust and sand whip up in columns and clouds, getting into every nook and cranny. The houses aren’t sealed, but the northerly winds would break any seal anyway, scattering the dust and sand in a layer that cakes just about everything. It provides a strange contrast, because the land is often green and yet suffers from significant drought. It’s this drought that has earned the Chaco the nickname “Green Hell,” a gritty yet accurate representation of some of the difficulties of the land.

With the dependency on the weather to co-operate, farming was not simple. Over time most farmers switched over to raising cattle. For my family this was on a very small scale with a small margin of success. The difficulty in growing up in this environment laid the groundwork for my understanding of what poverty is. We grew up without treats, with (hopefully) one pair of shoes at a time, and several instances when we were forced near to going hungry. I have a very vivid and clear recollection of the closest we ever came to not having food.

* * *

The strong northerly winds whipped into our home, and I coughed because of the dust. I had just come from outside, but it was too cold to remain out there for long. Though our house wasn’t insulated, at least it was a partial shelter from the wind. It was quiet in our house, which wasn’t uncommon, but something about it felt strange.

I went towards my parents’ room and was about to barge in when I fell silent. Thankfully my bare feet were quiet on the ground. I stood just out of sight, listening.

Mom was in the room, Dad, somewhere else. She was quiet, her voice hushed and quiet. When I listened closer, I realized what she was doing.

Praying.

Frozen in time, I wasn’t sure whether I should bolt and pretend I never heard or stand and listen. For better or worse, I chose to listen. The words were quiet and quick, and there was emotion laced in with them. Was she crying?

It must be something big, I thought. I couldn’t tell the words apart, and I didn’t want to be caught. At any moment a sibling could come walking by, and the game would be over—even though it had been accidental.

I heard the telltale sounds of Dad coming home and knew I had to move. Dancing away quietly, I stayed out of sight as he came into the house. He went straight to Mom, and I couldn’t help but creep closer.

“Did you get any?” she asked.

“No,” Dad responded. From my vantage point I could see him put his hands on her shoulders from behind. He stroked her arms, and she continued to cry softly.

“Nothing?”

“We have no more credit. We haven’t produced enough.” I knew now what he was talking about. We didn’t really deal in money all that much in the settlement. Instead, a running tab of plus or minus would be kept at the store. When we had peanuts or other produce to sell, our number would go up. Then when we bought, it would go down. Apparently it was so far down that they wouldn’t give us any more bread, any more food.

We have no food, I realized. Disappearing from their door, I went to the kitchen (a separate building) and decided to check it out for myself. There was some sugar but no flour. Without flour, you can’t make bread. It was winter, and we weren’t harvesting anything. We have no food, I realized. Fear gripped me and hit me harder than any of the north winds ever had.

I heard something and had to look. Hiding beside the door, I saw Dad heading to the barn. His head was hanging low, and his stride was stunted, and—I wasn’t sure how to describe it. Somehow he looked small, as if the weight of the world was pressing his shoulders down into the ground.

Mom hadn’t left the house, and as soon as Dad made it to the barn I made my move. Scrambling out of the house and running full tilt to the other side of the barn, I moved into position to watch. With his back to me, he headed to where we kept the horse food. It was called kafir, a grain grown specifically for horses. Its grey-white cob wouldn’t do for human consumption.

But—what was he doing?

He was pounding the kafir into a powder. His work was laboured, deliberate and methodical. It was an act born out of desperation, an act of submission that a father never wants to have to resort to for his own children. But when there is no other option, the food for horses can become food for humans.

Baked into something resembling bread, the kafir tasted awful. It was a dense consistency and could probably have been used as a hammer. In order to make it even remotely palatable, Mom sprinkled it in water and added a half teaspoon of sugar. It was the only way we would eat it, and for the time it was the only food we had. When it hit my belly, I realized just how desperate we were. No produce. No credit. No flour. Nothing but kafir. I didn’t resent the situation we were in, but seeing Dad’s concession made me realize that God cares deeply for his children and wants to give them bread to eat.

* * *

Our homestead was one of 20 in the village of Friedensfeld, a kilometre-long stretch of road divided into farms 100 metres wide. Each farm was one kilometre deep, though some had land beyond it. It was modeled after the Russian settlements from which the families had all come, and how much space you had for agriculture depended on where the bush started on your land. Over time the bush would be brought down and the farms expanded, trying to push the amount of food we could produce. This village—Friedensfeld—was in the settlement of Fernheim in the Chaco, a small section within the country of Paraguay. It was (and continues to be) a country that knows what it means to be poor.

* * *

Before Dad owned the world’s first hybrid truck (a Chevy motor with a Ford body can be considered a hybrid, can’t it?), our family had only one bike. It was a beautiful black Heidemann single-speed adult-sized bike. As a young kid I would see my older siblings hop onto it and pedal off, and I was desperate to copy them. Not one to take labels (like adult-sized) to heart, I decided that I was going to ride the bike, no matter what came in my way. The problem was I was five years old and much, much too short.

But that wasn’t about to stop me.

An adult would climb onto that bike by swinging a leg over the bar, sitting on the seat and pedalling the way it was designed to be done. Not me. Since my head was barely higher than the seat itself, that wasn’t an option. But a bike isn’t a completely solid object, and the middle of a bike happens to be a large hole. For me, this was my opportunity. Slinging my leg through the triangle formed by the bars of the bike, I could get both my feet on the pedals if the bike was tilted 20 degrees to the side. My back end would be sticking out in the air, my head was under the handlebars in order to be able to see, and my arm had to stretch across to grab the opposite handlebar, but I was biking.

And that was all that mattered to me.

It was 500 m to my grandpa and grandma’s house down the dirt road, which had more bumps and potholes than anything I’ve ever seen in Canada, but I was determined to get there using my bike. With my body positioned like someone doing yoga, I pedalled as fast as my little legs would take me. One of the older men in the village couldn’t stop laughing as I rode by, shaking his head.

“That kid has determination like nobody else I’ve ever seen,” he’d say. It was uncommon for a kid to ride a bike—never mind an adult bike that was far too big for him. My determination set the stage for more struggles, challenges and victories to come in life.

* * *

The horse’s hooves beat the ground beneath us in a rhythm that I had become familiar with. The reins were gripped tightly in my hands, my brother hanging on to the horse without his hands behind me. The kafir fields stretched out before us, and we leaned forward with excitement. We hit the beginning of the kafir and started screaming. Galloping beside the field, we let our lungs take control of the situation. Sometimes the yelling was words, sometimes it was just noise.

As soon as we began yelling, the horse pounding the ground beneath us, there was a reaction. From amongst the stalks, hidden until now, came the sudden whooshing and beating of the wings of hundreds of pigeons. Afraid for their lives, they took off into the air. They had been sitting on the tops of the stalks, pecking away at the kafir. Since it was the food for our horse and part of our livelihood, it was our job to protect it.

Not to mention that it could also be a lot of fun.

We got to the end of the row and pulled up, turning around. They had settled on this side now, and we went back at it, leaning forward and making our throats hoarse. More pigeons took off. They usually fled at our noise. I pulled the horse up short, reining it in with instinct. We stood still, beside the kafir. My brother didn’t have to ask or speak; he knew what I had seen. Up ahead was a flock of parrots, still on the kafir. They didn’t flee as quickly, but that was OK. We didn’t want them to. Art leveled his slingshot at the bird, taking aim. He was shooting over my head, and with action born of experience I ducked down so the bullet wouldn’t hit me.

The shot was true and the bird fell off the stalk with a thud. It was flopping on the ground, and I had to move quickly. If it regained its senses and took off, it would all be for naught. I dropped from the horse and darted between the stalks, picking it up and flinging it on the ground. The slingshot bullet and the impact of the ground was enough to finish it off instantly.

“You got it?” Art’s voice rang out.

“Got it!” I called back, celebratory.

“Good,” he responded. “Get the beak.”

I reached down and grabbed the top of the parrot’s beak. Without the beak, we had no evidence that we had killed the parrot. Without the evidence, we couldn’t get paid for killing it.

With a quick cut from my pocket knife the beak came off, and I took the top half. I brought it back to my brother, handing it up to him on the horse. The horse whinnied and snorted, stamping its foot. It wanted to move. And we wanted to hunt, so my brother quickly dropped the beak into the shoe-polish container, and I climbed back up onto the horse, swinging up easily and lightly.

The hunt continued, each parrot’s beak worth seven cents from the mayor of our village. A single hunting trip could net 10 to 15 parrots, more money than we could earn from any other job we could find.

* * *

Right from a young age my life included working on the farm. Chores were common and included bringing the cows in at the end of the day, watering the horses, feeding them, collecting eggs from the chickens, cleaning the yard, weeding and raking. Making money was no simple task. In order for my parents to get us gifts for Christmas they had to sell eggs outside of the market, egg by egg, penny by penny. Since our society dealt only in a line of credit (and ours was so bad they couldn’t buy gifts), this was the only way for them to buy us a gift. They’d work at it the entire year, earning enough from eggs that we didn’t get to eat for a simple gift.

Just like any other kid, I had a wish every year for Christmas. But unlike most kids, my only wish was the same every year: a soccer ball. It’s not that I didn’t get one—I sometimes did—but I used it so much that I would need a new one by the next Christmas. The balls were simple and plain, and they’d bounce in every direction off the mud clumps that decorated the landscape.

On our property was a large bottle tree, with gigantic needle-like points coming off of plum-sized protrusions. One bounce off the bottle tree and a ball was popped like a balloon.

But the game didn’t end there. With no other access to sporting equipment, we’d open the ball up and patch the rubber bladder with bike patches, then close the material up and sew it together. It was probably the only time in my life I’d ever be caught with a sewing needle in my hand. Given to us at Christmas, the soccer ball would become a project throughout the year. Patched up over and over, we could often stretch out its tough existence until the next Christmas, when we’d hopefully have a new one.

My brother is three years older than I am, so by the time I was getting seriously into playing soccer he was already in junior high school, living in a dorm a significantly distant 9 km away. I was the youngest of ten kids (nine made it through infancy), and my brother was the second youngest. Older than him were my sisters, leading to my far-older brother at the top of the food chain, who had gotten married when I was six and was subsequently gone from home.

Some of my soccer playing was done with my two friends, Jacob and Abram, but they were nowhere near as enthusiastic about sports as I was. Given their lack of interest, it wasn’t long before my skills distanced me from them. With only 20 homes in our village, there weren’t too many other kids to play with.

Our farm was on the edge of the village, and some 500 m away was a native reserve. There were somewhere between 50 and 100 people living in the reserve, and their livelihood came mostly from begging or being employed by the farmers in return for food and (possibly) some money. They were quite frequently dependent on handouts or job opportunities, and the faith-based nature of our village led to us seeing them as poor whom we could help. Given that they were South Americans, soccer was something they were very interested in.

Finally I had someone to play with.

While we would have considered ourselves far from wealthy, I was the only one around with a soccer ball. Over time I had cut some small trees and built soccer goals, and we’d set them up on the cow pasture behind our farm. Right there, in my own backyard, we had our own official soccer field. Saturdays or Sundays were game days, and I’d wake up in the morning with an itch in my legs to get out onto the field, test my skills out against the natives, and have a real game. The size of the scrimmage would vary from day to day, though it usually hung around the 4 to 10 players range. It didn’t matter to me, as long as I was playing soccer.

It was the closest I would come to a real game of soccer for a long time.

* * *

Once or twice a week wasn’t enough. I wasn’t a cocky kid, but I had a drive to succeed like no one else I knew. This meant that I needed to practice, even if no one else wanted to. Since my brother was off at school (sometimes home on the weekends) and my friends weren’t as interested in the activity as I was, it meant I needed to come up with something on my own, a way to train and get better without relying on anyone else. If I had wanted to play forward or defense it would have been easier, but I always found myself gravitating to the net. You can dribble, deke and shoot without anyone else on the field. But it’s hard to make saves if all the ball does is sit on the ground.

Our homestead was four buildings: two barns, the house and the kitchen (separate from the house). The kitchen was the only building with any type of heating at all—it had a simple woodstove. While it didn’t often go below zero Celsius in the winter, zero Celsius is very different when all you have to do is run from your car to the house than when you have to cover yourself up under a blanket and go to sleep in a house that isn’t remotely insulated. That combined with a dry and strong wind that whips into the house and brings with it sand and dust can make for a very uncomfortable winter.

While the barns were often built with wood planks, the homes and kitchens were built out of mud bricks with straw in between. The mud would be packed into a brick form, let dry and pulled out once it was dry enough to retain its shape. Then it would finish hardening out of the form. Anyone who’s stood in a mud field knows well enough that with rain mud turns soft and gooey, completely losing its shape. To combat this we would coat the bricks with a chalk-like paint to seal them. This meant the rain stayed out (mostly) and the houses would stand for longer. This paint was white, and the chickens had it in their minds that this was food. They would peck away at the white chalk until they’d thoroughly weakened the house, so everyone resorted to mixing soot into the bricks along the bottom of the house, preventing the chickens from pecking at it. The roofs were made of tin or aluminum, but it was the walls and not the roofs that I was interested in.

Patterned by design and weathered over the years, the walls were often irregular and unpredictable—perfect for a goalie. To hone my ability I would kick the ball against the walls. The ball bounced back at me to the left, right, up, down—I could never predict it. Over time I got better and better at reacting to the bounces and I could stop it from flying past me. I had to be sharp, ready on my toes to make the catch or block. Depending on how close I stood I’d have to do more than step—I’d have to resort to lunging and diving after the ball, scraping and bruising my legs, sides, hips, shoulders and arms countless times.

But it was all worth it to stop the ball from getting past me.

And it was preparation for a hobby and career of using my physical gifts and strengths to reach others with God’s good news.

It was on that mud yard behind the barn, flying through the air, that I developed a saying I’ve become known for (among my family, at least): If you can touch it, you can catch it. (The catchphrase worked great when my kids were small, but eventually they caught on and realized they could repeat it to me mockingly when I dropped anything thrown at me.)

A soccer goalie only faces a handful of shots in a single game, so controlling the shot is of the utmost importance. If you don’t hang on to it, the ball bounces right back out into the 18-yard box. Your defender might get it and clear it away or send it to the sidelines, but it might also end up at the foot of an attacker. With the large size of a net, they’ve got a lot of options for putting it behind you. I began to develop the ability to turn any contact with a shot into a catch. When you consider the size of a soccer net (or no net, as it was for me when I kicked the ball off the side of the barn) and the relatively small percentage of the net the goalie’s body covers, it’s quite remarkable how low-scoring a soccer game truly is. But stretch out the goalie’s body in the middle of the air and somehow he can reach a little farther if he needs to. The ball touches just the finger, and somehow he can bring the hand around to make the catch.

Without an attacker’s face to analyze or eyes to look into, everything that came off the side of the barn was a guessing game. I began to develop the ability to anticipate the ball’s angle and react in a split second. Over time it was something that would set me apart from many other goalies.

But that’s getting ahead of the story.

* * *

School in my village was a one-room experience. For the 20 farms there was one teacher, and he covered everything from grade 1 to grade 6. If you were destined to take over your parents’ farm and needed to get to working, grade 6 was often as far as you would go. Since there weren’t very many people in the village, the school began and took place on a rotating basis. One year it would be grades 1, 3 and 5. The next year it would be 2, 4 and 6. This meant that the teacher only had to juggle three curricula at a time instead of six. But it also meant that, if you weren’t quite old enough (six) when it was a grade 1 year, you had to wait two years to get into grade 1.

That was me.

So I began grade 1 an entire year behind most North Americans. In our grade 1 class (though two birth years because of the delay) there were four of us: my friends Jacob and Abram and a girl named Annaliese. There were usually somewhere between 10 to 15 kids in the entire school, so it was a completely different experience than anything you’d typically see in North America.

* * *

The morning was the same as any other, though my feet didn’t walk to the school with the same bounce and spring they usually did. When Jacob and Abram came running by, I didn’t run with them. The walk seemed to stretch into an hour, the school building looming and seemingly ever-distant.

The first subjects came and went the same as they always did, but my attention wasn’t quite there. Along with all the usual subjects, we also had singing. This was fine when the 15 of us in the classroom were singing together. But today was different. Today our teacher was going to be testing us. And testing meant that, one by one, we would have to sing.

As it came around to my turn, my hands began to sweat. Stand me in front of a soccer net with a ball whistling at my head and I was in my element. But this, this was unbearable. I had already chosen my song, one of the only ones I could adequately remember, and started out by singing loud enough that all could hear, “Hanschen Klein ging allein in die weite Welt hinein,” translated as “Little Hans went into the wide world alone.”

Towards the end of the first verse my volume had already diminished, and I was fading.

“You can stop,” the teacher said.

I nearly bit my tongue, I stopped so fast.

Abram was whispering to Jacob, and I couldn’t hear what he was saying.

“I know more of the song,” I said, though I didn’t want to sing. I just didn’t want to hear what he would say next.

“That’s okay, Arvid,” he responded. “You failed.”

I could hardly believe it. It was grade 2, and it was the only time I had ever failed a test—and remains that way to this day.

Some of the people in the class laughed. He hadn’t even given me a chance. “You should really only sing when you’re alone.”

To this day I have listened to him. If those around me in church were to all of a sudden stop singing, you wouldn’t be able to hear me. I move my lips, but hardly any sounds come out.

* * *

If things weren’t going well in music class, gym was a different matter. The volleyball court was split down the middle, and the teams were lined up on the sides. Even though I was younger than a lot of the students in the school, I was always picked near the top. The team captain was on the opposite side from his team, standing at the back line of the volleyball court.

The game of dodge ball started, and I moved away from the centre of the court, standing near the sidelines. It was the best vantage point. Only from there could you see the entire team—on my left—and their captain—on my right. Since the team could lob balls to their captain, the attack could come from any side. One came at me from the right, aimed down at my feet. I dodged it deftly, avoiding being hit while moving across the centre of the court so as not to remain a stationary target too long. I pulled up on the other side, glancing left and right. The captain was usually the strongest player, so you had to be wary of him. But there were numerous attackers on the other side of the court, so you had to keep an eye out for them as well.

Because of my speed and skill, it didn’t take long for them to start attacking me. A few of the weaker players would already be hit, though they didn’t have to leave the court. Getting hit meant your team lost a point. Catching the ball meant you gained a point—and this was where I became the biggest dodge ball star Friedensfeld had ever seen.

Another throw came at me, and I started to move. It was coming too fast, and my hands snapped up to catch it. I wasn’t fast enough, and it bounced off my arm. The other team was already celebrating—this was early in the game to have a hit against me. But the ball had lobbed up and away, and I reacted quick. With a dive like a soccer goalie, I flew through the air with my hands outstretched. I caught the ball between my hands and cushioned the landing, rolling back up onto my feet, ready to dodge again or attack the other team.

“Nice one!” Jacob called out. The other team jeered but didn’t have much to say.

“Stay alive!” I called back to him, jumping over another throw and spinning to face their captain at the same time. I had seen the ball lobbed to him over my head and knew an attack would be coming. Just as he cocked his arm back to throw, I dropped the ball in my hands and maintained my position. From only 15 feet away I reacted quickly and caught the ball, gaining my team another point. They cheered, and I smiled. Frustrated, their captain threw another ball wildly in my direction as the game came to an end.

We had won, my last-second catch the deciding point.

The training against the barn wall had honed my reflexes, and dodge ball had made my hands a trap for any ball that came near me. Combining these two skills laid the groundwork for the years to come.

* * *

Dad never gave up on his dream of coming to Canada. Though the process would span several decades, it was finally coming to a head as I went through elementary school. When the school year finished (in November) after my grade 6 year, we thought the process was almost complete. We would be moving. With time, we would become Canadians. The religious persecution that had forced Dad to flee Russia combined with the health concern that prevented him from going directly to Canada had meant long and hard years in Paraguay. Canada looked like the Promised Land, and for many of us it was. But just like the Israelites, we were delayed for a while during the time that things sorted themselves out.

Because we were almost accepted, I didn’t go to grade 7 nine kilometres away when the school year started again in February. We were going to be going to Canada, and I’d be joining the school year there.

* * *

Our long journey to Canada was delayed, again. This time, thankfully, only until the winter (Canadian summer). In August of 1970 we set out for Canada, elation evident in the smiles on our faces as we boarded a plane for the country of promise.

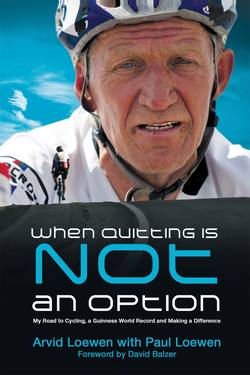

Arvid, standing on the cistern in a family photo. Note the Heidemann bike Arvid rode as a 5-year-old.

With his parents, sitting on the Ford/Chevy hybrid truck

Arvid in the centre of his family photo wearing a plaid shirt