Читать книгу Hollywood Hoofbeats - Audrey Pavia - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

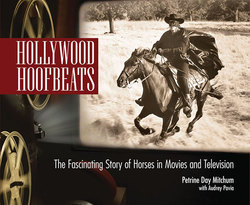

Robert Mitchum rides Steel in their second film together, West of the Pecos, 1945.

Hollywood Hoofbeats represents decades of research, not only the fourteen years I and my indispensible co-author, Audrey Pavia, collectively spent uncovering amazing stories but also years of work by film historians, journalists, movie buffs, and horse lovers. To these we owe an enormous debt of gratitude.

My own journey down the Hollywood Hoofbeats trail began in 2000, when I began researching a documentary film for a colleague. The film never materialized, but I was hooked on the subject of horses in film. As a child, my favorite TV shows were Westerns and National Velvet, and I was lucky enough to grow up on a horse farm and have my own pony. But I never thought of horses as actors.

Actors? Actor is not a word that usually springs to mind when contemplating the many roles horses have played in our history. Their contributions to mankind have been well chronicled and celebrated in the arts, yet we rarely think of horses as entertainers. Since the rise of the internal combustion engine, however, horses in developed nations have flourished primarily as sources of amusement rather than labor. Equestrian sports may be big business, but their real raison d’etre is entertainment. Wild West and Civil War reenactments, medieval jousting exhibitions, and a variety of touring equestrian shows have been enthralling audiences for decades. So have horses in movies. But actors?

As my research of movie horses expanded, I discovered what I had long suspected: some horses are natural actors. In my childhood, my family owned a big bay Quarter Horse named Woody who feigned lameness to avoid work. One day he would be lame on his right foreleg, the next day on his left. There was nothing detectably wrong with Woody besides a preference for his pasture over the saddle.

Unlike Woody, movie horses—the good and well-treated ones—love their jobs. Time and again, the men and women who have worked with equine actors—the trainers, wranglers, stunt performers, actors, and directors—told me stories of horses who knew when the camera was running and took direction with uncanny awareness. I heard tales of specially trained stunt horses who loved to show off, and lived long and pampered lives. I also heard about equine star tantrums and unruly performers whose diva behavior was tolerated because of their box-office cachet.

It is true that stunt horses were sometimes subjected to cruelty in the past and that far too many equine fatalities occurred in the name of entertainment. It is also true that there were movie horse trainers working in silent films, and the early decades of filmmaking, who today would be called “horse whisperers,” a moniker they would most likely mock and modestly reject. The best trainers currently working in the film industry utilize the same basic methods of those film pioneers.

Hurried production schedules have not always allowed for the time needed to properly train horse actors, but overall conditions for equine thespians—and all performing animals—have vastly improved in recent decades thanks largely to the vigilance of the American Humane Association’s Film and Television Unit. These days it is considered de rigueur for the AHA’s certification to appear in the credits of any film that utilizes animal actors.

There’s that word again. Actors. In the course of writing Hollywood Hoofbeats, I watched scores of movies. Certain horses stood out from film to film, and I developed favorites: a black-and-white Paint named Dice, whose deadpan expressions belied his hilarious tricks; Highland Dale, a stunning black American Saddlebred stallion who, unlike old Woody, learned to limp on command and won numerous awards during his long career; Steel, a handsome blaze-faced chestnut gelding who supported a galaxy of Hollywood stars. One of these was my father, Robert Mitchum, who lied to the producers of his first western, Hoppy Serves a Writ (1943), and told them he could ride. He learned on the job—barely—and when he won his first starring role as Jim Lacy in Nevada (1944), the producers were smart enough to pair him with a seasoned equine actor, Steel. They made two movies together.

Watching so many films of multiple genres, I began to realize that the movies as we know them would be vastly different without horses. There would be no Westerns—no cowboy named John Wayne!—no Gone with the Wind, no Ben Hur, no Dances with Wolves, no Gladiator, no Seabiscuit or The Black Stallion. In fact, the movies might not exist at all since the entire motion picture industry evolved from an experiment with a camera and a horse.

While it is virtually impossible to cite every horse who left his mark on celluloid, with Hollywood Hoofbeats, I have attempted to pay tribute to the spirits of the marvelous equine actors who have traversed cinema’s varied terrain since its inception.

Petrine Day Mitchum

Santa Ynez, California, March, 2014