Читать книгу Hollywood Hoofbeats - Audrey Pavia - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2. A Horse and His Man

“A cowboy is a man with guts and a horse.”

—Attributed to Will James

The Majestic Silver King and Fred Thomson

Since his auspicious debut in the birth of cinema, the movie horse has enjoyed a long canter in the limelight. During the silent film era, 1893–1930, the horse achieved a type of stardom that seems unbelievable today. Even more remarkable, his star power endured for decades. Spurring that rise was the creation of the cowboy-horse partnership. The right man paired with the right horse could make both idols on the silver screen. For some Western fans, the horse was the bigger box-office attraction. Roy Rogers, the great cowboy star of the 1940s and 1950s, who became identified with his palomino stallion, once quipped, “I have no illusions about my popularity. Just as many fans are as interested in seeing Trigger as they are in seeing me.”

Long before Roy Rogers and Trigger became celebrity icons, however, a dour Western actor and his red-and-white pinto pony, William S. Hart and Fritz, established the cowboy-horse partnership in a series of gritty silent films. Following on their heels was a new breed of Western stars—real cowboys such as Tom Mix and Ken Maynard. One horse, a charismatic stallion named Rex, bucked the formula and fought his way to the top alone.

The inimitable Fritz and Hart are seen in the California Desert.

The First Partnership

Like his predecessor, Broncho Billy, William S. Hart hailed from the East and would establish a screen persona as a “good/bad man.” The similarities stop there, however, as Hart had a genuine love of the West and horses. He had spent much of his childhood, in the late 1800s, traveling with his miller father and observing the ways of the disappearing Old West. Living for a time in the Dakotas, he learned good horsemanship and a respect of nature from his Sioux playmates. These childhood experiences would translate into an almost fanatical quest for realism in his films and result in the depiction of interdependent friendship between man and horse.

Before making his first movie, however, Hart spent two decades on the stage, in New York and London, and earned renown as a dramatic actor. His work in two plays about the West, The Squaw Man and The Virginian, helped create his film persona.

Hart’s early movie horse, Midnight—which the star described in My Life East and West as “a superb coal-black animal that weighed about 1200 pounds”—was considered hard to handle. Hart got along with the horse and tried to buy him for $150, a large sum in 1914. He belonged to the traveling Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West Show, which during its off-season leased stock to the New York Motion Picture Company’s California production arm. When Joe Miller refused to sell the horse, Midnight hit the road with the 101 Show, and Hart began searching for another mount. Hart soon found himself drawn to a small pinto named Fritz, who was to become the equine half of the first screen cowboy-horse buddy relationship.

Ann Little began her career in Broncho Billy Anderson serials. She appeared in a series of Westerns for Universal, starting in 1915. She displays her cowgirl skills in this photo circa 1913–15.

Enter Fritz

A Sioux chief named Lone Bear reportedly brought Fritz to California in 1911. Hart first set eyes on the red-and-white gelding at Inceville, producer Thomas Ince’s movie ranch. Fritz was practicing his rear with actress Ann Little aboard and almost came down on Hart’s head. Despite the close call, Hart was smitten—not with Ann but with Fritz.

Though Fritz was small, weighing only about 1,000 pounds and standing just over 14-hands high, Hart saw something special in the little horse. In their first film together, the sturdy pinto impressed the actor with his stamina. The script called for Fritz to carry the 6-foot Hart and another actor, who with their guns and the heavy stock saddle must have weighed close to 400 pounds, for hours. The action culminated in Hart’s “falling” Fritz and then using him for a shield in a gunfight. The actor related in his autobiography that the brave but weary little horse gave him a thankful look that “plainly said: ‘Say, Mister, I sure was glad when you give me that fall.’”

Fritz apparently didn’t mind falling, as Hart regularly threw the pinto from a dead run, using a technique that has been traced back to the armies of Alexander the Great. In an era when tripping devices were commonly used in the movies, Fritz was one of the first trained falling horses.

Because of his markings, Fritz could not be doubled, so he performed every stunt himself—including jumping though windows and fire—except one. In Fritz’s last film, The Singer Jim McKee (1924), an elaborate replica of the pinto was painstakingly constructed (at the then-huge cost of $2,000) to take his place in a fall from a cliff into a deep gorge—a deadly drop of about 150 feet. Hart galloped Fritz to the edge of the cliff, then pulled him into a fall. Once the pinto was safely removed from the scene, the mechanical horse was brought in and held upright with piano wire for Hart to mount. When the wires were cut, Hart and the dummy tumbled over the precipice. While Hart was badly shaken by the fall, Fritz would not have survived it without serious injuries. The final edited sequence proved so convincing that the board of censors, headed by William Hays, president of the newly established Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America, summoned Hart to New York, certain he had endangered a live horse. Once he explained how the astonishing illusion had been accomplished, the censors were placated, but when the film was released, it still caused a flood of mail from Fritz’s concerned fans.

William S. Hart discovered his equine partner Fritz at Thomas Ince’s movie ranch, Inceville, circa 1915.

From 1916–1918, William S. Hart’s movie ranch was on the Santa Monica site of the former Inceville.

The Greatest All-Around Horse

Hart adored Fritz, whom he described as “the greatest all-around horse that ever lived.” Two of Hart’s films, The Narrow Trail (1917) and Pinto Ben (1924), were made as tributes to the pinto. Hart even ghostwrote a book, Told Under a White Oak, published in 1922 and “authored” by Fritz. The charming book tells Fritz’s version of all the hard stunts he had performed during his career.

The actor was determined to buy Fritz, but his owner, Thomas Ince, refused to sell, figuring he could keep Hart under contract using the pinto as leverage. Hart outfoxed Ince, however, and made his purchase of Fritz a condition of a contract negotiation, then later withheld him from fifteen films to leverage a higher salary. Since early films were made quickly, Fritz was only out of the public eye for about two years. Fans missed their favorite movie horse, but his absence made his return, in 1919’s Sand, all the sweeter.

For all his sturdiness and willingness, Fritz had a temperamental streak. One of his quirks was his attachment to Cactus Kate, a feisty mare used in bucking scenes. Hart was obliged to buy the mare to keep his costar happy. On one particular day during the filming of Travelin’ On (1921), Kate had been left at the studio barn with another stablemate, a giant mule named Lisbeth. Fritz had several difficult scenes with a monkey and refused to work until the mare was brought to the set. With Kate watching from the wings, the shooting proceeded beautifully until a terrible bellowing and thundering of hooves interrupted work. Lisbeth had broken out of her corral and galloped a mile through traffic to join her friends.

Fritz was retired to Hart’s ranch in Newhall, California (now a museum), in 1924 and thus did not appear in Hart’s last film, Tumbleweeds (1925). When the horse died at age thirty-one in 1938, Hart had him buried on the ranch with a huge stone marker that still reads, “Wm. S. Hart’s Pinto Pony Fritz—A Loyal Comrade.” In a monologue added to the 1939 rerelease of Tumbleweeds, the Shakespearean-trained actor gave a heartfelt speech honoring his lost horse.

Audiences had loved Fritz almost as much as Hart had, and savvy filmmakers were on to a winning combination. By the time Fritz made his last fall, the long parade of cowboy-horse screen partnerships had begun.

Fritz brings William S. Hart luck as he played a dice game between takes on the location of Riddle Gawne (Aircraft, 1918).

Ride ’Em Cowboys

With the Old West disappearing and the Western film flourishing, a new breed of actor rode onto the scene—literally. Many expert horsemen looking for ranch work at the turn of the century wound up displaying their skills in the traveling Wild West shows. As the popularity of these shows began to wane in the early 1910s, a number of cowboy performers moved on to the picture business. Rodeo stars were also lured to Hollywood by the promise of greater fame and fortune—or at least a steady paycheck doing stunt work. College athletes traded their track shoes for cowboy boots to cash in on the craze for hard-riding heroes. Thespians who weren’t born in the saddle quickly took riding lessons to get in the game, and playing cowboys catapulted a few actors to wider movie stardom. The first big Western star after William S. Hart, Tom Mix, was, however, a genuine cowboy.

Tom Mix and Tony

Tom Mix would come to be considered—by his cowboy contemporaries as well as by many modern film buffs—the best horseman of all the movie cowboys. Mix, born in Pennsylvania in 1880, learned horsemanship from his father, a stable master. Young Tom became an excellent rider. He also exhibited a theatrical flair and created his own cowboy suit when he was just twelve years old.

At eighteen, Mix joined the army for a three-year stint. He reenlisted but went AWOL a year later when he got married. He worked a variety of jobs, including wrangler, until he joined up with the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West Show in 1906. Mix became one of their top performers. Four years later, he hooked up with the Selig Polyscope Company to make Western movies. A Selig press release for the 1911 film Saved by the Pony Express stated: “The mounting and riding at full gallop of Western horses, and of an unbroken bronco by Tom Mix, are some of the most thrilling feats of horsemanship ever exhibited in a motion picture.”

Mix rode many horses in the 170 films he made for Selig. His first one, a stout brown gelding, looked like a real ranch horse and obviously derived his unusual name, .45, from the brand on his left hindquarters. Mix’s avowed favorite movie mount was his own horse, Old Blue, a tough little roan with two hind socks and a long dished face, typical of Arabian breeding. (It is not known whether this sturdy little gelding actually had Arabian blood.) Old Blue was so loved by Mix that when the horse had to be put down after breaking a leg in his corral at age twenty-two, the star was bereft. He had the roan buried at his ranch, Mixville, in Edendale, California, where many of the actor’s Westerns were filmed. Ever faithful to “the best horse I ever rode,” Mix placed a wreath on Old Blue’s grave every Decoration Day.

Tom Mix and his horse .45.

Tom Mix and his most beloved horse, Old Blue, as is clear from his heartfelt inscription on the photo.

By 1920, Mix was challenging William S. Hart for the cowboy-hat crown. The former’s early penchant for clothes had evolved into a flamboyant style, the antithesis of Hart’s gritty, authentic look. Mix’s movie persona was lighthearted and imbued with clever tongue-in-cheek humor. Audiences responded enthusiastically to Mix, but still something was missing—an equine sidekick as flashy as the man who rode him.

Enter Tony, “the Wonder Horse” Many stories have been circulated about Tony’s origins. They usually involve Tony’s being noticed as a colt, following his mother as she hauls a vegetable cart. Inevitably, Mix buys Tony for $10 or $12. The foggy details of the colt’s metamorphosis into the Wonder Horse imply that Mix himself trained Tony. However, the most convincing version of how Tony arrived in the actor’s life comes from Mix’s third wife, Olive Stokes. She claimed to have spotted the colt one day in 1914, as he followed a chicken cart being pulled by his dam along Glendale Boulevard near downtown Los Angeles. She contacted Pat Chrisman, Mix’s horse trainer, who lived a few blocks away. He liked what he saw and paid the cart driver $14 for the future Wonder Horse. Mix bought Tony from Chrisman in 1917 for a reported $600. Although the actor boasted that Tony did not have to be trained, just shown what to do, Chrisman taught Tony the many tricks that made him famous.

Tony appeared with Mix in a 1917 Selig film, The Heart of Texas Ryan, when the horse was three years old; it was not until Old Blue’s demise in 1919, however, that the actor began using Tony as his main movie mount. A sorrel with a long blaze and snip and two hind stockings, Tony appears to have been an American Quarter Horse type. He was highly intelligent and, like his master, had a quirky personality. According to director George Marshall: “Tom was temperamental, but it ran in streaks. Oddly enough, the horse, Tony, was very much like his owner. Pat Chrisman would rehearse him in some tricks for a picture and he would perform beautifully, but when it came time to shoot—nothing! He could be whipped, pulled, jerked, have bits changed, but still no performance. Come out the next morning and he would run through the whole scene with barely a rehearsal. Then he’d look at you as much to say: ‘How do you like that? Yesterday I didn’t feel like working.’”

On screen, however, Tony was always a loyal comrade. He was probably the first movie horse depicted as possessing a sophisticated knowledge of the English language, not only simple phrases such “whoa” or “good boy” but also whole sentences, usually directing him to perform some task. While horses can be trained to respond to certain repetitive phrases, this anthropomorphizing was pure fantasy. Audiences loved it, and from then on many actors talked to their horses and the horses were shown responding as if they really understood.

Tony, “the Wonder Horse,” was expert at helping Mix out of jams, rescuing damsels, and participating in thrilling stunts. Mix was well known for performing his own stunts. This was partly myth; the actor did have doubles for certain stunts. So did Tony. His doubles, made up to mirror his distinctive markings, performed jumps and falls in his place. A large mare, Black Bess, was used in long shots as her size read better on film. Still Tony often took risks along with his master. On one film, a dynamite blast, ill timed by the special-effects man, threw Tom and Tony 50 feet and knocked them unconscious. Tony suffered a large cut; Mix’s back reportedly looked as if he’d been hit by shotgun pellets.

For his efforts, Tony, “the Wonder Horse,” commanded costar billing and received his own fan mail. One letter addressed simply to “Just Tony, Somewhere in the U.S.A.” was duly delivered to the Mix ranch. He was the first horse to have his hoofprints imprinted in the forecourt of Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood, alongside the foot and handprints of Mix and other biped movie stars. Tony’s popularity was so great that three Mix films used his name in the titles: Just Tony (1922), Oh! You Tony (1924), and Tony Runs Wild (1926). Tony even “contributed” to a 1934 children’s book, Tony and His Pals.

Tony was utilized in many publicity campaigns and in one gag shot was shown getting a manicure and permanent wave for his appearance at New York’s Paramount Theater. He accompanied Tom on a 1925 European publicity tour, during which, according to a letter from Mix to his fans in Movie Monthly magazine, “Tony was patted by so many people it’s a wonder he has any hair left.”

Among the first stars to be merchandized, Tom Mix and Tony were immortalized as paper dolls.

Tom Mix and Tony make a handsome pair.

After placing his hoof prints in cement at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, Tony waits for his man Mix to sign his name.

Tony Jr. Takes Over Although Tony’s retirement was officially announced in 1932, his last credited role was in FBO Pictures’ The Big Diamond Robbery in 1929. When Mix returned to the screen in Universal’s 1932 talkie Destry Rides Again, he rode a new mount, Tony Jr. (no relation to his namesake). Like his predecessor, Tony Jr. was a sorrel, but he was more striking than Tony, with a wider blaze and four high stockings. He may have been sired by an Arabian and purchased by Mix from a florist in New York in 1930. Tony Jr. made his first known appearance on January 6, 1932, in a publicity shot with Mix, who was recuperating from illness at home on his fifty-second birthday. Despite the obvious differences in the horses’ markings to the trained eye, Universal passed the new horse off as “Tony” and continued to bill him as such through the first half of 1932. Tony Jr. finally received billing as himself in a fall release.

The newcomer achieved his own popularity with audiences and critics. In a 1933 review, a New York Times critic wrote, “Tony Jr. was as fine a bit of horse flesh as ever breathed.” Unfortunately, Mix was on his way out when Tony Jr. arrived on the scene, and it is unclear what became of him after Mix’s death in a solo auto accident in 1940. The original Tony, however, had been provided for in Mix’s will and survived his former costar by two years. On October 10, 1942, the failing thirty-two-year-old movie horse was put down in his familiar stall at the old Mix estate.

Tony Jr. poses with Tom and director B. Reeves “Breezy” Eason during Mix’s last film, a Mascot serial titled The Miracle Rider.

Buck Jones and Silver

Another veteran of the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West Show who transitioned to the silver screen was a rugged bronc buster and trick rider named Charles Gebhart. For the movies, he was rechristened Buck Jones.

While touring with the Millers’ show in 1915, Buck married fifteen-year-old trick rider Dell Osborne in a horseback ceremony. During World War I, Buck broke horses in Chicago for the Allies’ cavalry units. After the war, he and Dell performed in several Wild West shows and the Ringling Brothers Circus as trick riders. With a child on the way, they decided to settle in Los Angeles, where Buck found work in the movies as a bit player and stuntman, sometimes doubling his eventual rival and friend Tom Mix.

Buck had his first starring role in Fox Studios’ The Last Straw (1920), and his career skyrocketed. To compete with the other cowboy stars, however, he needed a special horse. His first horse, a black, unfortunately died in a filming accident. However, in 1922 Buck spotted a beautiful gray on the set of Roughshod and knew he’d found his movie mate. He bought the horse for $100 and named him Silver. He was to become almost as famous as Fritz and Tony.

Although Buck preferred action to cute antics, Silver got to perform enough tricks to satisfy audience anticipation while also providing thrilling images as he and Buck streaked across the Western terrain. Silver was so intelligent that he learned to perform stunts, such as leaping through fire, with only one rehearsal. His skill as a one-take actor became legendary.

Buck owned two other horses, Eagle and Sandy, who often doubled Silver. Eagle was usually used in long-shot galloping sequences; he can be easily identified as he swished his tail when he ran. Sandy was always used for rearing scenes. Almost indistinguishable from Silver, Sandy had a more photogenic head and was also used for close-ups. Buck loved all his horses and would never subject them to real danger. For hazardous stunts, unlucky rental horses from the studio stables served as doubles.

Buck Jones Productions produced only one film, a non-Western, before folding. The intrepid Jones rallied to put together the traveling Buck Jones Wild West Show. The Great Depression ended that enterprise prematurely, but the actor rebounded and returned to the movies. Though semiretired, Silver was occasionally brought in to do specific stunts. Eagle received billing in some of Jones’s later films, and Sandy was billed as Silver in the Rough Riders series at the end of Buck’s career.

Eagle, always prone to scours, was put down in 1941 after a particularly bad bout left him too weak to recover. When Buck returned from a trip to find Eagle gone, he shut himself in his bedroom and cried. Jones’s own life came to a tragic end in 1942, when he perished in a fire at a party being held in his honor in Boston. He died heroically while trying to rescue other guests.

A few months later, Silver began to fail. According to Dell Jones: “It seemed he missed Buck and stopped eating. He would bow his beautiful head and grieve. He was very old for a horse—thirty-four years.” Sadly, Dell had the old horse put to sleep. Sandy passed away a few months later.

The rugged Buck Jones with his elegant other half, Silver.

From the left, Buck Jones and his trick-riding stuntwoman wife Dell and their matching white horses at the 1939 Santa Claus Lane Parade on Hollywood Boulevard. Next to Dell is singing cowboy Ray Whitley and on the far right, astride the paint, is the trick-riding cowboy star Montie Montana.

Ken Maynard and Tarzan

Buck Jones’s chief rival was Ken Maynard, a native Texan known throughout the Wild West show circuit as an incredible trick rider and roper. He had made a brief attempt to steal Dell away from Buck, and the men never became friends. Maynard made his name in films aboard a palomino mount called Tarzan.

In 1926, Maynard purchased a ten-year-old gelding at a ranch in Newhall, California. The palomino was what would now be considered a National Show Horse, an Arabian/Saddlebred cross, and was given the name Tarzan at the suggestion of Maynard’s acquaintance Edgar Rice Burroughs, author of the novel Tarzan of the Apes. The popular film with the same title had come out in 1918, thrusting the name Tarzan into the minds of audiences throughout America.

Former circus trainer Johnny Agee taught the gelding a repertoire of tricks. Tarzan often had the opportunity to display his talents on screen, thanks to Maynard, who wrote such moments into the script. His humanlike qualities allowed the palomino to rescue Maynard from danger on more than one movie occasion. Like Tony, he was billed as “the Wonder Horse,” by all accounts an apt, if not original, nickname.

Tarzan was often doubled by one of eight palominos in Maynard’s stable. Though a daredevil rider whose stunts awed audiences, Maynard rarely put the real Tarzan in serious danger. Instead, the actor pampered his star horse and transported him in a custom trailer emblazoned with his name. Maynard and Tarzan successfully transitioned from silent to sound pictures, although the horse’s training in verbal cues, rather than visual signals, did create some production challenges.

Tarzan made his last movie in 1940, a film called Lightning Strikes West, when he was twenty-four. He was retired to Maynard’s ranch soon after and died that same year. Maynard buried him in an undisclosed gravesite, reported to be under an elm or a Calabash tree in either the Hollywood Hills or the San Fernando Valley. The grieving Maynard kept Tarzan’s death a secret for years. The actor never again achieved the success he had had when the great palomino carried him to stardom.

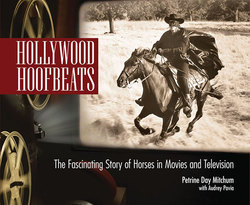

Fred Thomson and Silver King

Fred Thomson was a college athlete who won the national All-Around title at Princeton University in 1913. He eschewed the Olympics to pursue the Presbyterian ministry and became interested in movies while prescreening them for the Boy Scouts. In 1921, after a brief stint in the military, he became an actor. Inspired by Tom Mix, the handsome Thomson became a skilled equestrian, performed his own stunts, and made a star of his horse, a striking gray 17-hand Irish stallion named Silver King. True to his name, the stallion was one of the most spectacular horses to ever grace the silver screen.

The story of how Thomson and Silver King became partners may raise a few eyebrows given today’s emphasis on gentle training methods. Thomson was visiting a friend who owned a New York City riding school. Silver King caught the eye of Thomson, who was warned that the stallion was difficult. Undaunted, he took the horse for a ride in Central Park. When Silver King attempted to unload his rider by bucking, whirling, and trying to scrape him off on trees, Thomson responded by throwing the horse to the ground using a cowboy trick of tying his legs with one end of a rope and striking him repeatedly with the other end. Thus Thomson earned the respect of the spirited stallion, and the two became closely bonded. A week after this incident, the actor took Silver King to Hollywood, determined to make him a star. Stabling the stallion at his home, Thomson taught him many tricks, including sitting down, bowing, and performing the strutting Spanish walk. The stallion was a quick study and loved to show off. One of his admirers was the Thomsons’ friend Greta Garbo, who loved to sit on the corral fence watching Fred put the stallion through his paces. Once his lessons were learned, Silver King was ready for his close-up.

The stallion loved the camera, and although he seemed bored during rehearsals, he came alive once the director called “Action!” He played significant roles in Thomson’s films, and in keeping with the anthropomorphic trend, he appeared to understand and execute abstract demands. A natural box-office draw, he received costar billing. The advertisements variously read: “Fred Thomson and His Wonderful Horse—Silver King,” or “Fred Thomson and His Famous Horse—Silver King.”

In one of Thomson’s two surviving films, Thundering Hoofs (1924), Silver King shows his stuff by rearing on command, bowing, kneeling at a gravesite, untying ropes, and nudging Thomson toward his love interest. In the film’s most frightening sequence, Silver King is condemned to a Mexican bullring as a matador’s mount after Thomson’s character has been unjustly jailed. The giant bull gores the stallion, who appears doomed. In the nick of time, Thomson’s character breaks out of jail to save his horse by wrestling the bull to the ground. Silver King’s bravery in working with the bull can be attributed to the fact that one of his stablemates, and probable costar, was Thomson’s pet bull, Muro.

Silver King’s antics garnered plenty of attention from the Hollywood press, and the stallion often made headlines with his temperamental behavior. He reportedly threw tantrums if one of his doubles performed a stunt, and while docile as a lamb working with children on camera, he might kick the set to smithereens after “Cut!” was called. When Silver King showed up on a nighttime set wearing sunglasses, the gossip columnists went wild with speculation. Had Silver King gone “Hollywood”? It turned out that the glasses were intended to protect his eyes from the bright Klieg lights used in filming after he had shown signs of temporary blindness. Compresses of cold cabbage leaves and ten days in a dark stall reportedly cured him of “Klieg eyes.”

Silver King’s brilliant career was cut short when Thomson passed away suddenly in 1928 following a brief illness. Shortly thereafter, the Los Angeles Times ran a front-page story about Silver King’s mourning his master. The article called him “the most famous horse in the world.” Several years later, Thomson’s widow, the screenwriter Frances Marion, sold Silver King, and in 1934 he returned to the screen in low-budget films with Wally Wales, a little-known cowboy star. The marvelous Silver King received billing and was featured in publicity materials to attract audiences to the seven films he made with Wales.

In 1938, Silver King starred as Silver, The Lone Ranger’s horse, in a fifteen-episode serial. Directed by John English and William Whitney, the series was filmed in the famous Alabama Hills in Lone Pine, California, the setting of many B Westerns. Silver King, then likely in his twenties, received top billing, a testament to his enduring star power. Since the existence of Silver as The Lone Ranger’s horse has been traced back to 1938, it is even possible that he was modeled on the great Silver King.

Silver King traveled in a customized trailer emblazoned with his name.

Other Cowboy Duos

Many more real cowboys rode the silent celluloid range. Another veteran of Wild West shows to achieve stardom was Jack Hoxie, whose lesser known actor brother Al sometimes doubled him. A fan of the Appaloosa breed, Jack Hoxie became popular along with his most famous mount, Scout, a handsome leopard Appaloosa with black spots.

Trick riders Art Acord and Hoot Gibson performed with Dick Stanley’s Congress of Rough Riders as well as the Miller Brothers 101 before they rode into Hollywood from the rodeo circuit.

Art Acord kept rodeoing after he began his film career in 1909 and was crowned World Champion Steer Bulldogger in the 1912 Pendleton, Oregon, Round-Up. During his successful career in silent films, Acord was paired with several different horses. He rode Buddy, Black Beauty, Darkie, and Star, but Raven was his favorite. In the The Circus Cyclone, 1925, Raven played a pivotal role as the horse of a comely circus performer named Doraldina (Nancy Deaver). When she resists the crude advances of the circus owner (Steve Brant), a former boxer, he beats her horse. Cowboy Jack Manning (Acord) comes to the rescue and wins the horse in a boxing match against the circus owner.

As Jack Manning, Art Acord protects Raven from the pugilist circus owner, Steve Brant (Albert J. Smith) in The Circus Cyclone, 1925.

Hoot Gibson, an expert at Roman riding (the art of standing upright on the backs of two horses working in tandem, which despite its name has no link to ancient Rome), won the Allowed-Around Champion title at Pendleton the same year Art Acord won his award. Gibson began his film career doubling silent star Harry Carey. His daring stunt work eventually landed him his first starring role in a 1919 “two-reeler” series. (The approximately twenty- to thirty-minute “two reelers” consisted of two short reels of film.)

In King of the Rodeo (1929), Gibson demonstrates his rodeo expertise. For most of the movie, the affable Gibson rides his palomino, Goldie. Gibson rode several other horses during his career, including Midnight, Starlight, and Mutt, but he was most often associated with Goldie.

Hoot Gibson and Goldie with the cast and crew of the 1925 Universal Pictures production The Saddle Hawk on the grounds of what is now Universal City.

African-American rodeo star Bill Pickett was promoted as the “World’s Colored Champion” in the Norman Film Manufacturing Company’s 1923 production of The BullDogger. Bulldogs were often used by cattle ranchers to help herd unruly steers. In 1903, Pickett had witnessed such a bulldog force a steer into submission by leaping at its head and biting its lip. By imitating the dog’s technique, he developed the rodeo sport of bulldogging: galloping after a steer, leaping onto its neck, wrestling it to the ground, and biting its lip. In 1907, Pickett joined the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West Show and, with his courageous steed Spradley, popularized the daredevil sport. (The lip-biting flourish has since been dropped from the rodeo event.) Pickett’s sensational theatrics led to his starring film role, which according to a press release included “fancy and trick riding by black cowboys and cowgirls.” Pickett made one more film for Norman, a Western titled The Crimson Skull, in 1923. Featuring the heroics of thirty black cowboys, the film celebrated an often overlooked segment of America’s Western history.

For a brief time, rodeo champion Yakima Canutt, who won the Pendleton All-Around title in 1917, took a star turn and made a few pictures with a horse called Boy. Canutt eventually gave up acting and concentrated on stunt riding, doubling many Western stars, including John Wayne. In the stunt business, Canutt is revered for pioneering the difficult maneuver of leaping from a galloping horse onto one of the leads of a team of carriage horses and working his way along the rigging of the running team to the vehicle. He perfected this stunt in Stagecoach (1939). For the spectacular sequence, he added shimmying along underneath the moving coach, getting shot by Wayne, and falling to his “death.” Eventually, Canutt became a stunt coordinator and second unit director, staging some of the greatest horse action of all time, including the thrilling chariot race in the 1959 blockbuster Ben Hur.

Yakima Canutt leaps from wagon seat to a team of galloping horses in one of the many spectacular stunts he performed for the movie Stagecoach (1939).

Yakima Canutt and his horse Boy, circa 1925, in a rare portrait on the set of one of the low-budget oaters they made for Ben Wilson’s Goodwill Pictures.

Rarely seen posing, famed stuntman Yakima Canutt inscribed this publicity shot from his acting days with Boy to pioneering Western director Hobart Bosworth, who happened to be a direct descendant of Miles Standish and John and Priscilla Alden.

And One Little Cowgirl

Even child star Baby Peggy (Diana Serra Cary) got into the act. Baby Peggy’s wildly successful films parodied popular films of the day. In several 1921 two-reel Western comedies, the three-year-old superstar was paired with a miniature jet black horse named Tim. Taught to ride by her stuntman father, the cowboy Jack Montgomery, Baby Peggy mustered all her strength to try to control the obstreperous little horse. Although he was only 36 inches tall at the withers, or 9 hands as horses are measured, Tim was a pistol. “He was a difficult horse,” says Diana, reminiscing about her Baby Peggy days with Tim. “He was always cow-kicking and pinning his ears.” He also ran away with her one day when she and her father were out for their Sunday ride on the bridle path that used to run along Sunset Boulevard from the beach to Hollywood. Father and daughter were quite a sight as Jack, in a white Stetson hat, was mounted on his 17-hand gray horse, White Man, and Diana was astride tiny Tim. A passing trolley car startled Tim and he bolted. Jack could easily have reached down and swept his daughter from Tim’s back, but he wanted her to learn to control him. Listening to her father as he shouted instructions at her, Diana managed to turn the runaway Tim on to a side street where she “finally planted him on his tail almost in the laps of a couple who were reading their Sunday paper on the ivy-covered porch of their bungalow.” After that episode, she says that Tim turned into a very honest horse.

Silent star Baby Peggy (Diana Serra Cary) parodied the cowboy-horse partnership on her miniature horse, Tim, in Peg O’ the Mounties, 1924.

Future Legends Get a Leg Up

Marion Michael Morrison was no stranger to the saddle. He grew up in the California desert town of Lancaster and rode an old mare named Jenny to school and back, a 10-mile round trip. “Riding a horse always came as naturally to me as breathing,” he once said, “and I loved that mare more than anything in the world.” Young Morrison, nicknamed Duke, was heartbroken when Jenny had to be put down. He was destined, however, to forge bonds with quite a few more horses in his life as an actor.

Duke Morrison won a football scholarship to USC but, like so many other young men, was drawn to Hollywood. Inspired by his idol, silent Western star Harry Carey, Morrison had a hankering to be a screen cowboy. He worked as a prop man and appeared in a number of films as a bit player until director Raoul Walsh gave him a break in the 1930 Western The Big Trail. Walsh reportedly also gave Duke Morrison a new name: John Wayne.

The Big Trail was not a big success, but it started Wayne on his own trail to superstardom. In a series of films for Warner Brothers, he was paired with a white horse named Duke (after Wayne’s own nickname). One of these movies, Ride Him, Cowboy (1932), is credited with making Wayne a star. Wayne shared billing with Duke, “his Devil Horse,” but the handsome former parade horse, with a long flowing mane and tail, looked anything but devilish.

In later films, Duke (really several different white and light gray or cream horses) became the Wonder Horse. It’s amusing now to watch these old films and hear the actor talking to Duke as if to an intellectual equal, something Wayne later admitted he didn’t particularly like. In those early days of Westerns, however, there was nothing better for jump-starting an actor’s career than the right costar—a good horse.

Another screen legend, Gary Cooper, had his first starring role as “the Cowboy” in the 1927 silent Western Arizona Bound. An excellent horseman who spent part of his youth on a Montana ranch, Cooper performed most of his own stunts, including a transfer from a horse onto a fast-moving stagecoach. Later that year, he starred as the title character of Nevada aboard a bald-faced sorrel and appeared with a horse named Flash in The Last Outlaw. Variety Weekly raved about this last film: “Cooper does some good work, rides fast and flashy on his horse ‘Flash,’ and impresses with his gun totin’ generally.” Gary Cooper’s illustrious career was officially launched—with the help of Flash.

Gary Cooper deploys his cowboy charm on schoolmarm Mary Brian in 1929’s The Virginian.

the Duke relaxes with Duke, his handsome Ride Him, Cowboy costar.

Rex, “King of the Wild Horses”

Most of the early horse actors found fame as partners of cowboy stars. Not Rex, an amazing black stallion, who became a star in his own right. Billed as Rex the Wonder Horse, this beautiful Morgan had incredible screen presence and a genuine wildness that enthralled audiences.

Foaled in Texas in 1915, Rex was registered as Casey Jones. Reportedly abused as a colt, he was eventually sold to the Colorado Detention Home to be used as a breeding stallion. One day a student took Rex out for a ride and never returned. His body was found near a stream, and it appeared that he had been dragged to death. Perhaps he fell and caught his foot in the stirrup, panicking Rex. Whatever happened, the stallion was branded a killer and sentenced to solitary confinement for two years.

Meanwhile, producer Hal Roach was preparing a new film in 1923, The King of the Wild Horses. He was looking for a fresh black stallion to play the lead and recruited Chick Morrison, who looked after Roach’s polo ponies, to find the star. Morrison and Jack “Swede” Lindell, considered the most gifted horse trainer in Hollywood at the time, scouted prospects in several western states. The men heard about the “killer stallion” at the Detention Home near Golden, Colorado. They decided to take a chance and went to see Rex. Morrison and Lindell were impressed with the stallion’s charisma. They worked with him at the Detention Home for a week and schooled him at liberty, without a bridle or ropes connecting the horse to the trainers. At the end of the week, they staged a demonstration for the astonished wardens. Standing at opposite ends of the town’s Main Street, Morrison and Lindell called Rex back and forth between them, using only their voices and whip cues. The stallion’s talent confirmed, Morrison and Lindell bought Rex for $150 and brought him to Tinseltown, where he was stabled at the barn of Clarence “Fat” Jones, one of the largest suppliers of movie horses.

Rex, the glorious equine matinee idol, displaying the stare that unnerved his human costars and won him millions of fans.

Despite his ability to work at liberty, Rex never became a docile actor. He was famous for quitting when pressed too hard for obedience and once ran 17 miles from the set on a Nevada location. It was this untamed aura that attracted audiences, making it worthwhile for the studios to work with the difficult horse. Rex made his debut in King of the Wild Horses, the film that gave him his nickname, and became an instant hit. Hal Roach Studios quickly capitalized on Rex’s appeal with Black Cyclone (1925) and The Devil Horse (1926). In all these films, he was perfectly typecast as a wild stallion. Hank Potts, a pioneer movie-horse handler, once said there was “an unusual and arresting gleam in Rex’s eyes, like the untamable stare of an eagle.” On one location, Navajo on the film said that Rex had a devil imprisoned in him. Some even wore amulets against his “evil eye.”

Oddly, Rex was infuriated by spitting, perhaps as a result of being so taunted at the Detention Home. Whatever the origin of this bizarre quirk, Lindell exploited it to incite the horse’s on-screen wrath. Standing just off camera, Lindell only had to spit, and Rex would charge forward, eyes wild and teeth bared.

The black stallion Rex strikes a regal pose in his debut film, The King of the Wild Horses (1924). In his best penmanship, Rex has inscribed this photo to early cinematographer and special- effects man Ernie Crockett.

Since most actors refused to work with Rex, his double, a quiet gelding named Brownie, was used in close-up scenes. Only the fearless former rodeo star, actor, and topnotch stuntman Yakima Canutt would work “up close and personal” with the stallion. Canutt costarred with Rex in The Devil Horse and had a close encounter with his wild side. In one scene, Rex had to run to Canutt’s character during an Indian battle. He had performed the liberty work beautifully for several takes, but Canutt noticed he was getting mad. He warned the director, Fred Jackman, that the horse needed a break. Jackman pressed for one more take—and Rex snapped. He charged Canutt, baring his teeth. “I tried to duck,” Canutt remembered in his autobiography, “but his upper teeth hit my left jaw and his lower teeth got my neck. I was knocked to the ground, and he reared above me, striking down with his powerful front hooves.” Canutt managed to roll away and kicked Rex on the nose. Still the horse came after him even when Lindell tried to call him off. “I finally rolled over a bank and escaped,” wrote Canutt.

Rex’s frequent costar was a pinto stallion, Marky. Sometimes he was used as a shill, to incite Rex to fury with an off-screen whinny. Marky had some hair-raising on-screen tussles with Rex, carefully orchestrated by Lindell, who made sure neither stallion was injured no matter how vicious the fight appeared. Their hooves were shod in soft rubber shoes to soften kicks, and their teeth were wrapped in gauze to prevent serious bites. Fake blood added to the realism of the fight scenes, which were acted for keeps by both stallions.

Behind the back of an oblivious Native American chief, Rex’s nemesis, the pinto Marky, menaces his off-screen rival in The Devil Horse (1926).

In early 1927, Rex was sold to Universal Pictures. There he continued his career, appearing in several films with Jack Perrin, an appealing cowboy actor. One such film was Guardians of the Wild, released in 1928. Perrin plays Jerry, a forest ranger who talks to his gorgeous light gray mare, Starlight, the actor’s frequent costar. As bright as she is beautiful, Starlight, of course, understands every word. Playing a sympathetic character for a change, Rex is depicted as smarter than Jerry and expends a considerable amount of energy trying to communicate with him.

Critics loved Rex, as is obvious in this 1928 review of Guardians of the Wild from Photoplay magazine: “Rex, the ‘Wonder Horse,’ is the star; but you see little of him. He’s buried under a pile of screaming heroine, half-witted hero, wronged father, and leering villain. Too bad a horse can’t choose his own stories!”

In another of Rex’s films, Wild Beauty (1927), the stallion costars with a French Thoroughbred mare named Valerie. The film features Rex at his wildest, killing a mountain lion, battling cowhands who have roped him, tearing into a rival stallion with a vengeance, and galloping at breakneck speed to accomplish his varied goals in the film. His performance is truly stunning.

Rex never outgrew his wildness. In fact, during the filming of Smoky in 1933, he charged an actor and knocked him to the ground, as scripted. What followed was pure improvisation by Rex, who began tearing the man’s clothes off with his teeth. The director cut the frightening scene from the film.

Rex is credited in nineteen films, but he played anonymously in countless others as an incorrigible stallion. His career continued into the talkies era, and in 1935 at age twenty, he costarred with the German Shepherd Rin Tin Tin Jr. in a twelve-part Mascot serial, The Adventures of Rex and Rinty. Rex made his final film in the late 1930s. He eventually retired to the ranch of Lee Doyle in Flagstaff, Arizona, where he was turned out with a band of mares. Although Rex sired a number of foals, none became a movie star. Truly one of a kind, Rex passed away sometime in the early 1940s.