Читать книгу Hollywood Hoofbeats - Audrey Pavia - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

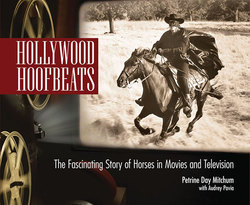

Оглавление3. Horse Heroes and Singing Cowboys

“Back in the saddle again, back where a friend is a friend…”

—Gene Autry and Ray Whitley, “Back in the Saddle Again”

Pardner and friends are serenaded by Monte Hale.

The advent of sound opened up whole new vistas on the celluloid range. Actors could be heard delivering their lines at last, and sound effects provided extra realism. For Westerns, this meant that for the first time, smacking fists, gunfire, and thundering hooves rattled speakers in movie houses across America. It also meant the birth of a new kind of Western hero: the singing cowboy. Tough enough to roust out the vilest varmint, the singing cowboy was also clean living and honest to a fault, with a smile and a song always at the ready. More than one of these new heroes sang his way into the hearts of moviegoers. The two most famous were Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. Just as celebrated were their horses, Champion and Trigger.

Gene Autry and the original Champion, along with their costar Buck, grace a lobby card for their movie Melody Trail (1935).

The Horse Opera

Cowboy music was already extremely popular with radio audiences so it’s no wonder that the first sound Western, In Old Arizona (1929), was also a musical. Warner Baxter won an Academy Award for his performance as the Cisco Kid. Both he and his costar, Dorothy Burgess, sang as did members of the cavalry. A microphone strategically hidden in some sagebrush captured the exciting sounds of galloping horses for the first time in movie history. The immense success of this Best Picture-nominated venture convinced filmmakers that cowboys and music were a marriage made for box-office heaven, and the horse opera was born.

The singing cowboy’s boots are planted in practical tradition. Cowboys driving cattle from Texas to northern stockyards learned that nervous steers could be comforted by song. Yearning for amusement after dusty days on the trail, cowboys also sang to entertain one another. While no record of these early singing cowboys’ efforts exists, they sparked an enduring tradition. Even now, many country music stars dress as cowboys and cowgirls, embracing the imagery of the Old West that has come to symbolize all-American qualities of integrity and freedom.

Tom Mix hired live cowboy singers to entertain audiences between showings of his silent films but never attempted to warble himself. Western star Ken Maynard, however, had “long had a hankerin’” to sing, and in his first all-sound feature, Kettle Creek (1930), he not only performed some of his most spectacular stunts with Tarzan but also worked in some songs. He repeated the formula in a few more films for Universal. Although Maynard enjoyed a brief recording career with Columbia Gramophone, the cowboy star had a raspy, nasal singing voice that limited his appeal. Undaunted, he bought the film rights to a popular ballad about an incorrigible horse, “The Strawberry Roan,” and sang the title song in the 1933 movie of the same name. Maynard believed the singing cowboy was the next big thing, and Mascot Pictures chief Nat Levine agreed. In 1934, Levine produced In Old Santa Fe, which blended Wild West action and cowboy music on a modern dude ranch. Ken Maynard and Tarzan received top billing, but a young WLS radio star named Gene Autry, the “Cowboy Idol of the Air,” stole the singing thunder of his own long-time idol Maynard, whose poor singing had to be dubbed in the movie. Maynard and Tarzan were already fading into the sunset as Autry began his meteoric rise.

America’s Cowboy and the World’s Wonder Horse

“Back in the Saddle Again,” a catchy song about the pleasures of riding the range, became the first famous singing cowboy’s theme song. In Gene Autry’s case, the saddle was usually aboard one of a series of blaze-faced sorrel horses, all named Champion, who costarred with Autry in more than eighty films.

The Yodeling Cowboy

Born in 1907, a few miles outside the small town of Tioga, Texas, Gene Autry grew up around horses since his father, Delbert Autry, was a horse trader and livestock dealer. Blessed with a beautiful singing voice, Gene Autry was recruited for the choir in his Baptist minister grandfather’s church when he was just five years old. A little later, his mother taught him to play the guitar on a mail-order instrument. Young Autry was too practical, however, to consider music more than a hobby. Determined to avoid the financial insecurity that plagued his father’s life, he pursued more sensible ways to support himself. In 1924, the teenaged Autry was working as a telegrapher. On slow days, he would amuse himself by playing the guitar and singing. On one such day, legendary western entertainer Will Rogers came in to send a telegram. After hearing the young man sing, Rogers encouraged him to try his luck in show business. Despite his previous concerns, Autry decided to take the advice and eventually landed a job singing on Tulsa station KVOO and became Oklahoma’s Yodeling Cowboy.

Autry initially found success as a radio personality, songwriter, and recording artist. By the end of 1931, he was a star on the network National Barn Dance and had his own radio program, Conqueror Record Time. His first hit, “That Silver Haired Daddy of Mine,” became the first million-selling gold record. Deservedly known for his business acumen, Autry realized the wide commercial appeal of a clean-living cowboy and honed his image accordingly. He came to the attention of Mascot’s Nat Levine, who cast him in In Old Santa Fe. Billed as the “World’s Greatest Singing Cowboy,” Autry sang two songs in the film and had a few spoken lines. Despite his greenhorn status as an actor, moviegoers responded positively to Autry and his smooth, melodious voice.

Gene Autry sings from atop the original Champion, who is easily distinguishable from his successors by his three white stockings.

The Phantom Empire

Mascot subsequently signed Autry to star in a twelve-chapter serial, Phantom Empire, a kitschy combination of science fiction and Western genres that showcased the actor’s singing. To bring Autry’s riding ability up to snuff, the studio paid for lessons with former rodeo champion and stuntman Yakima Canutt.

In the Phantom Empire series, Gene Autry played himself as the cowboy star of the Radio Ranch radio program who gets involved with a subterranean colony of technologically advanced aliens, the Muranians. The series also featured a terrific young trick rider, Betsy King Ross. In the series, the Muranians have a mounted army that surfaces to pursue their foes. Dubbed the Thunder Riders by Betsy and her serial brother, Frankie Darro, the alien cavalry prompts the kids to start their own club of junior Thunder Riders. It’s quite something to see the caped and silver-helmeted Muranians galloping along the prairie, with a gaggle of kid mock aliens wearing customized silver buckets on their heads tearing along on their own horses. Autry’s mount in the series varied, but sometimes his horse is a blaze-faced sorrel with three stockings, sometimes one with four. Whether any of these horses went on to become the original Champion is not certain, but clearly Autry’s preference for the color combination was evolving.

Original Champion—Wonder Horse of the West

The success of Phantom Empire led to Gene Autry’s first feature-length star vehicle, Tumbling Tumbleweeds (1935), which also introduced Champion. Although uncredited, the original Champion is easy to spot because of his three white stockings and distinctive T-shaped blaze. A 1939 promotional spot showing Autry putting Champion through his paces revealed that the gelding also had a large patch of white on his belly, visible only when he rolled on his back.

There has been much confusion about the number of Champions, their markings, and their origins. Autry, probably hoping to perpetuate the myth of a single Champion among his fans, was not particularly helpful when questioned on the subject. In one interview, he stated that the original Champion had come from Oklahoma and in another that he had acquired Champion from the Hudkins Brothers Stables, a company that provided horses for Autry’s films. It has been widely accepted that the Hudkins brothers owned the original Champion and perhaps he originally came from Oklahoma. Regardless, the dark sorrel gelding was chosen because he photographed well. With three white stockings and one dark right foreleg, he can be easily distinguished from subsequent Champions, who all had four white stockings of varying height. The T-shaped blaze starting high on his forehead and extending over his muzzle further distinguishes the original Champion.

Autry and producer Armand Schaffer reportedly chose the name Champion, deciding that “Champion” reflected “the best of everything.” It was a fitting name for the clean living hero who championed a strict code of ethics known as the Cowboy Code. Champion first received billing in 1935’s Melody Trail. As his partnership with Autry solidified, the gelding began to be billed as the “Wonder Horse of the West.” Trained by Tracy Layne, he could untie knots, roll over and play dead, bow, nod his head for yes and shake it for no, and come to Autry’s whistle. Wearing his signature bridle featuring bit shanks in the shape of pistols, he carried Autry safely through many adventures. Sometimes he merely had to stroll along the prairie looking sharp while Autry sold a song from his saddle. That might sound like easy work, but it takes a special horse to mosey along carrying a singing cowboy while being photographed by a motion-picture crew and its attendant paraphernalia. Sometimes such scenes were photographed on a soundstage with the horse on a treadmill and the scenery projected in the background. On other occasions, Autry and Champion are clearly riding through the sagebrush outdoors.

The original Champion starred with Autry in all his Mascot and Republic Studios pictures until the actor’s screen hiatus during World War II. His last picture was The Bells of Capistrano (1942). It has been written that in 1943 Champion, approximately seventeen years old, died of an apparent heart attack on Autry’s Melody Ranch, while his master was in the army. Johnny Agee, who was employed by Autry to train and care for his horses, reportedly buried Champion. An obituary notice in the January 26, 1947, edition of the New York Times tells a different story, reporting that the original Champion was retired in 1943 and died on January 25, 1947, at age seventeen. Perhaps the former story was concocted to romanticize Autry’s loss of his original horse, who may well have been retired due to lameness—a not uncommon side effect of toiling in Westerns. Even though he had multiple stunt doubles, Champion did do quite a bit of galloping over hard ground in his early movies, which over time damages the tissues and bones of a horse’s legs.

Champion Jr. and Little Champ

Returning to films in 1946’s Sioux City Sue, Autry rode a new horse, who would be billed as Champion in Autry’s first three postwar films. In 1947’s Saddle Pals and Robin Hood of Texas, the same horse is billed as Champion Jr., but when The Last Round Up was released later that same year, the “Jr.” had been dropped and the mythical “Champion” returned.

Champion Jr., the second screen Champion, was a high-spirited sorrel stallion—who was eventually gelded—with a flaxen mane and tail and four high white stockings. He had a narrower blaze than his predecessor, and it ended in a snip on his nose. Remarkably, he also had a white patch on his belly. He was a show horse originally called Boots and owned by Charles Auten of Ada, Oklahoma. Having heard that Autry was looking for a new Champion, Auten supposedly hauled the four-year-old Boots to Fort Worth, Texas, when Autry was appearing at a rodeo there. The actor reportedly bought the horse for $2,500, even though he later claimed he had never paid more than $1,500 for a horse. The name Boots certainly seems an apt one for Champion Jr., as his flashy stockings extended well up to his knees.

Champion Jr. became known only as Champion, and his status was elevated from “Wonder Horse of the West” to “World’s Wonder Horse” when Autry moved from Republic Pictures to Columbia Studios. More highly trained than the original Champion, he could dance as well as perform an impressive array of tricks. He made some personal appearances with Autry and appeared with him at Madison Square Garden in 1946.

Starring as a wild stallion, Champion (Jr.) showed off his talent in a remake of the Ken Maynard vehicle The Strawberry Roan (1948), Autry’s first color film. The film also marked the debut of Little Champ, a foal supposed to be Champion’s son. Little Champ grew up to become a well-trained trick pony, featured in two more films, Beyond the Purple Hills (1950) and The Old West (1952). He also appeared at Gene Autry’s Madison Square Garden rodeo in 1948 and traveled with the 1949 national tour of “The Gene Autry Show.” A junior version of the Champions, he, too, was a blaze-faced sorrel with four stockings. There’s no record of how long this little crowd-pleaser lived, but based on the great care Autry took of all his horses, Little Champ doubtlessly had a good life.

As for Champion Jr., he and another Champion named Wag were put to sleep at Melody Ranch on December 29, 1969, “due to old age,” according to a handwritten note found in Autry’s personal archives.

The four high white stockings of Champion Jr. earned him the nickname Boots.

The Touring Champions

Autry made quite a few appearances with at least three more Champions. The touring Champions were also sorrel geldings with white blazes and four stockings, instead of three. All were highly trained trick horses.

One of these was known as the Lindy Champion because he was born in 1927 on the day of Charles Lindberg’s first flight over the Atlantic. Originally from Nashville, Lindy was a registered Tennessee Walking Horse trained by Johnny Agee. He had also been used by Tom Mix in live appearances. Distinguished by an oval-topped blaze and a black dot on his nose (sometimes powdered or bleached), he made aviation history of his own when he became the first horse to take a transcontinental flight. In September 1940, he flew in a customized stall aboard a TWA plane from Burbank, California, to New York City for the opening of the Gene Autry rodeo show at Madison Square Garden. It is not known how long the Lindy Champion lived, but since he was born in 1927 and was still working at thirteen, he undoubtedly had a long life.

The horse most commonly known to insiders as the Touring Champion appeared with Autry in the late 1940s and the 1950s at rodeos and stage shows, including Madison Square Garden in 1947. He joined Autry on a publicity tour of England in 1953 and accompanied him into the Savoy Hotel. Widely photographed, this Champion is also the horse immortalized by his hoofprints next to Gene Autry’s handprints at the Chinese Theater in Hollywood. He can be identified by his medium-wide blaze, which veers to the right side of his forehead. It’s possible that the “Touring Champion” was the one called Wag who, like Boots, was euthanized in 1969. The final Touring Champion, and Autry’s last horse to be honored by the name, had a crooked blaze that feathered into his roan color on the left side of his face. Yet another sorrel with four white stockings, he was a stockier gelding than his predecessors. He never worked in films but accompanied Autry on personal appearances from the late 1950s until 1960. He also joined the star on the Merv Griffin and Ed Sullivan television shows. This final Champion, called Champion III by Autry insiders, died at Melody Ranch in 1990. He was forty-one.

Gene Autry, of course, fulfilled his youthful dream of financial stability and implemented his business skills to build a media empire. Returning to his roots in broadcasting, Autry launched a solo career for his mythical horse with The Adventures of Champion radio serial. Lasting one season, from 1949 to 1950, the show aired on the Mutual Broadcasting system and featured celebrity guest stars.

Among the first entertainers to understand the power of television, Autry starred in his own production, The Gene Autry Show. Yet another Champion starred with Gene in ninety-one episodes from 1950 to 1955. Trained by Glenn Randall, this horse was a light sorrel gelding with a wide blaze extending over his nose and lower lip. A lack of pigmentation around his eyes was usually covered with make-up. In 1949, at the outset of the horse’s career, as a publicity stunt, Autry took out a $25,000 insurance policy naming this Champion as beneficiary. The same Champion inspired a comic book series, Gene Autry’s Champion. When The Gene Autry Show left the air, Champion remained on TV without Autry in a spin-off of the comic-book series. Named after the radio program, The Adventures of Champion aired on CBS from September 1955 to March 1956, for twenty-six episodes. This Champion had replaced Champion Jr. as Autry’s movie horse in the 1950s, so he appeared in Autry’s final films as well. Gene Autry passed away on October 2, 1998, just a few days after his ninety-first birthday. The great singing cowboy and his iconic horse Champion have been immortalized by a gorgeous life-size bronze sculpture aptly titled “Back in the Saddle,” which graces the plaza of the Autry National Center in Griffith Park in Los Angeles. Autry’s last Champion, Champion III, was the life model for the sculpture by De L’Esprie.

TV Champion and Little Champ flank Gene Autry in this photo.

Lindy Champion and autry prepare for takeoff in September 1940 with TWA stewardess Esther Benefiel, who fed Champ carrots at takeoff and landing to protect his eardrums from pressure changes.

Champion Jr. starred with Gene Autry in his favorite movie, Sioux City Sue, but the Touring Champion, with his veering blaze, posed for this lobby card.

The Touring Champion looks a bit uncertain about becoming the second horse (after Tom Mix’s Tony) to leave his mark in cement at Grauman’s Chinese Theater. Trainer Johnny Agee (in plaid shirt) holds the reins while Gene washes his hoof with the help of theater owner Sid Grauman, on the right. The date was December 23, 1949.

The King of the Cowboys and the Smartest Horse in Movies

Gene Autry and Champion blazed the trail for their chief rivals, Roy Rogers and Trigger. The cowboy with twinkling eyes and his beautiful golden palomino stallion still hold a special place in the hearts of many movie fans. Some are lucky enough to have seen the spectacular duo in one of their many personal appearances, as Rogers, bedecked in rhinestone-fringed splendor, galloped into a stadium on his shimmering stallion. The dazzling sight was pure magic.

Gene is seen here with his last Champion, Champion III.

Leonard Slye and the Sons of the Pioneers

Born Leonard Frank Slye in a Cincinnati tenement on November 5, 1911, Rogers overcame his humble beginnings to pursue his dream of a career in show business. Developing his natural musical talents, he eventually headed for Hollywood, where he formed the Pioneer Trio, which landed a KFWB radio spot in 1933. The Pioneer Trio evolved into the Sons of the Pioneers, one of the most successful cowboy groups in history.

The Sons of the Pioneers appeared in several films, including Gene Autry’s Tumbling Tumbleweeds. But Leonard Slye had his sights set on solo stardom. In 1937, Republic Pictures was holding auditions for singing cowboys. Without an appointment, Slye pulled on his white Stetson and sallied past the Republic gate guard with a group of studio employees. A fan of the Sons of the Pioneers, producer Sol Siegel invited the singer to audition, and on October 13, 1937, Slye signed a seven-year contract with Republic at $75 a week. His name was promptly changed to Dick Weston.

Dick Weston languished in bit parts until Autry went on strike in 1938 just before the start of his new picture Under Western Stars. Slye/Weston was tapped to replace the star. After the producers decided he needed a catchier name, Slye picked the surname Rogers in tribute to his hero, Will Rogers—ironically the man who had kick-started Autry’s career. Even though the actor didn’t particularly like the name, Roy was chosen because of its pleasing alliteration with Rogers.

Quick on the Trigger

Roy Rogers shrewdly figured that if he partnered with a unique horse, he would be harder to replace should he fall out of favor with Republic. He tried out several horses owned by the Hudkins Brothers Stable and struck gold with Golden Cloud, a registered palomino, half-Thoroughbred stallion with a wide blaze and one left hind sock. His golden color was highlighted by an exceptionally long snowy mane and forelock. The Hudkins brothers had acquired the horse from the ranch of Ray “Crash” Corrigan, another cowboy star. Golden Cloud’s sire was a Mexican racehorse, and his dam was what Rogers called a “cold-blooded” palomino, most likely a Quarter Horse mix. At only three years old, he had already debuted as Olivia de Havilland’s mount in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). The stallion’s matinee idol’s looks and his amazingly tractable temperament marked him for stardom.

Roy Rogers once said, “I got on [the horse that was to become] Trigger and rode him down the street and back. I never looked at the rest of them. I said, ‘This is it. This is the color I want. He feels like the horse I want, and he’s got a good rein on him.’ So I took Trigger and started my first picture.”

According to Cheryl Rogers-Barnett, Roy’s eldest daughter, “Dad always told me there was a genuine connection between the two of them, right from the first time he sat in the saddle. Dad had a gift for handling most animals, but he said there was some sort of instant communication between him and Trigger. In Dad’s case, it was love at first sight.”

Golden Cloud became Trigger when Rogers and his comic costar Smiley Burnette were brainstorming to find a more fitting name for a cowboy’s horse. “The name came up when we were getting ready to do the first picture,” Rogers once explained. “I believe it was actually Smiley who said, ‘As fast and as quick as the horse is, you ought to call him Trigger. You know, quick-on-the-trigger.’ I said, ‘That’s a good name.’ And I just named him Trigger.” The naming scene is recreated in My Pal Trigger (1946), which depicts the fictionalized birth of the stallion.

Roy and Trigger are hellbent for justice in 1951’s South of Caliente.

Costarring with Rogers in Under Western Stars (1938), Trigger, who had just turned four, was indelibly linked to the actor’s success. Realizing Trigger’s long-term value, Rogers arranged in 1938 to purchase the palomino from the Hudkins brothers for $2,500. It was a huge sum for Rogers on his meager salary, but Ace Hudkins agreed to let him make payments. It took several years before Rogers owned Trigger completely, but he never doubted his investment.

Rogers put Trigger in training with Glenn Randall, who schooled him at liberty and taught him some basic tricks, including how to rear. The stallion had tremendous strength and could hold a spectacular rear far longer than most horses. He also had great stamina and carried Rogers through many chase scenes. In one movie, Rogers and Trigger jumped a series of 50-gallon drums that rolled off the back of a truck they were chasing. Although unrehearsed, Trigger negotiated the jumps in one take. Billed as the “Smartest Horse in Movies,” he was easily the handsomest. Whether galloping pell-mell with his beautiful long mane flying in the wind or just standing by waiting for action, he was always a magnificent sight.

Trigger performing his trademark rear as trained by Glenn Randall, with cool-as-a-cucumber Roy Rogers resplendent in eye-catching fringed duds designed by Nudie, the famed Cowboy Couturiere, striking the iconic pose that captured the imaginations of millions of wanna-be cowboys and cowgirls.

Billed as the “King of the Cowboys,” Rogers was an excellent horseman. He did running mounts and dismounts on Trigger, who took it all in stride. Like most star horses, Trigger had doubles for dangerous stunts and rough-riding long shots. Contrary to rumors that Rogers owned many Trigger doubles, these horses were rentals from Hudkins or Glenn Randall. The good care Trigger received and his overall hardiness meant a horse that was never lame.

Rogers never gelded Trigger for fear of dulling his famous spark, yet never bred him either. According to Roy’s son Dusty Rogers, “Dad was afraid to breed because he was worried that Trigger might decide he liked breeding better than making movies.”

Like his famous predecessors, Fritz, Tony, and Champion, Trigger inspired movies that revolved around him. One of the most beloved was The Golden Stallion (1949). Trigger costarred with Roy Rogers in eighty-two movies between 1938 and 1953. Together they made the transition from film to television in December 1951 with the debut of The Roy Rogers Show. Trigger costarred in all one hundred episodes.

Rogers made the most of their fame. Roy Rogers’ and Trigger’s names and likenesses appeared on sixty-five products marketed in 1949. Roy Rogers’ Trigger, a Dell comic-book series based on the palomino’s escapades, sold millions of copies.

Trigger and Roy Rogers inspired scores of toys, such as this one.

Trigger worked well into his twenties and was eventually retired in 1957 at the Rogers’ ranch. After he died on July 3, 1964, at the age of thirty-three, Rogers had him mounted so the public could view Trigger at the Roy Rogers–Dale Evans Museum.

Little Trigger and Trigger Jr.

A couple of years after he acquired Trigger, Roy Rogers purchased another blaze-faced palomino stallion, known by insiders as Little Trigger (aka the Little Horse). A Morgan, this horse was smaller than Trigger (who then became known to the Rogers and Randall families as Old Trigger) and lighter in color. He had four white stockings. Seen on his own, however, Little Trigger looked enough like Old Trigger, with his handsome body and long flowing white locks, that he could pass for the original. He was presented to the public as simply Trigger. Just as Gene Autry always had one Champion, Roy Rogers perpetuated the myth of one Trigger and never mentioned Little Trigger in an interview.

Little Trigger was, according to both Rogers and Glenn Randall, truly the smartest horse in movies—or anywhere else for that matter. Highly intelligent, he learned quickly and retained more than a hundred cues for tricks and dances. Most astonishing of all, he was housebroken, a quality that allowed him to accompany Rogers on his many appearances in hospitals to visit sick children and into fancy hotels without worrying about an embarrassing mishap. He is the only celebrity horse of record who could accomplish this feat.

Little Trigger was also notoriously ornery and quick to show his displeasure by biting. According to Cheryl Rogers-Burnett, he didn’t like kids or women, which is ironic considering they composed much of his fan base. He did love the spotlight, however, and he knew that as long as he was performing in front of a crowd, Rogers wouldn’t discipline him. On one occasion, Little Trigger ruined a dramatic routine during which he and Rogers played dead. The stallion tried to sneak out of the stadium as the houselights were dimmed, leaving Rogers lying alone in the middle of the arena. The actor grabbed for Little Trigger’s reins and found his saddle horn. When the houselights came on, Little Trigger was gleefully galloping around the arena with Rogers hanging off the saddle. Furious, the actor intended to reprimand Little Trigger backstage and backed him into a corner. However, when Rogers approached the horse, the wily stallion started desperately going through his tricks, finally sitting down and bowing his head in prayer. Instead of punishing Little Trigger, Rogers cracked up laughing, along with the cowboys who had witnessed the amazing display.

Little Trigger doubled Trigger in dancing sequences in Don’t Fence Me In (1945). He also masqueraded as Trigger in the 1952 musical comedy Son of Paleface, starring Rogers, Bob Hope, and Jane Russell. He danced and performed many tricks, including untying ropes, running up a staircase, and sharing a bed with Hope, fighting over the covers. “Trigger” stole the show and won a PATSY, the American Humane Association’s version of the Academy Award, for his work.

Rogers and Little Trigger toured the country regularly, but their most famous appearance—and most notorious publicity stunt—took place in New York City during a 1944 Madison Square Garden engagement. Rogers led the stallion into the lobby of the Hotel Astor and offered him a pencil. Holding the pencil in his teeth, Little Trigger marked “X” on the guest register. Later, he attended a cocktail party honoring him in the hotel’s Grand Ballroom.

According to trainer Buford “Corky” Randall, son of Glenn Randall, Little Trigger lived well into his twenties and was humanely put down due to complications of old age. Rogers purchased a third palomino to understudy Little Trigger. Named Trigger Jr., he took over as Rogers’s personal appearance horse when Little Trigger was retired in the early 1950s. A flashy dark palomino with a blaze and four white stockings, Trigger Jr. was also trained by Glenn Randall. The new horse specialized in crowd-pleasing dance routines. Corky Randall showed Trigger Jr., a Tennessee Walking Horse, under his registered name of Golden Zephyr. Trigger Jr. appeared in a namesake film, Trigger Jr. (1950), alongside Trigger, who was six years his senior. Trigger Jr. was nine years old when Rogers purchased him. He died at twenty-eight and was also mounted and put on display at the Roy Rogers-Dale Evans Museum.

Trainer Corky Randall and Trigger Jr.—as Golden Zephyr—demonstrate the elegant Spanish walk at a horse show.

Jane Russell and Bob Hope share a meal with their costars Roy Rogers and Little Trigger on the set of 1952’s Son of Paleface.

Little Trigger and Glenn Randall play jump rope with Roy Rogers.

The Queen of the West and Buttermilk

In 1944, Rogers made his first picture with a dynamic singer and dancer named Dale Evans. The Cowboy and the Senorita proved to be a hit, and Rogers and Evans went on to make twenty-eight more features and one hundred television shows together. Along the way, they fell in love. Rogers proposed to Evans as they were about to ride into Madison Square Garden for a public appearance by asking, “What are you doing New Year’s Eve?” They married on December 31, 1947. The wife of the “King of the Cowboys” became known as the “Queen of the West.”

In her early Rogers films, such as 1945’s Bells of San Angelo, Evans rides a pinto. Rogers decided the Paint was too flashy, and Glenn Randall found a gentle palomino gelding called Pal for Evans. Rogers worried, though, that the horse’s color would draw attention away from Trigger. The quest began for a horse of just the right color.

Glenn Randall spotted an athletic little buckskin Quarter Horse named Soda on a Wyoming ranch. Soda had an extremely shaggy winter coat, but Randall could see his potential through the hair. He purchased the buckskin and hauled him back to California. When Soda shed his winter coat, his pretty conformation was revealed. Randall brought him to the location of one of Rogers and Evans’s movies and tied him next to Trigger. The two looked great together, with the buckskin’s black mane and tail contrasting nicely with Trigger’s opposite markings. Rogers approved, and Evans gave Soda a try. Quick and athletic, he was challenging to ride, but the “Queen of the West” was up to the task. She purchased Soda from Glenn Randall, who retrained him for the movies.

Soda needed a more theatrical name. On location in Lone Pine, California, the site of hundreds of Westerns, Evans and wrangler Buddy Sherwood were admiring the sunset. Sherwood remarked that the mottled milky clouds looked like “clabber.” Evans reportedly replied, “You mean buttermilk?” Thus she was inspired to rename the buckskin Buttermilk Sky.

Buttermilk Sky became known simply as Buttermilk, and Evans rode him in the remainder of Rogers’s films and the television series. He was not only smart and fast but also exceptionally quick off the mark. As soon as he heard “Action!” Buttermilk would spring forward, and Evans had to rein him back to let Trigger get ahead in films.

Buttermilk had a long, successful career supporting the superstar Trigger. Buttermilk also stands mounted at the Roy Rogers-Dale Evans Museum, alongside Trigger, Trigger Jr., and Roy and Dale’s German Shepherd, Bullet. Originally in Apple Valley, California, the museum is now in Branson, Missouri.

The Queen of the West, Dale Evans, and Buttermilk Sky display the charm that made them a perfect complement to Roy and Trigger.

Trainer Glenn Randall in a rare portrait aboard Soda before he became Buttermilk Sky.

The Second String

The immense success of Gene Autry and Champion and Roy Rogers and Trigger pushed many more singers into the saddle. Some of these “singing cowboys” were good horsemen but couldn’t sing—like John Wayne, whose voice was dubbed in his brief career as Singin’ Sandy Sanders. Others were decent crooners, but their cowboy personas were strictly Hollywood fantasy.

Popular star Eddie Dean could sing all right but he did not have a particular equine partner. Even though his various mounts were virtual unknowns, the studio still gave them cobilling: the mere fact that they were horses helped sell Dean’s films.

Broadway star Tex Ritter was tapped for the movies by Grand National Pictures in 1936 and quickly brushed up his horsemanship for his new career as a singing cowboy. Following the formula, Ritter was paired with White Flash, a studio invention played by different rental horses. It wasn’t until 1941 that Ritter purchased a permanent White Flash. Like his role models, the white horse with brown eyes went into training with Glenn Randall. Consequently, scenes were written for White Flash that enabled him to show off his tricks.

Crooner Monte Hale made a number of films for Republic during the 1940s. His equine partner was, appropriately, named Pardner. Despite an appealing singing voice and an affable persona as a gentleman cowboy, Hale never hit the big time. He maintained a sense of humor, however, and well into his eighties in 2005 when he received a star on Hollywood Boulevard’s Walk of Fame, was still passing out stickers commemorating the most ridiculous line of dialogue he ever had to utter, “Shoot low! They may be crawlin’.”

Herb Jeffries and Stardusk

One of the most unusual singing cowboys was jazz musician Herb Jeffries. Born in 1911 in Detroit, Jeffries inherited his light brown skin from his father’s Ethiopian ancestors. He learned to horseback ride on his grandfather’s farm and enjoyed watching Tom Mix and Buck Jones Westerns.

Jeffries began singing professionally as a teenager and toured with some of biggest names in jazz. While traveling through the South in 1934, Jeffries noticed that blacks-only movie theaters played all-white Westerns. Unfortunately, the trend started by the Norman Company and rodeo star Bill Pickett in the 1920s had not resulted in more Westerns about African-American cowboys.

One afternoon, in an alley behind a jazz club, Jeffries spotted some children playing cowboys and Indians. He noticed a little boy crying because his friends wouldn’t let him play. The child told Jeffries that he wanted to be Tom Mix, but his friends wouldn’t let him “because Tom Mix isn’t black.” Deeply touched, Jeffries determined that black children ought to have a cowboy hero who looked like them. He approached independent producer Judd Buell with an idea for a musical Western with a black hero. Buell agreed to finance such a film.

The challenge was finding a black actor who could sing and ride a horse. Jeffries wound up with the lead role by default. Because his skin was light brown, he applied dark makeup so black audiences would better relate to him. With the release of Harlem on the Prairie (1936), Jeffries—billed as Herbert Jeffrey—became the first black singing cowboy hero in a feature film. Of course, the hero had a four-legged friend. Jeffries chose a white horse named Stardusk. A hit with the kids, this pair made movie history.

Part Arabian, Stardusk had been bred on a ranch in Santa Ynez, California. When preparing for their first film together, Jeffries and Stardusk spent two weeks getting acquainted. By that time, Jeffries said, “We were pretty much in love with each other.”

After shooting wrapped on Harlem on the Prairie, Stardusk was returned to his owners in Santa Ynez. Jeffries, who was living in a Los Angeles boarding house, would visit regularly. As soon Jeffries arrived at the ranch, Stardusk would start whinnying for him. When producer Richard C. Kahn approached Jeffries with a deal for three more movies, the star made the purchase of Stardusk a condition of his contract. Together they made Two-Gun Man from Harlem in 1938 and two films in 1939, Harlem Rides the Range and The Bronze Buckaroo. Jeffries later moved to France and gave Stardusk back to his original owners, and the former thespian equine enjoyed the rest of his life in Santa Ynez.

Rex Allen and KoKo

An Arizona rancher’s son named Rex Allen would be the last of the singing cowboys. Like Autry and Rogers, the handsome blond Allen was signed by Republic Pictures after a career in radio. And like his predecessors, Allen knew he needed an extraordinary horse. Glenn Randall, meanwhile, had recently acquired KoKo, a stunning dark sorrel stallion with a flaxen mane and tail, from a female trick rider in Missouri. A Quarter/Morgan cross, KoKo had originally been purchased for Dale Evans but had proved too much horse for her.

The minute he laid eyes on KoKo, Allen fell in love with him. An accomplished rider, Allen found that the horse just needed a firm hand and some fine-tuning to get him ready for the movies. He bought KoKo from Glenn Randall in 1950 for $2,500. Randall continued to work with KoKo and Rex Allen during their short but successful career.

Allen’s first film, The Arizona Cowboy (1950), featured KoKo in an uncredited role, but in their next film, Hills of Oklahoma (1950), KoKo received billing. Dubbed the “Miracle Horse of the Movies,” he costarred with Allen in nineteen films for Republic, including Silver City Bonanza (1951), Rodeo King and the Senorita (1951), and their swan song, The Phantom Stallion (1954).

His unusual coloring destined KoKo to do nearly all of his own stunts. Although doubles were used for galloping long shots, they required considerable work to look anything like the stallion, even from far away. White horses were dyed a rich chocolate with vegetable coloring, with only a blaze, mane, tail, and stockings left white. Consequently, KoKo was worked hard, according to Allen, who once lamented, “I just had to run KoKo to death on nearly every film because we just couldn’t double him that close.”

KoKo only worked in movies for five years, from 1950 through 1954, during and after which time he also went on personal appearances with Allen. KoKo was retired in 1963 after foundering (the result of getting into a grain bin and gorging himself) and lived out the rest of his life at the Diamond X Ranch, Allen’s California spread. He died in 1968 at age twenty-eight. His remains are buried at the Cochise Visitor Center and Museum of the Southeast, in Wilcox, Arizona. His grave is marked with a plaque that reads: “KoKo, Rex Allen’s stallion costar in 30 motion pictures. Traveled over half million miles with Rex in U.S. and Canada. Billed as ‘The Most Beautiful Horse in the World.’ At rest here, ‘Belly High’ in the green grass of Horse Heaven.”

Rex Allen, the last of the singing cowboys, and Koko, showing off that famous Glen Randall trained rear.

White Flash shows off his Glen Randall-trained rear, with crooner Tex Ritter aboard.

Spotlight on Sidekicks

It gets lonely on the celluloid range, and a cowboy has only so many songs for his horse. He needs a human companion to help move the plot along, too, and in Westerns the bill was often filled by a sidekick. Offering comic relief, a helping hand, and a ready ear, the sidekick became a horse-opera staple. Two standout sidekicks, Smiley Burnette and Slim Pickens, rode alongside three of the most famous singing cowboys, on their colorful mounts Ring-Eyed Nellie and Dear John.

Smiley Burnette and Ring-Eyed Nellie

Lester “Smiley” Burnette had the distinction of working as a comic sidekick of Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. A musical prodigy, the twenty-two-year-old Burnette started his career with Autry as an accordion player on Gene Autry’s WLS radio show in 1933. Smiley accompanied Autry to Hollywood and appeared in his first feature film, In Old Santa Fe. Honing his screen persona as “Frog Millhouse,” the gangly, pudgy, sweet-faced Smiley used his deep bass voice to add comic punctuation to musical numbers. He appeared in fifty-four prewar Westerns with Autry, wearing a checkered shirt and trademark black Stetson with a pinned up brim. He rode a white horse with a black ring drawn around his (or her) left eye—so Burnette would remember to mount from the left. First known as Black-Eyed Nellie, the horse later became know as Ring-Eyed Nellie and finally just Ring Eye. The horses were studio rentals, but according to Smiley’s son, Stephen Burnette, his dad did have a favorite, one who would allow Smiley to lounge on his back reading the newspaper between takes.

When Gene Autry went into the service, Republic Pictures recruited Smiley and Ring Eye for several Roy Rogers films, beginning with Hearts of the Golden West (1942). When Autry returned to Hollywood, Burnette and Ring Eye resumed their partnership with him in 1951’s Whirlwind for Columbia Pictures. They worked in six more Columbia films during the 1950s. The name of Frog Millhouse belonged to Republic, however, so Burnette became Smiley once more. Ring Eye didn’t have to change his (or her) name.

Smiley Burnette had his own sidekick, played by Joseph Strauch Jr., who appeared with Burnette in five Autry films, beginning with Under Fiesta Stars (1941). Dressed in the same clownish outfit as Burnette, Strauch got laughs portraying Frog Millhouse’s younger brother, Tadpole. He was mounted on a Little Ring Eye, a white pony with a black circle painted around his eye.

Autry and the original Champion with their sidekicks, Smiley Burnette and Ring Eye and their sidekicks, Joseph Strauch Jr. and Little Ring Eye, as they appeared in Under Fiesta Stars.

Slim Pickens and Dear John

Rex Allen’s sidekick was Slim Pickens, a former rodeo clown known for his goofy charm and rubber-faced reactions. Born in Kingsburg, California, in 1919, Louis Bert Lindley Jr. acquired his nickname as a fifteen-year-old rodeo contestant. He was told his chances for winning were going to be “slim pickin’s.” As Slim Pickens, however, Lindley went on to reap many riches, along with a blue roan Appaloosa named Dear John.

Slim first spotted Dear John in 1954, in a Montana pasture. Although the young gelding had bucked off everyone who had tried to ride him, Slim saw something special in the Appaloosa. He purchased Dear John for $150 and took him to California to work in Rex Allen movies. Their first picture went smoothly, but on the second one, Dear John tested his new master, coming unglued. “After that,” Slim said in a 1973 interview, “it took more’n six months of us punishin’ each other before we came to an understandin’. After that there wasn’t anything that horse wouldn’t do that was in reason.”

Slim worked with Glenn Randall to teach Dear John a variety of tricks, including bucking on cue. Look closely at most bucking horses in a movie or at a rodeo, and you can see a “bucking strap” circling their bellies well behind the saddle. This piece of leather is so annoying to a horse that it drives him into a mad fit of bucking. Dear John was unusual in that he did not need a strap and was trained to buck with a combined rein and leg cue. Using this shtick to great comic effect, Slim would go galloping and bucking after Rex Allen and KoKo, bellowing, “Whoa John!”

Dear John was also taught to sit on his haunches like a dog, a trick he would perform on his own, long after he was retired to pasture. A powerful jumper, Dear John could clear teams of horses, wagons, and huge stone walls that scared Slim to confront. But he knew that if Dear John went at an obstacle, he could clear it. If the horse refused, it was because he knew he couldn’t make it, and Slim trusted Dear John’s decision. The two developed more than an understanding; they had an uncanny rapport and seemed to communicate telepathically.

By the end of his stint in Rex Allen films, Dear John had become so famous in Hollywood that Slim began getting calls for the horse. The actor refused to let anyone else ride Dear John and insisted on being hired to handle him as well.

Slim retired Dear John to a pasture owned by veterinarian Joe Hird, in Bishop, California, in 1964. He visited the horse frequently but had difficulty catching him as John was afraid he would have to go back to work. One day, however, when Slim and Rex Allen went to see Dear John, Slim was able to hop on his old pal bareback and cued him to buck. Dear John sent him flying, but Slim landed happy. Instead of running away as was his custom, Dear John rested his head on Slim’s shoulder affectionately. Several years later, Slim awoke in the middle of the night knowing his horse had gone. According to his wife, Maggie, he sat bolt upright in bed and said, “John’s dead.” A few days later, he got the confirmation call from Joe Hird, who had been unable to break the news at first. Dear John had passed away the night Slim received his last message. He was thirty years old.

You can almost hear Slim Pickens whoop for joy as Dear John puts some sky between them and the wagon in this publicity shot.

A little rough around the edges, Slim Pickens and Dear John are visual foils for the dapper Rex Allen and his stunning Koko in 1953’s Iron Mountain Trail.

Brave buckaroo Slim Pickens hangs on as Dear John does what he does best.