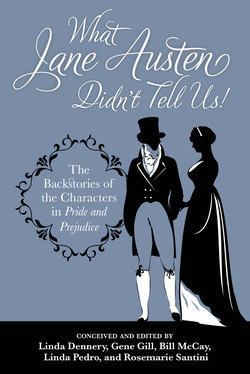

Читать книгу What Jane Austen Didn't Tell Us! - Austen Alliance - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Elizabeth Bennet by the Editors and Meg Levin

ОглавлениеThey are all silly and ignorant like other girls; but Lizzy has something more of quickness than her sisters.

—Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

Miss Elizabeth Bennet, her petticoats six inches deep in mud, pulled the wriggling piglet away from her eleven siblings busy nuzzling Bessie, Mr. Bennet’s prize Berkshire sow. Leaning forward, she reached for Bessie’s left ear. Surely, now she was almost three and a half, Nurse must help her conjure a beautiful silk purse for Mama. Bessie seemed to have no objection, and Nurse was the wisest person in the whole world, except for Papa.

Unfortunately, the piglet shoved itself underfoot, sending Elizabeth into a tumble. Her older sister Jane arrived just in time to scream at the apparition rising from the muck. Nurse hurried to the scene to find one child tear-stained yet spotless—and the other covered in a thick coating of mud.

Hurriedly cleaned but still smelling strongly of pig-wallow, Elizabeth tried to explain things to her parents. Mama may like Jane best, she thought. But once she hears about my wonderful gift ...

However, Elizabeth was doomed to disappointment once again. Mrs. Bennet found the exploits of her second-born inexplicable, almost as maddening as the roar of laughter from her husband as he heard the tale. Nurse, however, smiled in relief. That laughter was the first natural sound to come from the master in many weeks.

The house had been strangely silent since the birth of Baby Catherine, known as Kitty. Despite the safe delivery, her mistress, ordinarily so voluble, remained preoccupied and distracted. This baby brought no joy to Longbourn, except for Jane, who loved peeping into the cradle to smile and coo at her. Elizabeth found the infant dull company. And hearing her father complain about the new arrival and the lack of an heir made Elizabeth worry: If Papa does not like Kitty, should I?

On one of her father’s rare visits to the nursery, he paused for a moment and said, “My dear Mrs. Bennet, what a smiling picture you make in your white gown, dandling your newest darling on your knee while our eldest gazes on in raptures. You quite put me in mind of Mr. Romney’s Countess of Warwick and her Children—but exceeding them in beauty.”

Then he scooped up Elizabeth from where she was playing on the floor. “But so much perfection is not for the likes of us, eh, Lizzy?” Ruffling her hair as he led her away, he added with a chuckle, “We are better suited to Bessie and the stables.”

Holding onto his strong hand, Elizabeth thought: Does Papa not think that I am pretty, too?

But when he hoisted her up in front of him on his favorite bay, she forgot her complaint as Orion became the shared throne from which they together surveyed the magical landmarks of their kingdom.

Mr. Bennet spoke to his daughter as they rode: “Look, Lizzy, that field is planted with wheat. Here is the blacksmith’s shop. Over there is Abel Smyth’s farmhouse.”

“Faster, Papa, faster!” she pleaded.

Smiling, he urged the horse into a trot. Elizabeth cried out with glee.

But then—disaster!

On a deserted stretch of road, Orion stepped into a fox’s hole and broke his fetlock. The horse crashed to the ground, screaming in pain. Mr. Bennet was barely able to leap free of the falling animal. He managed to protect his child, clutching her tightly against his chest, but broke his own leg when he landed.

Elizabeth saw blood gushing from Orion as he thrashed on the ground; her father was white-faced and unable to stand. This is my fault, she thought.

“Papa, I am sorry,” she wailed.

He clenched his teeth, saying as evenly as he could, “Lizzy, calm yourself. I want you to walk back around the bend.”

“No! I shall not leave you,” she insisted.

Realizing she was paralyzed with fear, he softened his voice. “You are a brave girl, and you must fetch some help.”

The horse screamed again in pain, causing Elizabeth to throw her arms around her father. “Please,” he said grimly, “walk around the bend and run up to the first person you see. Tell them to come at once.”

Tears fell from her darkened eyes as Elizabeth grasped his meaning. Trembling, she jumped up and ran as fast as her pudgy legs would carry her to bring aid.

Afterwards, Mr. Bennet praised her to everyone. “Lizzy is my brave girl,” he would repeat often.

While Mr. Bennet recovered from his leg fracture, he often invited Elizabeth into his library. She sat on the floor, her arm gently wrapped around his injured leg, as he read his favorite Robinson Crusoe to her.

The accident forged a special bond between father and daughter. It also left Elizabeth, usually so courageous, with an enduring dread of the saddle. She never rode if she could avoid it, even when her mother and sisters made sport of her. Instead, she became a great walker on her travels about the estate.

Normally mothers read aloud to their children before they learned to read for themselves. Mrs. Bennet mistrusted female education but did enjoy the fashion periodicals. So, before learning to read their letters and primers, her daughters discovered the larger world in the form of sleeve lengths, bonnet-styles, and coiffures.

When Elizabeth and Jane were five and seven, their father encouraged word and song play to sharpen their ears for the rhyme and meter of poetry. One spring day, the girls were with him in the garden when Mrs. Bennet and Nurse came out to fetch the children for their dinner. Mrs. Bennet heard Jane rhyming “star” and “far” and remarked, “I never bothered my head with such things at their age.”

“Yes,” her husband responded, “you prefer to keep it unfurnished.” Puzzled, Elizabeth asked what “unfurnished” meant.

“It means empty,” her father replied.

Gleefully, Elizabeth chanted: “Empty head, empty head, Mama has an empty head.”

“Miss Elizabeth!” Nurse scolded. “You should not say such a thing!”

Surprised, Elizabeth looked at her father. “But, Papa...”

Mr. Bennet, not meeting her eyes and with a strange expression on his face, said, “That will do, child. Go in to dinner at once.”

Over her shoulder, Elizabeth saw her mother glaring at her father, but his eyes remained on his book.

In due course, another daughter, Lydia, joined the family, so that along with studious Mary, there were now five Bennet girls to occupy Mrs. Bennet and alternately plague and amuse their father.

Some years later, Nurse placed young Lydia on a rug spread on the grass. The older girls were nearby, playing “Princess and Pirate,” a game Elizabeth had invented. Elizabeth, the fearless pirate, heard Lydia cry out and turned to see a large red fox menacing her, ready to wrest a sweet from her tiny fist.

“Avast, ye beast!” Elizabeth leapt from her crow’s nest in the beech tree and dealt the “enemy’s” snout a hard blow with her wooden sword. The vixen slunk away.

Jane rushed the young ones to the safety of the house and told their parents of her sister’s bravery! Mr. Bennet smiled fondly at his intrepid child, but her mother seized Elizabeth by the shoulders, saying, “You are too boyish, Miss, and will surely come to no good stabbing wild animals. I am at my wit’s end! What must I do to teach you to behave like a young lady? Your sister Jane does not charge about with toy swords. There shall be no dinner for you, Lizzy, and I forbid you to go anywhere near another tree!” Mrs. Bennet collapsed, exhausted.

Blinking away tears, Elizabeth retreated. When Jane reached for her hand in sympathy, her sister snatched it away. She refused even to taste the treacle tart her older sister smuggled to her from the dinner table.

By morning, Jane approached Elizabeth gingerly: “Mama is afraid you will not marry if you do not change your ways.” She paused. “But I want to help you.”

“Why do I have to marry?” Elizabeth demanded.

“It is the way of things—what girls must do,” Jane replied. “Do you not wish for a lovely home, a good husband, and sweet children?”

Elizabeth stayed silent. She was unsure what she wanted but knew it would be different from everyone else’s dreams.

More serious worries invaded Longbourn in the days that followed. Lydia started crying whenever she swallowed her food, and in quick succession all of the Bennet girls developed cases of the putrid sore throat. Even Mr. Bennet succumbed to the disease. Though light-headed and ill, Elizabeth could see a different side of her mother, nursing the family even though she was worried and exhausted. Luckily, all the victims regained their health and thrived.

As Elizabeth grew older, she took to the habit of long walks in the countryside, especially when life at Longbourn became too stifling. To escape her sisters and her mother’s endless litany of corrections, Elizabeth especially enjoyed visiting neighboring Lucas Lodge.

Despite the cacophony and confusion created by so many children, it was a harmonious home. Elizabeth grew very close to Charlotte, the oldest daughter of Sir William and Lady Lucas. She was a full seven years older than Elizabeth, yet each was attracted by the other’s intelligence and humor.

Like Jane, Charlotte possessed a balanced temper. But to Elizabeth’s eyes, her friend seemed remarkably clear-headed, trying to conduct her life with no romantic illusions.

When Elizabeth complained about her mother’s preference for Jane, Charlotte said, “Does any girl find it easy to have a beautiful sister?”

“Everyone loves her best!” Elizabeth said.

“And why do you love her, Lizzy?” asked Charlotte.

Elizabeth paused. She knew it was not only Jane’s beauty that attracted everyone, but also her sweet temperament. Jane saw the good in everyone, which Elizabeth, with her more critical mind, found impossible to do.

Mrs. Bennet approved of their friendship: “I daresay Charlotte is a very nice girl. She is a fine choice of companion, Lizzy, for as she is so very plain, your looks will always show to great advantage,” she added with great relish.

Her mother was already preparing her strategy for next month’s Assembly in nearby Upper Garvie, which first involved persuading her husband to attend. “It will be the first time our Lizzy dances,” Mrs. Bennet said in her sweetest voice. “Do come and support our daughters, Mr. Bennet.”

Looking up from his breakfast, he replied, “A ball is something every woman is eager for—and every man over forty contemplates with dread.”

Sixteen-year-old Elizabeth kept her voice—and her disappointment—to herself. This is to be my “coming-out,” she thought. Cannot Papa see how I look forward to it?

But Elizabeth’s melancholy thoughts were soon lost in the excitement of preparations, for her mother knew to a certainty how to dress with style. Always, Mrs. Bennet’s daughters would have everything necessary to shine at the ball. And this one would put Elizabeth on an equal footing with Jane, who had been “out” for two years.

Elizabeth remembered her envy when Jane, dressed in a beautiful new gown, made her entry into Society. Her Aunt Gardiner had sent the garment from London for Jane’s special occasion, and Elizabeth assumed that she, too, would receive a similar costume to wear to her first ball. When a small package arrived from town, she wondered how a gown could be contained in so little space. Alas, her aunt and uncle had sent their niece an exquisite leather-bound book designed for use as a personal journal. Vexed beyond endurance, Elizabeth tore the pages from the lovely book, regretting her temper only after she had reduced the gift to shreds.

Later, she begged her mother: “Please, please. Jane had a new gown, why cannot I have one?”

“Her gown is perfectly fine for you to wear, Lizzy. Do stop acting like a child.”

Oh, no! Now she would have to make do with Jane’s gown, altered to fit herself.

Stubbornly, Elizabeth decided not to be deterred from enjoying her first ball. She only wished to spend the entire night dancing and taking pleasure in the company, for rumor had it that John Masters would be there.

At the last moment, Jane could not attend, confined to her bed with a painful earache. All the better chance to shine at the ball, Elizabeth thought. Then, ashamed of such selfishness, she brushed it away quickly—something she had discovered helped her change moods.

Instead, she thought of John Masters. The young man was renowned throughout Upper Garvie for his skill with a chaise and four and his tall, striking figure. Elizabeth confessed to her friend Charlotte that Masters put her in mind of the bronze Apollo in her father’s library.

She could scarcely believe her good luck when a flurry of activity at the entrance to the ballroom resolved itself into John Masters. Elizabeth was glowing as the young man led her to the floor for the first dance, just as she had dreamed! He was an accomplished dancer and knew just how to address a young lady: “You are remarkably light on your feet and dance so well that it is a pleasure to be your partner.” Elizabeth blushed prettily.

Smiling broadly at the end of the dance, Masters indicated he would certainly call at Longbourn soon. Flattered, Elizabeth replied, “You will be most welcome, sir. My parents are pleased to entertain our neighbors.”

There were other very acceptable partners during the evening—everything conspired to ensure that Elizabeth’s first ball was delightful. When they returned home, her mother remarked, “You looked your very best tonight, Miss Eliza, you enchanted the local swains.”

Her father greeted his wife’s comments with a loud “Ahem!” and a quiet peck on Elizabeth’s cheek.

And so Elizabeth was forced to acknowledge there were times her mother knew just the right words to set one up!

True to his word, Mr. Masters paid a visit to Longbourn the day after the ball, riding up to the house on his majestic mount, Conqueror. “He is bee-u-ti-ful!” cried Lydia, spying from an upstairs window. But the younger girls were not invited into the drawing room where Mrs. Bennet received him with great courtesy. Mr. Bennet, forewarned of the possibility of the visit, had fled to the home farm.

“Oh, Mr. Masters,” Mrs. Bennet began, “you and Lizzy made such a handsome couple last night. I am so glad you were her first partner.”

Mr. Masters carried flowers that they assumed were for Elizabeth, but when Jane, feeling better, entered the room, Masters bowed and presented her with the blossoms: “I had hoped to have the first dance with you, Miss Bennet. In your absence I was most honored to partner your sister.”

Elizabeth could scarcely believe this was happening. It was my “coming-out,” yet it was Jane he wanted to dance with, Jane he wants to please now. This is insupportable!

She felt a flush rising to her cheeks. “We saw you arrive on quite a beautiful animal,” she said, surprised at the steadiness of her voice.

Masters gave her a proud smile. “Yes, Conqueror is quite my favorite. We are inseparable.”

“How wonderful, at least, that you are steadfast in some things.” Then, looking at neither her sister nor her mother, Elizabeth rose abruptly and left the drawing room.

Alone in her room, she threw herself on the bed and pounded a pillow. How could he humiliate me so? I was the one he danced with. I should have received the flowers, for the sake of politeness if nothing else!

Rising to her feet, she strode about the small room, picking up objects only to put them down again until a knock at the door brought her to a halt. The door opened slowly and Jane looked in, her expression anxious and distressed.

“Lizzy? Have you caught my indisposition? You left us so suddenly, and Mr. Masters left soon after. Mama made your excuses to him.”

Elizabeth whirled to face Jane. “How can I ever be happy when I am always in your shadow? What man will notice me while you are nearby?”

Jane, stunned by this utterly unexpected assault, burst into tears. “I was not even at the ball last night! Mr. Masters is at fault—he is the one who has offended you.” She took a deep breath. “Dear Lizzy, I love you. I would do anything in the world for you. I hope you know that.”

Elizabeth now found herself sobbing on Jane’s shoulder. “He insulted me, Jane, and I took it out on you with foolish jealousy.”

They sat for a moment in silence. Then Elizabeth said somberly, “I may always envy you your beauty, Jane, but never again will I hate you for it.”

When Elizabeth related what had happened to Charlotte Lucas, her friend frowned in thought. “Mr. Masters was less than serious in his intentions to either of you—and quite ungentlemanlike. Most young men must find a rich girl to marry, for even among the wealthy, younger sons must shift for themselves.”

“But in books, heroes do find true love with women who are poor but beautiful,” Elizabeth argued.

“In your novels, perhaps, Lizzy. But not in life.”

“That is so unfair!” Elizabeth fumed. “There must be true love in this world, else our greatest poets would not write of it.”

Her friend remained unconvinced. Sorely disappointed, Elizabeth walked slowly back to Longbourn, to find Mrs. Bennet in ecstasies! A letter had arrived from her London relations!

Mrs. Bennet’s brother, Edward Gardiner, earned a handsome income from the cloth trade in the Metropolis. He had married an educated woman, whom Mrs. Bennet regarded as a sister. The families often exchanged visits, but this letter contained a special invitation for both Elizabeth and Mary, the family musicians, to a much anticipated concert by a renowned female pianist and composer.

A smiling Jane embraced her sister. Recent disappointments were forgiven and forgotten. Mr. Masters, Upper Garvie, and Charlotte’s disheartening sentiments all sank beneath this evidence of Mrs. Gardiner’s generosity. Mary practiced her scales harder than ever. Elizabeth could think only of London and the novelty of the grand performance to come.

However, her impatience was unexpectedly diverted. While accompanying his wife and daughters to their customary Sunday service, Mr. Bennet, ready to doze through the sermon, listened instead with unusual interest to the visiting vicar. Astonished, he recognized the booming voice of an old schoolfellow, Everard Twill, coming from the bald-headed clergyman before him.

Mr. Bennet eagerly revived his old friendship, and the Bennet ladies soon took to visiting with the Twills, temporarily in residence at the Vicarage. Anne Twill, an orphan, lived with her uncle and his wife, helping with their eight children, and Elizabeth particularly enjoyed her company. They soon found much common ground in literature, agreeing that the Castle of Otranto was too absurd for words but that Pamela was quite satisfying.

By the time the Twills returned to their home in Winchester, the young women promised to correspond and were soon “Elizabeth” and “Anne.”

Several months later, the post brought disturbing tidings. Anne wrote in some distress that despite her five years spent assisting her uncle’s wife, that lady had now decided to give the favor of the position in her household to one of her own relations. Without the support of the Twills, Anne’s only hope was to seek a husband.

On hearing the news, Mrs. Bennet merely shook her head. “With only £50 a year to call her own, that girl will have a hard time finding a suitable mate.”

Perturbed about her own daughters’ futures, Mrs. Bennet wrote to the Gardiners, begging them to make the most of the girls’ London visit.

At the long-awaited concert, Aunt Gardiner was pleased to notice a friend sitting nearby, a Mrs. Wellfleet, attended by her son Edward. Young Ned was down from his medical studies at the University of Edinburgh, following in his father’s footsteps. Not only did the senior Wellfleet have a fashionable practice, he had compounded a popular medicine.

The two parties exchanged introductions and chatted pleasantly. Elizabeth was delighted by Ned’s enjoyment of music. Mrs. Wellfleet promised to call on them at Gracechurch Street the very next day.

Ned Wellfleet accompanied his mother to the Gardiners’ with evident pleasure. As he sat in a corner with Elizabeth, she found his concentration on her every word gratifying. But he disturbed her usual composure, and she was annoyed to find herself blushing.

The next evening the Gardiners invited her to a small private ball, where Ned asked her for the Allemande. Elizabeth happily agreed. How sure his steps! How naturally he responds to the music! She was elated and began to feel the power of being thought desirable by a very attractive man. So this is what it is like for Jane.

Unfortunately, her joy was interrupted by her duty to dance with others. Ned remained with Mr. Gardiner, saying, “I cannot imagine a young woman of greater outer or inner beauty than Miss Elizabeth.”

The older man smiled. Mrs. Gardiner will be most interested in this conversation!

The night before the girls’ visit was to end, the Wellfleets hosted a dinner for the Gardiners and their nieces. Ned’s father welcomed his guests warmly, but Elizabeth, meeting Dr. Wellfleet for the first time, sensed that she was being scrutinized.

Dr. Wellfleet paid particular attention to the two girls after dinner. Mary, at her age flattered by the invitation and eager to please their host, was expansive in her description of the Bennet family and Longbourn. Raising his eyebrows, the doctor inquired, “Miss Elizabeth, am I to understand that you have four unmarried sisters but no brother to inherit your father’s property?”

Mr. Gardiner looked up from the post he had taken by the window. “The sky has grown quite dark.” A rumble of thunder underscored her uncle’s words. “I must get the ladies home before the storm begins. Thank you for a most pleasant evening, sir!”

Elizabeth was crushed. She was to leave London tomorrow but took comfort in the warmth of Ned’s farewell.

She could not expect to hear from Ned—only engaged couples might properly correspond. But she was confident that her Aunt Gardiner would furnish tidings of Ned and his family. When no letter came from Gracechurch Street in answer to several of her own, Elizabeth made excuses: Aunt must be much occupied with her children now that Mary and Elizabeth were not there to join in the nursery games.

Finally a letter arrived from Mr. Gardiner for Mr. Bennet. He read excerpts at breakfast: Mrs. Gardiner had been busier than usual with the children, who had the croup. Dr. Wellfleet had called to physic the sick children and had asked after the Longbourn nieces.

The good doctor had explained that Ned had undertaken an extended trip, investigating possibilities for selling the Wellfleet Elixir beyond England. Royal Patents for such things were more generally issued to gentlemen with medical degrees from Scotland—and Ned had trained in Edinburgh.

Folding the letter quickly, Mr. Bennet went back to his newspaper. Elizabeth stared at him, burning to ask what else Uncle Gardiner had written. But Mr. Bennet rose abruptly, leaving the room without so much as a glance at her.

She followed her father out of the room to his library, where he extracted some papers from the vast number of letters and pamphlets accumulated on his desk. “Not now, Lizzy,” he said. “I have business with the steward.”

He escorted her from his domain, but she stood irresolute in the hall. Had her father shared the whole of Uncle Gardiner’s letter? Was there something he was hiding from her? Some trifling Wellfleet reference to herself perhaps?

She heard the sounds of her mother and sisters’ noisy departure for the nearby town of Meryton. The house was empty, and the servants knew better than to disturb the tranquility of her father’s library.

Elizabeth formed a desperate plan that was against her normal good sense. She was being pulled by feelings that came from deep within her heart, that she could no longer resist.

Opening the library door, she approached the desk and examined the papers lying there to identify the letter in her uncle’s hand.

Spying her own name on the page, she read:

It was to be expected, I suppose. Old Wellfleet noted his son’s preference for Elizabeth and made it his business to learn the details of the Longbourn entail. A bride with four sisters who would too likely become dependent on the Wellfleet fortune? Alas. My dear wife fears a deep disappointment for Lizzy and urges us to continued silence. To speak of it now can do my sister no good, and my wife prays Lizzy’s heart may as yet be untouched.

We both know that young women are not “rational creatures,” and all that Wollstonecraft woman’s ravings about how women are treated will never change this. Should Lizzy approach you, I beg you to give her what comfort you can.

Mr. Bennet found his daughter at his desk when he returned some hours later, the letter still in her hands. “What are you doing here?” he asked sternly.

In a trembling voice she pleaded, “My uncle’s rationale for Dr. Wellfleet’s behavior cannot be correct. Can it, Papa?”

He softened his voice. “Tut, tut, child. Matters of entail and provisions of income are most unfit for the feminine mind. Come away,” he urged.

As he gently escorted her from his study, Elizabeth realized her father had not contradicted Mr. Gardiner’s assumptions.

Her next days were painful. She felt abandoned and at a loss for what to do.

Then she remembered Uncle Gardiner’s reference to Wollstonecraft. Perhaps, if she knew what that touched on, she could calm herself.

Feeling ashamed for again invading her father’s privacy, for several days she ransacked the library’s reading tables and shelves. At last she found a tract written by a Mary Wollstonecraft, Thoughts on the Education of Our Daughters.

In the next weeks, Elizabeth devoured the book and sought out other writings by the author. She was fascinated by the radical thoughts she encountered: “If women be educated for dependence; that is, to act according to the will of another fallible being, and submit, right or wrong, to power, where are we to stop?”

Jane and Charlotte were uncertain about these ideas. But Elizabeth was sure Anne would find them fascinating. She wrote to her friend frequently about this strange author and her revolutionary philosophy.

Some time later Elizabeth was invited to make an extended visit to Gracechurch Street, prompted in part by a need for help after the arrival of the Gardiners’ latest child.

Elizabeth eagerly agreed, remembering the whirl of concerts, theaters, and salons. She might even encounter Ned Wellfleet! But once in London, most of her time was spent in the nursery. Boredom crept into the intervals between her few social engagements, sometimes even during them.

Correspondence with Anne Twill provided Elizabeth’s greatest consolation, especially with Anne’s announcement that she was engaged to be married! Her fiancé was a longtime friend of her Uncle Twill. Mr. Walter Fortune’s recent appointment as chaplain to the bishop of Peterborough had provided him the means to set up his own household at last.

Anne was excited about their upcoming visit to London. Mr. Fortune was to accompany the Twills to Town. There the elder Twills would advise the “young couple” on such furnishings as their new home might require and London’s warehouses supply.

Elizabeth wrote to her father, enclosing a tempting notice of an Antiquarian Book Sale; so he arrived in London in good time for the famous auction.

Elizabeth received a shock when she at last met Mr. Fortune. He seemed more a contemporary of the Reverend Twill than a match for Anne!

Though he frequently jested that their union was extremely “fortunate,” it seemed that Anne’s lack of fortune gave him license to find her inferior. Elizabeth was appalled at the way he corrected Anne’s mildest comments with, “Experiencia docet—‘experience teaches.’ We will soon cure you of your ignorance, my dear.”

Elizabeth turned to her aunt, speaking in an undertone: “How can Anne bear so meekly Mr. Fortune’s rude, dismissive behavior?”

Mrs. Gardiner agreed that his conduct was ungentlemanlike, but asked: “Lizzy, what reasonable choice has she?”

Vexed, Elizabeth considered a Wollstonecraft sentiment she and Anne had both admired: “It is far better to be often deceived than never to trust; to be disappointed in love, than never to love; to lose a husband’s fondness, than forfeit his esteem.”

Had Anne completely forgotten these wise words?

They all arranged to meet the next afternoon at Mr. Wedgwood’s showrooms to survey the exquisite porcelains on offer there. Mr. Bennet agreed to accompany the ladies on this excursion. The Gardiners would meet them there.

Mrs. Twill fluttered about the warehouse, her attention as much on the elaborately dressed customers as the superb chinaware on display.

“Oh, look, Anne—Lord and Lady Mainwaring! And beyond them is Dr. Tobias Wellfleet’s party. We could do no better than to take several bottles of the famous Wellfleet Elixir back to Hampshire. It is known to be endorsed by the Royal Family!”

Elizabeth eagerly searched in the direction that Mrs. Twill indicated and spied Ned Wellfleet! Her heart rose in happy surprise, until Mrs. Twill continued, “I wonder if the Wellfleets are here to purchase a breakfast set for their son and his new Scottish bride?”

The delicate teacup Elizabeth had been examining shattered in her hands.

“Have you hurt yourself?” her father asked in concern.

“Hurt myself? I think not, Papa.” Her voice was clear and cutting as she spoke. “Though I confess someone has caused me considerable pain today.”

Elizabeth had the satisfaction of seeing the discomfort on Ned’s face before she felt the sting in her hand. She looked down in shock to find a shard of chinaware deeply set into the flesh of her palm. As blood began to flow, she also realized she had captured the disapproving attention of everyone in the establishment.

The Gardiners all but spirited her away while her father paid for the damage. Mrs. Gardiner was silent as she removed the porcelain fragment and wrapped the wound in a handkerchief. Elizabeth had never been so publicly disgraced.

Her father’s mood grew worried on the coach ride home to Meryton. Elizabeth’s hand throbbed painfully, despite being carefully bandaged. She felt chilled and feverish by the last stage of the journey.

When they arrived at Longbourn, Mrs. Bennet immediately put her daughter to bed. In the days that followed, her mother gently applied unguent and bandages to her hand.

One night, Elizabeth unburdened herself of the events in London, especially her distress over Anne Twill. “Must I, too, spend my life with a husband who makes me unhappy?” she asked her mother. “It cannot be the only way to assure a roof over my head!”

Mrs. Bennet sighed. “If you had a brother, perhaps ...” she broke off as her daughter wearily nodded, only too aware that Longbourn could only be inherited through the male line.

“How else will you live, Lizzy?” Mrs. Bennet asked. “You could become a governess, I suppose, or a lady’s companion, or you could live with one of your sisters when they marry. But I do not think you would like the lot of a poor relation. No, that would not suit you at all.”

She gave her daughter a worried frown. “Do not complicate things, Lizzy. Just find yourself an eligible young man, and you will be content enough.” Reminiscence softened her handsome, if somewhat tired, features. “I never asked such questions as yours—I just set my cap at your father and caught him with my smiles. And you see how content we are!”

Mrs. Bennet suddenly gave her daughter an affectionate embrace. Elizabeth was so astonished at this motherly gesture that tears came to her eyes.

“Rest now, child. You will be better soon.” Satisfied with her good advice, Mrs. Bennet took her leave.

Elizabeth lay awake, enjoying the maternal warmth she felt. But soon she was plagued with painful reflections. The father she had always revered now seemed very much less than wise.

Papa knew about the entail all along, she thought ruefully. Yet he always took the easier course, never setting aside anything to support us after he was gone. No wonder Mama has been so frantic!

Slowly, Elizabeth recovered, with only the faintest of scars to mark her mishap. She resumed her life of walks and country pleasures. Mrs. Bennet redoubled her efforts to find husbands for her daughters. And, a few days before her twentieth birthday, Elizabeth received a carefully wrapped parcel from the new Mrs. Fortune.

She opened it immediately, to find A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, the book Elizabeth had given her friend. A note accompanied the volume:

September 10, 1813

Dear Miss Elizabeth Bennet,

I hope this letter finds you and your family in health. Mr. Fortune instructs me to return your gift. He also asks me to express his shock that Mr. Bennet would permit you any familiarity with this “pernicious volume.” I must also inform you that my new duties as the wife of a Chaplain render it impossible for me to continue our correspondence, or indeed, any further acquaintance with you.

Very truly yours, etc.,

Mrs. Walter Fortune

Elizabeth stood for a long time with the letter and the volume in her hands, torn between tears at losing her friend and fury at this enforced betrayal of Anne’s intellect and character. As this very book had warned, Anne had chosen submission.

What will become of her, tied to that loathsome, detestable brute!

One thing Elizabeth was sure of: No one would make her follow Anne’s example, no matter how high and mighty. Was there no means to change the way of the world? Neither wit nor spirit, family nor philosophy seemed equal to the task.

I will find a way, Elizabeth promised herself, crumpling the offending letter and hurling it into the fire.

And woe to any man who dares treat me with contempt or condescension!