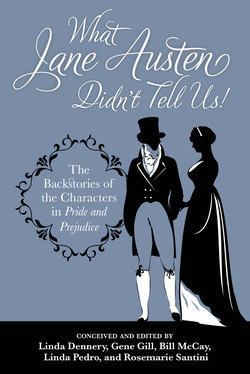

Читать книгу What Jane Austen Didn't Tell Us! - Austen Alliance - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Fitzwilliam Darcy by Bill McCay and Rosemarie Santini

ОглавлениеMr. Darcy soon drew the attention of the room by his fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien; and the report which was in general circulation within five minutes after his entrance, of his having ten thousand a year.

—Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

Although he was the tallest of the group of boys in the gallery, even on tiptoe Fitzwilliam Darcy’s fingers fell short of the old cavalry rapier above his head. Determined, however, the eight-year-old began prising at the weapon with the tree branch he had been using as a blade.

His friend Georgie Wickham cleared his throat nervously. “Fitz—” he began.

“Am I not a Darcy of Pemberley?” young Darcy cried as he struggled to work the blade loose. “Who better to wield my great-grandsire’s sword?”

As he spoke, he succeeded in freeing the weapon from its mountings. Georgie leaped to try and catch the sword, but his effort was too late. The point landed heavily in the fleshy part of his hand, near the thumb.

Georgie’s howl of pain drowned out the weapon’s clatter on the floor. He cupped his hands together, a flow of red beginning to fill them.

Darcy sprang to help his friend, the steward’s son, pulling out a handkerchief to try and stanch the flow. Better to lose a piece of linen than to allow bloodstains on the gallery rug. “Get help,” he called to the other boys, who ran in all directions.

Luck attended their actions, as the hostler’s son quickly returned with an upstairs maid.

“Master Fitzwilliam, whatever are you—” She broke off as she saw the bloody cloth, taking Georgie’s hand in hers. With the arrival of a grown-up person, the injured boy’s eyes filled with tears. At seven years of age, there is only so much bravery to be found in a young lad.

The maid pressed the linen tightly, raising Georgie’s hand. “You did well with this, Master Fitzwilliam, but we must get this hand washed and bandaged.”

She paused for a moment as she took in the sight of the old sword on the gallery floor. Quickly replacing the blade to a safe haven, she hastened Georgie along to tend his wound.

The result of the adventure was that ever after, George Wickham bore a curiously hooked scar on his hand ... and the beloved sword was moved to a higher place on the wall.

“Our son is proud of his heritage,” George Darcy told his wife as they discussed the incident. “How else is he to learn?”

“Preferably by not injuring any more of the staff,” Lady Anne Darcy said, but she knew argument on this score was useless. Once her husband cited his heritage, the matter was closed.

The master of Pemberley was pleased to see his ailing wife show some spirit when she answered. It gave him hope that she was healing from recent illness.

Always, heritage ruled the very soul of Pemberley and the Darcy family. Great tapestries and portraits, even furnishings and weapons, relics of past generations could be found in every corner of the great house.

Had not an ancestor received baronies from the hand of William the Conqueror himself?

Had not a Darcy returned with news of Edward III’s victory at Crécy 280 years later?

For young Fitzwilliam, the ancestor who stirred his greatest excitement could be found in a large portrait near the sword he had tried to command. Sir Giles Darcy had led the Parliamentarian forces in Derbyshire.

The portrait of the grim-faced Sir Giles, dressed in half-armor from the great Civil War between King and Parliament, took up considerable space in the gallery—and in his descendant’s mind.

His father recounted the campaigns and battles of a gallant knight to young Fitzwilliam. But from the servants, the boy heard local tales where Sir Giles’s behavior was questionable. These stories always ended with the same refrain: “High-handed old Sir Giles might be, but canny as a fox was he.”

One thing the boy knew—those exploits, good and bad, had created the essence of the Pemberley estate, though later descendants turned the manor into the showplace it became. Young Fitzwilliam spent many afternoons impersonating the great Sir Giles, with a stick for a sword and a regiment composed of Georgie Wickham and various boys from the estate, under the complaisant eye of Mr. Darcy.

Perhaps it was the experience of portraying such a proud, high-handed figure that so marked the boy’s character. Or, perhaps it was his father’s taking him to a place where the lands of Pemberley spread as far as the eye could see, pronouncing, “A Darcy has held this land for more generations than you have fingers and toes. It is a great thing to be a Darcy of Pemberley, but a tremendous responsibility as well. You are the guardian of a great treasure and must keep Pemberley safe for the next generation.”

Young Darcy’s voice was fervent: “I shall, Papa,” he swore. “I will.”

Fitzwilliam Darcy was born in 1785, a difficult delivery that left his mother convalescent afterwards. He was a strong, active baby, large for his years, and capable of causing considerable chaos in the nursery. But he had a sweet nature and could be brought to behave if appealed to by someone he liked.

For some years he was the only child in the family. Young Darcy relished opportunities to escape the nursery and explore the great house, staring in awe at the portraits in the gallery, the elaborate staircases, the fine tapestries of battles and historical events involving his forebears.

Lady Anne’s father was an Earl, and while her husband’s branch of the Darcy family did not bear a title, they were known throughout Derbyshire for their wealth and property.

During his childhood, Master Fitzwilliam usually saw his father only once daily. Before George Darcy dressed for dinner, he had his son brought to him and then sent off to bed. In normal times, young Darcy spent breakfast or luncheon with his mother, but often she was not present due to illness. On occasion he was allowed to visit in her bedchamber, a dim place lit by her kindly maternal presence.

Most of his day was spent with servants. Cook could always be depended upon to present a sweet if the boy managed to make his way to her domain, and at both lessons and at play his constant companion was Georgie Wickham.

The boys were close, a pair of allies against their tutor and the upper servants. Together they learned their numbers and letters, history and geography, the rudiments of Latin and Greek necessary for higher education, and a little French.

Darcy disliked the rote aspects of learning but suffered through them for the ability to read. Georgie was bright but lazy. As the subjects became more difficult, he invented ingenious ways to avoid study.

After the ill-fated episode with the sword, Mr. Darcy engaged a fencing master for his son: “Having discovered which is the pointed end, it is better you learn how to inflict a wound by some other means than accident.” Young Fitzwilliam took to his lessons very seriously, quickly outdistancing Wickham.

Riding was another passion. Quickly the boy graduated from a docile pony to stronger mounts. He loved to ride around the estate with his father and the steward, James Wickham. While Wickham handled the business affairs of Pemberley, young Fitzwilliam explored the estate with his father and Georgie.

During the spring before he was to go to school, Darcy’s mother took to her bed for much longer periods than usual. Initially, the boy thought Lady Anne was ill again, but after a month he learned the truth—his mother was expecting another child.

The summer passed in considerable suspense, between hopes for a new brother or sister and worry about his lady mother’s precarious health. Fitzwilliam applied to his father to delay his departure for school, but George Darcy would hear none of it. “You will be in Derby, a short journey from home in case—” he broke off.

Thus, young Darcy took his place at the Derby School, as generations of the family had done before him.

Mr. Darcy had often expounded upon the traditions of the school—and the reasons for them. “It is a fine thing to run around with local boys and give orders, but there will be a time when you must rule this little kingdom. Derby will teach you to lead—but first you will learn how to follow.”

Young Darcy did his best to fit in as the term began, but with an anxious heart over the events at home. Then came the news that a baby, Georgiana, had joined the family.

The celebration was short-lived, however. Lady Anne’s strength had been severely depleted by childbirth, and she did not recover during the term of her confinement after the birth. Fitzwilliam returned home immediately.

Despite the most devoted nursing, Lady Anne grew steadily weaker. Young Fitzwilliam himself would bring her a bowl of broth, and thanks to his coaxing the ailing lady took more nourishment from him than the servants or even Darcy Senior could persuade her. But all efforts were in vain. Lady Anne passed to her reward before the infant Georgiana was two months old.

The loss of Lady Anne affected George Darcy considerably. Already proud of his exceptional heritage, he now became a fervent evangelist to young Fitzwilliam. Their family had declined again to three, with no more additions to be expected in this generation. George exacted rigorous oaths from his son to take care of his little sister.

Darcy Senior all but left the management of the estate to the Wickhams as he continued this familial indoctrination. When his sister-in-law, the Lady Catherine de Bourgh, arrived to offer aid, George Darcy quickly sent her off. Her family, the Fitzwilliams, were of good blood, as no doubt were others with the Darcy surname. But none of these lesser breeds bore the name Darcy of Pemberley. That honor and responsibility fell to George himself, his son, and the infant Georgiana.

After the funeral, the boy returned to Derby. Still grieving, he immersed himself in his studies and applied himself as stringently to sport, hoping through exhaustion to hold sorrow at bay.

He did his best to live by the customs of the school with a good grace. The practice of fagging, where the younger boys performed as servants for their older schoolfellows, went hard against young Darcy’s pride. Preparing toast for a sixth-form boy he would do, but bullying was another matter.

Darcy was tall for his age, strong, and in no mood for impositions. When a bishop’s son appeared at morning prayers with a blackened eye, Darcy stoically accepted a birching from the older students for his infraction of the rules. But that did not deter him—he continued to thrash would-be bullies until they steered clear of him.

He was an acceptable scholar, but not one for team sports: excelling at fencing, riding when he could, and rowing in a single scull. An unexpected excellence was his ability at the dance—the footwork needed in the fencing salle aided his agility, confirming the old saw about the best swordsmen being the best dancers.

In the all-male boarding school, Darcy heard many tales from the older boys about the fairer sex. He heard the same sort of stories from the Pemberley lads when he came home for summer. The boys he had led to reenact the exploits of Sir Giles had moved on to other adventures, it seemed.

Though not lacking in confidence, Darcy felt a certain self-consciousness around young ladies, which he hid behind an almost gruff manner. His fellows might tease him for this reserved style, but he maintained it for the rest of his time at Derby.

With the passage of time, Darcy moved on to Cambridge, following family tradition once again. He arrived at the University with a reputation for wealth, for sporting prowess ... and for pride. Many of his fellow scholars sought to cultivate his society, if only because he had a ready purse for a pint, a meal, or any other entertainment.

But Darcy fairly much trod his own path until George Wickham came up to Cambridge, thanks to the generous financial support of Darcy Senior. At first, Darcy embraced the friend of his youth. He could not, however, miss the changes in Wickham’s character—or perhaps, the tendencies already present from childhood that now found full expression in the relative freedom of University life.

The laxity of the officials had turned the great Universities into schools for scandal. Classics, Divinity, or Mathematics were no competition for drink, cards, dice, and the pleasures of the town.

Darcy freely tasted these pursuits on his arrival at Cambridge, but he also pursued his studies.

Wickham, on the other hand, plunged into this raffish society whole-heartedly, ignoring lessons or tutorials and surrounding himself with a collection of disorderly personages. After a term of this behavior, Darcy began prudently to distance himself from Wickham and his ramshackle admirers.

However, Darcy himself narrowly escaped disgrace when he found himself inebriated, abandoned by his fellows, and locked out of his College. Happily, he was rescued by an undergraduate whom he had never met before, one Charles Bingley.

Gratitude for the timely assistance and Bingley’s congenial nature overcame Darcy’s habitual reserve, and they embarked on an association that soon became a friendship.

Wickham, on the other hand, managed to embroil himself in scandal. Caught on the stairs between a tutor and a porter, he was forced to fling a sheaf of scurrilous engravings out a window to avoid being caught with them. The pictures, of females in various states of undress, fluttered throughout the forecourt of the College.

Such crass conduct forced Darcy to curtail his association with Wickham. Since he had no wish to expose Bingley to such a character, he arranged that the two never met.

Instead, it was Bingley who accompanied Darcy into Society at University and in London. While Darcy provided entrée to high-flown social circles, Bingley’s convivial spirit and charming manner carried the day.

The friendship was firmly established when Bingley prevailed upon Darcy to visit Yorkshire and meet his family. Darcy’s first dinner in the Bingley house took him somewhat aback, however.

“Mr. Darcy.” Charles Bingley Senior pronounced Darcy’s name as if he were tasting it. “You are most welcome indeed. Whatever you require, merely let me know and it shall be provided, every jot and tittle, I say!”

His voice took on a gloating tone. “Mr. Darcy of Pemberley at my table will knock many a fine neighbor off his high horse.”

Darcy wondered at this outburst, so full of tradesman’s references. But Mrs. Bingley recovered the situation—with a weary but genuine smile. “Forgive us, Mr. Darcy. To my husband, you represent the latest chapter in a long, long tale entitled Vengeance on the Peacocks of York.”

Now her husband and children protested, but Mrs. Bingley faced them all. “I do not believe our guest will take a bit of plain speaking amiss.” She turned to Darcy. “For my part, sir, I honor you not for any regard you may bring our family, but for your friendship with my son.”

While Darcy learned forbearance for Bingley’s rough diamond of a father, it was Mrs. Bingley’s openhearted warmth that won his estimation. He found her to be a modest lady of gentle manners, every bit the model of her son’s glowing descriptions. Bereft of his mother for some few years, Darcy found himself warming to this good lady as he had to few others.

As Bingley’s time at University came to an end, Darcy and Bingley enjoyed exploring the pleasures of Society. Several years passed in routs and Assemblies, house parties, and travels to picturesque corners of Britain. Together, Darcy and Bingley cut quite a swath, reveling in the entertainments available, though Darcy took care to avoid the numerous snares laid in his path by mothers hopeful of securing an impressive husband for their daughters.

Then, in the winter of 1808, a letter came to Bingley that his mother was unwell. He and Darcy returned to York, and the diagnosis—lung fever. After a long, lingering illness, Mrs. Bingley passed away. Young Charles was heartbroken. Darcy found himself keenly touched by the loss of that good lady. But Mrs. Bingley’s death affected her husband most of all. Worn and ill after caring for his wife, he seemed to lose all interest in life and soon followed her into the churchyard and the new family tomb in Yorkshire.

Not long after the funeral, Darcy received a visitor at his family’s London house. Charles’s sister, Caroline Bingley, was dressed in black crape, crimped and styled into as fashionable a version of mourning clothes as he had seen.

“I was at Weatherly’s, the jeweler, to collect the mourning rings Charles had commissioned. Papa wanted you to have one.” She imperiously gestured to the footman accompanying her, who produced a small box.

Darcy opened it to find a finely wrought ring featuring a miniature painting of an antique column with the initials “C.B.” on it, the whole surrounded with tiny pearls. The outer side of the ring itself was covered in black enamel, and within he saw the name “Charles Bingley” engraved.

“It is very handsome,” Darcy said.

“Papa especially ordered that you should have it,” Caroline said. “And I took it upon myself to see that this bequest was promptly carried out.”

“I would have expected your brother to undertake this responsibility,” Darcy responded.

“Ah, Charles.” Caroline started a dismissive wave of her hand and then thought better of it. “He has more than enough responsibilities to deal with at present. Father left an inheritance, a fine sum I am told, that Charles is to use in securing an estate. It was Papa’s final wish.”

Darcy nodded. Such a purchase would mark the crowning step in the Bingley family’s rise from those fortunate in trade to the ranks of gentlefolk.

“How much easier my heart would feel to know that Charles would have recourse to someone older, wiser. Someone such as you, sir.”

Darcy quickly answered. “Please tell your brother that he can rely on my assistance in any matter that might trouble him.”

“I shall quite rely upon seeing you soon again. Pray forgive me, but I must ensure such little society as I can enjoy.”

Darcy understood. In mourning, Caroline must retire from Society—and meeting any eligible suitors. He responded with friendly words but without encouragement for any romantic hopes.

Mere months later, tragedy touched Darcy much closer. His father was stricken by a paralytic fit, leaving the right side of his body useless. George Darcy proved to be a difficult patient, abusing the servants as they tried to tend him and disturbing young Georgiana. Darcy returned to Pemberley and a series of stormy scenes as he undertook to nurse his father. His filial devotion served to mitigate George’s pain, and the two were reconciled.

“I leave this world peacefully enough.” The words came painfully from the elder Darcy’s half-paralyzed lips. “To you I entrust Pemberley—and Georgiana’s future.”

George Darcy’s eyes burned as he clutched his son’s hands with his single good one. “Cherish them—and provide an heir to continue the family heritage.”

His own eyes clouded with tears, young Fitzwilliam promised to follow his father’s strictures. Soon enough, George Darcy died.

Scarcely, it seemed, had George Darcy been interred when Lady Catherine de Bourgh appeared at Pemberley, eager to offer counsel—and, of course, to suggest a wedding between her daughter Anne and the Pemberley heir. Because of Lady Catherine’s overweening will, his gentle mother, to preserve peace, had given assent to the match when Darcy was a child.

While not explicitly rejecting his aunt’s schemes for directing his life, Darcy was able to fend her off, pleading the need to care for Georgiana ... and a considerable amount of unattended business to be dealt with at Pemberley.

During the elder Darcy’s illness, much had been forced onto the shoulders of his steward, James Wickham, whose own health had suffered, leaving much undone. Thus young Darcy thrust himself into the requirements of managing the estate.

One of the first things to be dealt with was the matter of George Darcy’s will. After generous bequests to various faithful servants and charitable donations, there was one troublesome legacy:

To my godson, George Wickham, I bequeath the sum of £1,000—along with earnest hopes that my heir will furnish this well-beloved young gentleman with such advantages as his chosen profession might allow. Should the said George Wickham undertake Holy Orders, it is my express wish that he might succeed to the benefice of Kympton as soon as it should become vacant.

After witnessing Wickham’s exploits at Cambridge, Darcy could imagine no one less suitable for life as a clergyman. He did not, however, burden George’s father with this information. The elder Wickham was ill, and indeed within weeks his own funeral ensued.

Soon thereafter, a letter arrived from George Wickham, advising Darcy that he had decided not to pursue Holy Orders and considered turning his attention to the law, the only drawback being that the interest on his bequest was insufficient to meet his needs during his course of study. If, however, he could receive some goodly sum in lieu of the promised church preferment, this would be readily accepted.

Thus Darcy parted with £3,000 in return for an undertaking from Wickham, renouncing his expectation of any church living. Darcy was unsure as to what course in life his former friend would actually follow, but he was certain that this transaction brought an end to their connection.

He turned his mind instead to restoring Pemberley to sound management, rectifying things that had been ignored. Among his concerns was the plight of the poor in the neighborhood. When he consulted with the local vicars for advice on this subject, the most helpful was the Rev. William Graham, vicar of Kympton.

That good and honest man readily admitted that his knowledge in this sphere came from his daughter, Cassandra, who devoted herself to charitable works.

When Darcy applied to the young lady for advice, he found himself struck as much by Cassandra Graham’s loveliness as her piety. Her slim form and luminous dark eyes gave an immediate impression of ethereal beauty shadowed by a sense of sadness that worried him.

At first, Darcy attributed her grave manner to shyness. As she got to know him better, Cassandra displayed a mischievous side. “Is it true, what Harold Cheney told me the other day? That you once threatened to invade Hopewell Hall with all the boys of Pemberley?”

“I was nine years old at the time,” Darcy replied, but he could see the laughter in her eyes. “My intent was to commemorate an exploit of an ancestor, Sir Giles Darcy, who threatened to plunder the hall and was rewarded with a rich ransom.”

“And this Sir Giles was your hero?” Cassandra asked.

“Yes,” Darcy admitted with some embarrassment. “That was before I could read more about him in the Pemberley archives. He was accused of betraying the Parliamentary cause and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Somehow he survived that and the Restoration of the monarchy, actually serving in the royal court before his death.”

“Not all heroic, then?” Cassandra inquired with a laugh.

“As I fear so much of history is not,” Darcy confessed, joining in. “He did, however, keep Pemberley safe.”

During the pleasant days of springtime, he visited often with Cassandra, devising all manner of means to bring a smile to her face. Often he teased her, invoking the Cassandra of ancient legend. That mythological namesake had the gift of true prophecy, but was cursed by the god Apollo never to be believed.

As time passed, Darcy came to realize his attachment to Cassandra was much more than mere friendship. Believing his feelings were reciprocated, he confessed his love to her.

“Sweet Fitzwilliam, that cannot be,” she said softly.

He immediately set out to reassure Cassandra, imagining her diffidence arose from concern over his heritage. “Have no qualms about the difference in our stations,” Darcy exclaimed. “Your father is of gentle birth and all that is respectable.”

But Cassandra insisted, “He is also a third son, far from the family’s line of succession—and patrimony. You must consider the reservations that members of your own family will have.”

“I believe that all you suffer from is an excess of humility,” Darcy declared. “Further, I believe you return my affections. Dearest, you do love me, and we will be married—nothing and no one will stand in our way.”

“I fear the matter is not so simple as that.” Cassandra fought tears as she spoke. “You should know—”

But he ignored her reservations, silencing her with a kiss. “Hush, my beloved. Nothing will stand in our way.”

The next day, he wrote to the Earl of Bleaklow, requesting an interview. When he arrived at Bleaklow Park to announce his plans, however, he found his cousin, Colonel Richard Fitzwilliam, and Lady Catherine de Bourgh in attendance.

“When you contacted my brother, I assumed you were coming to set an appropriate date for the marriage to Anne and felt we should all be here to celebrate.” Lady Catherine’s triumphant expression slipped slightly. “Although, certainly, the correct course would have been to apply to me, first.”

Confronted with a phalanx of Fitzwilliams and aware of Lady Catherine’s matrimonial machinations, Darcy lost his resolution. He cudgeled his brain to devise some alternative reason to see the Earl. “I—I beg pardon, dear Aunt,” he said, stammering slightly as he began. “I came to Bleaklow with quite a different end. My father’s passing has of course been a grievous loss. In addition, however, my father’s man of business also went to his reward. The minutiae of running Pemberley have grown quite onerous, and I have determined to find someone to take care of the property. Uncle Derwent, I hoped you might advise me on this subject.”

The Earl was quite surprised at this request, but gave his assent, suggesting that Darcy talk with the lawyer responsible for the management of the Bleaklow estates. Lady Catherine left them to it, none too pleased, and after a convivial glass with Colonel Fitzwilliam, Darcy escaped—though failing in his purpose.

Returning to Kympton, he found Cassandra abed ... ill. He rushed to her side, taking a hand that seemed almost translucent as a spirit’s. But despite her frailty, Cassandra’s eyes seemed to glow with a brighter light than ever. Confronted with this, Darcy’s words of comfort caught in his throat.

“Fitzwilliam,” Cassandra said quietly, “I am not long for this world.”

When he protested, she closed her eyes and slept. Frantic, he spoke to the vicar, who sadly shook his head. “I fear Cassandra has known of her illness for some time but could find no way to tell you.”

“I cannot believe—”

The vicar’s expression turned to one of pity—and pain. “I know you love my daughter. Cherish her, Mr. Darcy, for all too soon she will be taken from us. Our doctor says it is consumption, of the most virulent kind.”

As summer turned to autumn and Cassandra grew weaker, Darcy despaired. This is a punishment upon me for my cowardice in not declaring my love, he thought.

Cassandra did her best to soothe Darcy’s distress. “You are young and strong, and have a long life ahead of you.” Her voice grew softer. “Your ardent affection is very dear to me. I treasure it and wish you every happiness, with all my heart.”

But in his sorrow Darcy declared, “You are my angel. I will never find another.”

Days passed with Darcy and the vicar at her bedside, each with a broken heart. Cassandra’s passing came as peacefully as one could hope in these cases.

After her funeral, tragedy struck again. The good vicar, distraught over his daughter’s death, succumbed to an apoplectic fit barely a fortnight later. With his passing went the only other person who knew of Darcy’s affair of the heart with Cassandra. He could not bring himself to discuss it with anyone, not even his sister or his good friend Bingley.

Darcy was a broken man. He tried to escape his grief by plunging into the affairs of the estate and seeing to Georgiana’s well-being, but nothing could keep his anguish at bay. The two women he loved with all his heart, his mother—and Cassandra—had departed this life, and with them had gone a part of his heart, a loss never to be recovered.

Then one morning he received a letter from George Wickham, presenting himself for the Kympton living now that the vicar was deceased.

Darcy exploded. The thought of such a dissolute character taking up residence in the place where Darcy had spent so many tender moments struck him as akin to profaning a sacred shrine. Snatching up his pen, he responded with a quick rejection, curt to the point of incivility.

Sir,

I received with some surprise your letter of candidacy for the recently vacated living of Kympton. Perhaps, in the press of business—or the pleasures of the Metropolis—it slipped your memory that you relinquished all claim to preferment in the church for the sum of £3000. I, however, have not forgotten.

Our transaction seems to me more than ample recompense for the benefit my dear father wished to bequeath you. In any case, your manner of living would comport ill with a clergyman’s existence, especially in comparison to the deceased Mr. Graham, a man of God-fearing devotion. I pray you put the notion of the Kympton living from your mind. That holy place is not for you.

Farewell,

Fitzwilliam Darcy

Despite this plain refusal, Wickham maintained a perfect storm of correspondence, reproachfully reminding Darcy of his late father’s fondness, arguing that Darcy had no one else to provide for, pleading the difficulty of his present circumstances, and growing more violent with each succeeding letter.

After turning Wickham’s latest letter into a pile of tatters on the breakfast table, Darcy looked up to catch the expression on his sister’s face. She was staring at him in fright. He spoke to her kindly, calming her, but had to admit that his moodiness was distressing Georgiana.

Perhaps London, with such treasures as the British Museum and the Royal Academy, would be a happier place than Pemberley for her. He discussed the matter with Georgiana’s other guardian, Colonel Fitzwilliam, who readily assented. A respectable lady, a Mrs. Younge, was recommended as the girl’s chaperone, and off Georgiana went.

For months a constant stream of letters kept Darcy apprised of Georgiana’s doings, and as summer drew near, she entreated him to visit her at Ramsgate and enjoy the fresh sea air.

After some weeks, Darcy quit his isolation at Pemberley and went to the resort, to find his sister behaving oddly. When he questioned her closely, she revealed that she had met Mr. Wickham in town. Georgiana had affectionate memories of him, and thanks to his attentions, the fifteen-year-old quickly came to believe herself in love. At length she admitted that she had consented to elope with him in only a few days’ time.

On hearing this, Darcy’s first notion was to seek Wickham at his lodgings and call him out. But cooler considerations prevailed. A duel would make the whole affair public knowledge and damage Georgiana’s good name. Instead, Darcy had to content himself with sending Wickham a sharp, threatening letter.

Wickham quickly left Ramsgate, and Mrs. Younge was soon discharged when Darcy discovered that she had been an accomplice in the elopement plot. A more suitable lady was engaged to preside over Georgiana’s London establishment. But Darcy felt no peace.

By shutting himself up in Pemberley, he had left Georgiana unprotected. What had he been thinking? As her elder brother, charged with deathbed oaths to protect and uphold Georgiana, he had nearly been fatally remiss. Certainly, Cassandra’s loss had been a crushing blow, but to lose himself in sorrow and solitude—that was not the conduct of a Darcy of Pemberley. He shuddered at the ruination Wickham had almost visited upon Georgiana. His was not merely an act of greed for the girl’s fortune, but of malice against the very Darcy name.

Never again, Darcy vowed, would Georgiana be unguarded. He had lost his mother and Cassandra. But he would not be found lacking when it came to Georgiana’s comfort and protection.

Thus he put his grief behind him and left Pemberley to join his sister in London. His days were often spent with Georgiana at lectures and exhibitions. And in the evening there were the entertainments for which London Society was justly famed.

The problem was, Darcy no longer found these diversions to be diverting. His friend Bingley found him at a ball, standing off to one side—alone.

“Come, come,” Bingley said. “This is a ball, not a hanging. You should be dancing, rather than driving everyone to the other side of the room with that face.”

“My expression is merely self-defense,” Darcy replied. “Until your arrival, there was no one here with whom I wished to associate.”

Bingley was reduced to shaking his head. “Perhaps,” he said slowly, “you require a change of scene. As it happens, I am gathering a party to come down to my new place in Hertfordshire. Why do you not accompany us? I have heard that there are numerous handsome ladies in the neighborhood. Perhaps one of them will pique your interest.”

“I think that unlikely,” Darcy said, but he did not voice his real reason. Because none of them can be Cassandra.

Unaware of his friend’s secret pain, Bingley continued to press for his company until Darcy at last consented, though with no great enthusiasm. Oh, he would do his duty someday, marry, and sire a child to continue the Darcy heritage at Pemberley. But, he was sure, none of the Hertfordshire ladies that Bingley extolled would ever stir his heart.

He had loved and lost ... never could he love again.