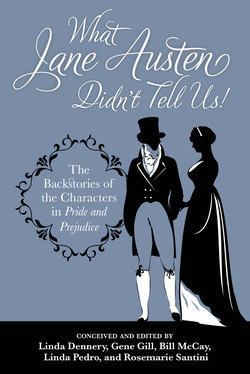

Читать книгу What Jane Austen Didn't Tell Us! - Austen Alliance - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Mr. Bennet by Linda Dennery, Gene Gill, and Linda Pedro

ОглавлениеMr. Bennet was so odd a mixture of quick parts, sarcastic humour, reserve, and caprice, that the experience of three and twenty years had been insufficient to make his wife understand his character.

—Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

“A fine boy!” announced Elsie Kent when she met her friend Mrs. Groggins on her way home from her half-day’s work doing laundry at Longbourn. “Even though Missus ain’t hearty, she birthed a sturdy little lad, and Mr. Bennet was so pleased he treated all the help to seed cake and punch!”

Mrs. Groggins thought that good news, especially the part about the master giving his servants a treat. Everyone knew how eager the Bennets were for an heir to inherit their pretty estate, situated about a mile from the town of Meryton. Heirs were important in Mrs. Groggins’ world, too; they took over the estates that employed her husband, his brothers, and someday in the future, her children.

“And they named the boy Humphrey!” added Elsie as she left, plodding on homeward.

Humphrey Bennet was a bright, serious child. His parents, Elizabeth and her devoted older husband, were proud of their intelligent little boy and determined that he would be well-tutored and well-prepared to assume his responsibilities as the future owner of Longbourn.

Elizabeth taught her son to read and books became a dominant part of his life. Mother and son read aloud to each other, and Humphrey’s imagination was fired by the adventures of Gulliver, Robinson Crusoe, and, of course, Prince Hal.

Although Mr. Bennet was always busy about his responsibilities as a landowner, he made time to show his five-year-old son every acre of Longbourn. He also insisted that Humphrey sit through many of the regular discussions of estate matters that he held with his manager, Schilling.

Mrs. Bennet understood her husband’s eagerness to acquaint his son with the workings of the estate but expressed concern. “Mr. Bennet, I believe Humphrey thinks he is being punished by having to sit through your meetings with Schilling instead of playing in the sunshine as other children do.” In her usual soft, moderating way, she persuaded Mr. Bennet that perhaps he had pushed his son too fast and needed to revise his approach to educating his heir.

The Bennets’ happy idyll came to an end when Elizabeth, always in fragile heath, sickened and died when Humphrey was seven years old. Father and son were both devastated. Mr. Bennet was so racked with grief that he was unable to help with his son’s sorrow. Humphrey ate little and spent every day alone sitting on a fancywork stool in his mother’s parlor rereading the books they had enjoyed together.

One evening at dinner, Mr. Bennet realized that his son had grown wan and listless. He made the effort to talk to Humphrey, but the boy replied in monosyllables and appeared to be trying not to cry.

In consternation he consulted the vicar, who recommended: “The boy should be removed from Longbourn and its sad associations. He needs friends his own age to replace the many hours he spent reading with his mother. Send him away to Harrow School, where he will have to concentrate on his lessons and learn to get along with other boys.”

“It will make a man of him!” appended Mr. Bennet, nodding.

Humphrey in his despair had not the power to object, as long as his mother’s books and the precious footstool came away to school with him. Thus, not yet eight, he found himself for the first time away from the protection of Longbourn and in the company of boys his own age who exhibited all the mischief and untamed pursuits that so fascinate them.

At first, he sat forlorn on the footstool by his bed, reading quietly. Such solitary behavior was inexplicable to his peers who jeered: “Country boy from the shire, do you miss the muck and mire?” But Sir Humphrey Bennet, knight adventurer extraordinaire, rose to the challenge. Armed with his vivid imagination, he devised exotic games and explorations for them that earned their grudging respect. Eventually, he was cajoled into joining in their sport. Humphrey was surprised to find he was beginning to enjoy school!

He returned to Longbourn on holidays, where his father peppered him with sharp questions: “Are your masters pleased? All of them? Do you excel over the other boys?”

Nervously, he offered his response: “I believe, S-Sir, that insofar as I am able to d-determine, I may reply to your q-questions in the affirmative.”

Humphrey found his father’s new censorious manner intimidating. And his parent’s frequent references to the cost of tuition only fed Humphrey’s growing fear that he might fail to fulfill his father’s expectations. Without his mother’s soothing influence, a malaise had descended on Longbourn.

During his second year at Harrow, Humphrey made the acquaintance of Frederick Fielding, an older boy whose home, Netherfield Park, was but three miles from Longbourn. Thereafter, they traveled to and from school together in one of Netherfield’s comfortably outfitted carriages. En route, Humphrey entertained his new friend with stories of dread highwaymen who surely lurked ahead, prompting the compliment, “I say, Bennet, you nearly gave me a fright there!”

During school holidays, the boys rode together daily and soon became fast friends. Humphrey helped Frederick with his Cicero and Freddie taught him fencing and archery. The studious younger boy idolized Fielding, who in turn became his loyal protector.

Excellence at his studies bred in Humphrey a quiet confidence that was startling in the otherwise tentative stripling. His father was gratified by his son’s newfound ease. Yes, he thought, my investment in this public schooling will one day profit Longbourn. It might be well to consider sending Humphrey to University.

Thus, when his studies at Harrow concluded, Humphrey was allowed to join Freddie at Oxford. His Tutors were astonished at the breadth of Humphrey’s reading. He pored over every text they assigned, and more. Freddie, true to his nature and as enthusiastic as ever, introduced the younger boy to other pleasures—drinking and carousing—the idler side of University life.

When Humphrey came down from Oxford, he vexed his father by joining Freddie and his intimates for an extended round of gentlemen’s amusements: the races at Basingstoke and country house visits with their pheasant shoots and riding to hounds. Then they settled in for the London Season at Fielding House, the family’s commodious residence in fashionable Mayfair. Although Humphrey knew his father wanted him home, he was enjoying a young man’s first independence.

The glittering city life was at once dazzling and disconcerting to Humphrey, but he made every effort to keep up with his friend’s set, doing his best to ape their manners and haughty nonchalance. He was astounded but flattered when one of Society’s bright ornaments, the vivacious young widow, Mrs. Meadowes, began to pay particular attention to “Freddie’s young gentleman from the country.”

Only too eager to bask in her smiles and prove his devotion, Humphrey was often seen dancing attendance on the lady, fetching her parcels from the finest shops and warehouses and driving her to afternoon engagements in the most elegant parts of town.

One night, while losing at cards to Freddie’s friends at Boodles, he heard a nearby wag remark: “Our madcap widow is up to her old tricks again. She is doubtless desperate for a new patron now that Sir William cast her aside. She has been setting her lures for a certain ripe squire from the country,” tossing a nod to Freddie’s young shadow, “and I hear he has risen to the bait.”

All eyes turned to Humphrey. He leapt to his feet, wits barely under control. “How dare you cast aspersions upon the honor of an innocent lady? I demand satisfaction, sir!”

Freddie was immediately at his side: “Employ your reason, man! This is madness. Let us leave at once and forget what was said under the ill-considered influence of drink.”

“I will not leave, sir. It is incumbent upon me to defend the lady’s reputation, and I will meet this scoundrel at dawn!”

As his second, Freddie used the few hours left before daybreak to urge his friend to regain command of his temper. He begged him to pay heed to his hurried explanations of dueling etiquette.

Freddie accompanied Humphrey at the appointed time. Pistols were selected, and the men positioned themselves. Following the protocol for minor disagreements, his opponent fired straight into the air. Humphrey, forgetting Freddie’s instruction, took aim and shot his adversary in the forearm. There was now nothing to be done. Freddie angrily pulled his friend away from the bloody scene, bundled him into the carriage, and drove off in disgust.

Humphrey was now a laughingstock among the smart set in London. The young widow’s refusal to see him completed his humiliation. Devastated, he decided to flee wretched London, go far, far away, and never return. A rueful Freddie bade his naïve friend safe travels when later that same week Humphrey departed for the Continent.

Rome was balm for Humphrey’s injured pride. He lost himself in the streets of the sun-filled city, visiting the Colosseum, the Palatine Hill, the imposing new Trevi fountain! The city reignited the passions of happier days at University. Books were once again his refuge. They engaged his intellect but made no demands upon him for action or responsibility. He studied dusty manuscripts in dim libraries and became acquainted with other scholars, but he made no friends.

He tried not to dwell on his London disaster, but when inevitably he did, he reviled Freddie’s haughty friends and heaped sarcasm on his own callow performance: What a bumpkin fool I was! In future, if I face embarrassing or annoying circumstances, I will be the first to render sardonic judgment, he vowed.

After some time he received an urgent letter from his father, bidding him to quit Rome. Mr. Bennet was ailing and demanded that his son return and assume his responsibilities as heir to Longbourn. A chastened Humphrey booked passage home, recollecting how his parent, shocked but uncomplaining, had agreed to a hasty Grand Tour upon learning of his son’s humiliating escapade.

Arriving home, the Prodigal was relieved to find his father’s health improved but still fragile. Mrs. Hill, the housekeeper, ran the house with smooth efficiency, happily requiring no direction from the young master. Humphrey therefore lost no time in commandeering his mother’s shuttered parlor for his own use. That blessed space would become his “library,” a place to hold her books as well as his own—plus those rarities he had shipped home from Rome. He was blithely directing the butler in unpacking crates one morning when his father appeared at the door.

“Humphrey, what do you think you are doing?”

“Setting up my library, sir.

Mr. Bennet dismissed the butler and said: “Good God, I did not send for you to continue your long holiday back here! Longbourn is a large and complex estate and requires your full attention! Stop fiddling with those volumes immediately and assume your obligations as my heir. This you must do, if not for me, then for the benefit of your future sons and all the people who depend upon us!”

Humphrey was mortified: How selfish I have been! I was not summoned home to amuse myself but to relieve my poor father of responsibility for the estate.

In a low voice he asked: “Where would you suggest I begin, Father?”

“Start by meeting with our manager, Schilling. You can trust him; you have known him since you were a lad. But you will soon be master here, and it will be your responsibility to give him direction. Mr. Gardiner in Meryton is our attorney. Pay him a visit. Learn something of the property laws. And for God’s sake, give up this so-called ‘library’ until you have mastered the fundamentals of husbandry!”

Under Schilling’s expert direction, Humphrey began to grasp the tedious details of managing the estate. He was appalled to find their tenants’ disputes dishearteningly repetitious in nature and often not accepting of resolution. Do none of them grasp the simple principles of logic? After several weeks’ determined application to arables and livestock, he paid a call on the attorney, reasoning that the property laws could not possibly be as boring as drainage problems.

Arriving, he was stunned to see the most beautiful young woman he had ever beheld. Mr. Gardiner introduced Jane, his younger daughter, to a bedazzled Humphrey. The enticing Miss Jane dropped a deep curtsey, her abundant enticements felicitously revealed as she sank almost to the floor while murmuring a polite, “How d’ye do, Mr. Bennet?”

Humphrey barely managed, “I am tolerably well, Miss Jane.” His mind was more taken up with the question: Where has this magnificent creature been all my life?

Jane bade Humphrey and her father farewell, saying, “Now that you are home, Mr. Bennet, I hope we will see you at the next Assembly. We ladies always enjoy new partners, especially gentlemen who have a great deal of fascinating conversation.” Then she was gone.

Humphrey was forced to remain behind for the lamentable exigencies of business. How her eyes did look into mine, and with such admiration! What a delightful creature she is!

He left Meryton smiling broadly, blind to the world as he rode slowly home. The substance of his meeting with Mr. Gardiner all but dissolved as he mused over this unexpected encounter with the living Aphrodite. For the first time in years he cursed his abysmal inexperience with the ladies, particularly suitable young ladies.

Cross-questioned about the visit by his father that evening, he waxed eloquent over the charms of the beautiful Miss Jane Gardiner. Mr. Bennet was annoyed that so little actual legal information had been absorbed, but relieved that his son expressed interest in a young woman. He had feared that Humphrey, so solitary and scholarly, at twenty-nine might remain unmarried. Without a Bennet heir, Longbourn, entailed to the male line, would be lost forever to their irritating cousins by the name of Collins.

When the next local Assembly was announced, Humphrey purchased a ticket with great anticipation. Entering the ballroom, he immediately saw Jane Gardiner surrounded by handsome young Militia officers all vying for her attention. But the reigning beauty beckoned him over and whispered, “I hoped you would come, Mr. Bennet, I saved a dance for you!”

What good fortune! When he, a rusty but competent dancer, offered his arm for the Boulanger, he was almost overcome by her assenting smile and eyes that seemed to cast themselves on no one else in the room.

Armed with a modest bouquet of white crocuses, he visited the Gardiner home the very next day. Ushered into the parlor, he was greeted by Mrs. Gardiner who introduced her older daughter, Catherine. Miss Jane greeted him warmly. They sat stiffly. “What lovely spring weather we are having,” Mrs. Gardiner began.

“But the state of the roads is disgraceful after all that rain last week!” helpfully offered Catherine.

“Have the roads dried out yet, Mr. Bennet?” pointedly asked adorable Jane.

Taking a hint from her speaking eyes, Humphrey opined, “By tomorrow the roads will be passable. I wonder if you young ladies would accept my invitation to take a drive?”

Jane and Catherine eagerly accepted.

The outing was a great success. Both young women listened with rapt expressions to his comprehensive history of the countryside through which they passed. Humphrey felt greatly encouraged.

There were family dinners at her house, and walks and carriage rides and another dance or two. Humphrey had completely lost his heart to the lovely, amiably complaisant Miss Jane Gardiner. For the first time, he felt he truly understood the immortal Shakespeare: “She’s beautiful, and therefore to be wooed ...”

His admiration knew no bounds! A month after having met her, Humphrey announced to his father that he intended to ask for Miss Jane Gardiner’s hand. Mr. Bennet was too thankful that Humphrey was finally taking a step toward extending the Bennet line to refuse his blessing. The elder Mr. Bennet never thought to question whether the daughter of a Meryton attorney, especially one so very animated and untutored, was a fit lifelong companion for his son.

So Humphrey carefully memorized several lines from Shakespeare with which to “woo” Miss Jane. He began: “Oh, darling Jane, ‘Hear my soul speak. Of the very instant that I saw you ...’”

His darling giggled entrancingly and kissed him.

After a rather inarticulate confession of his undying love, Humphrey asked if he might approach her father to ask for her hand.

She laughed gaily: “La, Mr. Bennet, you have been so long about it that I feared I would have to accept Lieutenant Jeffreys’s offer. Do, for pity’s sake speak to Papa tonight, for I am all impatience to order my wedding clothes!”

Accompanied as it was by an adoring look, her “intended” scorned to notice his angel’s rather vulgar response. Further quotations from the Immortal Bard now seemed inappropriate as well as unnecessary. Humphrey kissed her soft, flushed cheek: “I will go to him immediately, dearest!”

Mr. Gardiner was pleased to encourage Humphrey’s suit, and marriage articles of £5,000 were arranged.

They were married soon after Jane’s eighteenth birthday and settled at Longbourn to begin the serious business of producing an heir. If Humphrey noticed that his wife was relying heavily on her mother and Mrs. Hill for running the household, he thought it rather clever of that lovely creature to solicit their expert assistance.

Less agreeable was his realization that the new Mrs. Bennet seemed to have lost all interest in hearing him speak of estate matters, the wars with France, or any other significant subjects. He could not help but notice that she tapped her foot when he read aloud the poetry that had “delighted” her just weeks ago—more than once he thought she dozed off during passages he found particularly moving.

And she had found her tongue!

During their courtship she had been pleasingly attentive, speaking typically only to ask his opinion or pay him some compliment. Now she nattered incessantly: “Oh, Mr. Bennet, I saw the most adorable bonnet at the milliner’s, trimmed with little blue feathers! I know you will admire it when I wear it with my blue spencer ... the Gouldings’ ball is next week, and you must be certain the horses are groomed to take us—they looked a little shabby last week when we went to the Longs.”

Endless, empty-headed drivel!

Mr. Bennet Senior took to taking his tea alone in his bedchamber to escape her mindless chatter for at least part of the day. Humphrey began to wonder what kind of bargain he had made.

Just when he was beginning to tire of his bride’s constant prattle, she proudly announced that she was with child. What joy! Both Bennet men now willingly endured her gay, empty babble and frequent complaints of illness. They were nothing to the family’s expectations!

During her confinement, Mr. Bennet Senior weakened alarmingly but clung to life, determined to hold his grandson and namesake in his arms before he died. Alas, after the birth of a lovely little girl, christened Jane, he left them.

Confined to Longbourn during the mourning period, Humphrey returned to his plan for establishing a library. He removed the estate carpenters from their work on the stables to fill his proposed sanctuary with shelves worthy of housing his cherished volumes—and the purchases that were to swell his collection. A special shelf was to be devoted to books that had belonged to his mother. Avidly, he began to read advertisements for book sales and undertook to correspond with select publishers about purchases.

Mrs. Bennet was disagreeably surprised by his taking over the well-positioned parlor: “Oh, Mr. Bennet, I had planned to make this my sitting room because of its lovely view.” She sighed. “Well, I suppose I can make do with that upstairs room at the back of the house.”

Mr. Bennet did not share with her why he had claimed this room for his own, and decided that it was necessary to establish early rules for his refuge: “My dear, since this room will house books which are not to your pleasure but have significant monetary value, I will keep the door closed and require anyone wishing to enter to knock first.”

The year of mourning finally passed, crape and bombazine were packed away. Spirits now lifted, Mrs. Bennet found herself again with child. She presented her husband with another girl. He was pleased to name this daughter Elizabeth in honor of his mother.

But neither Elizabeth nor little Jane could inherit the estate. Mrs. Bennet’s duty not yet done, she was quickly in the breeding way again. And Mr. Bennet once again caught his wife’s happy expectation and certainty of a son and heir.

Sitting in his new library, he reflected: My son will be ambitious, he will take over the work of Longbourn; his enterprise will sweeten his sisters’ dowries and provide the Bennet line with continuity.

This child was a boy, but he was not meant to be, a man-child lost before his time. Humphrey could not forget the bloody, tiny unfinished body he had demanded Mrs. Hill show to him.

All his study of Greek tragedy had not prepared him for the depth of his sorrow, the helplessness that pierced his heart upon viewing that pitiful sight. His wife was in great need of his comfort, but lost as he was in his own mourning, he could offer none.

It was her carelessness that caused this awful loss!

The night of the accident that led to this terrible tragedy haunted him still. When he closed his eyes, he could see his wife, dizzy from too much wine and heavy with child, missing her step and plunging down that flight of stairs. It might be unreasonable, but when Mrs. Bennet reached out to him for comfort, that blame in which he held her surged up to chill his response.

“The less said, the better,” he grimly concluded, priding himself on his silent self-control. Trusting to time to relieve his sorrow, Mr. Bennet sought solace in Milton.

More and more he retreated into his library, where neither wife nor children were allowed without his permission. There, he could conduct the business of the estate, or as little of that business as he could bring himself to face. He never fully lost his distaste for matters agricultural and now trusted Schilling to manage everything. Accepting his employer’s indifference, Schilling involved him as little as possible in the practicalities of running Longbourn.

Mr. Bennet devoted almost all his time to building a respectable collection of books and folios ranging from Alighieri to Voltaire. He found this occupation—adding to his library—brought him immense pleasure.

He continued to perform his marital duty and more little girls appeared: Mary, Kitty, Lydia. With his first two daughters, Mr. Bennet had been an engaged father, drawn to little Jane by her beauty and serenity—so like and unlike her mother—and drawn even more to little Elizabeth by her quick intelligence—so very like his own.

During the first years of his marriage, he had retained hope that the next birth would be the heir. With the loss of his unborn son, he changed. Jane and Elizabeth were still welcome in his company and library, but he resigned the other children to their mother to entertain and educate.

One morning while their youngest child was only a few years out of leading strings, Mrs. Bennet burst into her husband’s library, hysterical. “We are lost, Mr. Bennet! I am quite certain there will be no more children. My time is over. We will never have a son now. We are lost, lost!” She sobbed deeply and moved toward him for consolation.

Humphrey stepped back, inexpressibly shocked. Mrs. Bennet had betrayed him! Longbourn had been in the Bennet family since his father’s grandfather’s time, and now she would deliver it—house, lands, income from crops and rents—to his Collins cousins. The Bennet heritage meant nothing to this silly woman!

“Thank you, Mrs. Bennet, for sharing this important intelligence.” Backing still farther away, “I have much to do today, my dear. I am quite busy. You will please close the door as you leave.”

When she was gone, Humphrey sat at his writing table with his head in his hands and wept.

I have betrayed my solemn trust ... I was a fool to marry an empty-headed woman ... unable to provide Longbourn with an heir! Unable to provide me with companionship!

He looked around his library, his sanctuary, and for the first time perceived not the books but his own culpability.

These volumes reproach me. Surely I could have devised a way to provide for my poor girls. Purchasing books to entertain only myself rather than saving to enrich their dowries! What a fraud I am—neither scholar nor father—and it is too late to amend the situation.

“Aye, ’tis many a good hanging prevents a bad marriage.”

Mr. Bennet’s epiphany faded into the empty silence that followed this outburst. His composure returned with the recollection of his own robust health: I will not be dying anytime soon. Our girls are safe enough ... Was that the butler announcing dinner?

But his equanimity was short-lived. No sooner did he exit the library than his wife accosted him. “Mr. Bennet, my nerves are destroyed when I think of that terrible entail and our girls being forced from the only home they have ever known by your odious relatives. What will the neighbors think? What of the feelings of our servants and tenants when they see their mistresses treated so rudely?”

“In that unlikely event, Madam, it gives me great comfort to know our girls will surely be the handsomest and best dressed women ever turned out into the streets.” And with that sarcastic reply, she had to content herself.

Poor Mrs. Bennet. Her one tragic impropriety served as justification for her husband’s every excuse to do nothing.

Some time thereafter Mr. Bennet received a letter from Mr. Christopher, a dealer in rare books and manuscripts who had supplied some of the volumes in his library. The dealer asked to call on Mr. Bennet the following week when he would be in the vicinity. Humphrey assumed Christopher had a prize manuscript for sale, and reflected ruefully that he had only scant funds available for new acquisitions. Thus he was surprised when the book dealer arrived and after looking around the Longbourn library and some polite small talk began:

“Mr. Bennet, I am delighted to see your entire collection—very fine, sir, very fine. One of the most impressive small personal libraries it has been my pleasure to see. I had no idea you had acquired these rare incunabulae! Such early examples! Your taste is superb and reflects a genuine respect for and understanding of the printed word!”

Humphrey smiled, pleased with this expert’s opinion of his collection.

Christopher continued: “I have a client who, having inherited a large fortune, has purchased a country home with an empty library room that he is eager to fill. In effect, he wishes to obtain a collection of volumes to furnish his bare shelves.”

Humphrey thought: How delightful to be able to purchase many volumes at once, but how sad to deny oneself the pleasure of acquiring each volume. He could not envy the would-be collector.

“Not to put too fine a point to it, Mr. Bennet, would you be willing to sell your entire collection to equip his book room? The buyer has authorized me to purchase such a library at a considerable sum. As his agent, I would make all arrangements for relocating the volumes, and collect my agent’s commission from him—There would be no trouble or expense on your part.” Humphrey was immensely flattered, and tempted—The sum mentioned would certainly enhance the dowries of his five daughters! But to give up his precious library where each volume had been so carefully selected over more than two decades?

Never!

I have put my heart as well as my intellect into this collection. It has been my consolation for an unfortunate marriage and the lack of an heir. He declined Mr. Christopher’s offer and made no mention of it to Mrs. Bennet.

* * *

Mr. Bennet rarely took up his pen, but occasionally roused himself to attend to correspondence with his oldest friend, Frederick Fielding.

Letters from Freddie, outrageous as ever, could always provoke a smile. In his last communication he had written some amusing nonsense about Humphrey permitting him to introduce:

whichever of your ten daughters is “out” to the eligible Baron Kreutzer who is actually making his bow at Almack’s! True, his debts are alarming, but the title alone makes him as fine a fellow as even you could want when he is sober!

Reading this, Humphrey laughed aloud! But perusing further, he found the letter continued with some actual news:

Now that Mother is residing in Bath, and having no taste for country life myself, I have let Netherfield Park to a single young gentleman of good fortune from the North whom I think will prove interesting, both to yourself and your daughters.

Mr. Bennet frowned. His wife would soon hear of a well-bred, cultivated young man moving into the neighborhood and see him as a heaven-sent marital prospect. Doubtless she would then commence a relentless campaign to gain an introduction.

Reflecting that engaging this Mr. Bingley in polite conversation was unlikely to be half so amusing as vexing his wife by not mentioning the visit, Mr. Bennet rode to Netherfield to meet his new neighbor directly.