Читать книгу HAMMER! - Barbara Hammer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMy Life as Henry Miller

I WAS SITTING ON THE KITCHEN COUNTER WITH ONE leg dangling. Across from me, cross-legged on the floor, sat a young woman with short hair wearing an Army fatigue shirt. Gathered around were others of the Santa Rosa Women’s Liberation Front’s Guerrilla Action Theater. We were planning our next action, a confrontation with a local woman journalist who had plagued us with her derogatory writings. We would meet her at her home and have it out in her rosewood living room on the hook rug. Diane looked up at me, raising her head so that I could just see her beautiful brown eyes beneath the shock of bangs. Her mouth twisted as if she were going to lay a trip.

“There’s something I think you should know.” She had the cutest impish grin on her face, real seductive-like.

“I’m gay.”

My attention focused on her and I could feel my body lean forward as I concentrated on this information. My tongue had the feel of orange peel. My mind went in circles trying to find a holdfast, some escaped knowledge code of the past. What did it mean to be gay? I had no idea, and my white, Protestant, middle-class background hung in shreds from my shoulders, leaving me without the least protection. There was nothing to do but admit my stupidity.

“What does that mean?”

With a straightforward attitude and no trip attached Diane began her explanation.

“It means I love women, and that my energies, time, and affection are given to one particular woman.”

Goddess I was curious! I felt like I was on the track of some hot scent. My ears felt like cauliflowers, I was straining so hard to catch the significance of every word.

“Is that the woman you’re living with?” I asked like a dumb cluck. My fantasies rose like winged mirrors before my eyes as I wondered what they did together.

“Yes.”

“Well,” I stumbled, “how can you get it on?” I was so inept.

“I follow my feelings. It’s not that I don’t like men, it’s that they don’t do anything for me, if you know what I mean.”

Did I! Hmm, I was thinking, this is a new element entering my world. I definitely cannot deny my interest. Look at me, I’m about ready to fall off the counter into the poor woman’s lap. This wasn’t the time or place, and my “good senses,” those that were socially trained, helped me to return the conversation to the guerrilla tactics to be used on the journalist.

As the weeks went by I noticed that Diane never came to meetings with her womanfriend. I asked Kate, who generally seemed to know a little about every one of us and who was somewhat of the central organizing figure, as much as anyone can be in a leaderless group. She seemed quite protective toward Diane and took me aside to share some special information.

“Diane’s really getting it on with us in the group and that wouldn’t be the case if Tove were around.”

“Tove,” the name was mentioned. I was transfixed. What power could this woman hold over another? Especially another such as Diane, who was so perky and independent-minded? Does she hit her over the head, I wondered; does she sit on her chest to prevent her breathing? It had only been three months since I’d been out of an oppressive marriage, yet here I was acting as if I didn’t understand. The problem was that I had never considered the ability or possibility of women sitting on women, keeping them down.

“How do you know this?” I asked.

She looked very correct and self-assured when she answered.

“Because that’s what Diane says.”

From that moment I became even more curious about this relationship. I told Diane that I would like to meet Tove. One time I called Diane up about a meeting and Tove answered the phone. Her voice was husky and warm. She had been working on a motorcycle, she explained. Well, we had something in common, for I’d long been a motorcycle fancier. Would she take me for a ride? Sure, she responded, in fact, next Wednesday she’d pick me up and drive me to the meeting.

“Are you going?” I asked with what probably sounded like amazement.

“Yeah, there’s a lot of shit going down about me and I want to get it cleared up, so I’m meeting with Kate and some others before the meeting so they can say whatever they have to say straight to my face.”

“That’s a good idea,” I responded, never liking back-talking among sisters.

I had seen her from a distance in the women’s class sitting next to Diane on the floor, but outside of the fact that I knew she was dark-haired, I had no idea what she looked like. There she was coming up the driveway, parking the red bike, taking off the helmet that made her look like any other catcher in a ballpark. Yes, her hair was dark. She was pushing open the screen door. Her cowboy boots added impetuous inches to her height. Her nose jaunted up in the air like a proud lady, and her eyes flashed when she saw me and said, “Hi.” She was wearing a dull black turtleneck sweatshirt, the kind that loses its sharp edge and fades into a comfy-looking, soft-wearing shirt. Her nipples were there. Standing right out in front of her and I could tell her breasts wanted to be gathered by hand. I am flustered. I make noises about changing clothes and run upstairs and change twice or three times before I can be satisfied. She waits. Finally, hips hugging the black leather seat, arms around Tove, the wind blowing the city sludge away, I look up at the branch patterns floating by and let everything go. We take the back way to the meeting, round and down the old farm road where the breezes are scented with ripe hay and turned earth. She is a careful driver and takes the curves with ease. Impulsively, she turns into a cemetery, and we stop to talk among the gravestones and irises, as was to be our fashion—though little did we know it then—for the next two years. The sun was setting. The vista and aromas were pleasant, but the impatient, entangling women were calling. We couldn’t be too late for this important meeting.

I wait outside, walking through the empty lot’s high yellow grass with Kate’s son while the others rap inside. When I enter the house for dinner all is quiet and a little strained as we sit munching around the PG&E wooden-spool table low to the floor. Later, I ask Tove what happened.

“Nothing, the cowards were too scared to talk.”

“But didn’t you bring it up?”

“I tried to but they wouldn’t have it.”

We stand in line next to each other laughing and talking. I am with Donna, and Tove and Diane are ahead of us. We buy our tickets and sit down. The lights dim in the theater and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest starts flying. My knee is accidentally touching Tove’s, and I do not move it away. It stays there through the first two acts. At intermission we share a joint. Back to the seats. Her knee is conveniently free and I let mine slip over and be a part of her presence. Again, hers doesn’t move. I feel a passionate rush spread through my body and I recognize it for what it is. I sit and think. I am sexually aroused by this woman. I can ignore it and deny something that is a part of me and let it slip into herstory that won’t be told, or . . . Since I’d learned about Gestalt and Laing, and since I’d been in an encounter group and read a lot about getting in touch with feelings, it wasn’t difficult to decide then and there that I would admit to my emotions, and if the time came, I would follow them.

She slipped into bed beside me. Diane was on the other side reading a book, and didn’t want to be bothered with our feelings. I reached my leg out so that it was touching hers. I felt the same surge as I did that night watching the play. Could she care? Could she feel like me? I was too timid to ask, and lay there in my trained role of heterosexual countermate, passive female. Her hands began to touch parts of my body. Diane got up from the bed and went into the next room with her book. I scarcely noticed; I was responding by doing what was done to me. I touched her skin. It was soft! My Goddess it was soft! Not like the terribly thick and hairy skin of my ex-husband. Then and there I think I became committed to women’s liberation in an entirely new way. I had been denied the freedom of touching another woman warmly and intimately all these years because of heterosexual bias that had been fed to me, and that I gurgled up along with bottled milk and toilet training and table manners. Goddess what a product I was. Put in and you will get out. That’s how ma and pa made me. I can’t say all that was going through my head right then and there, for there wasn’t anything separating our total quivering, pulsing bodies together. Red and jelly-like, I could have been squashed that minute. I was without defense, without societal armor. I was clean and fairylike and we were children again! And on and on until the sun came through that upstairs window. I can remember it still: her knee pressing, her thigh pressing, our bodies burning like hot fires. She stroked my face, pulling the tired strands of hair away from my forehead, pulling at their roots, telling them to let me free. Her stroke was the touch of a Florence Nightingale, a primeval mother lover. Nothing lay between us, for me no unresolved old loves, no future promises. It was fresh and new and I was responding to the hot branding iron of her hand that smoldered my skin wherever it touched. So went our night. Ending and beginning again for me the first of a long succession of satisfying climaxes and tender closeness I had never known with any other lover.

My job was finishing the next day, my rent was up, I was recently divorced and without a new set of friends; generally I was at loose ends without plans for myself, and when Tove suggested I move into the house with her and Diane, I accepted. This was a primary mistake for the relationship that would develop, based on my dependency on Tove rather than on a fiftyfifty, independent female to independent female friendship of love and respect.

Tove and I were lying in the back room on her bed, watching the morning sky brighten through the Petaluma fog. Our covers were thrown back and we lay like our comfy cats, Foggy and Luce, in each other’s arms. It was the time before ambition to rise and start the coffee, the sweet time when bird songs are heard, the time when light on the wall is noticed, the time before the busy activity of the day dulls the child’s perception in us. Tove would get up in a minute, her crumpled brown hair matted, and groggily stomp into the kitchen to plug in the coffeepot. She’d dress, eat, leave a warm note for me, and be off to school. There was a knock near the open door. I saw Diane.

“May I come in? I want to talk with you Tove. Privately.”

“Hurry then, ’cause its getting late for me.”

I left for my room. I could hear them through the unclosed doorways.

“Why wouldn’t you fuck me last night?” Diane screamed.

“Because I didn’t feel like it,” Tove answered.

“Well it was the least you could do for an old friend.”

“I can’t do it when I don’t feel like it.”

“You masturbate Foggy, why not me? I was horny.”

There was a long pause and I didn’t hear anymore. I peered into the room. There was Tove standing naked, back tense, looking in her stiffness like Napoleon. Diane was sitting on the bedsheets. She looked desperate. As Tove turned, I stepped back into my room and watched her march as if she were wearing stomping boots out of the room and down the hall.

There was a lot of screaming and tenseness those first few weeks before Diane left. I kept out of it, although I thought I had something to do with precipitating the quarrels. Tove said that resentments had built up between them for the last two years. Problems from Diane’s dependency on her, and her allowing it. I was embarrassed by quarreling, a fact that grew out of my girlhood. When my parents had outrageous arguments I would listen at the door with a mixture of curiosity and terror. I would promise some unknown God he could do anything he wanted with me if he would only stop my mother and father from fighting. It was a mistake. Praying to a man never did any good.

The worms were another problem. Diane and Tove had purchased together ten wooden bins of red earthworms. These sat in our front yard behind the goat’s pen. The business never got started, as the women were too busy arguing how to advertise the bait. What to do with the worms now that Diane was moving out became the central issue replacing sex. Finally a man came and bought the worms. Diane moved out. Tove and I were alone in the house. Alone in the house. Alone in the house. It sounded so ominous. And it was. As a married woman, I found the house to be the cage of my oppressor. Lesbians, womenidentified women, could and would not, in my mind, become oppressors of each other. How wrong and foolish I was. How capable I was of falling into the victim role again. She went off to work in the morning after her coffee, leaving me notes under the iron, behind the dish soap, stuffed in the cavity of a sponge. Little love notes, sweet words printed on hard-boiled eggs. Words of endearment, letters of enchantment: she let me know I was on her mind. How wonderful and how beautiful she was! Still she was engaged in the community, her teaching job providing her with the external feedback outside the nuclei household an individual needs. I struggled along, the supported artist, writing poems to her each day, sometimes performing enormously angry and frantic artistic gestures of proof and power. One day I put on a doctor’s white cloak and moved all the furniture away from one of the walls in the living room. I stapled plastic Visqueen from one end of the room to the other. I spelled out the words “Let’s Make It Tonight, Baby!” in masking tape. I placed a wire cage next to the writing. I sat down on the floor, leaned back and became part of the work. I had my picture taken. I was being as freaky as needed to make my statement. I was acting out my urges in the male-defined art movement style of abstract expressionism, gesture painting, gesture. I spent no time analyzing or objectively criticizing my work. It existed and therefore it was. This blind faith in imagination before all led to obscurity and incoherence. Eventually it led to my doubting myself and then doubting my doubts. Women’s criticism—the advice given me in small group meetings—helped change that.

“We can’t understand you when you speak abstractly.”

“Describe what you mean using personal experience.”

“Talk simply.”

Tove would come home from work and we would take turns providing each other with Safeway steaks or boot-legged wine ripped off in the latest fashion. Foolhardy, headstrong days of invincibility, when I would come out from the store with two bottles of expensive wine down my jeans held by my waistband and a bottle of brandy tight under my coat beneath my arm. How I dreaded the crash of a slip! We ate and dined well and continued our guerilla actions clandestinely. Sexist billboards using women’s bodies for commercial purposes were Xed out with red spray paint; “Pretty Bodies Buy Milk” was smudged so that it was unreadable. One night we parked my VW down a side street and walked to the highway, where we hoisted one of us up to the billboard runner. Then between headlight flashes we zipped on the spray. Another night we got back at the round aluminum milk trucks with their offensive advertising by rapidly running with the paint cans along the truck, then ducking between tanks when cars came by. With our motorcycle trip to Washington and these small acts of protest our feelings of strength, health, vitality, and right-on-ness developed through action.

THE MOTORCYCLE TRIP CEMENTED OUR TOGETHERNESS. We found we could operate in and on the outside world effectively. We could drive, we could camp, we could tune up our bikes. We slept at night by rivers or in pasturelands. Once we were refused service in an Oregon restaurant that had a sign posted on the door, WE DO NOT SERVE HIPPIES; another time I was issued directions at a service station by a grouchy male attendant. The world was peripherally hostile but we held our own, hugging and snuggling like great blue caterpillars in our sleeping bags as the sun went down evening come evening. It was wonderful, and we were big and brave and capable women. So when I left for Europe soon after, in what I thought to be the same spirit of adventure, I didn’t know I was running away from lesbianism and Tove.

Six weeks of solitary travel in the British Isles; six weeks alone, more alone than the equal amount of time I’d spent in Mexico as a married woman the year before. Six weeks of youth hostels, of bedding down with all the lovely bodies stripping and giggling in the washroom of the dormitory. Six weeks of long letters to Tove, and too, of exhilarated times when solitude heightens emotional intensity. Most vividly, the ten-mile walk I took around the Northern tip of Ireland, the Giant’s Causeway of dolomite octagonal pillars that stretched into the sea, and finding natural geographical earthworks in every ravine. Walking, alone with the wind-whipped rush of blood to my cheeks, I felt the thrill of discovery as if I were the first woman to come upon such scope and wonder. At times, alone in bed at night, I was able to admit I was avoiding Tove and our deepening relationship by taking off alone.

Then she was there; she was walking through the glass door of the London Youth Hostel. Her hair was shorter than I remembered, her walk jauntier. The red parka set off her cheeks and I had a womanfriend again! A gesture, a hug, a kiss that covered centuries, a Cognac-influenced talk that became less coherent and more warm as we made one bed out of two mattresses. The shock of the hostel matron when she found us an hour later smooching lustily! The obscenity of her orders returning us to assigned beds and places! Our junking of the rules and making it together in a narrow bottom bunk in a room of other ladies with choked cries and near-silent whispers! The giggles of the women in the morning when they woke and discovered our double bulge where a single hump should be! The walk down London streets with the glaze of fatigue and solitary travel stripped from my eyes by the fresh wonder of a woman walking outside her culture for the first time!

Two lesbian women outside their culture and without a community. It risked our love. We fell into dependency that began to tie our individual and unique spirits like knots in lagging muscles. We lived so close and so tight to each other those two years without any other significant persons, without a group of friends or even acquaintances. Then the growth of decay from our strangled affair began, and we didn’t see it until it was too late. We had too many hurts and established too many painful habits of relating that became the system we both wanted to tear down. We returned to the States in the fall of 1972 and went in separate directions. She stayed in a valley community upstate to pursue her career in botany while I enrolled in a San Francisco college to study filmmaking.

San Francisco State University was in a state of administrative repression of student initiative under President S. I. Hayakawa, for fear that another mass strike, similar to the faculty and student protest during 1968–69, might reoccur. Out of curiosity, I went to the Women’s Alliance, a loosely formed group of faculty and students who came together twice monthly to discuss feminist issues. I became involved in an attempt to form a women’s studies department on campus and met with resistance from both faculty and students who didn’t see the need of seeking a base of power, and who feared departmental rigidity and hierarchical authority lines developing. After a semester’s effort of energy-draining, resultless political activity, I withdrew in dismay and exasperation to concentrate on filmmaking. I was still lonely and without a love relationship in my new community.

Her face was round and oval at the same time. Her cheekbones were high like an Indian’s. She had the Danish blush of summer on her cheeks. Her eyes were blue, clear, and twinkly. She was young with humor. Her laughter restored me, for I laughed with her. She was tall and strong and capable, and she was twenty-one. My age bias slipped away. She used her hip like a knuckle bone massaging my pelvis, and the bed spun round, dizzy circles of gibberish and giggles the night through. How fresh and revitalizing. My empty body sucked in nurture. She refilled and made me young and forgetful of myself in our few days together. I skipped when I walked; my classmates found me friendly. My distance shattered. I was as close as two tender blades of grass with her. Then she was gone. Like the sun on a rainy Frisco day, gone. She wasn’t there. And I searched and I asked but the replies were not about me or us but her confused sexuality, her alienation from too many affairs. I was left, an empty whistle.

Far worse was the fight to leave the wedding band of monogamy with Tove. This second love with a woman I kept secret from her. I lied until it was over and then I told her what had happened. She was hurt, her expectation of my honesty blown. I was cruel with her. I yelled my freedom and forgot hers. I was mostly and unfortunately unable to feel love for more than one woman at a time, and when I was with the young lady who could throw a baseball like a bullet I was mean and distant with Tove. How fucked it was! I could rap for days about non-monogamy and be completely and emotionally incapable of generous love.

In Los Angeles, where I had gone in January to settle the affairs of my mother, who had recently died from cancer, I met Pat. I was living alone, and finally as business matters were coming to a close I had a chance to do something for myself. A women’s art gallery was opening in Venice. Without a second thought I was in the car and off. The place was jammed, crowded with women and men obscuring the works of sculpture and painting with their live bodies. A perky red-haired woman with a pixie cut approached me. She was wearing a matching purple outfit and looked the Los Angeles style I had left years ago. She was fascinated by artists. I felt I was the admired and she the admirer. We joined a group for pizza and she mentioned a gay bar over dinner. My alert interest matched hers and we established then and there who we were. After driving through the darkened Hollywood Hills, parking in an unlit alleyway, stepping out of our respective cars, walking to the side entrance, we reached Mandrake’s.

“I’ve been looking for a place like this all week,” I tell her. Pat puts her hand in mine, squeezes it saying, “Oh, Baby, if I’d only known.” Again, I was being rescued and carried into love on a white mare’s charge. The romantic conception was thick with layers of myth, although Pat stood a slight five-two. Those words, that squeeze, satisfied my need. I was lonely, depressed from the trauma death brings in our culture to those who live beside it for a while, and here I was promised a friend. We danced with the changing star-dots of light, mingling with a weird crowd of men and women with dyed hair, an LA scene foreign to my honkeytonk San Francisco.

She mixed me a gin and tonic as I popped out my contacts and ran the water in the shower. One drink now amid the peals of strung-out water drops shooting down my back, and one later placed beside the queen-sized bed, spread and clean sheet pulled back, all ready-like. I was rolling over and feeling the freshness of the linen with the freshness of my body. I changed the radio station to classical music from the crooney notes of the 50s Pat had chosen. I sipped my drink. She came in and lay down and we were carefully pulling each others pubic hairs, exploring. Hers were fine and red, truly beautiful. She made me feel comfortable and at home. She smoothed the discrepancies with gin and a stroke of her hand.

The hairs on my arm stood up. It was as if there were electric friction between the near noticeable pressure of her hand, as soft as a flea, and the unnoticeable, until now, body hairs of mine. We made graceful and wonderful love together for the next four or five days in bed. It was one of those times you don’t want to get up.

By then I was beginning to know that Pat wanted more stability than one night stands in her life, and that I was a possible leading character in the play she wanted to write of settling down and homing it. I told her of my naiveté, my beginnings of exploration in lesbian culture, my curiosities, my belief in non-monogamy. She said something that has never been a compliment by any means in my mind: “I guess you have your wild oats to sow.” Her conception of sex and my own were fields apart. I wanted to believe I was planting and nurturing love among women, not employing the love ’em and leave ’em tactics of a coarse and unfeeling male. With my good intentions feeding me, I called Tove long distance to be honest. The cost of that phone bill attests to the fact that non-monogamy was no easy state for her to accept. Pat would be driving up with me to San Francisco and Tove would come down from the valley and meet her. Sixty dollars later, that was settled.

Tove was waiting outside my sister’s house in Berkeley. She had the look of a cornered hare on her face. She seemed shattered, hostile, and defensive. She refused to come in and join us. Another nasty man had given her hell in her hitchhike down to see us. I couldn’t blame her for her outrage, which had extended to include me and the world by now. She wouldn’t come in and she wouldn’t speak to that woman! Her face was a pout I cajoled and tickled and finally, I kissed. She relented. Pat was rocking in a rocking chair. I introduced them. They rapped. I left them alone, unable to participate in their introductory words. What a goof-up I was. Just what I wanted, two lovers relating, and I was running from the act like a scared fish. This was incredible. I obviously had trouble living my ideals. I was a radical who had lost touch with the physical world; my body was nineteenth century and my ideas were running in lap with the twentieth and twenty-first. Nevertheless, I was determined to try.

That evening the three of us lay out mattresses in the basement where I was spending the last night of rent. We had moved my stuff already, and it was near-empty. We made our bed with sleeping bags unzipped and lay down with me in the middle, Pat to my right, and Tove to my left. The electricity that passed between Pat and me must have freaked Tove, for she crawled out sobbing and went to the next room, where she lay on a half-stuffed laundry bag of dirty clothes and cried. I left the makeshift bed since no one was sleeping or using it for any purpose—and went to comfort Tove. When a sister is crying there is no need larger than her comfort. Slowly I reassured Tove that she wasn’t being replaced by Pat, that she had a special place with me. We went to sleep.

As if I could learn from one night’s experience! The next evening, laying out the mattresses, this time in the new house of feminist therapists, and in the living room, no less, since my new room hadn’t yet been vacated, we snuggled down for the night like three lambs, me in the middle again: uncomfortable, but hopeful.

As I drove Pat to the airport the next day she called me selfish and inconsiderate, a real egotist. I sought pleasure for my own ends and hadn’t included her. I couldn’t hear a word she was saying; I justified my sex with Tove as natural and said I couldn’t help it if I were turned on to only one person at a time. But I hadn’t let myself go, let myself be free to love two at the same time; I had reverted to the old and familiar habit of the subject-object sentence pattern, life pattern. You could diagram it, the patterned behavior, it was so simple. I hadn’t expanded my life form one bit by excluding her. I was an isolate, an egoist, and for me, life did center around my needs. I had never lived any other way. Was I capable of change?

She sat in the passenger seat with her head staring directly into my face which was concentrated on driving.

“I think you are very selfish,” she reiterated; her red head and her tight red face made me see she was very serious. “I feel like you and Tove were using me so you could get it on,” her lips were drawn together and cracking with pressure. “I don’t want anything to do with you anymore.” Her face was impossible.

Pat and I failed to work it out, and although she promised me a second chance over a Bloody Mary in the airport cocktail lounge before she left, we never got it on again. The next time I saw her was at the Lesbian Conference in Los Angeles. We started out on rather bad terms; she had promised to put two of my paintings in the art show, and I had given her the dimensions so she could save space. She didn’t save any space for them or me, and I wondered then if this was a petty way of getting back at me. For sure I was angry, for I had gone to some trouble to transport two canvases down in the backseat of my car. Given the chance, one of them would have been the scandal of the show, if art can be a scandal in the lesbian community. When I saw Pat at the bar in Hollywood and suggested we get together again she said she would think it over, then told me fifteen minutes later that she’d rather not.

I WAS SEXIST. THERE WAS NO ANSWERING BUT YES TO that charge. The second night in the new house with Tove I left her sleeping in the living room and went to the “therapy room to smoke a joint, watch a late night TV show, and talk Spanish, generally getting it on with an attractive Costa Rican woman, a psychologist from Illinois, a woman of extra-sensory perception, a distraught and brilliant woman. Patience is the only person I know who can stay in a bad situation and let it remain just as bad for the longest time.

“Yo quiero ir a Costa Rica y generalmente, La America Central.”

“Está muy bonita; hay muchas montañas y la compaña es verde. En verano hay lluvias pequeñas pero muy fuerte. Visité hace dos años mi casa. Mi madre es muy seductiva. Es mala por mí, she spoke in rapid Spanish and I was just able to catch the gist of it.

She was sitting across from me with her legs stretched out on the wooden PG&E spool that yet again served as another lesbian kitchen table. I felt our closeness had already been established, yet she was holding back somewhere and for some reason, that way people do who are slow to warm.

“You know there is a certain point past which I will not go,” she said, “and furthermore, I think there is something in your head that isn’t in mine. Would you tell me what you have been thinking but not saying?” she asked with a smirk.

My confessionary self would not hold back in response to the therapist. Although she said later she did not want to be my therapist, but my friend, I doubted that she could separate one part of her life from another.

“I was thinking about how attracted I am to you, how fresh and enthusiastic I feel, how passionate, how I am feeling like making love to you,” I told her directly, at the same time heading toward the door. That ambivalence of words and action was to become the center of the relationship that developed between Patience and myself.

The next night we went to a quiet bar. I held her hand and looked intently at her across our drinks. I confided. Her face was impassive, and though she held my hand, it was with clearly drawn distance. That night as we entered our house I told her of the fire she started in me, and what a difficult time I had sleeping as I was awake for hours thinking of her.

“You can’t push a river,” she responded. I wondered, did that mean her flow was intense and we would arrive at the source together? Did that mean she was sluggish like the Missouri and would take a long time coming? I thought of hydraulic dams and the massing of power; I thought of the dynamo and the virgin. Finally, I understood. This feminine consciousness was one of flow, and my eager attempt to rush things was out of place.

A week later while I was preparing dinner for the four of us in the house she came into the kitchen, leaned back against the stove, and asked how I was.

“As good as one can be who is frustrated.”

Her manner was serious, as though she’d been thinking of changes.

“I have decided we should sleep together. That is best. So now you can stop being frustrated and know that the next time there is a chance we will take advantage of it.” She said it to me as though she was conducting a business meeting.

I was dumbfounded. Just like that! Rationality and planning in matters of love had not been my forte, but I accepted answering her cool, brash manner with my own.

“Fine, I’m glad to hear about it, and you can count on it that I will be ready.”

I don’t know exactly when it was after that, but we were in bed shortly. The moon was full and beaming through her window. She lay on my breasts supported by one arm and stared and stared at me. We would kiss and touch and then she would look at me again. That went on all night without our total involvement. Her moonlit face appeared and reappeared during my school day, in the middle of a speech I was making in a seminar, or while I was walking across campus. The face was ashen grey and serious. The eyes were questioning. The dark hair framed an oval face of immense complexity and insecurity. The faint mustache on her upper lip echoed a trace of the intent dark brows. What any of her looks meant I didn’t know, and was too frightened to ask. Frightened because this relationship was so tenuous and dependent on her will that I couldn’t move in any direction.

One night, in the midst of an embrace, I thought I heard her say, “Move away.” I did.

“Why did you move away?” she asked.

“Because you asked me to.”

At this she broke out laughing, as was her way. I was a source of amusement to her with my blundering.

“You’re crazy,” she laughed.

“I am not. I heard you say it,” I proclaimed, wondering whether I had or not.

“You’re projecting,” I tried.

She only laughed harder, convinced that I was the loonier of us.

After that, although Patience and I slept together several times, we never got it on. I was confused by the attraction-rejection syndrome I continually reenacted with her. She had hurt me once by admitting to not wanting to go with me to a show, and I had foolishly wanted her company enough not to leave the spoiled child home. We were on our way, of all things, to see male-made, heterosexual rapist pornography in the form of a movie that I was to criticize in a public panel. By the time we were seated in the audience made up of well-suited business-type men, Patience had forgotten that she hadn’t wanted to come. She made gross and apt comments in my ear on content and meaning and reason, telling me she could not get it on with a man for the next five years because of this movie. I was stifling laughter and trying to write down her comments as fast as I could in the dark theater. When the final, slow-motion ejaculation came on in great flinging wonder we were both nearly sick. A woman’s mouth lay horizontal in the screen eager for the catch. Gag. What a place to take a ladyfriend.

A strange thing, the attraction between us. It did not exist genitally. We didn’t trust each other enough to give ourselves the freedom to relax and let go in a sexual relationship. It was doomed to constriction, although we made half-hearted attempts at loving. I eventually moved out of the house, which was becoming a bad dream for me. Patience made me promise I would keep in touch by phone, although for weeks she didn’t seem to find time to call me. I should have known then that the end, which never developed a beginning, was in sight. I would call her from Janice’s apartment house in downtown San Francisco where I was living out the last few weeks of the semester. Sometimes she would talk to me and sometimes not. I knew the protective language the other women in the house were trained to use.

“Patience’s not here.”

“She’s sleeping right now.”

“Sorry but she’s not in.”

“She doesn’t want to talk to you.” Finally.

The list hadn’t changed since I’d lived there and heard these responses to her other suitors. This time it was me who got the cold receiver’s message. One Monday she granted me a visit. It had been a month since we’d seen each other. I waited on the front porch for her and followed her into the familiar kitchen where the cupboards were made from packing crates, and she poured me out half a water glass of vodka and ordered me to drink it to catch up with her. I told her I wasn’t in the mood for drinking but would have a regular drink. She served me insolently.

“I supposed you’d like mix and ice too?”

“Yes, if you have it; at least, ice.”

I followed her into the living room where we lay down on floor cushions and tried to catch up on our lives.

“I am in great pain. You must know that because you have the same pain in your confusion over Tove,” she told me. I couldn’t relate to what she was saying, for when I wasn’t with Tove I wasn’t thinking about her and wasn’t having any pain. My pain lately had been from not having a good and honest and satisfying relationship with any of my womanfriends. But she didn’t believe me.

Later I followed her into her bedroom and we lay down on her foam mattress. She covered her eyes with her forearm as if the world were too much. I wanted to comfort her. She told me to go, that she had no room for me tonight. That she could think of nothing else but her problems, and that it wouldn’t help to talk about them with me. She led me to the front door nearly two hours after I’d arrived. Her eyes were blurred and she had achieved the blank distance she’d sought with alcohol. I was thankful I hadn’t drunk enough to affect my demeanor and I felt capable and competent in leaving this one to her private solace, may she find it. Still before I left she made me promise to phone her.

About a week later I did. We made plans to go to Mount Tamalpais on a motorcycle ride. I felt like consoling her or at least doing something for her that would show I was a friend. Taking her on an outing into nature was my way. I arrived a little late. She had been waiting and was ready to go. Her face looked blank and distant again as if she’d prepared herself for me. We bundled up and drove off over the Golden Gate. She was happy with the cold wind biting her barbituated cheeks. She said she was so comfortable she could fall asleep. I hoped she would hold on. Turn after turn we were curving up the mountain, and I was taking too many chances at passing cars. Patience brought out the risk-taking part of me.

Walking through the park she became perky and alive. She felt she knew where the trail lay, but she led us in the wrong direction. She was solaced by the vista of mountain meadows, the trees. We walked past the amphitheater where I promised to perform later and found a private manzanita glen where we could look out over the suburban hill residences of Marin County, the bridges, the strange white square homes of the city dwellers. Looking back on where we came, she achieved perspective, laid back, and began to talk.

“I would like to live in a house with two other mature, intelligent women. One of them could be you.”

“As a friend or a lover?”

“We would see.”

She told me she had taken barbituates and that it was her habit in order to escape the turmoil of the world she met daily in the mental clinic and nightly in her scattered but intense affairs. I saw an ember burning out before me.

“I would like to comfort you. I think I can.”

“No! I don’t want you to, for that would form our relationship into a dependency trip. It’s hard to break a pattern that you start.”

I didn’t think she was right, for I thought of how I would need comfort in the future and she could repay me, then we’d be equal, but I didn’t say anything. I guess that was my problem. I didn’t say enough of what I thought. We drove back to the city. I was freezing from the cold Bay afternoon air that cut through my sweater. I suffered the cold that caught me two weeks later from that ride: Patience never called like she said she would.

I LEFT FOR MEXICO FEELING A BURST OF EXHILARATION with each succeeding motorcycle mile I put between myself and San Francisco. Although I had spoken about relaxing and a slow leisurely drive down the coast, I was moving as fast as my BMW could smooth me down the road. With the border crossing, I took a deep breath and began to inhale more and cruise with my eyes open to the new land. I didn’t think I was running from anything, but I was. I was running from my old butch self of sexual compulsion and chauvinism, of tough shirts and Levis. I was running from the woman who would compete with any man and come out on top; I was putting distance between myself as seducer and the real self I would find again in a quiet house in Guadalajara with the woman I first came out with four years ago, Tove. But first I was to meet two mirror selves, one in the form of a man and one a woman. After these encounters I would be able to see the shell of seduction I was leaving behind.

“Hey there gal, roll out of that bag.”

“Hey man, the world’s going already; open those eyes now.”

I pulled my tired lids apart a crack to see some hulk a few feet away bent in a supplicating manner toward my stretchedout form. I was in a trailer park in La Paz. I reached for my glasses.

“Do I know you?”

“No, but you should! You’re Barbara and you’re driving the BMW here. Isn’t that right?”

“Yeah, but how did you know?” What was this big black mirage? I wasn’t awake and the man was dancing a number on me.

“I was with that couple with the trailer from Pasadena, the doctor and that beaut of a wife with the cutest crotch you ever did see. You saw it now; don’t tell me you didn’t. They told me your trip and I thought, hey, here’s a chick I got to meet. I’m Bill.” My eyes were wide enough now to take in his towering muscular structure, his wide grin and engaging eyes. My nose began to smell the gin coming out through his pores from a session the night before. My ears began to hear the sexual exploits he was already laying on me; before I was out of one bag he was putting me in another.

“God, lady, I got to tell you about my friend Kathy who tripped with me. She was as gay as a catfish but we got it on one time like nothing else and had a ball catting around together. We’d make the cutest tricks together and both get our jollies off. Come on gall, roll out of that sack, we got some traveling to do.” This guy was something else. My little solitary trip was being invaded; like a cockroach coming into a sparkling tiled kitchen at night, this dude was trying to creep into my world.

We went for breakfast and we walked around town, and the conversation didn’t leave sex for one minute. I think I heard about every woman and man he’d ever made; I heard about every man his daughter had ever made, and I heard how he hospitalized his wife by throwing her down the stairs, and how he knocked up the dude he caught her with; I heard what a great lover he was, about every woman he’d had since the border crossing, how he could twirl his tongue, kiss every inch of a woman’s body dry from a bath, send her screaming up the wall shaking with lust for more of him. All this through huevos rancheros and a postcard home to ma saying “Great fun here, Love, Bill.” By the time he began to include me in his plans to form a seduction team appearing to others as a couple and was ready for a new round of evocative description of what we could do together, I was waving he and his marijuana headband a fast goodbye, encouraging him on his way to the Cape, where he was going to make a great masculine statement by turning back toward the States to pee.

I found a small hotel room for a few dollars, took a shower, made an uninspiring dinner on my camp stove, and decided to walk in town a bit before retiring. I was standing at a magazine rack in a coffee shop reading when a tan-faced woman with her hair pulled back leaned forward and looked inquisitively into my face, smiling.

“Aren’t you Barbara?”

“Do I know you?”

“You should. I’m Diane.” Diane from another life, Diane from four years past! Diane of Diane and Tove! Diane of the worms! We sat down at a small table and in recounting her past years of addiction from one drug to another I saw the familiar expressions, the way her lips crinkled up her cheek when she talked.

“I knew you were here before I recognized you,” she said, “I felt your Barbara presence.” This was the most incredible chance encounter. We were in Mexico one hundred miles from where Tove now lived, and they hadn’t seen each other since our days in the Petaluma house together. She got on the bike behind me the next day and we drove through vast maguey fields and lush jungles under baroque cloud-filled skies to Tove’s. Although Diane could stay but a day it was a grand reunion. I told her that were I to live that early meeting over with the two of them, I would never have moved in on their life the way I did, that I would have been more sensitive to her feelings. She told me not to be sorry for the past. After all, it was.

In the house next to Tove’s lived Consuelo who wore a greystreaked wig and had a layer of blue paint circling her manufactured eyelashes. Twirling and dancing, she pranced first around Tove, then me. Wearing the tightest pants and a low-cut yellow sweater, Consuelo, the lovely next-door neighbor, was caught in a sex role as constricting as my own. She knew of no other way of being but sexual, of physically coming on to men and women.

One night I could take it no more and decided to put her manipulative techniques to a test by allowing them to work on me. I wanted to be seduced. It was easy. We were lying in a room in her house watching TV, a Mexican, Kung Fu Western. Her husband was behind us on a mattress and her children were on either side of him falling asleep. Tove was intent on trying to understand the program from the corner she occupied. My arm against Consuelo whenever I could rest it there, my bare feet brushing hers, my body heat feeling hers, I was allowing myself small rushes of warmth. When her husband left for his night job we began wrestling on the mattress. Equally matched, we held each other off with our strong arms. She was a student of karate and I knew a little, too, so we matched eyes and yelled grunts until we dropped on the mattress sweating in the hot evening humidity. Tove left to go home and get some sleep while Consuelo and I waited for the late night news. I lay closely beside her. We translated the news back and forth and looked at her husband’s collection of Playboy. She obviously thought the nude pictures of women would turn me on. She took off her yellow sweater and her bra to show me her breasts, which she said she didn’t like because the brown circles were too big for her standard of beauty. I laughed at her, then again when she said her stomach was too pouchy from carrying babies. But I didn’t laugh when she tossed her head remembering the pain of childbirth and the nasty doctor who told her to shut up and forget that it hurt. And I wasn’t laughing either when I couldn’t suppress the desire of being close to this woman and began to wet kiss her arm. Then she giggled. I wiped the nervous lashing of her eyelids closed and tried to brush away the anxiety that made her brow quiver. I put my leg over hers on the bed. As enticing as she had been, she couldn’t come through and be in the least way tender to me. She pushed my face away with the palm of her hand. She kicked at me and laughed. She was as nervous as a housebound cat. She did try to rub me, to pet me, but her hand strokes were more from compulsion than feeling. I tried to explain that the act itself didn’t mean anything without feeling. That her strokes were nothing but flyswatter swipes. She turned to me in seriousness.

“Forgive me Barbara, but I cannot serve you with making love.”

“That’s quite all right, Consuelo. I understand.”

“You are not angry with me?”

“No, how could I be angry with you? You can only do what you feel, but I wanted to match your seduction with my own.”

“Seduction?”

“Yes, the way you flirt and entice.”

“But I act that way with everyone.”

“That’s the point.”

We hugged goodnight and promised to see each other the next day. I felt good that there was a probability the game-playing had moved to a more real level of encounter.

But I saw myself in Bill and in Consuelo. Duplicates of myself. How could I revert to that old and wearisome game of sexual seduction? It was a form of conquest. How could I be proud of capturing someone like a butterfly in a net? There was something else I wanted. Someone to like me for myself. Not for my ability to seduce, playact, or perform. Not for whatever talent I might have. Not for any display I might make, but for the simple and complex, the personality that I am. It was a simple desire; it seemed more clear than the masks of confusion I covered it with. I always wanted this simplicity but thwarted it through role-playing, through the diversionary tactics of seduction, through those power plays no one could genuinely respond to. No one could come through loving me. I was too well-concealed. For years I had blocked the possibility of getting what I wanted: to be liked and loved for myself.

I PHONED DUSTY, WHO I HAD BEEN SLEEPING WITH before leaving for Mexico. She had three other lovers at the time, but I was certain I was special. The international operator connected us. I heard a sleepy hello at the far end of a wire that miraculously allowed some form of communication.

“Will you accept the charges?”

“Yes.”

“But I can’t come to join you in Guadalajara right now; I am in the middle of another story for my book the press decided to publish and I can’t afford a disruption. Besides, it’s too expensive.”

“I’m glad they’ve decided to print your work, and I know your writing is most important to you.” My heart sunk to my toes and worked directly through the tile floor of the telephone booth into the Mexican soil below.

“How’s your love life?” I asked stiltedly. There was a long pause.

“It’s OK. I’d like to include you in it.”

“I thought I was included.” The roots were stretching out for strangleholds, finding rat tunnels with nothing in them. “Well, Dusty, best of luck. I’ll see you when I get back.” I wanted off the phone. For a while I didn’t want to see the light of day, but I knew I should reach out to somebody. The fountains of spray congealed through my visor; the long way to Lopez Mateos was shortened by my grief. At intersections a few long tears would choke out and find their way to my crawling heart. At last I arrived at the suburban home of my friend. Pulling my dark visor down over my face I hoped for a few more minutes of the hidden, almost savored grief, grief that told me, “Barbara, you are feeling,” but the warm, pale face of Tove met me at the door. In her arms I sobbed out the remnants of hurt that fell like leaves at our feet in a summer half spent.

“I think you’re a fine person when you are yourself Barbara, and I think others see it.”

“Then why am I alone when I want to be sharing my life?”

“A year ago I would have said you were doing things to prevent anyone from wanting to be close to you, but now I think you have a much better chance of finding someone to share your life with. Maybe you should look for a friend. I know how important a lover is to you but it seems that’s not working out now.”

A friend, I thought, how does one find a friend, go about making a friend? I know so well what a sex relationship requires, but a friend? I have no idea. Sex has been such a large part of my life for the last years, but I really could do without it now, for a while, I thought.

Tove was sensitive and tremendously aware of what was going on in her environment. I was there within her range of seeing, then I was the recipient of her understanding, which was profound. I brought her some coffee the next morning. We lay on the bed curled up against each other loosely, dozing. I was so comfortable with her. We could touch, stroke, kiss without eroticism. I could shit in front of her without embarrassment. I could do anything openly with this one who knew me so well. After the coffee an intense look crossed her face, a face a little older with lines that were not there the years before, a face as much older as my own.

“Are you still judgmental?” she asked.

“I try not to be, but maybe you should see for yourself.”

“You have a different attitude toward sexuality than I.”

Was she accusing me?

“Isn’t it true you can make love to someone you aren’t emotionally involved with? Someone you don’t even respect?”

“I think it is important to go with our sexual feelings. It is doubtful, although possible, I would be attracted to someone I didn’t care for or respect. If I did, I suppose we would have a purely sexual experience.”

“I don’t think I could ever do that, nor would I want to.”

There was more tension between us than the words told. Were we unable, as past lovers, to come together now as friends?

“What’s behind all this?” I asked, tears in my eyes. Couldn’t she see I was a sensitive individual, that I wasn’t into fucking around anymore, but at the same time I considered sex a basic drive and not one to be controlled?

“I didn’t mean to hurt you,” she said, her eyes liquefying. “I guess I was trying to see if you had really changed, if I could trust you.”

“But I thought you had been seeing the change all along. And here you are accusing me again of the past.”

“I was so hurt when we were breaking up and you were cold and didn’t want to talk with me; there’s no going back, but there’s so much past hurt that I have to be truly sure before I can be open again.”

“That’s surely fair, but please, no devious techniques. I think we can have different ideas and attitudes about various things, sex being one of them, without letting those come between us. What a relationship if each of us were to agree all the time with the other. Trust me. I care for you and I don’t want to hurt you.” She stood in the bedroom nude as a gooseberry.

“I’m sorry. I need to know you wouldn’t hurt me. I just have an awkward way of getting to the point.” We embraced and in that embracing promised each other to try again.

Nearly every afternoon I would try to assuage the build-up of sexual tensions that would arise from a self-imposed dose of celibacy in the Latin climate where the overhead sun slowly turned my skin to a golden bronze, where the next-door neighbor danced seductively in the evenings, where I woke in a foamrubber bed day after day having slept beside Tove all night without touching. I had erogenous dreams of water and houses and empty rooms where women made love to each other only to be frightened later by angry Mexican men. I ate meals of omelets of all varieties stuffed with potatoes and onions or vegetables and cheese, I drank exotic drinks of rich milk and papaya, and I was totally reliant upon myself for sex. So, after a sunbath and a light lunch, I might sit comfortably in the back room with my bare back upon the cold stucco wall, and while reading or finishing the last swallows of a soothing drink, begin the slow but continuous circulation of my finger that would result in an intense and gratifying series of spasms. I didn’t know any other way to take care of myself during these times, and this seemed adequate; in fact, I began to look forward to the red rug session in the white-walled room as if it were a date with myself. I could do something different each time. I could fanaticize a seductive Chicana rolling her tongue and eating me out, there could be a woman with a dildo with the expertise of practice, there could be Dusty with her long blue eyes watching my every change of expression as my thighs tightened and my breathing grew short, there could be anything and everything I wanted within those four walls where I took care of myself. Everything, that is, but the live, warm body of a lover. That time lay yet ahead, and nothing I could do right now would shorten it.

Years later, I was speeding up the Sacramento Valley in the warm evening air of a summer day singing my lungs out into my yellow bubble-helmet shell. Louder and louder composing verse after verse to insulate and protect from the trial that lay ahead, I sang:

I’m an independent woman if ya know what I mean

I drive a motorcycle in my old faded jeans

I go anywhere I want, do anything I please

I’m an independent woman if ya know what that means

TOVE. BACK TO TOVE AND SHE WAS WITH CONSUELO. I was vulnerable to my rampant jealousy but determined to conquer it. I was an independent woman, didn’t believe in monogamy, would be free of household ties and patterned restrictions. I could drive in, share and give, and drive out. Easy, I said, and sang and sang and sang climbing the red-black buttes toward paradise. Paradise, I thought, what an appellation; home of grave-kickers and bible thumpers; a place where neighbors wear binoculars, regulation marks for eyebrows and a straight-on sneer for us queers. Well, they wouldn’t get me. It was my own self I feared.

Brrrrrm, click, pull the bike back on its stand, and there five feet from me standing with legs apart and arms at side as if frozen by not knowing what to do was Tove. No hug, no embrace, just a “look who’s here” expression. I was prepared. This could be a social visit like it was in Mexico. I knew it would feel strange but I was prepared; I’d visited my ex-husband two years after our divorce. I could be friendly, I could see objectively.

And Consuelo? I could accept her. The table was begging a spread in the old dog pen next to the shack. I was a guest for dinner come unexpectedly but nevertheless warmly invited. Stuffed peppers and a watercress salad.

There Consuelo sat. Brown and solid with a little color washed out from being indoors. Not as robust as before, lean with the summer heat and her hair had grown six inches. I smiled. It was going to be easy. Back in the plastic lounge chair with boots dipping the sand, I made the tale of my travels entertaining and fun. Only my hands were nervous, and two fingers kept rubbing, an old Tove tick.

“You still love me or don’t you?” The impetus of her question tipped her forward. She was nearly out of the chair and in my lap, my nervous lap. I found her question very hard to answer as if she were shaking me out of myself.

“Yes.” I hesitated, but I couldn’t define why she had no right to that question. It was like someone asking me if I wanted to live when I had one breath left.

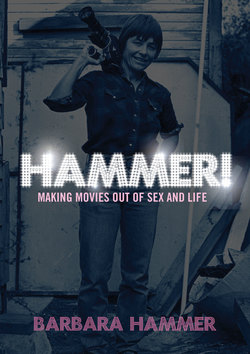

BH self-portrait, ink, 1970.

I began my art life writing poetry, painting, and drawing. I’ve always kept journals. Interesting to see my tools in this drawing: a motorcycle helmet, drawing pad, and ink pen. I hold a gun for protection so I can make my work. Once I figured out that I was a second-class citizen, I was angry.

BH in Ludwigsburg Castle, 1972.

Marie and I lived on an Army base in Ludwigsburg, Germany, where we taught school to the children of US Army personnel. As lesbians, we felt dispossessed. We acted out by hanging back on a tour of this famous baroque castle and taking provocative photos of one another.

BH on monument column, Germany, 1972.

There were plenty of wistful moments during our nine-month stay in Germany. Before long I was ready to go home. I had saved up enough money to buy a BMW motorcycle, have it flown in an Army transport plane to Philadelphia, and then drive it home to California.

BH writing, “My Life as Henry Miller,” Yuba River, California, 1970.

I lived alone for a month in an old, isolated cabin without electricity or running water. Right across the road was a path that led down to a river. I would not let myself explore or swim without writing one thousand words each day. The first thirty pages of the story are here and the rest is in my archive. I strongly believe an artist must be disciplined. You can’t write without practice; you can’t make films without commitment.

BH and Marie on BMW, 1973. Women’s Music Festival, Sunny Valley, Oregon. Once back in the States, we discovered a whole women’s world had blossomed while we were teaching overseas. Sitting and lying on my BMW we look pretty content.

PHOTO: RUTH MOUNTAINGROVE.

I Was/I Am (16 mm, 1973).

The films of Maya Deren (1917–61) opened a door for me as a young artist. I referenced her film Meshes of the Afternoon (1945) in my first 16 mm film. I transition from a princess with a white gown and tiara into a motorcycle dyke wearing leather. By now I had my own bike, a 750cc white BMW, which I bought in Germany, had flown to Philadelphia, and drove across the US with my first woman lover, Marie, who had her own 650cc black BMW.