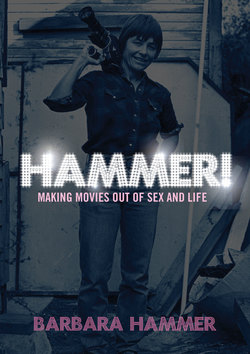

Читать книгу HAMMER! - Barbara Hammer - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

I think I’ve always wanted to live up to my name.

On my third birthday, I, Barbara Jean Hammer, received a leather basketball from my father, a prized object that for years I couldn’t even lift. Mother thought I was precocious and cute, and I loved to talk to strangers. So she arranged an audition for me with a Hollywood agent, dreaming that her daughter could be an actor like Shirley Temple. The agent said I would need professional training and elocution classes, which my family could not afford. And so the dream of Barbie Jean as a Hollywood star was born and died.

My parents met and graduated from the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana, married, and then moved west. I was born at the end of the Great Depression in 1939. My sister Marcia followed three years later. The California they hoped would afford them golden dreams left them instead with just enough cash for a small home in Inglewood, a working-class district of Los Angeles. My mother was a socially conscious housewife who, as president of the local Parent Teacher Association, organized the neighborhood to get sidewalks for our streets. On Saturdays I washed car windows for dimes at my father’s Mobile gas station, where a huge sign of a red horse with wings hung high. I loved that flying red horse.

I was most definitely a child of the Depression. We used ration cards for sugar and coffee during World War II, and mixed yellow dye into oleo to convince ourselves that we had butter. The sense of constraint and economy in our household deeply affected me; spending money has always been more difficult for me than saving, and I find great pleasure in making do with little.

I’ll never forget the day we heard shouting from the streets. We rushed out of our home. The war was over! White paper falling from tall dark buildings, scraps of brilliant rectangles dusting the streets, throngs of people filling the urban landscape—I must have seen these images in newsreels as it was too early for television, and Inglewood was more suburb than city. I still washed windows for my dad’s customers on Saturdays, but there was a different feeling in the air. The war was over and I could grow up.

I was seven years old and walking home from school with my younger sister when Jerry, a classmate, pulled my braids. Mom told me it was because he liked me, but I knew it was just the opposite. It was because I was Barbara HAMMER!

Even in my earliest storytelling I saw myself overcoming adverse situations. I wrote this fable the same year:

The Life of Red Flame

Red Flame was a colt. He belonged to a herd of horses. His mother, Chocolate, nursed him everyday. There was another colt the same size as him. His name was Wildfire. He and Red Flame played together. One day they strayed farther away from the herd than usual. They did not know where they were.

That night they saw eyes looking at them. The next morning Red Flame could not find Wildfire. He found a pool and by the pool were some bones. Red flame now knew what had happened the night before. He was thankful that he was still alive.

Red Flame saw a little cave. He found that he had to crawl to get inside of it. Finally he got through. On the other side of the cave he saw a little valley filled with grass and trees, it was like summer. By now Red Flame had grown to be a young horse. He became the leader of a herd and had many more adventures.

In fourth grade I couldn’t see the blackboard from my seat in the back of the classroom. I refused to tell the teacher and so I missed out on multiplication and long-division exercises. I didn’t want to wear glasses and went to great measures to avoid them. I knew what day of the week the eye doctor came to school, and I made sure I stayed home sick. Once I ran away, I was so afraid of my secret being discovered.

In fifth grade we had a substitute teacher who stayed for the year. We were studying the pioneers and were to make wagons out of soft pinewood. I couldn’t get my wheels round as much as I tried. I would file and file and invariably one of the edges would be flat. Mr. Substitute begged me not to give up, but I saw it was a losing battle and refused to file anymore. He was furious with me and pounded his fist on his desk.

My favorite teacher in sixth grade was Mrs. Bashor, who took her pet students to hunt snakes on Friday nights. We drove out to the desert in Joshua Tree National Park, and with bright headlights we slowly cruised on the black pavement that cut through the broad expanse of sand. Snakes came to the asphalt to warm their blood so they could move swiftly and catch prey. We learned to put our fingers behind their heads and lift them into the headlight beam so Mrs. Bashor could decide if we should take them back to the classroom. This made for great excitement, and I was rewarded for being the best snake catcher of sixth grade.

When I was in seventh grade we moved up in the world and into a new suburb named Westchester. There was a basketball hoop on the garage in our driveway. I could lift the leather basketball now and shot baskets on Saturdays. But by ninth grade, I was crawling out of my bedroom window to meet George in his souped up, lowered Ford coupe. We drove to a large, empty field nearby to make out. Then he would take me home, and I would climb back through the window until one night Mom and Dad were waiting. I was grounded for a month.

My grandmother was living with us again. Anna Kusz was born in a small village outside Ternepol in Ukraine and came to Ellis Island when she was in her teens. She could cook a scrumptious perogi, paska, and borscht. My babushka grandmother was occasionally a live-in cook for Hollywood celebrities. When I was six, she was cooking for D.W. Griffith. My mother, hoping something would come of it, made sure I was introduced to him and Lillian Gish. Nothing did.

When my grandmother was between jobs she moved in with us, much to my father’s chagrin. I’d see her at our kitchen table making art. Or crafts. I didn’t know the difference. Sometimes she was painting ceramics from molds of eighteenth-century women with bustles; the next month she stretched canvas and was painting with oils. Her largest canvas was a picture of her dream house: a small red-roofed cabin set near a lake and under a snow-capped mountain. In the foreground were eucalyptus trees. I loved this painting with the image of the woman, who I thought was Grandma, standing near the cabin door with her back to the viewer.

By observing her I learned that some people do just what they want to do for their entire lives. That appealed to me. I had tried different summer jobs as camp counselor, bank teller, salesclerk, and I didn’t like any of them. They were only a means of earning money. I wanted to be like Grandma.

For college I went to UCLA with an interest in student politics. As a sophomore—a babe without knowing it—I went on vacation with my sorority sisters to Catalina Island off the coast of Los Angeles. I sat down on the beach next to my friend Sue Canby and began reading a book when a young blonde man approached us to chat. I had no interest in him and continued reading as he talked with Sue. He said he wanted to go diving the next day. Then I became interested.

Clayton Henry Ward, born and raised in Oklahoma, took me diving for abalone. We brought in a huge cache, and cleaned and prepared them for my sorority sisters on the outdoor patio of Sue’s house. As we pounded the tough meat into flattened pancakes, we talked philosophy and looked at the stars. I was smitten.

Clay hitchhiked through South America during my junior year in college, sending me long descriptive letters of his adventures. He returned and proposed. I said, “Yes, but only if you take me around the world on a motorcycle.” We married, saved up for our trip, and two years later hitchhiked up through Canada to catch a freighter to England, where we continued hitching to Milan. Our 750cc Lambretta motor scooter was waiting for us. We drove through Italy, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Iraq, part of Iran, Afghanistan, and India, to Calcutta, where we caught a boat stopping in Vietnam and Hong Kong before we got to Japan, where we rested for a month before continuing on to Los Angeles. I learned how to go around the world for nearly twelve months on a thousand dollars; how to camp off the road where our tent could not be seen; how to buy in local markets the rice, vegetables, and meat I would cook with a backpacking stove every night; how to adventure, survive, and thrive. I was twenty-three years old and was traveling outside my own country for the first time. This was just the beginning—travel would become a lifelong passion.

Clayton and I drew architectural plans for a house that we built ourselves on six acres in Joy Woods, north of San Francisco. During the day I taught the children of hippies and discussed Gurdjieff in makeshift tents at the Wheeler Ranch, a nearby commune. At night, I sat by our wood-burning stove reading the biographies of artists such as Van Gogh and Gauguin.

I had married someone who provided me with an alternative to the middle-class values of my upbringing. But I wasn’t satisfied. Even with this remarkable young man, marriage was not for me. I wanted to be free. I learned from these biographies that being an artist meant living without the constraints of a regular job; and sometimes without the constraints of a regular relationship. The question was what kind of artist I would be.

I had written some poetry. I tried ceramics and sculpture. Nothing was right. Then I saw a poster reproducing something called “expanded painting.” The piece was very sensual and not too subtle: its painted Styrofoam rose up like a giant mushroom out of a base of wood shavings. The artist was William Morehouse. I decided to serve as an apprentice to him.

Bill announced in the first painting class that our model would be a woman on a motorcycle. That blew my mind. I stretched a canvas as large as life, and I put myself as close to her as possible. I was so excited to be standing right next to a woman on a motorcycle that I painted her with six arms and six legs. I had never heard of Duchamp.

Bill took me aside. We sat on the floor with our backs to the radiator as the other students worked at their easels. He told me how difficult it was to be a painter, that one had to make a thousand paintings before even arriving at a personal style. He told me that to be an artist was like living in a dark hole all alone. I shuddered at the thought of the isolation, but felt inspired by his confidence in me. The following week I commandeered an empty classroom one flight below the painting studio. I tacked a long roll of three-foot-wide butcher paper to one end of the room, and proceeded to unfurl it and tack it on all the walls around the room. Here was my dark hole. Here I would stay until I’d found my way, my stroke, my handwriting. Bill was a secondgeneration abstract expressionist, and I was filled with his talk of the artist’s unique individual gesture.

I saw myself at the heart of a drama. This allowed me to make my own story. I took acrylic paintbrushes loaded with color and swept around the room making marks. The forms were triangles, circles, and squares. I hadn’t heard of Cézanne but I was sure I had found my visual language, was proud of my independent move away from the class, and surprised at the imagery. Bill told me that both my movement around the room and the numerous arms and legs I had painted on the motorcycle woman showed more concern with motion than with paint on canvas. He brought an old 16 mm projector and some clear 16 mm film leader into class and suggested that I paint on it. I not only painted on the film, but I also projected this film onto the canvas. I painted with florescent colors and wired a black light to go on and off to make the colors move.

Then I got my first movie camera. It was a Super 8 mm motor-driven Bolex with a zoom lens. I was on my own motorcycle driving to Sonoma State to take a real class in filmmaking when I saw an old deserted shack with broken windows covered in red ivy. The site enchanted me. I parked my bike and went inside the creaky door. Looking through the cobwebs and dusty windows at the colorful ivy leaves outside thrilled me, and when I placed a bifocal lens an optomotrist had given me in front of the camera lens, adding movement, I knew what I wanted to do.

With the split lens I saw the image double. It perfectly fit my feelings of being a woman living in a man’s world. I ran outside on the sidewalk in the tiny town of Bodega filming my shadow until I saw a chair in the viewfinder. I slipped the bifocal in front of the camera lens and split the chair in two. I was filming the sidewalk again until I saw a man’s shoes in the frame. I climbed on a raised platform behind the man and shot him from above his head as he sat in the chair. I asked him to put a mirror between his feet, zoomed into the mirror filming his face, then I cut to my own. I was literally a woman living in a man’s world.

The projected work was larger than any painting I had made. I liked the fact that the audience could not walk as quickly by my film as they could a painting. Schizy (1968), my first film, won honorable mention in the Sonoma State Super 8 Film Festival. I was on my way! I left the confines of my marriage and moved to Berkeley.

In a few months I was running out of money and got a job teaching English at Santa Rosa Junior College. The sociology professor was teaching a class on women’s liberation and, when it didn’t interfere with my duties, I sat in. When the semester ended, a group of us from the class began the Santa Rosa Women’s Liberation Front. We met at my apartment across the street from the school. There, at the first meeting, Diane announced that she was gay. I immediately got interested. Not in Diane, but in her mysterious lover who would not come to meetings.

I had no anxieties about following my desire. Though I hadn’t consciously harbored lesbian feelings in the past, they emerged at this moment, and I was eager to act on them.

I met Marie, who became my first girlfriend. We traveled around Africa on motorcycles and taught in a German high school. After two years, we flew back to the States and drove from DC to California on our BMW bikes. I had a 750cc white 1972 with an Expedition-sized gas tank and she a 1971 650cc black one.

My mother never liked my girlfriend and she ignored her. My parents had divorced a few months after I had married. Mom told me they had agreed to stay together until I had matured, thinking that was best for me. I said it wasn’t, that I knew they were terribly unhappy and they should have separated long ago. My father had a drinking problem, and although I appreciated his humor and outgoing personality, I was deeply affected by his abuse of alcohol.

After their divorce, my mother was diagnosed with cancer. Despite our differences, I felt very close to her, and her illness had an enormous impact on me. I thought she would be distressed by my coming out, and I was sure she would disapprove. In an effort to protect her, I lied about being a lesbian. Of course, she knew anyway. To this day, I regret that I didn’t come out to her and deal with our feelings openly.

In January 1973, my mother died by her own hand or cancer (a question that will never be answered), ending for me terrible worry and concern for a woman I both loved and feared. I had spent three and a half days living in her Los Angeles apartment with my grandmother and sister during the coma from which she would never awaken.

Her body was cremated and I scattered her ashes over the Pacific Ocean. The consolation of her friends and the closing of her affairs busied my mind as I continued to live in her nearly vacated apartment. Finally, things were settling and I found an evening free to attend a woman’s gallery opening and to begin a new life for myself.

John, Barbara, Marian, and Marcia Hammer, Christmas, circa 1944.

We were the typical nuclear family. My mother wanted me to be a film star. She gave me all the lessons: tap, ballet, drama, elocution. We didn’t have money for professional acting school so I took neighborhood classes. During the Depression my father found a job managing a gas station and then he became a public accountant. He met my mom on a blind date at the University of Illinois, where they were both enrolled. My sister Marcia Lou was born three years after me so I was probably five when this photo was taken.

BH practicing ping pong, 1953.

What a look! I imagine it’s my father casting the photographer’s shadow. He liked to tease me. I won sixth place in the Los Angeles City ping pong play-offs that year.

Barbara, Marcia Lou, and Marian Hammer on the sidewalk of their new home in Westchester, a suburb in Los Angeles, circa 1952.

Plaid is the name of the game, but mackinaw is the key word in this photo. I loved these jackets and when one wore out, I’d get another. To me they signified the outdoors and Western riding wear. It must have been a cold January in LA for all three Hammer girls to be wearing this cloth. As for the hair, everyone has to have a poodle do once in her lifetime. More important, I am holding my first camera, a Brownie!

Date, BH, John, and Marian Hammer at AOPi Candlelight and Roses Dinner, 1960. I was an AOPi legacy. Little did I know of racism within the sorority, but when a young cheerleader who was half Hawaiian wasn’t pledged I left in protest for the UCLA dorms where I got a job as “dorm mother” for incoming freshman.

Jayne Mansfield and BH, 1959.

Sophomore year at UCLA, I was a cheerleader as well as president of SPURS, the sophomore honor society. I saw Jayne Mansfield in the bleachers at the football game and decided to present her with a blue and gold pom-pom. A photo op!

Sorority sisters on lawn of UCLA’s AOPi house, circa 1959.

As a teenager I was interested in politics. At Westchester High School I was student-body vice president. At UCLA I was elected to be the lower division women’s representative. Girls weren’t thought to be presidential material, so after serving one year on student council, I ran for VP. My name was helpful and my sorority sisters did their best to support my campaign, but I lost the election by ten votes.

Sue Canby and BH, Catalina Island, 1960.

Sue invited the sorority sisters over to her family home on the vacation island off the coast of Los Angeles. We are taking abalone meat out of the shell and getting ready to pound it for a big abalone steak dinner. Sue and I shared a love of “living off the land,” or, in this case, the sea.

Clayton Henry Ward and BH in Italy on our around-the-world motor-scooter trip, 1963.

The day after graduating from UCLA I married a young man from Oklahoma. I told him I would marry him if he went around the world with me.

175cc Lambretta and BH, circa 1963.

During the motor-scooter trip, I wore culottes. They came in handy because I could easily run when wearing them. They may have saved my life when I inadvertently approached a sacred mosque in Meshed, Iran, and was chased by a group of irate Muslims. I looked like a girl (and so I was chased), but I ran like a boy (and so I escaped).