Читать книгу Courageous Journey - Barbara Youree - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHREE

FLEEING TERROR

Late in the afternoon, he could see trees ahead, outlined against the gray sky. The people were walking now. Just a little longer. Keep going. We will stop among the trees. No planes had flown over for a while. At last, he fell exhausted among the others in tall bushes and acacia trees. He heard someone say, “Here we will be hidden from the enemy planes.”

Ayuel lay still several minutes. His heart raced as he gasped for breath and tried to push the images of the pumpkin patch with dead bodies from his mind. Rumors of water to drink spread among the crowd. The chunk of pumpkin had sustained him through the day, but now he needed to drink. He pulled himself up and followed the others to a pool of stagnant water. Like everyone, he knew it should be boiled but no one seemed to be thinking about protection of health. At this moment they thought only of saving their lives. Ayuel knelt, scooped the water with his hand and drank; then filled the filched calabash.

Everyone talked at once, asking the same questions: “Have you seen my mother?” “Have you seen Bol?” “Nhial?” “Do you know my brothers?” Ayuel recognized no one, but he pleaded, too. Where were his family and friends? Images of Tor and his little sister flashed across his mind.

He squatted down among strangers. Some didn’t seem to be from Duk or even of the Dinka tribe. Where had they come from? He rubbed his sore and swollen feet. He had carried his sandals, gripped in his hand the whole way. Mutkukalei. The Arabic word meant “died and gone” because the tire rubber was known to outlive the wearer. Ayuel shook his head as he thought about the jokes he and his cousin Chuei often made about the funny name. He squeezed his eyes shut and saw his sandals sitting alone in the desert sand, their owner dead and gone; then he slipped them on.

A few people had picked up food from destroyed villages. Others had escaped with a bundle of supplies. One man had grabbed a pot, full of dried lentils and maize. Ayuel moved closer to him. Groups began to form around the “kings” with food.

Ayuel offered to gather firewood but the owner of the pot said, “We cannot build a fire at this time. The enemy may still be close and would see the smoke rising above the trees. Rest, now.”

He lay back on the ground then quickly sat up, Acacia thorns stuck in his back. A stranger picked them out without saying a word. He moved to a better spot, carefully lay back down on dry grass and looked up through the trees at a hazy sky.

The shade felt cool after the day-long journey. Scavenger birds squawked overhead looking for corpses. I want my mother. And my father. He was going to take me to Bor, to the souk. Did they bomb Aleer’s cattle camp? What about Deng at school? His thoughts swam in images, repeated, merged and faded as he closed his eyes. Confused and terrified over what had happened and not knowing why, he mumbled routine bedtime words: “Our Father, which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name…” Sleep soon mercifully overcame him.

Ayuel awoke to the sound of low voices and the smell of lentils cooking. For a moment he thought himself at home. He had overslept and his mother was starting the day’s meal. Why hadn’t his half-brothers and sisters awakened him to take the family cows out? He opened his eyes and stared up through sparse branches. The blue sky and heat meant mid-morning. He had slept a very long time.

He sat up and turned toward the giggling of children. They were queuing up with open mouths to get a few squirts of milk from a solitary cow. Ayuel jumped up and ran toward the woman doing the milking. Just as he opened his lips to shout Mama, she turned into an older woman who looked nothing at all like his mother. With a heavy sigh, he rubbed his eyes and got in line behind the other children for his turn at warm milk.

As the day wore on, no one seemed to be in charge, but somehow they all silently agreed to remain in the grove of trees during the day for safety. It was cooler there. Occasionally they heard gunfire and helicopters off in the distance. Other villages were being attacked. Families separated—hurt, burned, killed. People milled about looking for loved ones or slept. Ayuel did the same. Never had he felt so totally alone. No familiar face anywhere. No one to tell him what to do. Everyone else must know at least one other person because they are all talking to each other. He shivered in the heat, not understanding what had happened or why. Too young to think about tomorrow.

After a very long day, a small group of people moved out into a clearing. Ayuel followed. They were listening to a man who stood on a large rock and spoke loudly in the Dinka language. “We must travel to the east—toward Ethiopia.”

Ethiopia? That’s a far-away country. No one can walk there.

The rest of the three or four hundred people came out of the grove of trees and huddled close to the speaker, keeping quiet. The man waited, then repeated they must go to Ethiopia, but he didn’t say why.

“Fill whatever containers you have with water,” the man said. “We will walk at night and sleep by day. Be strong, for the weak will perish and…”

Quiet vanished as people rushed to the pool of water. Ayuel rushed too, but bigger boys pushed him back, and by the time he filled his calabash, the water was muddied. His mother had always warned him not to drink dirty water, but others were. So he did too.

The journey began in the dark of night. As they walked, Ayuel noticed groups forming—age-mates together, women with daughters, a few men and older boys. Where were his age-mates? Age-mates stayed together their whole lives, and now he would have no one to grow up with. He trailed behind a group of nine-year-olds and looked for Aleer. They paid no attention to him, but he imagined them as his group anyhow.

On the third morning, the crowd found refuge next to a trickling stream of water, sheltered by trees. Ayuel drank all he could hold, for it made him feel less hungry. He sat under a tree on the bank of the stream and washed his face, arms and legs with the water remaining in his calabash. He’d been taught to stay clean. At dusk he would refill it for the night’s walk. As he tied the empty gourd around his waist with a vine, a boy from the group of nine-year-olds he had been following came and sat next to him. The boy clutched several strips of dried meat and handed Ayuel a few.

“What animal is it?”

“I don’t know. Somebody gave it to me. It’s food.” The boy grinned at Ayuel.

He took it, ripped a bite off with his teeth and chewed on the stringy, tough meat for a while. “Thanks,” he said.

After taking another bite, he looked up to find the boy had vanished. Slowly he got up to search out a place to sleep for the day. His legs ached and again he felt very alone and abandoned.

He walked along, looking down for a good spot without too many twigs until he became aware of someone coming straight toward him—a boy carrying a bundle of sticks. He glanced up and faced his cousin—same age, but more muscular, always the best soccer player. At last someone he knew. The boys ran and threw their arms around each other.

“Ayuelo!”

“Madau!”

Tears flowed. Sobs followed as all the anguish burst out. His cousin wore only a man’s cotton shirt with buttons missing, and Ayuel was still in the T-shirt he’d slept in back when life was normal. They sat on the dry grass, hugging, each comforting the other. Somehow it seemed strange to Ayuel that Madau was out here, just a little boy, wandering about all alone. He felt that he, himself, had already become a man, living on his own these few days. Yet seeing his cousin made him aware that he, too, was but a small child.

“Where’s your—your group?” the cousin asked when finally they sat apart, their sobs reduced to sniffles.

“Don’t have one,” Ayuel said simply. This was the first time he had cried since the bombing, and it left him exhausted. “I saw some boys I knew in a pumpkin field, but they ran away before I could talk to them.” He wiped his face on the sleeve of his T-shirt.

“I’m with several of our age-mates. You know them. Your cousin Chuei…”

“I’d love to see Chuei. He’s always saying something funny.” Ayuel watched the smile fade from Madau’s face.

“Not now. Chuei has trouble keeping up—and he cries a lot.”

“What about Tor?” He remembered the last time he’d seen him—wounded—and hadn’t stopped. Maybe he’d just imagined it.

“Someone said he died.”

“Oh.” Ayuel rubbed his eyes and took a deep breath. “Who else?”

“Your half-brother, ‘Funny Ears,’ and Malual Kuer. They just caught some little fish with a bucket and I went to get some firewood to cook them.” The dropped sticks lay scattered around them. “You know how to make fire by rubbing sticks?”

“Sure. Done it lots of times.”

“Come on.”

The boys gathered up the firewood and Ayuel followed Madau through the crowds, eager to see his friends.

At last, Ayuel felt less lonely. He now belonged to a group of five seven-year-olds—his age-mates—who stuck together as part of a larger group of older boys, a few girls and two women. They looked for food, ate, hid, slept and walked together. Malual Kuer’s father, who had been the pastor of the Christian church in Duk, had written songs based on Bible teachings. Sometimes they sang these as they went along.

Malual was his best friend. They’d never lacked for anything to talk about. Now, even more, as they walked side by side, they chatted constantly, which made the time go by. Before, he’d not played much with his half-brother, Gutthier. Their mothers resented each other since they were both married to his father. But now, their mothers were no more, so the boys became friends. Like the others, he teasingly called Gutthier “Funny Ears,” because his ears stuck out. Gutthier was tall like most Dinkas and considered the most handsome among the age-mates in spite of his ears.

Every day, a few more joined their group while others left, all Dinkas from the region of Duk. Some, like his age-mates, he knew very well. They had played together in the village. Others had common acquaintances or knew about Ayuel’s father, the chief and judge of Duk.

Each had a story to tell of the escape from his torched home—about those who died and the wounded left behind. Some said they’d found dead people whom they knew, laying on the ground. Thus, they believed all the people in that area must have been killed. A large group of boys had been found shot in one cattle camp, but Ayuel didn’t know which camp his brother Aleer had gone to. Ayuel had seen a few dead bodies, but no one he knew. He thought about what his family would look like dead and squeezed his eyes tight to shut out the images.

Most of the talk centered on who had survived and who had not. Like all Dinka children, Ayuel had been taught the names of his relatives, living and dead, and how they were related to each other—even those he’d never met. It all made sense now, all those names that had seemed so tiresome when he’d recited them for his father. Now he said them to ask if anyone had seen or heard of them. He learned about several aunts, uncles and cousins who had been found dead. Someone had seen one of his father’s half-brothers alive. Groups from his village began to travel near each other. Sometimes they mingled to ask about loved ones.

Three weeks passed. The hundreds became thousands walking across Sudan—a sea of people in columns moving east. No one seemed to know what happened to the man who had said to go to Ethiopia, but they still followed his orders to walk at night and sleep by day. Some boys carried bundles on their heads, unashamed to do as the women did. Food and water became scarce. There were always children crying, if not nearby, then in the distance.

At first when they passed through bombed villages, they’d found the dead, lying out on the ground. Now, as they crossed the desert, bodies lay under an arrangement of dried weeds and small branches—apparently an attempt at burial. And these corpses were the people who had gone ahead of them. Walking just like them. The awful stench of death was everywhere.

Arguments broke out continually, followed by shouting and fist fights. Mostly the Dinkas fought with the Nuers, who had always been enemies. Equatorians clashed with both of the other clans. Those who didn’t fight whined and complained. For Ayuel, weary from hunger, thirst and fatigue, a sense of hopelessness set in.

Many of the grown-ups began to say, “I can’t do it. I would rather die here.” Those words scared Ayuel for he knew that meant they were giving up. In Dinka culture, you must stay strong. You must take care of your body so you will have strength. But how can you take care of yourself with nothing? And with no one to tell you what to do?

One evening, as they prepared for the night’s walk, Ayuel and his age-mates watched in disbelief as the women formed new groups and started walking back the way they had come, toward the setting sun, not toward Ethiopia. Back to the burned villages? There had never been many men along, but most of those remaining left with the women. Ayuel had heard stories that the men were first to be shot in the attacks. They may have killed my father at his office in town, he thought. He tried not to think about how that would happen.

As they stood watching the adults leave, Malual Kuer turned to Ayuel and recited a common proverb they all knew: “To quit is a shame on future generations.” Others around them nodded agreement or repeated it in low voices.

Ayuel remembered what the religious leaders had said in teaching from the Holy Bible: “God punishes the children and their children for the sin of the fathers to the third and fourth generation.” Surely it is wrong for the grown-ups to leave us children to find our own way. We will be punished for their wrong, he thought, but said nothing.

Most of the girls, in keeping with tradition, chose to go with their mothers or with women they knew. A few of the boys hung onto their sisters or mothers and quietly pleaded with them not to give up. Not to leave them to walk alone.

The abandoned children stood in silence as the setting sun dropped out of sight, leaving streaks of red across the western sky. The outlines of their grown-ups diminished and disappeared into the dusk. With the rest of the boys Ayuel turned and walked into the gathering darkness.

The two women and all but one girl had left Ayuel’s group. Other boys joined. The reshaped group numbered seventeen, all of them Dinkas from the Duk region. To keep peace, they avoided children from other tribes and regions. One of the older boys had a cooking pot, which would be put to good use from time to time.

Ayuel and his four age-mates—Gutthier, Madau, Malual Kuer and Chuei, who had grown up together—stayed. Everyone accepted Donayok—another cousin of Ayuel and the oldest at fourteen—as their leader, though they all looked after one another. Six boys were between eleven and thirteen, the others younger. And the only girl, Akon, was ten, a cousin of both Gutthier and Ayuel. Though she was as tough and strong as the boys, they all kept a protective eye on their “sister.”

Almost daily now, Ayuel found cousins and other relatives among the different groups or heard news of the dead ones, but no word of his parents or blood brothers and sisters.

In the evenings, just before the walk began, Ayuel could hear the Animists practicing their religion, dancing and chanting prayers to the spirits. His people had left the traditional beliefs two generations ago, when his grandfather converted to Christianity, but he hoped the spirits of trees, rocks and sky would help them all.

One night seemed especially tedious. Ayuel tried to pray to God as he had been taught by his mother and also in their Episcopal church, but his mind could not form the words. His stomach felt hard as he put his hand to it—swollen from lack of food. Don’t ever give up. His brother Deng’s words throbbed in his head—his advice from their last day together. How could he keep going? What good was it?

There was little talk among the group of seventeen now. Every bit of energy must be saved to move one foot after the other and not fall. Some in other groups had dropped and not gotten up. Death happened daily, but so far none of the seventeen had gone down. Chuei was keeping up or sometimes Donayok would carry him on his back. Chuei, the jokester, never said anything funny anymore.

Cold came with night. Poisonous scorpions and cobras hid in the darkness, ready to strike and kill. Ayuel could hear them, or thought he did. Terrified of dying, he tried to keep alert at all times. The evening before he had seen a girl not too far away screaming from a snake bite. He hoped someone helped her, but knew she probably died. He had walked on and hugged his skinny shoulders with chilled, bony fingers in an effort to bring warmth.

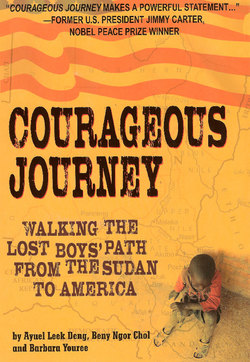

Map of Sudan, courtesy of the CIA World Factbook