Читать книгу Courageous Journey - Barbara Youree - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSEVEN

GRIEF AND WELCOMES

A few days later, Ayuel and his best friend, Malual Kuer, went down by the Panyido River for firewood to cook the day’s meal. After bathing and collecting a nice bundle of sticks, they sat on the bank to rest. The water’s edge swarmed with masses of people in and out of the river but the two boys kept to themselves. Certainly they would boil the drinking water they had brought back.

While they leaned against tree trunks, Malual began singing a Dinka song his father had written during the famine a few years back:

Lord, we know that we have wronged you many times.

We know that we just believe in words, but not in spirit.

So, Lord of the whole world, if You weren’t there,

We would have no seed left during this famine.

So, Lord, come and bless us,

Give us rain so that our cattle can feed on grass.

Give us food to eat so that our souls can live.

Ooh, Lord help us!

When Malual stopped singing, he said, “God is punishing us.”

“Why? Why do you say that?” Ayuel said. He looked at his friend and could tell his words were serious. He seemed to have a strange glow on his face.

“Look at us. We are so young, just children. We don’t have mothers and fathers, sisters or brothers. We don’t have spears to hunt animals. Today we cook the last little bit of food we have. So what kind of people are we? Why is God punishing us?”

“I cannot answer that.” Ayuel threw a pebble into the river and watched the circles grow wide where it sank. He tried to find some reasons for Malual. “Maybe because our fathers or grandfathers were not good. They did something bad. Perhaps God is punishing us because our fathers did something against the Lord. That could be why He’s punishing the children of Sudan.”

“You know the scripture,” Malual said. “It says God is a jealous god. He carries revenge on the children for the sins of the fathers to the third and fourth generations.”

The boys picked up the sticks for firewood and headed back to the camp. On the way, Malual complained of stomach pains. Then he told Ayuel he was having bloody diarrhea.

“My mother used to boil roots to make a tea that helped that,” Ayuel said. So they dug roots with their hands and took them back and made tea.

“We have no knowledge of these roots, whether they can be used for medicine or not,” Malual said. “They might be poison.” He wouldn’t drink the liquid, but lay down and held his stomach.

Malual Kuer, the strongest in the group, became weaker and sicker by the hour. Ayuel sat beside him, giving him water and trying to get him to eat. They talked no more of God’s punishment.

On the morning of the second day, Ayuel held Malual’s head in his lap and fanned away the flies. We’re age-mates. We’re supposed to grow up together. Please, Malual, don’t leave me. Please, God, don’t let him. Tears dripped off his chin and fell on his friend’s neck. He wiped them off with the tail of his T-shirt. As he looked into Malual’s face, he saw that strange glow again.

“I’ll ask God about it,” Malual whispered. He closed his eyes and was gone.

Lord, we know that we have wronged you…Lord, come and bless us. Malual’s voice rang in Ayuel’s head. He remembered first meeting Malual when he’d followed that angelic voice through the village. Since that day, they had remained close friends. Sometimes Ayuel sang the words aloud as a way of mourning for his friend—his age-mate, his soul-mate. Yet the song was always there from the moment he rose to the moment until he lay down at night. So give us food to eat so that our souls can live. Sometimes just a line repeated itself over and over. Other times, he would sing the whole song as a prayer.

One morning after the worst of the cholera had subsided, the fourteen sat around drinking what they loosely called tea—water left from boiled leaves. Gutthier turned to his friends and said, “So… this is worse than when we walked every night. We could keep walking then because we thought we were going to a good place. But now we are here, and it’s not a good place.”

“I heard yesterday that there are other camps in Ethiopia,” Donayok said, sipping his tea from a gourd shell. “Dimma and Itang. Close by there is Markas. Maybe we came to the wrong one.”

“I hear they teach you to shoot guns in Markas and the food is better,” Madau said.

Ayuel remembered that Malual had once said he would like to be a soldier.

“I think Markas is not far from here,” Madau said, “I’d rather walk than sit around this smelly place all day. Who wants to go?”

Before they could make a decision, a commotion broke out around a vehicle that apparently had just pulled into camp. Since the meager food supply had arrived yesterday, this must be something else. A man’s voice boomed over the microphone. What was he saying? “Listen, listen,” Donayok said, motioning for them to hush.

The officer was standing on what they later learned was a jeep. “Tomorrow is a very important day in our lives. A congressman from the United States of America is coming here to visit you. The whole world will then know what terrible things are happening to the children of Sudan and in the refugee camps here in Ethiopia. They will want to help us. It is not right for you to endure this tragedy.”

Several people started shouting, “No, no! It’s not right!”

“What is a congressman?” Ayuel asked. “And where did he say he was from?”

“Unite something,” Madau said. “There are some Nuer boys here from Unity. That’s the town with an oil company where the government killed everybody in a raid. I hope that’s not where he’s from.”

“We will want to welcome the congressman,” said the official. “So I am going to teach you some English words. This is what the words look like.” Two men held up a huge banner attached to long poles at each end.

Ayuel had seen Arabic words before, but this didn’t look anything like that. A wave of excitement came over him. He was going to learn something.

“This is the first word right here.” The officer pointed to some marks at the left on the banner.

“I can read that,” said a boy, whom Ayuel had never seen before. He read off the words rapidly and then repeated them in Dinka. He grinned at his own accomplishment.

Amazed, Ayuel said, “How do you know how to read English?”

“Just do.” He rattled off a bunch of unintelligible words.

Ayuel was duly impressed, but said, “Let’s listen to the officer.”

“This says welcome.” The officer moved his stick to the next group of marks. “Does this look like the first word?”

A chorus of voices shouted, “Yes.”

“Right. Now repeat after me: Wel-come, wel-come.”

“Wel-come, wel-come.”

After teaching them to say American congressman, the man said, “Now some time tomorrow the congressman from the United States of America will be here. When the men hold up this banner, we will all shout out the English words you have learned. Now go practice saying these words to each other: Welcome, welcome, American Congressman.”

The boy who seemed to know English turned to Ayuel and offered his hand, “My name’s Emmanuel Jal.”

Ayuel shook his hand and introduced himself. “Am I saying it right?” He repeated the words they had just learned.

“Almost. It’s like this.” The boy practiced with him a few times until a bunch of his friends came by. “See you later, Ayuel.”

The next day, Ayuel—as well as the whole camp—watched with curiosity as long metal poles with some boxes atop rose at the place where the trucks usually stopped. Late in the afternoon some extremely bright lights shone from the boxes. Like the sun, they were too bright to look at directly. Donayok put Ayuel up on his shoulders so he could tell the others what was going on.

“They’re setting up a shade for the congressman, sort of a shelter with four wooden poles and a roof. Now a whole line of vehicles is coming toward the lights,” he reported. “But only one is a truck. The others are low with tops on them. I see people inside.”

“They’re called cars,” Donayok said with a laugh. “I’ve seen them in Bor.”

“Well, there is one that is very, very long with lots of windows. It has little flags on each side and it’s black and shiny. They’ve stopped by the lights and the shelter now. Two men are getting out of the long one—the long car. They look very strange, wearing funny clothes with sleeves that come down to their hands. Their skin is pale, much lighter than any Arab.”

“They’re khawaja, white people,” someone said.

“Now what are they doing?” asked Madau and pulled eagerly on Ayuel’s foot that hung over Donayok’s shoulder.

“Someone is pointing something big—I don’t think it’s a gun—right at the two pale men, the khawaja.”

“That’s a TV camera,” an older boy from another group said. “They can make pictures that move with it.”

How can pictures move? That’s not possible.

“Some of our men are setting up a tall desk, like a church pulpit, under the shade.”

“Here comes the banner!” shouted Madau.

From his high perch on Donayok’s shoulders, Ayuel scanned the crowd for Emmanuel Jal, but never saw him.

As two men held up the banner, a man from the Ethiopian government jumped into the back of the truck with a microphone. Pointing to the banner, he began the chant: “Wel-come, wel-come!”

“Welcome, welcome! American Congressman,” yelled the crowd over and over, not so much to welcome the congressman, but to show off their new knowledge.

“Very good,” said the man at the microphone. “Okay, okay. That’s enough. We do heartily welcome the congressman who has come all the way from the United States of America to talk to you.” He handed the microphone to one of the white men and clapped enthusiastically along with the crowd. The government man said the name of the congressman but it sounded so strange that Ayuel and his friends couldn’t remember it.

“Let’s move over where we can see better,” suggested Gutthier. Ayuel slid down from Donayok’s shoulders, and they found a spot in the middle of the assembly. The crowd grew silent and sat down to hear what the man would say.

The congressman got out of the long car and stood under the shade behind the pulpit. He spoke a few words over the microphone in a strange language that Ayuel guessed was English like “welcome.” Then the Ethiopian man repeated them in Dinka, for that was what most in the camp spoke.

“Thank you for your very kind welcome,” the congressman said. “I am happy to be with you this evening. The government of the United States of America has heard of the terrible situation here, and I have come to see for myself. It is, indeed, worse than I ever imagined.” He took out a white cloth and wiped his face.

“I have let the United Nations know about you. Shortly they will send you food, clothing, soap, tents and blankets for cold nights.” The assembly of thousands roared with applause. “Then we will set up medical clinics and burial grounds. You will have schools and teachers.” More applause.

The congressman talked on for a very long time. Much of what he said Ayuel and his friends didn’t understand, but they understood what meant the most. Their lives were going to be better. The whole world would help them.

One week later, a convoy of trucks brought food and clothing. They brought shovels and machines to bury the dead. Ayuel made a rag ball from his torn and ragged T-shirt. It would be good for playing pitch. His new one had been worn by someone before and had words on it, but it smelled clean and felt soft against his dry skin. His new shorts wouldn’t stay up over his thin body so he tied a vine through the loops, but he kept his old mutkukalei on his feet. They had served him well.

Life became better. Aid workers from various countries came to help the sick. Men with razors came to shave off the children’s orange and brittle, lice-filled hair. More bags of clothing arrived, marked “U.S.A.”. Each group received a chunk of soap for bathing and washing out their cooking pots, containers for storing grain and a bucket for carrying water. Now, in addition to maize, the food rations included beans, oil, sorghum and wheat flour. In the wooded area near the river, the boys often found mangoes and other wild fruits.

A few days later the people were ordered to form several lines, each in front of an official of some kind. After standing long hours in the hot sun, Ayuel arrived in front of a man who squatted down to question him.

“What is your full name?” he asked. “And you are from which clan?”

“Ayuel Leek. Dinka, sir.”

“How old are you?”

“I think, sir, I am still seven.”

“Do you have a mother or father, sister or brother in Camp Panyido?”

“No, sir.”

“To your knowledge, do you know if anyone else in your immediate family is living?”

“I don’t know, sir. I hope so.”

“Name any half-brothers and sisters, cousins and any relatives that are here in camp.”

Ayuel mentioned every relative he’d met on the journey, including his uncle, the SPLA officer, even though he’d never found him in the camp. Of course, he mentioned Gutthier and Madau.

“Ever been to school?”

“No, sir.”

“Next.”

The fourteen had become separated from one another when the assembly rushed to get in the lines. Now, near the end of the day, they gathered at their new home at the foot of a dead acacia tree. One of the boys had found a woman’s shawl, which they stretched out from the tree branches and attached the ends to two poles. This made a shade for a few children at a time.

Since Gutthier and Madau had been first to finish the questioning, they brought water from the river for everyone. When Ayuel arrived, he fell exhausted under the shelter. After a while, he sat up and slowly drank the boiled and cooled water from Gutthier’s plastic bottle. “We don’t have any more food, do we?”

“No,” Madau said. “We finished our supplies last evening. Let’s go gather some tree leaves. This old acacia tree probably died because people ate all the leaves.”

“I’m too tired from standing so long,” Ayuel said. He lay down and closed his eyes, but could hear the rest of his group gather and talk about the day’s experience. He recognized each voice and automatically counted off the names as he had done so many times in an effort to keep track of everyone. He drifted off to sleep and when he opened his eyes, it was nearly dark.

“We’re all here except Akon,” Donayok said with strain in his voice. “Did anyone see her today?”

Ayuel sat up, wide awake. “I haven’t seen her since we boiled the tea this morning. Maybe we should go search for her.”

“No. She knows where to come,” Madau said. “I saw her in another line, talking to some other girls. They’re her cousins on her father’s side. Her mother and mine are sisters, so we are cousins, but on our mothers’ side.” The explanation was not unusual for a Dinka child who learned to recite the relationships of his relatives at a very young age.

Just then, Akon appeared with two taller girls, one on each side. The boys all stood up, “We were worried…” Donayok said.

“Here, I brought you some bread,” she said and handed out some dried scraps, obviously from the dump. She smiled broadly, showing real happiness. Ayuel thought she had invited the girls, whom he recognized as Akon’s cousins, to join their group. That would be great; they needed some mother types.

“These are my cousins,” Akon announced and then choked up, unable to speak.

One of the girls said, “We found Akon this morning in the lines. Our mother is still with us. And our little brother, about your age.” She pointed to Ayuel.

“Our father was shot. Right in front of us,” the other girl said without showing emotion. “Akon is going to live with us.”

The boys remained standing in stunned silence. No one had just left since forming the group of seventeen. Akon had always been a comfort to Ayuel. “I’m happy you have a family,” he finally said. “But we can still see you every day.”

“Where is your family’s base?” asked Madau. “I’m glad you will have a mother.”

“Didn’t you hear?” Akon said as she wiped tears with the tail of the new T-shirt that she wore over a flowered skirt. “They are putting all the families on the far side of the field. I have to go now. It’s getting dark.”

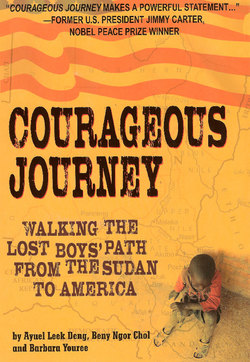

Map of Ethiopia, courtesy of the CIA World Factbook