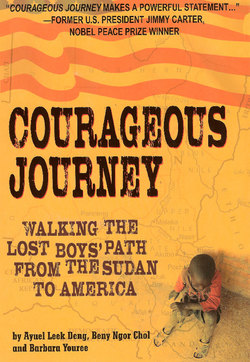

Читать книгу Courageous Journey - Barbara Youree - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE

GRIEF AND JOY

“ Something’s wrong over there,” Ayuel said as he and Beny Ngor Chol Swalked down the dirt path toward the bulletin board in the refugee camp. “Wonder why all those people are headed to the riverbank.”

“Maybe someone’s going to make a speech,” suggested Beny, yet unaware of the anxiety Ayuel was feeling about the gathering crowd. “It’s probably too early for ‘The List’ to go up anyway. Come, let’s see what’s going on.”

The two young men turned from the International Rescue Committee office where they were headed and quickened their steps toward the dry riverbed. Miles of mud and straw huts dotted the vast plateau near the equator, home to orphaned children and a fewer number of intact families—80,000 in all. In this desolate place in Kenya, Africa, only a few scrub trees survived—much like the fading hopes of the forgotten inhabitants.

Ayuel and Beny joined several people running toward the happening at the riverbank. The sound of pounding feet—unaccompanied by voices—lent an eerie foreboding to the stillness. A breeze swirled dust in the warm morning air. The screech of a single hawk drew Ayuel’s eyes upward as he watched the raptor swoop low, flap its wings and soar again. Then, something else silhouetted against the emerging rays of sunlight. The excitement he’d felt about searching for his name on The List melted into horror. Beny saw it at the same time, and both young men stopped and stared.

There, suspended from a high limb of the tallest tree on the bank, hung a body, limp like a dead bird.

A flash of light, then another, recorded what had happened. Why do they have to do that? As the cameraman stepped back, two other workers from the International Rescue Committee came forward with a stepladder.

“Who is it—this time?” Ayuel whispered to another friend of his, who stood at the edge of the crowd. Ayuel, a sensitive young man with fine features, felt his mouth dry and his breath come in short jerks.

“Majok Bol. He’s from Zone Two Minor.”

And from the Bor region where I’m from. And Dinka too, like me. He remembered the tall, quiet boy with the charming smile.

As the two officers cut the rope and gently lowered the body, murmurs rose from the group of onlookers.

“Majok was our best soccer player…”

“Always a good sport.”

“He was the smartest in our group,” a boy said through quiet sobs.

But no one asked why. They knew. All of them had thought about it at one time or another. Suicides didn’t happen often, but when they did, those who had passed their childhood here in the refugee camp were left traumatized.

As the men carried the body away, the crowd dispersed—some crying softly, others hissing angry words between their teeth, or just gazing blankly into their own hopeless futures.

Ayuel and Beny stood facing each other—shocked and devastated—not knowing what to say. Ayuel looked down at the spiral notebook he still carried in his hand. It contained the math notes he’d gotten up early that morning to study. Why didn’t I know? His after-school social work included suicide counseling to those showing signs. No one had alerted him.

Now, he recalled the day that first posting had gone up. He saw Majok leaving just as he’d come to check for his own name. Majok had muttered something about it being hopeless to expect to see his name. Ayuel had tried to encourage him by saying there would be more listings and he was well-qualified. Why didn’t I take his comment more seriously?

The sound of a stapler pounding the wooden bulletin board by the IRC office interrupted their sadness. Ayuel knew the posting meant ninety more names of lucky ones on The List. Since applying two years ago for refugee status in the United States of America, he had lived with the tension of hope. He knew some of the previously chosen ones who had already flown away to the western world, a fantasy place he could only read about—where ordinary people lived in enormous painted houses, drove big shiny cars, got fat from abundant food, and education was free for everyone.

The woman he loved and hoped to marry someday had left on the very first flight. She had gone to the United States. If ever he were chosen, he might be sent to Australia, the Netherlands, Canada or—if he were really lucky—the United States. Since that was a very big country, would he even be able to find her?

“You’re going to see if your name’s on it, aren’t you?” Beny asked. Thoughtful and introspective, the event visibly distressed him, but he was also practical.

“Not yet,” Ayuel responded. “Let’s find out what they’re talking about.” IRC workers and several young men huddled together under the tree. A few wide-eyed younger children looked on.

As Beny and Ayuel approached, they recognized one young man who sobbed uncontrollably, standing just outside the huddle. The man had shared sleeping quarters with Majok. Ayuel put his hand on the man’s shoulder. “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.”

“I heard Majok get up—about midnight—and leave our tukul. I just went back to sleep.” The man wiped his eyes with his shirttail. “This morning I found the note—the note they are reading.”

The huddle broke up and one of the IRC workers handed a piece of paper to Majok’s roommate. “We’ll need this back to make the report,” the worker said. “We’re sorry for your grief.”

The roommate offered the note to Ayuel and Beny who silently read it together:

I don’t know why my life seems so unpromising. Over all the years, today and tomorrow look the same. I lost my mother and father, my only sister, my brothers and recently my beloved younger brother. What kind of life is this? I am tired of this life and I am unable to continue this pain anymore.

Ayuel’s emotions tore him in opposite directions. How dare I hope to find my name on The List when I’ve just witnessed another’s hope so miserably crushed? Yet, he yearned to be chosen. Ayuel and Beny walked in silence toward the posted names. Both had risen to positions of leadership but Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya offered nothing more—no future to anticipate.

Ayuel had spent the past ten of his twenty years here, and four years before that in an Ethiopian camp, doing his best, never giving up. But to what end? If he returned to Sudan, his only means of survival would be to join the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army and fight in his country’s civil war. The cause was just. Colonel John Garang led his forces against the Arab-Islamic government that had declared jihad against the Black Christian and Animist South. The radical Muslims intended to enforce their harsh sharia laws, deny religious freedom and obliterate the villages over the newly discovered oil fields. But Ayuel, sick of the killing, had no desire to shoulder a gun.

Finding a job in Kenya was impossible—foreigners were not allowed to work here. According to rumor, only 3,800 out of the tens of thousands of refugees would ever find their names on The List of those chosen to go to the United States. Yet his heart pounded in anticipation.

Ayuel stood behind the knot of anxious youth and watched those at the board move out of the way. This was a silent ritual. Those who had searched long and hard for their names without success crept away with sagging shoulders and stony faces. Ayuel had done that many times. The few who found their names suppressed a smile, but the exuberance in their eyes belied their modesty. Ayuel inched closer, a step ahead of Beny. More hopefuls crowded behind them. He stretched his tall, slender frame, but the morning sun, bouncing off the white sheets of posted papers, made the names impossible to read from where he stood.

Ayuel took a deep breath and moved to the front. His eyes darted to the page headed “1992.” That was the year he’d arrived at the camp as a starving, emaciated waif.

Ayuel Leek Deng.

There it was in black letters! His name. With a double blink, he looked again, bit his lip and slipped out of the way. He picked up his letter in the UNCHR office. It would give the details of where and when he would be going. Heading toward the straw and mud hut that he shared with three other young men, he dared not glance back to see Beny’s fate. His friend would catch up with him.

Light has come to my darkness. Just as he allowed himself a broad grin, a hand slapped his back.

“Hey, I made it too.”

After shaking hands and sharing a hug with his friend, Ayuel said, “Beny, you did? I’m so happy for you. When do you leave?”

“This Sunday,” Beny said, waving his letter toward the blue sky. “I’m going to soar up there in an airplane and fly away from here to the utopia that is the United States of America.” Coming back to Ayuel, he added, “I saw your name before I saw mine. I hope you leave the same time I do.”

Ayuel unfolded his letter. He’d hardly looked at the details. “No, I don’t leave until next month, August 5, but I go to the same orientation as you. That’s good.”

“Can you believe it? That starts at eight tomorrow morning.”

Ayuel was laughing now. With no one close by he could show his joy. “I’ll miss my math exam, but nothing else matters now.” Ayuel clenched his notebook. The friends slapped each other’s hands and rejoiced like children with extra food. Although he was only three months away from earning his high school diploma, Ayuel had been told that the paper from a refugee school would mean little in the United States. “Only what you have kept in your head will count,” his teacher had said.

Having received special training, Ayuel counseled those with emotional or spiritual problems and helped new arrivals to the camp deal with their anger by expressing their emotions through drama. Beny, two years older than his friend, had finished his schooling the semester before and now worked on staff as manager of the Community-Based Rehabilitation Program, helping the handicapped.

“Wonder what it will be like to look down from the airplane,” Ayuel said. “From here, it always seems so tiny that it’s hard to imagine people inside.” His stomach grew tight and queasy just thinking about it.

“Guess we’ll soon know.”

That evening, after the one daily meal of a wheat flour and maize mush, Ayuel walked to a different area of the dry riverbed—far from the morning’s tragedy. He needed time alone to deal with conflicting emotions that ranged from deep sorrow over Majok to exuberance about his new opportunity. No one else he knew in his zone had made the weekly list. He saw the pain in the eyes of those who congratulated him.

As he sat on the riverbank, he realized the future was too hazy and unreal to imagine. The past that he knew all too well flooded over him. He thought of the spilled blood of over two million of his fellow Sudanese people who still cried out for liberation of their country. The dead included his parents, his baby sisters and the countless children who had not survived the long walk to Ethiopia or here to Kenya. And then there are those who drowned crossing the Gilo River.

His two older brothers, Aleer and Deng, perhaps were among the lost. Aleer had made it to Kenya, but left to go to the university in Uganda. Ayuel had not heard from him in four years. He hadn’t seen Deng since the bombing of their village in 1987. Could they have survived like him? Not knowing brought constant worry. And now there was Majok Bol, who had died from lack of hope.

I must honor all of them. I must find a new life, a better one in the United States of America. I must make a way for those left behind—still suffering and dying from the government’s terrorism against its own people. I am a seed of the new Sudan.