Читать книгу More Than Everything - Beatrix Ost - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Farewell

ОглавлениеI WAS THIRTEEN YEARS OLD. My parents still lived on our estate in the country. I lived in the Max-Josef-Stift Boarding School in Munich. They had picked me up there. My mother was chauffeuring us in our Blue Wonder through the city of Munich and further out through the suburbs to the airport.

I sat in the back seat; next to me was Lexi, Father’s dog. I felt happy to sneak out of the dorm for a few hours, and also happy to see my sister, Anita, again.

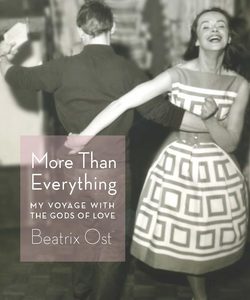

I had put on my favorite summer dress, blue background, strewn with blossoms. I wanted Anita to admire me in it, even though it was still cold, perhaps March. But that was precisely why she would notice the dress. Even at this time I still felt like her accomplice, for I had been carrying around her secret like the treasure it had not been for several years.

It was 1953, the airport under hasty reconstruction. Lonely perspectives, colorless de Chirico. Unadorned building sites surrounded a broad plaza. Further off, miniature people shoved lorries about, cranes combed the gloomy sky. We wound our way in between chain link fences, warning signs, and war rubble, and parked our car in regulation fashion, where the arrows indicated. Fritz took Adi’s arm and propped himself up heavily on his walking stick. His feet laboriously tapped their way up the gray stairs to the entrance portal. Up above, a rusty tin sign said “Riem Airport.” Through the departure lounge strode American soldiers; way up on a balcony, several people observing the plane traffic were silhouetted in the glass windows.

We walked past the rows of waiting-room benches, the flower stall, the newspaper-and-souvenir shop, and pressed on toward a rotating glass door. My father stood still and pondered it: glass panes dissected him into pieces that did not fit back together quite properly. He hesitated. But then my mother pushed one of the panels aside and hustled Fritz on through.

Before us stretched a large dining room. At some tables people were chowing down; all turned to stare at us. My parents went slowly, accompanied by shrill restaurant chatter, past chairs and tables, toward the little group. Lined up against the wall opposite, a tableau vivant: my sister, Anita; her children, Franzi and Christine; and her husband, Heinz, next to a tired lime tree in a red pot. I had taken Lexi, who was reluctant to go through the revolving door, in my arms. Now she was squirming to get down.

Hello, there you are, said my father.

Chairs squeaked as everyone got up.

My sister thrust herself forward. With both hands she pushed her children, ages two and three, toward our father, who had never seen them. But her spontaneity somehow got stuck, like air when you are scared, when my father clumsily maneuvered his legs about. She had not seen him for years. She did not know him handicapped like this. He seemed small now, too, a withered tree, crooked.

Heinz stood at attention next to his chair, bowed awkwardly, rather stiffly. Heinz had always played the part of the outsider in our family, though for me he had a smile and a shy wink. Our mother beamed. She opened her arms to Anita; beneath them hovered the children like little chicks. Anita kissed me, her body warm and round, the scent of her hair and skin familiar. I felt how glad she was to see me, how we really did belong to one another, although we were a decade apart in years and just as far apart in character.

Encouraged by our gestures of overture, she proceeded to embrace our father, Fritz, who, with one hand on his cane and the other seeking a hold on the table, scarcely held up under her vehemence.

Let’s sit down, said Fritz.

My God, Papa, sobbed Anita. My father settled himself in, wiggling back and forth like a dog, and finally sat down on the hard chair.

Finally we all sat down, and my mother, always ready with the appropriate gesture, pulled out all sorts of packages.

You have to wear these in the hot sun, she said, and pulled a red felt safari hat over the head of each little grandchild. Franzi had her father’s broad face and blond hair, sitting on her forehead like a sunny straw roof. Christine looked like I once did, the family found. This must have been why she was so familiar to me, so I took her little hand in mine.

Like a soundtrack to our weighty greeting ceremony, freighted with so many hopes, an airplane droned down onto the landing strip.

That will be our aircraft, said Heinz, like someone who always knew everything, and his eyes followed it until it sank down past the chestnut tree outside.

Heinz twisted round awkwardly, his chin practically resting on the tabletop, to observe the toy landing even more closely. Then, leaning toward my father, he asked politely: How are you doing?

It never gets better any more, only slowly worse, answered my father, and looked past us into the distance. They haven’t found anything and aren’t going to find anything to fix MS. Not in my lifetime. He took a deep breath.

Oh, Daddy, sighed my sister.

Now, for in medias res. Do you speak English already?

No, but I’m learning.

I am glad that my friend Veit can use you in Africa. That is a great opportunity. Great opportunity, he said to himself with a nod. Anita, for you, too. Out there you can raise your children right. I have recommended you highly, in spite of everything, he said quietly, as if he had to forgive himself the generous recommendation. Conflict hovered over the table, a somnambulistic ghost.

Yes, many thanks, thanks so much, said Heinz, bowing and clapping shut at his midriff like a Swiss army knife.

Our mother glanced with a cheerful smile from one person to another around the table. No matter what the atmosphere, she held firmly to the original intent of the reunion. My father looked as if he were practicing drown-proofing, a technique for keeping oneself alive in arctic waters. Survivors of the Titanic reported it: use as little air as possible. “The only motion is a slight lifting of the chin.” My mother, by contrast, practiced what one might call “thick skin.” In the presence of her pessimistic husband she was always in a good mood, which in turn failed to improve his temper.

We ordered weisswurst with sauerkraut. The new Africans in particular were to tank up on sausages and the delicious sauerkraut, since in their quite altered future they were not going to get them any time soon.

You’re thoroughly capable, said my father.

It seemed that what Heinz really wanted was to spring up and stand at attention. He puffed up his chest and winked at my sister. She smiled.

We ate and drank beer and chomped and raised toasts, although beneath the grubby orb of light hovering above our table there hung family pressure. Two factions were firmly stuck in the imperative of their feelings. This family drama, so old, so tired. The parents were still cross with their capable son-in-law. They no longer altogether understood their own reasons, and yet these feelings lingered...disappointment, betrayal, weakness, and love.

Were they cross with him because Anita loved Heinz and not another? But which other? Not everyone could make a marriage as perfect as our brother Uli’s—he had studied brewing and promptly married into a major brewery.

Still, ever since Uncle Veit had hired Heinz, people could sit together at table again. Yes, that much was true. But express one’s feelings? About what? There was nothing one could clearly have named. A ghost hovered there, this inexplicable resentment of my parents’, whose presence everyone felt. The atmosphere affected Heinz least affected of all, for he was the man he had always been. Only in this hour of parting could he really appreciate what for him had been the incomprehensible happiness of going off to Africa with Anita.

My sister gazed expectantly at our father. She waited for a warm word, a kindly glance, a loving gesture—something of her own to take with her into the future.

My father said: Africa. And the word stood there with us.

Fritz had been in the war, stationed in North Africa under Field Marshal Rommel. He was a lousy officer, preferring to shoot the breeze with carpet merchants in the twilight of the bazaars rather than take part in Hitler’s war of conquest. My father and Rommel enjoyed a friendship that saved Fritz’s life, for in 1943, in the midst of the war, Rommel sent him back to his estate in Germany “to nourish the Volk.” The Field Marshal added, “There you will be of more use.”

Africa remained Fritz’s great passion. Always present was his friend Veit, who lived at the foot of Kilimanjaro, having emigrated in 1920—a step my father envied and admired him for.

He turned to Heinz.

Capable is what you are—as if Fritz were repeating his thoughts aloud. This concession was the easiest for him. A fact. He did not use the familiar pronoun with Heinz, never had. They always kept a polite distance. And now a fleeting smile glanced across Fritz’s face, from the eyes to the goatee to the mouth, hovered for a brief moment on Anita across the table, moved over to Christine and Franzi, munching red sausages, their faces red with the reflection of their red berets. The little smile, a shadow of the past, was immediately noted by Adi. She rocked back and forth in her chair, holding the grandchildren by the hand, and sang happily:

| Wiedele wedele | Inside out, upside down |

| Hinter dem Städele | Out behind the town |

| Hat der Bettlemann Hochzeit. | It’s the beggar’s wedding day. |

I held Lexi still, using my foot to pin her leash under the table, since now she smelled the sausages and wanted to get up on the bench.

Yes, yes, Africa, said my father again. Africa was always with us, an aphrodisiac for the temperament, a bowl of punch brewed from the longing for missed opportunities. Africa was sandalwood oil, heat, fata morgana, pools of water, jacaranda-blue streets, pink flamingoes, snakes like tree trunks, screeching apes, the scent of vanilla, a fine tree. Colors, colors, colors. And the ineluctable danger of this wild continent, dictated by Nature herself.

A sudden flash of the upright lamp bathed the room in sepia. Aroma of coffee, sent to us by Uncle Veit. This hour belonged to my father.

The long, thin shadow cast by a spear flits along the wall in oxblood. Disappearing for a moment, it jumps into the rectangle of light at the window. A Maasai watchman squats amid the indigo of the tree-lined wall, and, if one looks long enough, one sees the white of his ornaments lighting up, the warthog teeth, shells, glass, and also the teeth in the mouth of the dog that pants next to him. The guard sits with his back to the house, so that he can rescue himself with a leap if two will-o’-the-wisps burst out at him from the jungle wall.

A leopard? I ask.

Not just that, there are many dangers. That’s why Veit keeps the Maasai warriors as watchmen. Mostly they just sleep, full of bombe, nigger beer. He laughs.

Black-and-white photographs documented Father’s Africa, which he lovingly cultivated, every detail unforgettable. His Africa, which he knew only from the war. The opportunity, missed back then, wove the thread of a dream through his days. Now Anita was going to live the life he had wanted so very much for himself, Adi, my brother Uli, Anita, and me; she was going to live that life.

You will surely do a lot of riding out there, said my father, and Anita beamed.

Yes, that will be our great luxury, said Heinz. We shall see, he added, so as not to seem too happy. In reality both of them would have liked to throw their arms around the neck of this father, this father-in-law, full of happiness and gratitude. But many things stood in the way.

1953. Few people traveled by plane. It felt as if my sister and her family were the only ones flying off into a whole new life.

When the brief reunion and farewell ceremony were over and my sister, sobbing, pressing her children to her bosom, had vanished from our sight, with Heinz, to begin her new future, my father, while he was still staring at the door, said to me and Adi:

Go on up those steps and keep waving to them!

With his cane Fritz pointed to the rectangle of gray sky at the end of a staircase leading up to the visitors’ balcony.

He wanted to be alone.