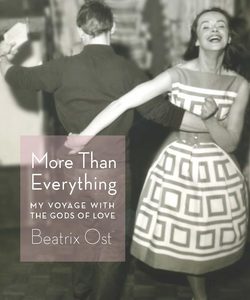

Читать книгу More Than Everything - Beatrix Ost - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Letter-Writer

ОглавлениеTHE STENCH OF COLD SMOKE in the compartment of the train that brings her to a suburb. A crooked, mistrustful little grin is glued onto the face of the uniformed official who snips her ticket.

She has promised Ralf this visit. The two of them are following, chasing something neither of them can name. At first it was an idea, the spark of an ignition, but as they stroll through the little locality, whose foreign streets are sweating in the midday silence, and Ralf accidentally bumps her arm, she is startled.

’Scuse me, says Ralf.

Beneath a cherry tree the pavement is colored red by the mousse of crushed fruit; above them the threatening hum of a bee swarm. In the garden to their left and right blooms flax and foxglove. Above them stretches out the Bavarian sky, blue as never before.

I live there, Ralf says, gestures with his chin at some house, and turns off around the corner.

Against the fence leans a blue bicycle made for a man.

As they arrive at the last house in the village, the view opens onto a field across which, at regular intervals, grain bound up in the form of huts stands out to dry. They leave the path and walk across the stubble, diagonally across the vast field, toward the center. Behind one of the grain towers, where no one can see them, they lie down on the hard ground in the piercing midday sun. She looks about, squints toward the sky. High above her hovers a cloud in the form of a sheep.

The whistle of a returning train tears itself into little shreds above van Gogh’s field. It seems that an eternity separates her from the village and the train station.

I have to get home, she shrieks, jumping up and racing across the tares, between the grain towers, crisscrossing to the path, flitting past the blue bicycle, a whirlwind of color, racing through the tree tunnel with the bee swarm, across the crushed cherries, feeling the grinding pebbles beneath her feet, panting wildly as she reaches the train station.

The train pulls in slowly, a grandiose spectacle of squealing brakes and clouds of steam. On the platform, easily recognizable by his crooked grin, stands the uniformed official who snipped her ticket on the way in.

Now he seems so familiar that she wishes he would climb aboard the train with her and accompany her home.

And from quite far away, from the fields on the outskirts of town, calls the cuckoo. Cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo…

•

It was an unexpectedly cold winter as I turned fourteen. I just had to wait until summer, then I would be finished with boarding school. In the school, Fräulein Sacher and Fräulein Meineke ruled over 120 interned girls, who, like me, lived too far away from Munich. Having grown up in the country, I felt as if I were in prison, but there was nothing that could be done. I absolutely had to go to this strict, refined school. It came complete with mandatory Latin lessons, which my father thought I had the brains for.

In the afternoons there was free time from one o’clock to four. It was winter, so we went in pairs, in groups of three or four, with skates slung over our shoulders, to the “Prinze.” One slunk under the wooden planks of the stands, heard the loud blaring of the music, and already there was the krrr of the skates on the ice, producing expectant excitement within us like a noise machine countering the loud music. In the middle of the arena danced those who could dance well. The others, who were still practicing, or taking lessons, did exercises in the corners.

Clockwise! Keep it orderly or there will be consequences!—bellowed the voice from the loudspeaker when someone went against the stream.

I clambered up onto one of the spectator stands to pull on my skates. A birthday present. Previously I just had owned old-fashioned Dutch-style iron skates, metal screwed onto ski boots; the damned things were always coming loose and bending my ankles. Now, with the superb new white leather skates, I could really cut loose.

Should I help you put on your skates? A voice right next to me.

I looked up and laughed nervously. This is a fellow I have already seen here a few times, I thought, and extended a foot toward him.

Yes, if you like. Then I’ll keep my gloves on.

Next to me the giggling began. My God, a boy had spoken to one of us. An electrifying vacuum took form around us, a total stillness. At boarding school we had been surrounded by only women for four years. When the gardener mowed the playing field behind the school, everyone noticed. Many girls opened windows and watched him, as if he were offering a fantastic pantomime.

The head with the woolen cap bent down and fished for the skates. Let them laugh, I thought, and drew back a little from the other girls.

I’m Kaspar, said Kaspar, and held my foot in his hand. With the other he undid the laces of my shoe to put the skate on me. He laughed like someone who has a plan, who has given things some thought, quietly and privately. I smiled, too, and left my feet in his care. When the shoes were laced, he led me into the ice arena.

With the new skates the skating went much better, and Kaspar called out to me encouragingly.

You can already skate quite well. I have seen it before.

From then on we met daily at the ice rink and whizzed around in a ring to warm ourselves up, and also because in the sheer excitement we did not know what to do other than get moving. At the same time we could touch each other. Words, even thoughts, were too fragile. Kaspar was already 18 and would be taking his finals in the summer.

Soon he was writing me at school, a love letter every day. Fräulein Sacher shook her head: yet another letter for you. I felt the heat of embarrassment as the hand holding the radioactive envelope shoved it across the table. Fräulein Sacher gave me a strict and hostile look, as if the number of received letters were a proof of a conspiracy against the virtue of the school.

As spring approached, Kaspar and I met on the way to my dance class at the Isadora Duncan School, in an ochre-colored villa in the Mauerkircherstrasse, surrounded by a little wall.

Sitting on the stoop, nestled together like two happy vagabonds, we forged a plan. We decided that from now on we would use various female names as senders, also different colorful envelopes. I was impressed by his airtight chess move. My thoughts swirled. Having Kaspar so near aroused me—the powerful lie even more so. When no one was looking, Kaspar pressed me to him and fumbled for my breasts. My hand, a weak attempt to moderate his storming of the fortress, was decidedly pushed aside. He covered every free patch of skin with an invasion of kisses. He called me his little she-goat and said he wanted more, more than these half hours in the ice cream shop, more than the all-too-brief encounters snuck in before and after my dancing lessons. More!

More? I did not know what to think. And so half of my brain, the deposed seat of reason, left the other a free hand.

When I was with Kaspar I felt a completely new helplessness, a kind of lameness that overpowered and entranced me at the same time, so that my will, otherwise so strong, yielded its place to a weak addict. I fished for something I could firmly hold onto, laughed nervously and noted details, like the lentils left behind in the fairy tale to show the way: a beetle with enameled tuxedo wings, how he worked his way up the stem; a blister from overly tight sneakers on the top of my bare toe; a crow, black, near the path, with an open beak, as if it wanted to call out something to me; my middle finger, blue from writing. I was almost struck dumb, as I did not want him to know how much I did not know, and nothing was to remind him that I was still a child.

In this diffuse state of mind Kaspar seemed more present than I did myself. He was obsessed with a particular idea, and nothing could hold him back from translating this idea into reality.

Kaspar wrote my parents a letter—purportedly in his mother’s name:

Dear Mrs. Ost,

My daughter Petra has made friends with your daughter Beatrix, and with your permission I would very much like to invite her to spend next weekend with us. I live in the Berlinerstrasse, which is quite easy to reach with the #9 streetcar, in the same quarter as the school. My husband is a research physicist and unfortunately still detained by the Russians on Krim Island. So I live alone with Petra. We would very much enjoy a visit from Beatrix.

With warm greetings,

Margarete Busch

My mother was happy. I was to spend a weekend with the charming Petra. She wrote Fräulein Sacher that I was allowed to visit Frau Busch, an ersatz auntie, anytime. Adi was never mistrustful. She did not believe in lies. She would have felt it a waste of time to spy on her teenage daughter. She was firmly convinced of the goodness within every human being.

And so it came to pass that my good, clueless mother played the role allotted to her in the general melancholy of adolescence, when one phase of life has just ended and the other is just beginning. Had she had the slightest inkling, she would have turned into a beast in fear for me, and yet the huge, hard lie, shamefully red, flowed away and watered itself down in Kaspar’s presence, a tender gray at first, until finally it existed no more.

Kaspar’s father stared down from the wall next to the door of Kaspar’s room, with a direct, questioning gaze. He had never returned home from the Crimea. He was in uniform and held his officer’s cap firmly lodged beneath his arm. What little hair remained on his head had slipped down almost to his neck. Beneath the photo stood an old sofa, upholstered in pink damask. A moss-green army blanket was loosely tossed across the seat. This green blanket formed an air pocket between the cushion and the back, which called forth within me a sensation from my childhood: the canopy from my parents’ open feather bed, into which I crept to hide as a child. In that narrow space, which only let in a little air, to which the eyes only slowly grew accustomed, I heard from afar my mother’s voice calling, dampened by the featherbed. I could lie, say I had not heard her, and remain in my hiding-place until my own breath made it so unbearably hot that I would open the featherbed and thereby betray my whereabouts. Innocently, so to speak.