Читать книгу More Than Everything - Beatrix Ost - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

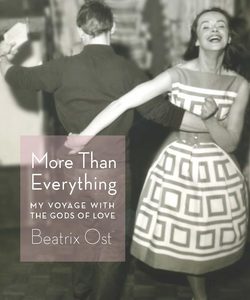

The Bird of Paradise Dress

ОглавлениеOUR HOUSE WAS ANCIENT, as old as a citadel, 500 years old, with walls a meter thick. One of our forests surprised you with the quarry from which the buildings and stables had been built. On the way there, black evergreens pressed closely together, above blueberry carpets so soft that the rain seemed to hover above them. Primal wild boars took swamp baths in puddles. We children held hands until we came to the edge of the ravine. All varieties of moss grew on the steep walls. Generations of snakes and salamanders. Tree stumps, if one bumped into them, dissolved into dust. Jackdaws nested in stolen nests, crows lifted off from the thick underbrush with hysterical cries. Anthills, rust-red, revealed themselves among ferns, growing there in the eternal twilight since the dawn of time. The impudent laughter of a fox.

In the entrance hall of the house, the ceiling was domed, carried on columns. Small medieval doors with iron handles led on one side into several low-ceilinged rooms; as if the rural contractor had reconsidered, the rooms opposite were higher, the windows larger, broader.

In the cruciform-vault kitchen there stood, once a month, a gigantic wooden trough in which the dough for the month’s bread fermented overnight. There I could lie on the broad windowsill—it was almost a meter across—as if on a throne, and follow all the doings on the farm.

As soon as my sister was finished with the convent boarding school and came home, finally free, away from the nuns, my parents thought about marrying her off. Not that anything was said.

My mother’s gaze followed her lovingly and critically. My sister was rounded, wide-hipped, simply full-figured. Her skin was polished, the color of olive oil. I had hair, Anita had “The Hair”: black, shiny as lacquer, great quantities of it, which she wore woven into a wide, heavy braid at her neck. Sometimes it fell down her back to her waist like a horse’s mane. She looked very much like our mother: fine, slightly bent nose, large, heavy-lidded eyes, brows like swallows’ wings. She was very beautiful, and one had the urge to touch her. Even an eight-year-old like myself could feel that. I also felt that what in my mother was agility and mobility, my sister wore as a weight; this species of Mediterranean melancholy, which suited her exterior, and, in this family, belonged only to her.

I observed my family from the lucky position of being the youngest. I knew how my mother cared for Anita. I, by contrast, was left in peace: that one, Beatrix, you can raise, said Fritz to Adi. That became a catchphrase.

I was an old child. Yes. I studied everything around me very carefully. I could do it at leisure, as I was mainly left to my own devices. With my braids woven into a crown around my head, with a steep critical cleft between my eyebrows, I caught wind of many grownup matters and formed my own opinions.

My mother took particular care of Anita’s body. That was simpler. Her spiritual condition was more difficult to grasp and to decipher. Mother, Anita, and I drove into town for massages. The massage was supposed to give her impetus and somehow change her. But as soon as she sat upon her horse, anyone could see that she already had a healthy share of will and drive. Probably she just did not feel like doing anything other than riding.

My sister mounted her horse and had it under control like no one else. She had grown up with ponies. As soon as she outgrew one horse, my father would give her another, larger and more powerful. At present she rode an Arabian gray, Bella. They had a deep connection. Sometimes she came home from a ride with her face scratched up, though she seemed not to notice.

My God, child, did that creature take off with you? my mother called out in a concerned voice.

No, Anita gestured dismissively. She just hadn’t ducked fast enough to avoid a branch. She so enjoyed riding through the forest, on the soft mossy floor, between the high evergreens. Then she gave Bella the spurs and scurried up a bank, a little heedless. One saw her in the twilight, storming toward the farm at a gallop. Bella with Anita, half-human, half-horse. They seemed to be more in the air than on the ground. One heard the stomping of the hooves, the snorting, the groaning of the saddle leather. She flew high, sank back down, tossed upward, pressed downward, relaxed, free and compelled; clumps of earth flew about, a bird fled from its meadow nest with a long cry. The heron hurled himself from his post into the water. Anita was at the gate. Beneath her saddle Bella had worked up a foam of sweat. Bella’s nostrils were flaring. Both were relaxed, dissolved, and the melancholy was extinguished from Anita’s face. Not a trace of it. Her body strong and lithe. She was happy.

But nobody was asking about happiness yet. The war, that monstrous war, had after all only been over for a few years. For happiness, something elemental would suffice—like “getting out alive,” or “a roof over your head,” or “a job.” My mother’s cares were not exactly definable, but they surely had to do with some sort of happiness that she wished for her daughter Anita.

Sometimes a young man rode into the courtyard to fetch my sister. She would straightway saddle up her Bella and ride off with him through the gate, into the lane, veering onto a path across a field, with her still waving; we, too, until suddenly both had vanished from our view.

That is the new veterinarian, said my mother with that certain look.

He is too lame, said my father.

She’s got to get out of here, said my mother.

Fritz and Adi stood there, wrapped in their thoughts. Father, tall and slender, a garland of gray locks at his neck. Wrinkles of strictness, and others etched by laughter, crisscrossed his face. He wore leather knickerbockers, a Bavarian jacket, a green vest underneath.

He wore his sorrowful mien. Anita ought to make a good match, marry a rich man. The opposite of what they had done. Their love had maneuvered them through thick and thin. The thread from which they wanted to weave Anita’s happiness was drawn from the cloth of their love. That, too, they had forgotten, as if there were a new definition of happiness, as if love had been abolished.

Amid our frequent round of guests, my father was proud of my sister. He trusted she would make a coolly considered marriage. He had wanted that for himself, just as he did for Anita. After what we had all been through, money and success were more important. One could not yet properly imagine romanticism. It gave my father a certain pride that people wanted so much to touch my sister; she carried the dowry of Nature with her like a birthright.

The catch was that only a horse-lover could get along with her, since she had no other passions. This immovability made my father impatient—in fact, irritable. To lighten the atmosphere, people would make jokes about it. One of these jests became a household pun: “If only you’d married Schecker Pauli…” The imaginary Schecker Pauli has lots of money, but the girl does not want him, so she has to go through lots of unpleasantness. And again and again, when someone was hard up, it came as if shot from a pistol: “If only you’d married Schecker Pauli…”

The nineteenth century ended in Germany in 1945. In bourgeois families like ours the rebuilding brought new circumstances, new social structures. This was approached with great skepticism and adopted only hesitantly. My parents were appalled by what the war had brought about. Where were their friends’ sons, the sons of the neighbors in their set? The war had torn a huge hole in the age group eligible as potential suitors for Anita. All that chaos. Amid the industriousness of the rebuilding, one again and again ran up against the sordid disorder and bestial plunder the war had caused in every part of our lives.

Another young man, Axel von Bohnin, a distant relative of Aunt Esther, dwelt in her run-down moated castle, together with her twenty Schnauzers. American officers inhabited one wing, which still somehow held up, while the rest of the medieval building, which seemed to be sinking toward the water lilies and into the moats, greeted us with a deeper bow upon every visit to Aunt Esther. The overgrown stone walls enwrapped the castle like a tired snake.

We heard the humming of a motor even from a long way off; it was still a great rarity. An American vehicle driven by a friendly officer brought Axel von Bohnin to our place to have tea while the officer was passing the time fishing in Father’s waters.

Naturally my parents thought Axel came because of Anita. My mother sat at the table in the den. The tablecloth, at which she sewed in golden cross-stitches, fell like a second skirt across her lap, her feet, onto the floor. My father stood at the window, a cigar between his index and middle fingers, and observed Axel sauntering up to the house. He had supposedly been unfit for service. In what way unfit? That they could not quite ascertain. Although my father condemned the war and called Hitler the most fearsome catastrophe that had ever befallen Germany, there was something deeply military in his own manner, in his upbringing. “Unfit for service” was a stigma, somehow.

Maybe he’s got something in him after all, my father observed.

My mother glanced up from her embroidery hoop.

He is from a good family.

The dogs barked. Axel walked beneath the trophy antlers into the room. With him, Kafka’s “spark of a possibility.” As my sister, who had been sought everywhere with whistles and loud calls, finally stood in the doorway, the antlers above her, this spark was extinguished.

Axel had joined my mother on the bench, taken the needle out of her hand, and started embroidering away with the greatest relish, golden cross-stitch after golden cross-stitch.

Which came first? My sister became an expert in dealing with parental expectations.

•

To rouse the sleepy band of lads who worked on our farm, my father had hired a young former officer as manager.

Heinz Seifert came from Saxony; it came through right away in his accent.

Military career? asked my father.

Ja, cavl’ry.

Do you have any clue about agriculture? my father wanted to know.

No, only horses. But I learn very fast. My mother sewed gloves, my father is dead. I worked my way up from zero, the military was my big break.

Astonished by this openness, attracted by the direct gaze, convinced by his attitude—“one can learn anything”—my father hired him.

Jawoll, said Heinz Seifert, and clicked his boot heels together. He was more stout than tall, with wide shoulders, an open Slavic face. He came across as bigger than he was, owing to his upright, rather stiff posture. Like someone who is concealing something but wants to give you the impression of having said everything, he looked with his clear blue gaze directly at his interlocutor, eye to eye. Very soon he had convinced my father of his competence.

My father stepped forth from the gate and tenderly gazed across his land. He saw Heinz out there on his horse, giving the lads instructions. Or was that him on the haymaker, bobbing up and down in the flickering afternoon heat? My father walked part of the way, propped on his cane, toward the scent of the fields, behind him the smoke flag of his cigar. His feet gestured enigmatically. At times they ran like thoughts, with no control, sideways; sometimes they did not want to move at all, which made his step appear delayed.

Fritz had had everything under control. The people who worked for him, the potato cultivation, the team of horses—often one believed he controlled even the weather. When he looked up to the sky to map out the next 24 hours with the aid of a cloud formation: always correct.

Now he looked upward, but the sky seemed to disappoint him. The seedbeds that grew in rows over by the creek were too far away. Someone had to be sent down there to bring him a report.

Fritz stood on the packed dirt of the road, alone, isolated from the life-energy of the others. Old he still was not. A woodpecker loudly pecked Fritz’s anxiety into the bark, quite nearby. Tack tack tack tack tack. Would they find him if he hurtled down the steep embankment at the side of the road? he wondered. His dog jumped high up on him in greeting and he seemed frightened half to death.

Over there, across the field, by the heads of cabbage, he saw the rider, Heinz, changing from a trot into a gallop.

It seems to Fritz that he himself is on his steed. He hears behind him the rushing, roaring and pressing of eighty stallions, driven from their stalls, fleeing the insane fire and smoke, following him. He feels their breath, hears the anxious clip-clop of their hooves, the cries of the lads that hold the horses together. He rides on ahead, behind him a red wall of fire. And yet he himself is calm. Duty gives him strength. He does not feel the hard ground; it seems to him as if he is hovering along the brook toward the rescuing meadow, a little further; behind him rush the snorting creatures; already he reaches the pasture fence post, the big pasture, the opening. He rides through and sweeps out a broad arc in the corral, brings them all to safety.

Lost in thought, he wandered some distance down the gravel road, then, as if he had forgotten something, came to an abrupt stop, looked once more far out across the flat country, squinted, puffed on his cigar, turned and went off, slowly, with short, careful steps, back toward the farm buildings. He felt unusually tired. As for the man who had set out a short while earlier—he scarcely still resembled him. Those were the signs.

The mysterious illness that had seized control of his legs was later diagnosed as multiple sclerosis. No one talked about “the illness.” Fritz forbade it. He hated being ill. He was not ill.

Him I can rely on. Immensely diligent fellow, said my father, meaning Heinz, out there in the field. That he could ride so well also pleased him.

Reliable fellow.

My mother nodded, happy that her Fritz had someone at his side.

And so it came about that Heinz often sat with us at table.

•

My sister wove a red ribbon through her braid.

The bird of paradise dress. I would never forget this dress of my sister’s. Was it the yellow of sunflowers, or a yellow that lights up from autumn leaves, or in the evening sky? No, it was saffron, deep yellow, as one knows it only in exotic plants. On the saffron background of the silk, blue and emerald-green birds of paradise with feathered trains capered about beneath palms. In one’s hand the silk had an exotic tenderness. My mother had got hold of a piece of this fabric in exchange for comestibles. Even many years after the war, barter helped circulate the most wondrous goods.

First came the red ribbon in her hair, then my sister wanted pumps. She skipped down the stairs on tiptoe to practice.

When, please? she asked impatiently.

Buying shoes meant a trip into the city.

With the urgency and attentiveness that Anita otherwise mustered only during the purchase of a saddle or bridle, the tailor was scheduled into the house to sculpt the exotic fabric. The dress was built like couture around Anita’s body; when the stitching was finished, it hugged her figure, the sleeves ruffled at the elbow, plissé pleats resting densely on her breast, down to her waist, the skirt reaching almost to the ankles. Standing on her new pumps, Anita looked insanely beautiful.

I knotted Father’s necktie about my thin waist, above a dress my mother had brought from Bulgaria. It too was silk, ruffled at the shoulders, embroidered with little cross-stitches. I found myself beautiful too.

In his free hours Heinz Seifert sat at the edge of our garden, under the weeping willow, or at the corral, leaning on a post with a book in his hand. One hour every day for continuing education.

Anita and I joined him.

Are we disturbing you?

He told us about the war. Male episodes. About insoluble situations he had solved. We nodded. He told of the rain that the sun gathers back in again. Of the logical sequence of events in nature.

The rainbow is the bridge of the gods, he said.

Beautiful, said Anita, and smiled.

He read us a poem he had just written for her.

Read it again, said my sister, her face red, and gazed out past him, at some place far away, in the dark ribbon of woods. Anita looked at her hands, which rested. one atop the other, on the fence post, brown and soft, muse’s hands, with no veins, with finely tapered fingertips. She looked down to the molehill a mole had freshly heaped up just a little while earlier, before we had met at the fence. She looked at her feet in the open sandals, soft, round, and brown, siblings of her hands.

What had he said?

I lingered close by, neither invited nor sent away. I felt the weight of this meeting.

Are you one from the meadow, one from the garden

In the bunch of flowers in my hand?

he had asked in the second verse. Anita smiled. His deep voice sounded strange and new to her, like something neither of us had yet heard, like the purring of a motor in the concert round about us, yes, like the automobiles that now and then interrupted the music of rural life. From quite far away, behind the fields, behind the forest, we heard the cuckoo cry “cuckoo, cuckoo”.

Heinz stood before Anita, not tall, only a little taller than she, his wide Slavic head leaning to one side. Earnest. When he read, and then looked up from the page, his eyes swept her in, like a butterfly net. The bumblebee that buzzed around him, the scarab beetle that struggled its way up his collar, melted in with the panting dog in the grass. Heinz’s presence possessed a vehemence that Anita could not explain. Drops of sweat gathered on his brow. He fumbled for his handkerchief and Anita was frightened. The butterfly net lifted itself, the loud meadow sang and chirped, it buzzed, the dog panted.

Anita! Anita! came the voice of my mother floating over to us. I went running off.

Are you one from the meadow, one from the garden came the afterbuzz.

Anitaaa! Can you fetch parsley?

Yes, she called, cried: Yess!

A glance back. Heinz had disappeared. The fence enclosed the meadow; the shadow of the trees lay, blue, between house and pond.

•

With Heinz among us we had a coachman again. It was superb to sit between Anita and Heinz up front in the wagon. The soft body of my sister on the one side, on the other Heinz’s taut muscles, the strength of his energy. Now many things were easier. One no longer had to force Anita to go for a massage. In the village, in front of a shed behind Mrs. Hagenreiner’s colonial goods store, we tied up the horses and waited for my sister. Heinz and I sat on a little wall next to the rabbit hutch. The rabbits jostled at the wire door, pressed their noses through the spaces between the wire meshes, to nibble at the blades of grass I pushed through to them. There was grass in the courtyard between the wagon tracks. I looked vainly for lions’ tooth. That is what they would have liked most. But then I slipped back closer to Heinz, to listen to him. He explained to me how the horse holds energy in its breast to pull the wagon. How the legs elegantly play into the musculature at a canter and at a gallop. How the carriage is a clever invention, merging with the horse into a greater whole.

Although I was the only one in the family not interested in horses—on the contrary, I was afraid of them—it was quite splendid to know Heinz’s attention was fully concentrated on me. This present made me a trusted ally. When on a carriage ride, I sat in the middle and felt at my back how Anita and Heinz held hands. Then I got to hold the reins. I bent forward and observed with playful attention the muscles on the hindquarters of Janosh and Bella, to please Heinz.

As soon as we reemerged with our coach from the loyal shadow of the forest, saw our farm further off as a chess piece standing on the orderly board of the fields, Heinz and Anita fell away from one another, like the pages of an opened book. Heinz took the reins once again, and I leaned back again into the mysterious middle.

My father liked to chat. He liked it best when as many people as possible listened to him. In order not to have to admit his weakness, Fritz called it talking shop. And this was why Heinz had come to sit with us at table. The other farm hands ate in the big dining room near the kitchen. There, there was loud smacking of lips. Dipping of bread in milk. Belching. Loud slurping of soup. Everything that was forbidden us at table. Heinz sat opposite me, as guilty as any of them.

My mother’s gaze did the rounds critically. Beatrix! Fork to mouth, not vice-versa! No shoveling it in! she said unambiguously. Heinz felt this addressed to him, too.

Well, how is it? he asked me, to unburden himself of his embarrassment. He propped the elbow of the hand that guided the spoon to his mouth on the table and bent down to his plate. His hand trembled a little. He avoided looking at Anita and concentrated on my father’s utterances, which amidst the dining ceremony changed subjects with unexpected quickness, shooting out like blank cartridges.

It was a game: Heinz against my impatient father. Heinz stimulated my father above all because he gave him his entire attention. And Father liked to eat and make conversation, in both cases with great relish.

Heinz came from Saxony, from a village near Chemnitz—my mother’s family also came from Saxony. My father liked to tell the story of my Saxon great-grandfather, Arved Rossbach, a tall, dignified, very good-looking man who had built many significant buildings in Leipzig and Dresden at the end of the nineteenth century: the opera house, the railway station, the chancellery, banks and villas. My mother had gone visiting there as a young girl.

All of it destroyed by the Russians in the war, said my father. Now they have changed their mind and are proud of Arved, because of his communitarian convictions. He built the first workers’ housing estate with running water and toilets. 1900—think of it.

The conversation leaped like a ball from my grandfather to Old King Fritz to the Meissen porcelain we ate on every day—my mother had inherited a banquet setting for 24 people. Then it veered off onto the Saxon landscape. This Heinz knew very well. He nodded in agreement.

Flat, the land is very flat, said my mother, and looked out the window to picture it to herself. The flatland. All the way through to the chalk cliffs on the island of Rügen, which once belonged largely to my family, to Arved Rossbach’s forebears.

Yes, they were very wealthy, said my mother. She drew herself up in her chair and had to smile.

Heinz perhaps reflected that he had forebears, too, but no one cared a fig about them. Least of all he himself. Not worth mentioning. And, as if my father had read Heinz’s thoughts, he bent down to him in a friendly way, with genuine interest.

Didn’t you say your mother sewed gloves for a living? Hmm, that’s a tough row to hoe.

Yes, we were very poor, said Heinz with a laugh. He laughed, because he was thinking about what he was going to say next. Poor? Back then, when I was growing up, we were poor. Not any more. Each week I send my mother in East Germany a care package with coffee, wool, aspirin, and silk stockings, and she can barter things for them. By their standards she is not poor any more. There is not a lot to buy among the Russians, but one can barter for help and many other things. A real black market is in bloom out there.

He laughed even more, this time about his luck at being here in Bavaria. As he did so he twinkled at me. My sister was silent. She petted a dog that was begging, under the table, on her side. Her whole attention concentrated itself on Father. She chewed slowly, looked around the table, petted the dog again, and when the conversation turned to horses, then and only then did she join in, always addressing Father, since it pleased him.

Apropos the Russians, my father said. Max Rossbach, Arved’s oldest son, my wife’s father, who of course grew up in Dresden…Anyway, Max went to the Russian school in Dresden. At the time that was very unusual. He spoke fluent Russian.

Heinz nodded. He was already in the picture when it came to family history.

Yes, my father continued. In the 1914 war, Max received a special captain’s commission because of his language skills. He was to turn up at the German-Swiss border. There he received his orders with his platoon, about twenty men, to take over a sealed train and accompany it all the way across Germany. At every stop his platoon had to swarm out in formation, to secure the train under the heightened conditions.

My father took off his glasses, raised his eyebrows and looked across the table to his wife, who embodied that cross-section of humanity that has no clue about the rules of war. Heinz had long since given a nod of agreement.

“Heightened conditions” means firing your weapon immediately, should the sealed car open, for instance, or someone approach. In Sassnitz, on the island of Rügen, the train was handed over to Swedish military personnel. So. Max found out only much later who was in the train. It was Lenin, who, in the event of an escape, was to be addressed in Russian and arrested. Lenin, who had emigrated to Switzerland in 1901, was now being shipped back to Russia with German help. Once he arrived there, he toppled the Kerensky regime—naturally it had all been prepared in advance—triggered the October Revolution, and became head commissar of the Supreme Soviet and founder of the Soviet Union.

That’s all gone down in history, said Heinz. Unthinkable that Lenin might have gotten loose in Germany.

I see you are no Communist, said my father contentedly.

He went to the bookshelf, looked along the rows, pulled out a book—Broaden your horizons, young man!—and pressed Nietzsche into Heinz’s hand.

Heinz was a superb listener, Father a superb storyteller. Thus they formed a sort of alliance, a mutual dependency, a symbiosis. What one wanted to unload, the other eagerly sucked in. A good listener seduces the narrator. The seduction is as intimate, quiet, unannounced as love itself. The listener makes the narrator reveal a great deal of himself—perhaps everything. The narrator goes into a wonderful intoxication that leaves him blind. Deaf too.

Thus Heinz became our family’s familiar.