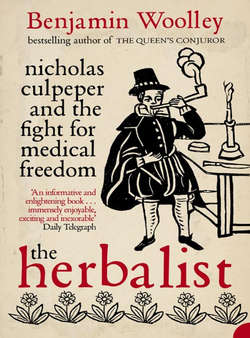

Читать книгу The Herbalist: Nicholas Culpeper and the Fight for Medical Freedom - Benjamin Woolley - Страница 6

TANSY Tanacetum vulgare

ОглавлениеDame Venus was minded to pleasure Women with Child by this Herb, for there grows not an Herb fitter for their uses than this is, it is just as though it were cut out for the purpose. The Herb bruised and applied to the Navel stays miscarriage, I know no Herb like it for that use. Boiled in ordinary Beer, and the Decoction drunk, doth the like, and if her Womb be not as she would have, this Decoction will make it as she would have it, or at least as she should have it.

Let those Women that desire Children love this Herb, ’tis their best Companion, their Husband excepted.

The Herb fried with Eggs (as is accustomed in the Spring time) which is called a Tansy, helpeth to digest, and carry downward those bad Humours that trouble the Stomach: The Seed is very profitably given to Children for the Worms, and the Juice in Drink is as effectual. Being boiled in Oil it is good for the sinews shrunk by Cramps, or pained with cold, if thereto applied.

Also it consumes the Phlegmatic Humours, the cold and moist constitution of Winter most usually infects the Body of Man with, and that was the first reason of eating Tansies in the Spring. At last the world being overrun with Popery, a Monster called Superstition perks up his head … and now forsooth Tansies must be eaten only on Palm and Easter Sundays, and their neighbour days; [the] Superstition of the time was found out, but the Virtue of the Herb hidden, and now ’tis almost, if not altogether, left off.*

Tansy has a tall, leafy stem, two or three feet high, with ferny foliage and flowers like golden buttons.1 Maud Grieve describes it as having ‘a very curious and not altogether disagreeable odour, somewhat like camphor’. The name probably comes from the Greek Athanaton, meaning immortal, either because it flowers for so long, or because of its use in ancient times to preserve corpses. It was said to have been given to Ganymede (‘the most beautiful of mortals’, carried off by Zeus to Olympus to serve as cupbearer and catamite) to make him immortal.

The herb was long associated not only with immortality but birth, hence the link with Easter, when, according to Grieve, ‘even archbishops and bishops played handball with men of their congregation, and a Tansy cake was the reward of the victors’. Richard Mabey, echoing Culpeper, writes that its original medicinal use at Easter time was to counteract the ‘phlegm and worms’ arising from the heavy consumption of seafood during Lent.

Though tansy has a strong, bitter taste, the cake was sweet. According to a traditional recipe, it was made by adding to seven beaten eggs a pint of cream, the juice of spinach and of a small quantity of tansy pounded in a mortar, a quarter of a pound of Naples biscuit (sponge fingers similar to macaroons, but made with ground pine nut kernels rather than almonds), sugar to taste, a glass of white wine, and nutmeg. The ingredients were combined, thickened in a saucepan over a gentle heat, poured into a lined cake tin, and baked.2

A dark, gnarled yew stood next to the lych-gate, poisoning with a drizzle of noxious needles anything that grew beneath it. Rose bushes still in flower were scattered across the graveyard, planted, according to local tradition, by the betrothed on the graves of their dead lovers. A mound of fresh earth marked the spot where, a few days earlier, Maurice Sackville, the late rector of Ockley, had been interred. This was the scene beheld on 15 September 1615 by the Revd Nicholas Culpeper, Sackville’s hastily-appointed successor. He had arrived just four days after Sackville’s funeral from his old post as vicar of nearby Alciston. He was in his mid-thirties and, for a country parson, uncommonly well educated, boasting a degree from the University of Cambridge.3

Ockley was a modest but busy parish on the border of the counties of Surrey and Sussex, straddling Stane Street, the Roman road that still acted as the main thoroughfare from Chichester on the south coast to London. The church itself was a quarter of a mile from the village, perched on a hill, next to the remains of a castle and Ockley Manor, owned by Nicholas’s cousin and patron Sir Edward Culpeper.4

Nicholas and Sir Edward were from branches of the same family that was joined three generations back, part of a voracious dynasty that grew like white bryony through the counties of Sussex, Kent, and Surrey. The origin of the Culpeper name is obscure. Some have speculated that it derived from the place where the first family members settled, perhaps Gollesberghe in Sandwich, Kent or Culspore in Hastings, Sussex. To most, however, it was more suggestive of politics than geography. ‘Cole’ was a prefix meaning a fraud, as in cole-prophet, a false prophet, or ‘Colle tregetour’, a magician or trickster mentioned by Geoffrey Chaucer in his poem The House of Fame.5 Colepeper, one of innumerable spellings, would therefore mean a false pepperer, someone trading illicitly as a grocer outside the Fraternity of Pepperers, the guild incorporated in 1345 which later became the Grocers’ Company. Or the ‘pepper’ could simply refer to the herb’s association with offensiveness. Jack Straw, a supposed leader of the fourteenth-century Peasants’ Revolt, was described by a contemporary writer as a ‘culpeper’, meaning mischief maker.6

Elements of the family had certainly lived up to this interpretation of the name. Wakehurst, the family’s main seat in Sussex, had come to the Culpepers after the daughters of its original owners were abducted by brothers Richard (1435–1516) and Nicholas (1437–1510). A grandchild of their elder brother John, Sir Thomas Culpeper, was beheaded in 1541 for treason, accused of being the lover of Catherine Howard, Henry VIII’s fifth wife, herself the daughter of Joyce Culpeper, Thomas’s sixth cousin, once removed.

By the early seventeenth century, the leading Culpepers were eager for respectability. Edward Culpeper, the current occupant of Wakehurst and the great-great-grandchild of Richard, had risen to become a Sergeant-at-Law (a high-ranking barrister). But in those days, lawyers, like physicians and merchants, were not considered gentlemen. Titles and land were the real currency of social rank, and Edward was ruthless in his pursuit of both. In 1603, he bought himself one of the new knighthoods that James I sold on his succession to the English throne in order to finance an opulent court. Through legal action as well as acquisition, Edward also enlarged his estate at Wakehurst into one of the most extensive in Sussex, and built an impressive mansion in the middle of it to show off his new-found status. Among the many lucrative plots for which he litigated was one of 120 acres at Balcombe, on the south-west border of his Wakehurst estate. This had been the principal possession of the Revd Nicholas Culpeper’s grandfather, leaving that branch of the family incurably reduced. Nicholas had inherited just £120 on his twenty-first birthday, enough to pay for his education at Cambridge University, where he received an MA in 1608. Thereafter he was dependent on the patronage of Sir Edward.

Now, as rector of Ockley, entitled to the living or ‘benefice’ generated by local church taxes, Nicholas could look forward to a comfortable, if undemanding, life. He had also become engaged to Mary, the twenty-year-old daughter of another rector, William Attersoll of Isfield, a village near Nicholas’s old parish of Alciston and within the same deanery or church administrative district.7 A month after Nicholas took up his position at Ockley, they were married at Isfield.

Nicholas’s first few weeks in the parish were busy with funerals. Coffin after coffin was carried past the old yew into the church yard, six before Christmas, a high number for a village with a population of a hundred or so. One of them contained Katherine Sackville, wife of the late rector, suggesting that both had succumbed to a disease passing through the village. Nicholas must have been concerned about the infection lingering in the rectory he and his new wife had so recently occupied.8

Within the year, Nicholas too was dead, around the time of the first anniversary of his marriage to Mary, who was about to give birth to their first child. There is no record of what killed Nicholas, but there was a ready supply of possible causes. At around this time, the practice began of hiring old women – ‘ancient Matrons’ – to roam parishes as ‘searchers of the dead’, recording the number and causes of death for regularly published ‘Bills of Mortality’. There was some controversy about this practice. According to John Graunt, who started analysing these figures in the 1660s, people questioned ‘why the Accompt of Casualties is made’, since death was a divine, not a demographic, matter; its time preordained; its cause the instrument by which God’s will was performed. No intervention, physical or otherwise, could prevent it. ‘This must not seem strange to you,’ advised William Attersoll two years before his son-in-law’s death, ‘for the whole life of a Christian should be nothing but a meditation of death … You must consider that nothing befalleth us by chance or fortune, all things are ruled and guided by the sovereign providence of almighty God.’9

Despite qualms about the searchers’ work, they were diligent in their efforts and came up with an elaborate catalogue of causes: apoplexy, bleach, cancer, execution, fainting in the bath, gout, grief, itch, lethargy, lunacy, murder, palsy (paralysis), poison, sciatica, and ‘suddenly’. But one class of cause prevailed over all these: infectious disease.

There was no concept of germs in the seventeenth century. Infection was a corruption of the air, a humidity or ‘miasma’ that exuded from the earth, a theory that lingers today in the belief in the benefits of ‘fresh’ or ‘country’ air. Some places were more prone to infection than others because they were near sources of this miasma, such as sewers and swamps. London, with its cramped streets, fetid streams, and cesspits, oozed contagion. But the countryside could be just as dangerous. Some settled rural populations – for example in remote parts of the West Country or on the chalk uplands of the Sussex Downs – had high levels of shared immunity to native bugs and lack of exposure to foreign ones. A village such as Hartland in Devon enjoyed infant mortality and life expectancy rates so low they would not be matched nationally until the 1920s. But other areas were as bad as any urban pesthole, notably large tracts of Sussex and Kent. ‘Marish’ and estuarine terrain, alluvial tracts, swampy low-lying basins, and sluggish rivers were suffused with ‘marsh fever’ or the ‘ague’ – malaria (from the Italian for ‘bad air’). The disease was familiar, and its diagnosis precise, categorized according to the frequency of the feverish attacks that announced its onset: daily (quotidian), every other day (tertian), and every third day (quartan).10 The convulsions produced by marsh fever, though distressing, were not usually fatal. However, they left sufferers more susceptible to enteric diseases – gut infections such as typhoid and dysentery. These were less clearly differentiated, but more deadly, frequently killing off one in ten of the population of a village in a single year.11

Just such a crisis seemed to overtake Ockley in 1615 and 1616. Autumn was the killing season for enteric infections, and nearly all of the twenty deaths in the parish during those years occurred between September and December. The summer of 1615 was particularly hot, and the stagnation of water supplies and sewers produced an epidemic of typhoid across the region.12 Perhaps it was this that carried away Nicholas Culpeper. If so, the sickness would have taken three weeks to pass through its elaborate pageant of pain: innocuous aches at first, possibly accompanied by nosebleeds and diarrhoea; a fortnight or more of high fever and skin rashes, interrupted by brief remissions. This was the first phase. The second was a week of tortuous stomach pains and delirium.

If he was in this state, very little could be done for him. Mary would have been expected to mix up some palliative medicines, based on recipes she had learned from her mother, or from local women with more experience. Typical remedies known to soothe the symptoms of fever were flowers of camomile beaten into a pulp and mixed with cloves and vervain, to be applied, as one herbal unhelpfully reported, according to ‘mother Bombies rule, to take just so many knots or sprigs, and no more, lest it fall out so that it do you no good’.13

A local ‘wizard’ or ‘cunning woman’ may have come to call. Bishop Latimer had noted in 1552 that ‘A great many of us when we be in trouble or sickness … run hither to witches, or sorcerers … seeking aid and comfort in their hands’.14 They were still a part of life in rural villages such as Ockham in the early 1600s, promising with remarkable assurance that they could heal a variety of ailments using a combination of magical rituals and semi-religious invocations or spells. Techniques included burning or burying animals alive, immersing sufferers in water flowing in a particular direction, dragging them through bushes, or touching them with a magical talisman or staff. Such methods were justified on the basis of no particular medical or magical theory, though many were inspired by the principle of sympathy – the idea that one thing (such as a disease) had an affinity with another that was similar or connected to it in some way. Thus, to cure a headache, a lock of hair might be taken from the victim and boiled in his or her urine.15

However, the Revd Nicholas Culpeper was very unlikely to have allowed such people near him. Their superstitious practices were closely associated with witchcraft, and a Christian minister would have considered them either fraudulent or diabolical. Mary’s attitude may have been different. She was still a comparative stranger in the village, having been in the parish for little more than a year, and was heavily pregnant, expecting to give birth any day. In such a state of isolation and vulnerability, as Nicholas lay unconscious on his sickbed, she may have yielded to the temptation of letting a charismatic healer through the rectory door.

She may also have called for a doctor, though his chances of success were little better. The nearest large town, Horsham, was ten miles away, and the county town of Guildford a further five, so it would have taken some time and cost for him to come. Had one been summoned, his most likely treatment during the feverish stage of the illness would have been bleeding and purgation – in other words letting blood from the arm and prescribing toxic herbal emetics and laxatives to provoke violent vomiting and the evacuation of the bowels. Mary would have had to administer these medicines both orally and anally according to a strict timetable, and they would have intensified her weak husband’s sufferings, forcing him to endure hours spending blood into a basin, retching over a bucket, and squatting on a chamber pot, until he was finally overcome.

The Revd Nicholas Culpeper was buried in his own graveyard on 5 October 1616. Less than a fortnight later, at 11 p.m. on 18 October 1616, in the dark of that dismal rectory, the venue for three deaths in thirteen months, his widow gave birth to their son. The boy, baptized six days later at Ockley church, was named Nicholas in honour of the father he would never know.

Sir Edward Culpeper’s patronage apparently expired along with his relation, and Mary was forced to leave the rectory almost immediately. Some time that winter, mother and infant set off along Stane Street, headed for the village of Isfield in Sussex, forty miles away.

The handsome parish church of Isfield is at the confluence of the Rivers Uck and Ouse in Sussex. It sits alone in the middle of a water meadow that floods during wet seasons, bringing water lapping up to the church gate. The small village it serves is nearly a mile away to the south-east, on higher ground. According to local lore (now considered doubtful), it moved there following the Black Death in the fourteenth century, to escape the unhealthy miasma thought to rise from the marshy valley bottom.16 This was the isolated domain of the man who was to be surrogate father to baby Nicholas, his grandfather William Attersoll.

The Revd William Attersoll was, like his recently deceased son-in-law, a Cambridge scholar, having taken his MA at Peterhouse in 1586. Now in his mid-forties, he had served as rector of Isfield since 1600 in a mood of resentment. The living was, by his estimation, ‘poor’. So was the ‘cottage’ that acted as his rectory. A minister of his education deserved better.

The deficiencies of his situation were exacerbated by an ungrateful and ignorant congregation. He was surrounded by ‘enemies to learning’, he claimed, whose judgement was no more valid ‘than the blind man of colours, or the deaf man of sounds’.17

The problem was his theology. Attersoll was a Puritan. The label is a difficult one, covering a multitude of opinions, not all consistent with one another. It was coined in the sixteenth century as a term of abuse (an Elizabethan equivalent of ‘fundamentalist’ or ‘extremist’) to refer to Protestant zealots.18 Those marginalized as Puritan by some were happily accepted as mainstream Protestants by others. They are characterized as hair-shirted ascetics who wanted to ban Christmas and close theatres, yet some of the most theatrical figures of the Elizabethan age – courtiers such as Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, and Sir Walter Raleigh – were associated with the term.

Attersoll’s Puritanism was theologically absolute, and politically conservative. In 1606 he had published his first book, The Badges of Christianity. Or, A treatise of the sacraments fully declared out of the word of God. It was a critical examination of the role of various Christian rites based on a detailed examination of biblical principles. His idea was to purify religious ritual of a residue of Catholic tradition and restore it to the role ordained in the scriptures.

Like most rural communities, the villagers of Isfield were solidly anti-Catholic. However, it was nationalism, not religion, that fed their hatred of ‘papists’. Isfield was just a few miles from the south coast, which had been in a state of alert for over half a century, in constant expectation of a Catholic invasion that might well have happened but for the famous defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. But on matters of religious practice, many wanted to keep the rituals that dated back to the Catholic era. Saints’ days and sacraments were woven into the pattern of their lives. They enjoyed church ales (parish fund-raising events during which potent home brews were sold) and tansy cake. They were reassured by visitations of the sick and ‘churching’, a service for accepting the mother of a newborn back into the congregation after her confinement. Such ceremonies provided them with ‘comfort and consolation’, as Attersoll grudgingly acknowledged. But he believed comfort and consolation could never come from the cosy familiarity of empty pageants. It must come from reading the scriptures, intense self-examination, and devout prayer. He disapproved, for example, of the Catholic ritual of applying ‘extreme unction’, healing holy oil, even though it was still common practice and widely believed to cure illness. No ‘material oil’ could heal them, he protested, only the ‘precious oil of the mercy of God’.19 Illness was even to be welcomed. ‘Sickness of the body is a physic of the soul,’ Attersoll said.20

Life for the villagers was tough enough without having to put up with this, and around 1610 they attempted to oust their austere rector. ‘The calling of a Minister, is a painful and laborious, a needful and troublesome calling,’ Attersoll lamented.21 Nevertheless, he was not prepared to go, and appealed for help to Sir Henry Fanshaw, another scholar and his mentor at Cambridge, who had since become an official in the Royal Court of Exchequer.

The manner of Fanshaw’s intervention is unknown, but it was successful, and Attersoll would continue as rector of the parish for decades to come. Perhaps as a snub to his parishioners, and probably encouraged by the appearance of King James’s Authorized Version of the Bible in 1611, he devoted more time than ever to biblical analysis, producing a number of hefty tomes over the next eight years: The Historie of Balak the King and Balaam the False Prophet (1610), an exposition on the Old Testament Book of Numbers that continued The Pathway to Canaan of 1609; A Commentarie vpon the Epistle of Saint Pavle to Philemon (1612); The Neuu Couenant, or, A treatise of the sacraments (1614); and a massive combined edition of his expositions on Numbers, the Commentarie vpon the Fourth Booke of Moses, in 1618. This was prolixity even by Puritan standards, in the case of the commentary on St Paul’s letter to Philemon, five hundred plus pages arising from just one in the Bible.

He was working on the Commentarie vpon the Fourth Booke of Moses when his daughter Mary appeared at his doorstep, carrying his infant grandchild Nicholas. Attersoll was unlikely to have welcomed the interruption, particularly as he may have been expecting the Culpepers to provide for his widowed daughter. Sir Edward Culpeper had innumerable properties scattered across his Sussex estate, including many close to Attersoll’s parish. Any one of these would have provided a comfortable home for Mary and her fatherless boy. Perhaps such offers had been made, and Mary had declined them in preference for her father. If that was so, the decision was one both he and she would come to regret.

Whatever the circumstances of Mary’s arrival in Isfield, Attersoll had no option but to accommodate mother and child in the cramped rooms of his ‘cottage’ and assume responsibility as Nicholas’s guardian. Being but a ‘poor labourer in the Lord’s vineyard’, the extra cost of having to provide once more for a daughter and now a baby must have a put a strain on Attersoll’s finances, and exacerbated the bile that had built up over his material circumstances.22

There is no mention of Attersoll’s wife at the time Nicholas was in Isfield, suggesting that he was a widower and had been living alone. He had at least one son, also called William, but he was at Cambridge at the time of Mary’s return to the household, preparing dutifully to follow his father into the Church. The university fees and maintenance costs would have added a further strain on the old man’s fixed income.23 This must have made the presence of a child in the midst of Attersoll’s cloistered, scholastic world all the more disruptive.

He certainly did not like children. ‘We see by common experience, that a little child coming into the world, is one of the miser-ablest and silliest creatures that can be devised, the very lively picture of the greatest infirmity that can be imagined, more weak in body, and less able to help himself, or shift for himself, then any of the beasts of the field.’ Looking at an infant, all he could see was the image of men ‘through sin & their revolt from God fallen down into the greatest misery, and lowest degree of all wretchedness’.24

Nevertheless, the care of children was a theme of great concern to him, because it related not only to the children of parents, but also to the children of God. Protestantism was a rebellion against the father-figure of the Pope (whose very title was derived from ‘papa’, the childish word for father). Some Protestants saw this as a liberation, allowing every Christian to find their own way to Christ, carrying the Bible and their sins with them, like Bunyan’s burdened hero in The Pilgrim’s Progress. But it worried Attersoll greatly. He saw ‘godly’ Protestants as being like the Israelites of the Old Testament, escaping the tyranny of the Pope just as the Jews had thrown off the tyranny of the Pharaoh. But the Jews had needed their Moses to guide them to the Promised Land.25 This is what drew Attersoll to the study of Numbers, the fourth book of the Bible, and the penultimate section of the ‘Pentateuch’, the five books said to have been dictated directly to Moses by God. Numbers told the story of the Israelites in the Sinai desert, and Attersoll noted how, as they gathered there, they ‘murmured’ against Moses. Led by Korah, Datham, and Abi’ram, they became idolatrous, conspiring and threatening to destroy, as Attersoll put it, the ‘order and discipline of the Church’ – his intentionally anachronistic term for the religious organization around the Tabernacle, the portable structure used by the Israelites as their place of worship during the Exodus.26 ‘Thus … the wicked multitude usurped ecclesiastical authority,’ Attersoll railed, ‘and endeavoured to subvert the power of the Church-government, and to bring in a parity, that is, an horrible confusion.’ The wicked multitude of his own parish had done the same thing, as had others across the country. All around there were rebellions and usurpations, and there was a social as well as religious need for figures of authority. ‘Magistrates and rulers are needful to be set over the people of God,’ he wrote. They are the ‘father[s] of the country’. Similarly, though ministers of God like himself were no longer called padre, fatherhood was still their role: ‘The Office of the Pastor and Minister of God, is an Office of power and authority under Christ.’27

And here before him was a little child who, like the Protestant children of God, was without a father. It was his responsibility to take on the role.

The model father was, of course, God. In some moods, this meant for Attersoll a New Testament God: embracing, protective, tolerant. Parents should offer their children ‘good encouragement in well doing’, he wrote, as little Nicholas played around his feet. ‘We are bound to praise and commend them, to comfort them, and to cheer them up.’ Of primary importance was education. Uncultivated childish minds ‘bring forth cockle and darnel’, weeds that grow in cornfields, ‘in stead of good corn’. However, many parents ‘do themselves through humane frailty and infirmity sometimes fail in the performance of this duty’, he noted. They ‘cocker’, pamper, their children ‘and are too choice and nice over them, they dare not offend them, or speak a word against them’. This ‘overweening and suffering of them to have their will too much, God punisheth in their children’ by making them rebellious. So, for the ‘right ordering and good government’ of the home, children must be taught, and their first lesson should be in godly discipline. Here, an Old Testament tone emerged. Youth must ‘learn to bear the yoke of obedience’, and it was the responsibility of parents to place it upon their shoulders: ‘If we have been negligent in bringing [children] unto God, and let them run into all riot, and not restrained them, we have cause to lay it to our consciences, and to think with our selves, that we that gave them life, have also been instruments in their death.’28

Nicholas was in some respects a good student of Attersoll’s lessons. As his work in later life would show, he read the classics and scriptures conscientiously, and became mathematically adept. Attersoll also had interesting and unexpected things to say on such matters as astrology and magic. He had an academic, if not practical, knowledge of the stars, noting that they mirrored the hierarchy of heaven and earth in that they ‘are not all of one magnitude, but there is one glory of the Sun, another of the Moon, and another of the Stars for one star differeth from another star in glory’.29

Discipline was more of a problem. The sparse documentation that survives does not provide details, but young Nicholas did not accept the yoke of obedience willingly. ‘The same affection that is between the Father and the Son, ought to be between the Minister & the people committed unto him,’ Attersoll wrote optimistically in 1612.30 Practical experience seemed to suggest a more negative equation. Just like the villagers of Isfield, Nicholas did not feel affection for his surrogate father, and would not do as he was told. Rumours persisted into his adulthood that Attersoll resorted to locking the boy up in his chamber, and leaving him in the dark.31

Lessons had to be learned, and Attersoll was uncompromising. The Bible was held over the boy, and its message battered into his head. God, like kings, expected unconditional obedience. Those set over us are put there by God, and it is his will that we submit to them, Attersoll believed. ‘Evil parents are our parents, and evil Magistrates are Magistrates, and evil Ministers are Ministers’, and, though he dare not write it, evil kings are kings – the position that underlay the belief of England’s monarchs since Henry VIII in their divine right to rule and expectation of unquestioning obedience from their subjects. ‘Servants are commanded to be subject to their masters, not only unto them that are good and gentle, but them that are froward [perverse], so ought children to yield obedience unto their fathers.’32

Underlying this tough message was Attersoll’s belief in predestination. This was one of the central tenets of Protestant theology, and at the time Attersoll was writing accepted by both the established Church and Puritan radicals.33 God, went the argument, must know in advance who will be saved – the ‘elect’, as theologians called them – and who will be damned. If he did not, then it meant he did not have perfect knowledge of the future, which suggested that his divine powers were limited. Attersoll found confirmation of this principle in the Book of Numbers. The book took its name from the census performed by Moses when the Israelites entered the wilderness of Sinai. ‘We learn from hence,’ argued Attersoll, ‘that the Lord knoweth perfectly who [his people] are.’ But his people, being but human and without perfect knowledge, do not know if they are among the elect. The signs were in their behaviour, which showed whether they tended towards godliness or wickedness. For example, rebellious acts, obstructions in the river of godly authority flowing from heaven, were symptoms of a wicked disposition.

In this fateful atmosphere, every act was subjected to providential scrutiny. The most trivial prank could mean the child was doomed, as deadly a sign as a cough indicating consumption. And whichever destiny was signified, salvation or damnation, nothing could be done about it. ‘God keepeth a tally … & none are hidden from him, none escape his knowledge, or sight.’

No absolution could be provided, no repentance sought, no comfort or consolation given. Every time Nicholas broke the ‘bands asunder’ and cast off ‘the cords of duty and discipline’, and the admonishing finger directed him into the dark, it was not the bogeyman who awaited him there, but Satan.34

The daylight world of the scullery was Nicholas’s escape from this predestinarian tyranny. This was where the women were, his adoring mother Mary, wives from the village, the maid. Here, salvation and damnation were replaced by blood and guts. Peeping over counter-tops, crouched in a corner, scurrying alongside blooming skirts, he could watch the preparation of meals and medicines, the skinning of a ‘coney’ (rabbit), its fur being dipped in beaten egg white and applied to heels that were ‘kibed’ or chapped by worn and ill-fitting shoes; cowslips being candied in layers of sugar; tangles of fibrous toadflax being laid in the water bowls to revive ‘drooping’ chickens.35

No fear of religious instruction here. Women were not expected to engage in such pursuits, at least not in Attersoll’s household. He acknowledged that there were ‘many examples of learned women’, his own daughter perhaps among them; but the Bible ‘requireth of them to be in subjection, not to challenge dominion’ of male discourse. The ‘frailness and weakness’ of their sex made them ‘easier to be seduced and deceived, and so fitter to be authors of much mischief’.36 Their place was in the pantry, their role to preserve the frail body, while the male ministry of Attersoll administered to the soul.

Thus, in the company of women, Nicholas encountered the more practical arts of nurturing and healing. Food and physic, chores and hygiene, were inextricably entwined. Here Mary, her awareness sharpened by the tragedy in Ockley, would treat wounds and mix medicines, as well as feed the family and clean the house, using traditional recipes, ingredients and methods handed down the generations, or shared through the village.

The supplies needed to sustain this regime all came through the back door, and it was a young boy’s job to go and fetch them. Outside lay one of the most beautiful and botanically rich areas of the country, a fertile valley on the southern fringes of the Ashdown Forest, the enchanted place into which future generations of children were enticed when A. A. Milne made it the setting for Winnie the Pooh’s Hundred Acre Wood. This landscape became Nicholas’s catechism, the meadows and woods his Sinai desert, the local names of medicinal flowers and shrubs his census of the elect. He attained an intimate botanical knowledge of Sussex, learning, for example, where to find such ingredients as ‘fleur-de-luce’ (elsewhere known as wild pansy, orris, love-in-idleness, and heartsease, the constituent of Puck’s love potion in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and ‘langue-de-boeuf’ (bugloss or borage), noting in later life how their ‘Francified’ names echoed the Norman invasion, which had taken place in 1066 at nearby Hastings.

He heard the women talk of the use of lady‘s mantle to revive sagging breasts, syrup of stinking arrach37 to ward off ‘strangulation of the mother’ (period pains), honeysuckle ointment to soothe skin sunburned by summer days in the fields. They talked of ‘kneeholm’ (‘holm’ is the Old English for holly), ‘dogwood’, ‘greenweed’, and ‘brakes’, the local names for butcher’s-broom, common alder, wold, and bracken. He discovered how every plant had its use, even one as predatory and toxic as brakes. Bracken was, and is, everywhere in Sussex. He would find it erupting in nearby woodland, wherever the undergrowth was disturbed by human activity, harassing stockmen who, during parched summers, would have to drive their animals away from grazing on its fronds, which are suffused with a form of cyanide. Yet the roots, bruised and boiled in mead or honeyed water, could be applied to boys’ itching bottoms to get rid of threadworm. A shovel-load of the burning leaves carried through the house would drive away the gnats and other ‘noisome’ creatures that ‘molest people lying in their beds’ in such ‘fenny’ places as the Sussex lowlands.38

In the graveyard of his grandfather’s church he would pick clary,39 a wild sage, the leaves of which, battered and butter-fried, helped strengthen weak backs. Wandering further up the valley towards the neighbouring village of Barcombe, following the lazy course of the Ouse, negotiating the network of sluices and ditches draining off into the river, he would visit a clump of black alder trees standing next to the brooks and peel back the speckled outer bark to reveal the yellow phloem, or inner bark. Chewed, it turned spittle the colour of saffron; sucked too vigorously, or swallowed, it provoked violent vomiting; but boiled with handfuls of hops and fennel, the grated root of garden succory, or wild endive, and left for a few days, it turned into a bitter, black liquor which, taken every morning, drew down the excess of phlegm and bile that during winter accumulated in the body like the floodwater in the fields outside.

In these fields, he pored over the book of nature in the same fine detail as his grandfather combed the book of God inside. However, when Nicholas was ten, his days of wandering the countryside came to an abrupt end. Attersoll decided the boy needed a more formal education. He was packed off to a Sussex ‘Free School’ ‘at the cost and charges of his mother’ – probably the grammar school in Lewes, six miles away, or perhaps further afield, where he could no longer disturb his grandfather’s work.

Attersoll had also decided upon a vocation for the boy. ‘Every one must know & learn the duties of his own special calling,’ he wrote, and, like Attersoll’s more dutiful son William junior, Nicholas’s was to be the Church. At school, he would learn Latin, a prerequisite for an education in divinity, and a preparation for university.40

Nicholas was sent to Cambridge in 1632, when he was sixteen years old. Little is known about his time there. He may have gone to his father’s college, Queens’, or to his grandfather’s, Peterhouse.41 In any case he would have followed the standard curriculum of the time, covering the seven ‘liberal arts’ – first the core subjects of grammar, logic, and rhetoric, followed by arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy. The way these subjects were taught rested on the authority of the text. Teachers would read out sections from set books, mostly by classical authors, all in Latin, elucidating where necessary. These were gospel. Students were not expected to question or challenge them, only to study and gloss them.

Nicholas’s mother had given him £400 for his ‘diet, schooling, and being at the university’. This was a lot of money, and it is not clear where she got it from – certainly not from the ‘poor labourer’ Attersoll, nor from her late husband’s estate (Nicholas senior’s short career more likely diminished than increased his £120 inheritance). Perhaps it was donated by a benefactor, a Culpeper relative such as Sir Edward’s son William, who had recently inherited his father’s title and estate and would later be described by Nicholas as a godfather figure. Or it may have come from a member of the local gentry to whom Attersoll dedicated his books, such as Sir John Shurley, owner of Isfield Manor.

Wherever it came from, £400 was enough for a comfortable life, leaving a sufficient surplus after board, lodging, and fees for a young student, later famous for his ‘consumption of the purse’, to develop an indulgence, such as smoking tobacco.

Nicholas’s passion for smoking was legendary. Even friends accepted that he took ‘too excessively’ to tobacco. It was the rage in 1630s Cambridge, attracting ‘smoky gallants, who have long time glutted themselves with the fond fopperies and fashions of our neighbour Countries’ and were ‘desirous of novelties’. Smoke-filled student chambers and taverns were an exhilarating change from the stuffy rooms of his grandfather’s cottage, and so were the apothecary shops that acted as the main outlets for tobacco, with their snakeskins and turtleshells in the window, and smells of incense, herbs, and vinegars inside.

Tobacco had been in the country since Elizabethan times. Its introduction to England is attributed to Sir Walter Raleigh, but it was already known before Raleigh’s voyages to America in the 1580s. In 1577, an English translation of an influential herbal by the Spanish physician Nicolas Monardes appeared under the poetic title Ioyfull Nevves out of the Newe Founde Worlde. An entry for ‘the Tabaco, and of his great virtues’ appeared prominently among a variety of exotic discoveries, such as ‘Herbs of the Sun’ (sunflowers), coca, and the ‘Fig Tree from Hell’. Monardes dwelt mostly on tobacco’s medicinal virtues (he claimed it was effective for treating headaches, chest complaints, and the worms), which he had exploited in his own practice in Seville. But he also included a detailed and scintillating report of a religious ritual performed by ‘Indian priests’ in America that had been observed by Spanish explorers. The priest would cast dried tobacco leaves upon a fire and ‘receive the smoke of them at his mouth, and at his nose with a cane, and in taking of it [fall] down upon the ground, as a dead man’. ‘In like sort,’ Monardes added, ‘the rest of the Indians for their pastime do take the smoke of the Tabaco, for to make themselves drunk withal, and to see the visions, and things that do represent to them, wherein they do delight … And as the Devil is a deceiver, and hath the knowledge of the virtue of herbs, he did shew them the virtue of this herb, that by the means thereof, they might see their imaginations, and visions, that he hath represented to them, and by that means doth deceive them.’ For this reason, Monardes placed the herb among a class of herbs ‘which have the virtue in dreaming of things’, hallucinogenics such as the root of ‘solarto’ (Belladonna or Deadly Nightshade), which, taken in wine, ‘is very strange and furious … and doth make him that taketh it dream of things variable’. Such properties encouraged English merchants with Spanish contacts to source samples of the herb for an eager market back home. The translator of Ioyfull Nevves, John Frampton, noted in the book’s dedication to the poet and diplomat Edward Dyer how the ‘medicines’ Monardes mentioned ‘are now by merchants and others brought out of the West Indies into Spain, and from Spain hither into England, by such as do daily traffic thither’.42

The tobacco plant featured in Nicolas Morandes’s herbal.

England, however, was at war with Spain during the latter years of the sixteenth century, and tobacco remained a rarity. That all changed in the 1620s, when bountiful supplies of a sweet, pungent variety, superior even by Spanish standards, began to be cultivated in England’s newly-established colony of Virginia in North America, fuelling a surge in consumption.

The sudden spread of such a potent herb among the young alarmed the authorities. In the House of Commons, knights of the shires demanded that it be banned ‘for the spoiling of the Subjects’ Manners’. In his Directions for Health, first published in 1600 and one of the most popular medical books of the time, William Vaughan warned against the ‘pleasing ease and sensible deliverance’ experienced by young smokers, and, targeting his health-warning at the area that was likely to cause them greatest concern, urged them ‘to take heed how they waste the oil of their vital lamps’. ‘Repeat over these plain rhymes,’ he instructed:

Tobacco, that outlandish weed,

It spends the brain, and spoils the seed:

It dulls the sprite, it dims the fight,

It robs a woman of her right.43

The sternest critic was King James himself. In 1604, he published his Counterblaste to Tobacco, in which he condemned the ‘manifold abuses of this vile custom of tobacco taking’. ‘With the report of a great discovery for a Conquest,’ he wrote, recalling Sir Walter Raleigh’s voyages to colonize Virginia, ‘some two or three Savage men were brought in together with this Savage custom. But the pity is, the poor wild barbarous men died, but that vile barbarous custom is yet alive, yea in fresh vigour.’

The King was particularly affronted by the medicinal powers claimed for the plant. It had been advertised as a cure for the pox, for example, but for James ‘it serves for that use but among the pocky Indian slaves’. He examined in detail its toxic effects, displaying an impressive grasp of prevailing medical theories. Following the intellectual fashion of the time, he also drew an important metaphorical conclusion about his own role in dealing with such issues: he was ‘the proper Physician of his Politic-body’ whose job was ‘to purge it of all those diseases by Medicines meet for the same’.

But even the efforts of an absolute monarch could not stop the spread of this pernicious habit. ‘Oh, the omnipotent power of tobacco!’ he fumed, consigning it to the same class of intractabilities as religious extremism: ‘If it could by the smoke thereof chase out devils … it would serve for a precious relic, both for the superstitious priests and the insolent Puritans, to call out devils withal.’44

His ravings had no effect on consumption. Imports of tobacco boomed: 2,300 pounds in 1615, 20,000 in 1619, 40,000 in 1620, 55,000 in 1621, two million pounds a year by 1640.45 The more popular it became, the more James found that even he could not do without it. ‘It is not unknown what dislike We have ever had of the use of Tobacco, as tending to a general and new corruption, both of men’s bodies and manners,’ the King announced in a proclamation of 1619; nevertheless, he considered ‘it is … more tolerable, that the same should be imported amongst many other vanities and superfluities’ because, without it, ‘it doth manifestly tend to the diminution of our Customs’.46 In other words, the health risks of smoking were less important than his need for money.

James’s fiscal needs were certainly pressing. Since the reign of Elizabeth, finance had been a source of growing tension between the monarchy, Parliament, and members of the upper and ‘middling’ classes of society rich enough to pay taxes. Under England’s often anomalous constitutional arrangements, the King, though an absolute monarch, had to summon a Parliament – representing the nobility and the bishops in the House of Lords, mostly the landowning, professional, and merchant classes in the Commons – if he wanted to raise taxes. James had several sources of private revenue, such as rents and fines, but their value had eroded during a period of escalating inflation.47 Thus he was forced on several occasions to summon Parliament and haggle over his income, a process that tended to force some of the extravagances and corruptions of his court humiliatingly into the light. His response was to look for more private ways of raising money that did not require parliamentary consent. He borrowed heavily from the City of London, a ready source of money but provided, as events later showed, with strings. He started selling titles. He invented the lower rank of ‘baronet’, aimed at members of the gentry such as Sir Edward Culpeper, which offered the prestige of nobility without the prerogatives. He exploited feudal privileges such as ‘wardships’, a royal right to the income from estates inherited by under-age heirs. However, his most lucrative source of revenue was customs duties. These were notionally under the control of Parliament but, following a convention established in the reign of Edward IV, were granted to James for the duration of his reign. Taking advantage of the concession, he supplemented the income they generated with special duties or ‘impositions’ levied on particular goods. A test case brought in 1606 by a merchant who refused to pay the imposition on a hundredweight of currants affirmed that James was entitled to the money, on the grounds that the royal prerogative was ‘absolute’. The custom duty due on tobacco was 2d. per pound weight in 1604. James initially increased it more than fortyfold by adding an impost of 6s. 10d. a pound, a rate so punitive it proved unenforceable and had to be reduced. Exploiting another controversial privilege, he then granted a patent for control of the entire tobacco trade to a court favourite, who in return for the right to ‘farm’ the duties was expected to pay up to £15,000 a year into the royal exchequer. Later still, he allowed for the practice of ‘garbling’, imposing an obligation on merchants to have their goods checked and sealed by an official. It was claimed such a measure was needed to prevent the sale of bad or adulterated tobacco, but in practice it was used to increase revenue, as the officials began to charge a further 4d. per pound for passing each bale of tobacco. Such prescriptions set the tone not only of James’s fiscal policy, but also that of his heir, Charles I – a purgative applied by these physicians of the ‘Politic-body’ that would result in the most dreadful convulsions.

As well as being embroiled in such political controversies, tobacco was associated with intellectual ones as well. Critics disapprovingly noted that the herb carried the endorsement of philosophers such as Giambattista della Porta. Della Porta’s Natural Magick (first published in Latin in 1558 as Magiae naturalis) was one of a series of notorious sixteenth-century works that contained combustible mixes of herbalism, medicine, religion, magic, alchemy, and astrology. Such works had inspired a flowering of interest in magic in England, and particularly at Cambridge University, encouraged by Queen Elizabeth’s magus Dr John Dee (who had noted the properties of tobacco in his copy of Monardes’ herbal) and reflected in works such as Spenser’s Faerie Queene and Shakespeare’s The Tempest. In later years, tobacco also became associated with religious fanaticism. A sect called the Ranters thought that, since predestination meant that your fate in the next life was fixed, you may as well make the most of this one, and so smoking (along with drinking, feasting, and whoring) became elevated to a sacrament. Even the more sober Baptists were partial to a smoke during their services.48

Thus, a pipe of tobacco in the early seventeenth century took the smoker on a heady botanical, political, and philosophical, as well as recreational, trip. This made it all the more appealing to a young Cambridge undergraduate with a curious mind and a full pocket. It was also the reason why the university authorities tried to ban smoking. They failed, or even had the reverse effect, and Nicholas was one among many who enjoyed flouting the prohibition.

Anticipating future generations of students, Nicholas may even have grown his own. He was certainly well acquainted in later life with ‘yellow henbane’, a variety of tobacco that he thought originated in Brazil and was now widespread in England. He knew what it looked like, and where it grew. He described the saffron juice derived from the leaves as an effective expectorant for ‘tough phlegm’. He also later noted in one of his medical books that the bruised leaves ‘applied to the place aggrieved by the king’s evil’ would alleviate discomfort. ‘Indeed,’ he added, ‘a man might fill a whole volume with the virtues of it.’49 Given the context, this must surely have been a mischievous reference to royal disapproval of the domestic weed.50 In 1619, James, under pressure from the settlers in Virginia and enticed by the prospect of greater revenues, issued a proclamation banning the cultivation of tobacco in England (which, being domestically grown, was free of excise duties and impositions). His grounds were that the ‘Inland plantation’ had allowed tobacco to ‘become promiscuous, and begun to be taken in every mean Village even amongst the basest people’, and because ‘divers persons of skill and experience’ had told him that the English variety was ‘more crude, poisonous and dangerous’ than the Virginian. The same disapproving policy continued into the reign of Charles I, who took further measures to monopolize its importation and to license its sale, on the grounds that it was ‘taken for wantonness and excess’.51

Nicholas evidently saw smoking as a badge of the anti-authoritarianism that was to define his career, and it seems the two were combined into an intoxicating mix in his Cambridge days. However, it was another act of rebellion that was to have the most decisive influence on his forthcoming career.

The story is related in the most melodramatic style in a short, anonymous memoir concerning Nicholas that appeared in the introduction to a posthumous edition of one of his works:

One of the first Diversions that he had amongst some other smaller transactions and changes, none of his Life proving more unfortunate, was that he had engaged himself in the Love of a Beautiful Lady; I shall not name her for some reasons; her Father was reported to be one of the noblest and wealthiest in Sussex.52

The identity of the lady remains a mystery. She had a personal estate worth £2,000 and a private income of £500 a year, according to the memoir, figures consistent with the wealth of, say, the daughter of a rich baronet, such as Sir John Shurley (1569–1631). Sir John was the owner of the manor of Isfield, and had an extended family that included a few possible candidates.53 If the lady belonged to the Shurley clan, it is easy to see why Nicholas kept the love affair secret. Sir John was William Attersoll’s patron. Attersoll dedicated two of his books to Sir John, and became a beneficiary of the baronet’s will in 1631 – the time that the adolescent intensities of Nicholas’s illicit love affair presumably came into flower in the woodlands around Isfield, and just before they were interrupted by his departure for Cambridge.

Nicholas was no match for a rich member of one of the most ancient and respected families in the county. He may have been a Culpeper, but he was from an inferior branch. The very suggestion of such a relationship would have caused his grandfather great embarrassment. ‘Parents have often too severe eyes over their Children’, as the memoir observed, and Nicholas knew only too well that Attersoll would bring down the wrath of an Old Testament God upon such a union. So the couple decided upon their ‘Martyrdoms’ – an elopement. ‘By letters and otherwise’ they plotted to meet in Lewes, where they were to be married in secret ‘and afterwards for a season … live privately till the incensed parents were pacified’.

On the appointed day, probably some time in 1633 or early 1634, the lady and one of her maids hid among their skirts ‘such Rich Jewels and other necessaries as might best appertain to a Journey’, while Nicholas pocketed the £200 left over from the money his mother had given him for his education at Cambridge. The Romeo set off by coach, the Juliet by foot, to rendezvous at the chapel in Lewes, where a priest waited to perform their secret nuptials.

As he approached his destination, news reached Nicholas of a providential intervention. As his bride-to-be and her companion were making their way across the Downs they were ‘suddenly surprised with a dreadful storm, with fearful claps of Thunder surrounded with flames of Fire and flashes of Lightning, with some of which Mr Culpeper’s fair Mistress was so stricken, that she immediately fell down dead’. A family friend passed by Nicholas’s coach as he received the news and took the distraught young man to the rectory at Isfield. The unexpected appearance of her son filled Nicholas’s mother with joy, until she became aware of the circumstances that had brought him there. The shock, according to the memoir, struck her down with an illness from which she would never recover.54

Nicholas’s relationship with Attersoll was also terminally injured. It was yet more evidence of the young man’s irredeemable rebelliousness. ‘If we have warned them, and they would not be warned,’ Attersoll thundered in one of his biblical commentaries, ‘if we taught and trained them up in the fear of God, which is the beginning of wisdom, and they have broken the bands asunder, and cast the cords of duty and discipline from them, we may comfort our selves as the Minister doth, when he seeth his labour is spent in vain.’55 Attersoll disinherited his ward, and gave up on his religious education.

Nicholas left Cambridge in a state of ‘deep melancholy’. He could not stay in Sussex either; so, like many others who find themselves in need of a fresh start and a new life, he set off for that refuge of the dispossessed: London, where for a while he disappears from the historical record and our story, as others take centre stage.

* This and the following extracts introducing each chapter are taken from Culpeper’s The English Physitian.