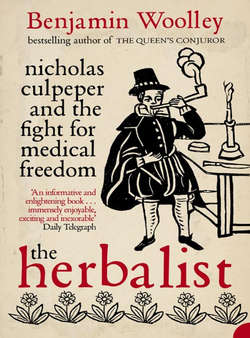

Читать книгу The Herbalist: Nicholas Culpeper and the Fight for Medical Freedom - Benjamin Woolley - Страница 7

BORAGE Borago officinalis

ОглавлениеThese are very Cordial. The Leaves or Roots are to very good purpose used in putrid and Pestilential Fevers, to defend the Heart, and help to resist and expel the Poison, or the Venom of other Creatures.

The Flowers candied, or made into a Conserve are … good for those that are weak with long sickness, and to consumptions, or troubled with often swoonings or passions of the Heart: The Distilled Water is no less effectual to all the purposes aforesaid, and helpeth the redness and inflamations of the Eyes being washed therewith: The dried Herb is never used, but the green; yet the Ashes therof boiled in Mead, or Honeyed Water is available against Inflammations and Ulcers in the Mouth or Throat, to wash and gargle it therewith. The Roots are effectual being made into a licking Electuary, for the Cough, and to condensate thin phlegm, and Rheumatic Distillations upon the Lungs.

The Seed is of the like effect; and the Seed and Leaves are good to encrease Milk in Women’s Breasts: The Leaves, Flowers and Seed, all, or any of them are good to expel Pensiveness and Melancholy. It helpeth to clarify the Blood, and mitigate heat in Fevers. The Juice made into a Syrup prevaileth much to all the purposes aforesaid, and is put with other cooling, opening, cleansing Herbs, to open obstructions, and help the yellow-Jaundice, and mixed with Fumitory, to cool, cleans, and temper the Blood, thereby it helpeth the Itch, Ringworms, and Tetters, or other spreading Scabs or Sores.

They are both Herbs of Jupiter, and under Leo, both great Cordials, great strengtheners of Nature.

Borage is covered with a soft down, and has round, ‘succulent’ stems about 1½ feet tall. The leaves are large, wrinkled, and deep green. It produces a froth of brilliant blue flowers. The fresh herb tastes of cucumber and is cooling, hence the association with staying the passions of the heart. Mixed with lemon and sugar in wine, it makes a refreshing summer drink which, according to the Victorian naturalist Richard Jefferies, used to be doled out to thirsty travellers at London railway stations.1 ‘A modern conceit,’ writes Richard Mabey, ‘is to freeze the blue flowers in ice-cubes.’2 The leaves mixed in salad are also said to fend off despondency.

In many herbals, Bugloss was considered to be the same plant, though Culpeper recognized them as different herbs with similar medicinal effects.

According to some authorities, the name is a corruption of corago, from the Latin cor, the heart, and ago, I bring.

In 1512, soon after the succession of Henry VIII, an act was passed by Parliament complaining about the ‘Science and Cunning of Physic and Surgery (to the perfect knowledge whereof be requisite both great Learning and ripe Experience)’ being ‘exercised by a great multitude of ignorant persons, of whom the greater part have no manner of insight in the same, nor in any other kind of learning’. Some of these ignorant persons were illiterate, others no better than ‘common Artificers, as Smiths, Weavers, and Women’ who ‘boldly and accustomably take upon them great Cures, and things of great Difficulty; in the which they partly use Sorcery and Witchcraft, partly apply such Medicines unto the disease as be very no[x]ious, and nothing meet therefore, to the high displeasure of God, great infamy to the Faculty, and the grievous Hurt, Damage, and Destruction of many of the King’s liege People, most especially of them that cannot discern the cunning from the uncunning’. The act therefore ruled that anyone wanting to practise medicine or ‘physic’ within seven miles of London must first submit themselves to examination by the Bishop of London or Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral, ‘calling to him or them [bishop and dean] four doctors of physic … as they thought convenient’.3 The religious authorities were to police the system because it was still widely accepted that the Church was primarily responsible for personal welfare, body as well as soul.

However, in September 1518, Henry VIII himself intervened by issuing a Charter that took the power to regulate medicine in London out of the hands of the Church and gave it to a new body, the ‘College of Physicians’. This would issue licences to those considered learned and skilled enough to practise, and impose fines of up to £5 per month upon those who practised without a licence. The College was to be financed by these fines, as well as fees for conducting examinations and issuing licences.

In London at the time, nearly all forms of commercial activity were controlled by guilds. These organizations were responsible for the apprenticeship system that trained new entrants into each trade, trainees being ‘bound’ to a master for a period typically of seven or eight years during which they would learn their craft. Once they had reached a sufficient standard of skill, they were ‘freed’ to practise in their own right. As freemen, they acquired a high degree of political influence, at least by the standards of the time. They could vote in elections for the Common Council, the City’s parliament, and through their guilds controlled the City’s administration: the Court of Aldermen and the Lord Mayor.

The guilds were concerned with social as well as political status, and were preoccupied with matters of rank and dress. Each had its own uniform and liked to parade their colours on special occasions, which was why the guilds came to be known as livery companies. They fought ferociously over matters of precedence, jockeying for position in the official list of the twelve ‘chief companies, from whose membership the Lord Mayor was chosen annually. The most powerful was the Company of Mercers (cloth merchants), followed by the Grocers (originally known as the ‘Pepperers’), the Drapers, the Fishmongers, the Goldsmiths, the Skinners, and so on.

The College of Physicians did not fit comfortably into this delicately arranged system. It was small – its membership was capped at twenty to thirty members or ‘Fellows’ compared to a thousand or so in the larger livery companies – yet its influence was enormous as it served not only most members of the Privy Council but the royal household itself, a fifth of the Fellows being officially engaged in attending the monarch. It exercised a monopoly over practice, and set standards, yet had no responsibility for training. In 1525, in an attempt to regularize the position, the Common Council passed an act accepting the College’s monopoly of medical practice but banned Fellows from dispensing medicines. This was to protect the Grocers, among whose ranks were the apothecaries, specialists in medicinal supplies and the preparation of prescriptions.4

These arrangements laid the foundations for a medical system overrun with anomalies and riven with rivalries. It was a mess that got messier with every successive attempt to rationalize it. In the 1540s, an act was passed ‘for the enlarging of their [the College’s] privileges, with the addition of many new ones’, as the College’s first official history put it. Among the privileges so enlarged was the control the College exercised over the apothecaries. Henceforth, its officials were to have ‘full authority and power, as often as they shall think meet and convenient, to enter into the house or houses of all and every Apothecary … to search, view and see such Apothecary wares, drugs and stuffs as the Apothecaries or any of them have’. Any stuffs found ‘defective, corrupted and not meet nor convenient’ the doctors could order to be immediately destroyed on the offender’s doorstep.5

The same year, another act amalgamated the Company of Barbers and the Guild of Surgeons, perversely in order to separate the two crafts. Surgery – or ‘chirurgery’, as it was then known, derived from the Greek for handiwork – was a manual occupation, learned like any other craft through apprenticeship. Its role in healing was to deal with external operations: amputating limbs, cauterizing wounds, resetting dislocations, removing tumours, letting blood, extracting teeth, and – the area that produced the most common demarcation disputes with the physicians – treating skin conditions, including diseases such as plague and pox. Since many members of the Barbers’ Company also offered such services, the aim of bringing them together with the surgeons was to ensure that they did so according to common standards. Surgeons who ‘oftentimes meddle and take into their cure and houses such sick and diseased persons as [have] been infected with the Pestilence, great Pox, and such other contagious infirmities’ were forbidden to ‘use or exercise Barbery, as washing or shaving, and other feats thereunto belonging’, and barbers were likewise forbidden from performing ‘any Surgery, letting of blood, or any other thing belonging to Surgery (drawing of teeth only excepted)’. To encourage the development of surgical skills, the act pledged an annual entitlement of four fresh corpses from the gallows, for use in anatomical lectures.6

Having established surgery as a separate craft, another act was passed in 1543, just two years later, which threatened to destroy it. Dubbed the ‘Quacks’ Charter’, its preamble launched a blistering attack on the surgeons for their ‘small cunning’. ‘They will take great sums of money and do little therefore, and by reason thereof they do oftentimes impair and hurt their patients,’ it objected. Because of this, the act ruled that ‘every person being the King’s subject, having knowledge and experience of the nature of herbs, roots and waters or of the operation of the same’ should be allowed ‘to practise, use and minister in and to any outward sore, uncome [attack of disease], wound, apostemations [abcess], outward swelling or disease, any herb or herbs, ointment, baths, poultices and plasters, according to their cunning, experience and knowledge’.7 This effectively allowed more or less anyone to perform any surgical operation that did not require a scalpel.

The identity of those who initiated the Quacks’ Charter is unclear, but the physicians must be among the suspects. They were concerned that the Barber Surgeons Act had given the surgeons too much power and were eager to undermine their privileges. The act may also have been a response to Henry VIII’s religious reforms. In the late 1530s, the process had begun of closing the Catholic monasteries, which until then had run the hospitals. This created a crisis in public healthcare that the act could help alleviate. Whatever prompted it, the effect was chaos, as it did not specify who was to determine the ‘knowledge and experience’ of those that it allowed to practise.

The College lobbied both monarch and Parliament for further acts and charters reinforcing its own position. It also produced its own ‘statutes’, setting out in meticulous detail its rules and procedures. The earliest that survive date from 1555. They were written by Dr John Caius, one of the College’s most influential sixteenth-century presidents. His name was originally ‘Keys’, but, following a practice popular among intellectuals wanting to add gravitas to their names, he Latinized it to ‘Caius’, but kept the original pronunciation.

Dr Caius’ statutes specified that there should be quarterly meetings, ‘Comitia’, attended by all the Fellows. At the Michaelmas Comitia (held on 30 September), the College selected from among its number a president and eight seniors or ‘Elects’. The Elects would then choose the ‘censores literarum, morum et medicinarum’, censors of letters, morality, and medicine – effectively the custodians of the physicians’ monopoly. They were to exercise these roles, not with the ‘rod of iron’ of olden times, Caius declared, but with a caduceus, the mythical wand entwined with two serpents carried by the Greek god Hermes, representing gentleness, clemency, and prudence, which has since become a symbol of medical practice. Caius personally donated a silver caduceus to remind the Censors of this responsibility. It was one they would often forget.8

Their first role as censors of ‘letters’, or medical literature, was aspirational. They may have wanted to control the licensing of medical books, but this responsibility belonged to another livery company, the Stationers’, working under the supervision of the Church. As censors of morals they were primarily concerned with enhancing the physicians’ professional image. The Fellows were touchy about their social status. Since antiquity, physicians had aroused mixed feelings in society. ‘The physician is more dangerous than the disease,’ went the proverb.9 In the prologue of the Canterbury Tales, Chaucer introduced a ‘Doctor of Physic’ as a figure of learning, knowledgeable in ‘magic natural’ and well read in the medical classics, but ‘His study was but little on the Bible’. This was a reference to the old saying ubi tres medici, duo athei: ‘where there are three physicians, there are two atheists’, the suspicion of atheism arising from their devotion to classical (i.e. pagan) knowledge. The slur rankled – the ‘general scandal of my profession’, the physician, essayist, and Honorary Fellow of the College Sir Thomas Browne called it in his masterwork Religio Medici (1642). Chaucer had also alluded to another accusation, that doctors were greedy, making money out of the misery of others by prescribing expensive medicines and charging exorbitant fees: ‘For gold in physic is a cordial;/Therefore he loved gold in special’.10 The sentiment was echoed by Christopher Marlowe in his play Dr Faustus (published 1604), when the eponymous hero contemplates his prospects:

Bid Economy farewell, and Galen come:

Be a physician, Faustus; heap up gold.11

But, as every physician knew, in a medical emergency, attitudes were different. When a child sickens, when boils erupt, when fever grips, when plague knocks on the door, then the physician is ‘God’s second’, as the playwright and satirist Thomas Dekker put it, lampooning the public response to plague. ‘Love thy physician,’ he advised, adding that ‘a good physician comes to thee in the shape of an Angel’, unable to resist the common play on a word that then referred both to a divine messenger and a gold coin.12

The Censors’ moral role was aimed at counteracting this image by imposing a strict code of conduct. This code was not concerned with issues such as behaviour towards patients, the level of fees, or charitable obligations. It was about insisting that Fellows dressed in scarlet and silk caps on public occasions and addressed the College President always as ‘your excellency’. It was about prohibiting College members from accusing one another of ignorance or malpractice, intervening in a colleague’s case unless invited, questioning a colleague’s diagnosis, employing apothecaries who practised medicine, or disclosing the recipes of medicines.13

The College’s Annals show that most Fellows observed these ‘moral’ strictures to the letter. When it came to internal discipline, the only matter the President and Censors had to concern themselves with on a regular basis was absenteeism, which was rife. The primary concern was external discipline, the policing not of colleagues, but competitors.

As censors of medicine, the College was entitled to control the practice of medicine in London or within a seven-mile radius of its walls. Anyone reported to be practising without a licence faced a summons from the College beadle and the threat of a fine or imprisonment. And what an apparently motley bunch the beadle brought in, with names, as the medical historian Margaret Pelling has noted, worthy of a Jacobean comedy: Gyle, Welmet, Wisdom, Blackcoller, Lumkin, Doleberry, Sleep, Buggs, Hogfish, Mrs Pock, Mrs Paine and Mother Cat Flap.14 Those who voluntarily presented themselves to the Censors, seeking a licence, tended to appear under more respectable names, usually Latinized, like that of the College luminary Dr Caius: Angelinus, Balsamus, Fluctibus. They had to prove to the Censors that they had a firm grasp of medical theory. To establish whether or not this was the case, they were examined, not on their knowledge of the latest anatomical theories or diagnostic techniques, the revolutionary findings of the great Renaissance medics and anatomists such as Jean Fernel of Paris or Gabriele Falloppia of Padua, but on their understanding of the works of a physician and philosopher who had lived a millennium and a half earlier.

No other field of knowledge has been dominated by a single thinker as medicine was by Galen. Born in AD 129 in Pergamon (modern Turkey) to wealthy parents, Galen was, in many respects, a model physician: studious, clever, and arrogant. In his youth, he studied at the Library of Alexandria, the great repository of classical knowledge, and travelled to India and Africa, learning about the drugs used there. He became a skilful anatomist who could expertly cut up an animal living or dead, and, though the dissection of humans was taboo, he had attained a grasp of human physiology thanks to a spell as physician to the gladiators. He also had an astute understanding of patient psychology and was very good at attracting prestigious clients, including the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, an endorsement he never lost an opportunity to advertise.

As well as being a brilliant practitioner, Galen gave medicine academic respectability. Basing his ideas on those of Hippocrates, the semi-mythical Greek physician immortalized as the author of the Hippocratic Oath, he created a comprehensive theoretical system that seemed to provide a sound basis for understanding and treating disease. Underlying this system was a view of the body as a system of fluids in a state of constant flux. There were four such fluids or ‘humours’: blood, phlegm, choler (yellow bile), and melancholy (black bile). The relative proportions of these humours in different parts of the body determined its temperament, and an imbalance produced illness. A runny nose was a result of excess phlegm, diarrhoea of choler, a nosebleed or menstruation of blood, particles of black material in vomit or stools of melancholy (the most elusive of the humours). The identification of these four humours provided a convenient way of tying the workings of the body in with the prevailing view of how the universe worked. Everything in the cosmos was understood to have a character defined by its place in a quadrilateral scheme: the four seasons, the four ages of man (infancy, youth, middle age, old age), the four points of the compass, the four ‘elements’ that make up all matter (fire, air, water, and earth), the four ‘qualities’ that determine their character (hot, dry, moist, cold). Each humour had its place in this scheme: phlegm was cold and moist, combining the character of winter, frozen by northerly winds, and the wet weather of the westerlies that blew in spring, which explained why so many people suffered runny noses during those seasons; choler was hot and dry, excessive during summer and autumn, the seasons of stomach disorders, when it would flow most copiously.

The treatment of disease involved trying to rebalance the humours, achieved through diet or eliminating the surplus humour. A fever, for example, might be caused by an excess of blood in a particular part of the body, which, unable to escape, putrefies, producing heat (just as organic material in a compost heap becomes warm as it rots). The solution, therefore, was to drain off the superfluity by such methods as blood-letting or, in the case of other humours, prescribing ‘purgatives’, medicines that provoke the evacuation of bile through vomiting or diarrhoea, or herbs that produce a runny nose.

Galen’s understanding of disease was supplemented by an equally systematic understanding of the body, derived from his own dissection and vivisection experiments, as well as prevailing philosophical ideas. He saw the body as a system for extracting from the environment the life force or pneuma, an ‘airy substance, very subtle and quick’, and modifying it into three spirits or ‘virtues’: vital, which vivified the body; natural, which fed it; and animal, which produced sensation and movement. According to this view, ‘chyle’, a milky substance derived from the digestion of food in the intestine, is carried to the liver via the portal vein, where it is manufactured into blood imbued with natural spirit. This dark nutritive blood passes through the veins into the body, where it is consumed, feeding the muscles and creating tissue. Some of this blood also reaches the right chamber or ‘ventricle’ of the heart, from where it either passes into the lungs, which filter and cool it, or seeps into the left ventricle via invisible pores in the septum, the membrane separating the heart’s two chambers. Thus the heart ‘snatches and, as it were, drinks up the inflowing material, receiving it rapidly in the hollows of its chambers. For [think if you will] of a smith’s bellows drawing in the air when they are expanded [and you will find] that this action is above all characteristic of the heart; or if you think of the flame of a lamp drawing up the oil, then the heart does not lack this facility either, being, as it is, the source of the innate heat, or if you think of the Herculean stone [a loadstone or magnet] attracting iron by the affinity of its quality, then what would have a stronger affinity for the heart than air for its refrigeration? Or what would be more useful than blood to nourish it?’15 Like nutritive blood in the veins, the bright red blood vitalized by the heart ebbs and flows through the pulsing arteries, like tidal water through rivers and streams, irrigating the body. The brain produces the animal virtue, which is distributed through the body via the nerves, producing feeling and movement. In addition to these three virtues, the male body also produces procreative spirit in the testicles that is distributed as sperm through the ‘spermatic vessels’ to the woman’s womb (whether the ovaries produced procreative material in a similar manner was to remain a matter of controversy for centuries to come).16

Galen was very pleased with this theory, and considered it definitive. ‘I have done as much for medicine as Trajan did for the Roman Empire, when he built bridges and roads through Italy,’ he wrote. ‘It is I, and I alone, who have revealed the true path of medicine. It must be admitted that Hippocrates already staked out this path … he prepared the way, but I have made it passable.’17

Galen underestimated his influence. His ideas survived not only Trajan’s Rome, but the sacking of the great Library of Alexandria, the birth and spread of Christianity and Islam, the Black Death, the invention of printing, and the Reformation – a millennium and a half of history – with barely any adjustment. As late as 1665, one medical reformer was complaining that ‘an Extreme Affection to Antiquity [has] kept Physic, till of late years as well as other Sciences, low, at a stay and very heartless, without any notable Growth or Advancement’. Galenism held sway over the College of Physicians from the day it was founded. Everyone who wanted to practise medicine in London had to conform to its principles. This was still the case on 4 May 1603 when the twenty-five-year-old William Harvey presented himself to the Censors of the College of Physicians to apply for a licence to practise.18

Little did the Censors appreciate what the young man who sat before them would do for their profession. William Harvey went on to become a colossus of the medical world, hailed as one of the world’s greatest anatomists and England’s first true scientist. Sir Geoffrey Keynes, author of the definitive 1967 biography of Harvey, was so overcome with admiration for his subject, he concluded that ‘even if we wished to do so, it would be difficult, from the evidence in our possession, to find any serious flaw in Harvey’s character’. One contemporary wrote that his ‘Sharpness of Wit and brightness of mind, as a light darted from Heaven, has illuminated the whole learned world’.19

Harvey was born on 1 April 1578 to Joan, ‘a Godly harmless Woman … a careful tender-hearted Mother’, and Thomas Harvey, mayor of Folkestone in Kent, a rich landowner with properties not far from Isfield.20 After attending King’s School in Canterbury, he was sent to Gonville and Caius College Cambridge, where its benefactor Dr Caius was Master. Caius had made medicine a core part of his college’s curriculum, securing a royal charter allowing two bodies of criminals executed in Cambridge to be used for anatomical demonstrations. Harvey’s own education benefited from this arrangement as he later recalled seeing ‘a frightened person hanged on a ladder’ at Cambridge, and presumably witnessed the subsequent dissection.21 The variety of medicine taught was, of course, devoutly Galenic. Caius had studied at Padua with Andreas Vesalius, the father of modern anatomy, whose discoveries based on human dissections had challenged many of Galen’s, which had relied upon animals. Despite this, when Vesalius later suggested to Caius that an obsolete passage should be dropped from a collection of Galen’s writings Caius was editing, Caius refused on the grounds it would be too dangerous to tamper with such an ancient work.

In 1600, Harvey himself went to Padua and studied anatomy under one of Vesalius’ successors, Hieronymus Fabricius. Fabricius had designed the first modern anatomy theatre, a wooden structure set up in the university’s precincts, which featured a stone pit surrounded by five concentric oval terraces. Harvey gazed from those terraces and into that blood-spattered pit on many anatomical, and in particular venereal, marvels that he would later memorably recall in his lectures, including syphilitic ulcers that had gnawed into the stomach of a prostitute, a boy whose genitals had been bitten off by a dog, and a man without a penis who was apparently still capable of sex.22

Harvey may also have witnessed Fabricius’ work on one small but important area of anatomical controversy: valves in the veins. These were shown by dissection to block the passage of blood through the veins into parts of the body such as the legs. Though working in the shadow of Vesalius, Fabricius was a Galenist such as Caius would have been proud of and was concerned that the valves conflicted with Galen’s view that the veins carried blood from the liver into the body. His ingenious solution was to argue that the valves were there to act like sluice gates, preventing the legs becoming engorged with blood, and ensuring an even distribution of nutritive spirit to other parts.

Harvey received his Doctorate in Medicine (MD) in Padua after just two years and was back in London by 1603, living in a modest house near Ludgate, under the shadow of St Paul’s Cathedral. Eager to start work, he approached the College of Physicians, perhaps with an introduction from Caius, seeking the all-important licence he needed to practise. He arrived at the College for his first examination at a nervous time. The previous week, Queen Elizabeth had been buried at Westminster Abbey after forty-four years on the throne. Her legacy to her Scottish cousin and successor James was not the settled stability of patriotic memory but seismic tensions produced by her refusal in her final years to deal with pressing issues of political and religious reform. London also faced the onset of plague, one of the worst epidemics for a generation. ‘He that durst … have been so valiant, as to have walked through the still and melancholy streets, what think you should have been his music?’ wrote Thomas Dekker in his review of the year. ‘Surely the loud groans of raving sick men, the struggling pangs of souls departing, in every house grief striking up an alarum, servants crying out for masters, wives for husbands, parents for children, children for mothers; here he should have met some frantically running to knock up Sextons; there, others fearfully sweating with coffins, to steal forth bodies, least the fatal handwriting of death should seal up their doors.’23 It was through such streets that Harvey walked as he made his way to the small stone house in Knightrider Street then occupied by the College.

Harvey’s credentials assured him a sympathetic reception. For his first examination he faced an interview board of four rather than the usual five Fellows, the absentee presumably being one of the many physicians who had fled the capital during the epidemic. The young man the assembled doctors beheld was short, with raven-black hair and small dark eyes ‘full of spirit’. He was, as a contemporary put it, ‘choleric’, referring to the Galenic tradition that associated an individual’s character with his or her ‘complexion’, the natural balance of their humours – choleric, melancholic, sanguine, phlegmatic. Choleric people had an excess of choler, which made them, as Nicholas Culpeper later put it in his guide to Galen’s medicine, ‘quick witted, bold, no way shame-fac’d, furious, hasty, quarrelsome, fraudulent, eloquent, courageous, stout-hearted Creatures’.24 In some respects at least, this appears to be an accurate portrait of Harvey, who was certainly quick-tempered. According to one gossip, as a youth he carried a dagger with him, and was apt to draw it ‘upon every slight occasion’.25

Knightrider Street, South of St Paul’s Cathedral (‘Poles church’), as shown on late 16th century ‘Agas’ map of London.

He presumably turned up at the College unarmed, and, being a stickler for decorum, dressed respectfully (but not fashionably – he disliked fashion, considering it a ‘redundant covering, a fantastic arrangement’).26 He was the only candidate to be interviewed that day, leaving plenty of time for a rigorous examination. There were four parts, usually conducted over three or four separate sessions, all based on the works of Galen. They covered physiology, pathology (the symptoms, ‘signs’ and causes of disease), methods of treatment, and ‘materia medica’ (pharmacy). Examinees were then given three questions chosen at random by the President, and asked to cite passages in the works of Galen that answered them. The entire proceedings were conducted orally in Latin.27

Being his first appearance, Harvey was probably examined on physiology and, thanks to his time at Padua, was likely to have acquitted himself well. It would be nearly a year before he was next examined, perhaps to give him a chance to gain some practical experience and bone up on the seventeen Galenic treatises on the College’s reading list. He faced the Censors three times in 1604: on 2 April, 11 May, and finally on 7 August, when he was elected a candidate. This meant he was free to practise and, after four years, would become a full Fellow.

Harvey climbed London’s monumental medical hierarchy with the deftness of a steeplejack. Four months after becoming a candidate, he married Elizabeth, the daughter of a former College Censor and royal physician, Dr Lancelot Browne. Very little is known about Elizabeth, not even the year of her death, which was some time between 1645 and 1652. She apparently bore no children, and contemporaries who wrote about Harvey do not even mention her. Thomas Fuller, in his Worthies of England, published five years after Harvey’s death, described him as ‘living a Batchelor’.28 Harvey never wrote about Elizabeth, except in connection with her pet parrot. He evidently spent hours resentfully scrutinizing the creature, ‘which was long her delight’, noting how it had ‘grown so familiar that he was permitted to walk at liberty through the whole house’.

Where he missed his Mistress, he would search her out, and when he had found her, he would court her with cheerful congratulation. If she had called him, he would make answer, and flying to her, he would grasp her garments with his claws and bill, till by degrees he had scaled her shoulder … Many times he was sportive and wanton, he would sit in her lap, where he loved to have her scratch his head, and stroke his back, and then testify his contentment, by kind mutterings and shaking of his wings.

The flirtations finally ceased when the bird ‘which had lived many years, grew sick, and being much oppressed by many convulsive motions, did at length deposit his much lamented spirit in his Mistress’s bosom, where he had so often sported’. Harvey exacted his revenge on the pampered pet by performing a prompt dissection. Perhaps because of its adoring relationship with his wife, he had assumed it to be a cock, so was surprised to discover a nearly fully formed egg in its ‘womb’.29

Elizabeth’s influential father wasted no time in trying to advance his new son-in-law’s career. In 1605, he heard that the post of physician at the Tower of London was about to come vacant and wrote at least twice on Harvey’s behalf to the King’s secretary of state, Robert Cecil, the Earl of Salisbury, once in haste from an apothecary’s shop in Fenchurch Street, where he was presumably ordering up prescriptions. The application failed, but by 1609, his son-in-law was sufficiently well placed with the royal household to receive a letter of recommendation from the King proposing Harvey for the post of hospital physician at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in Spitalfields. St Bart’s (as it was and still is known) was one of only two general hospitals in London that survived the Reformation, the other being St Thomas’s in Southwark (Bethlehem Hospital, or ‘Bedlam’, north of Bishopsgate, was a lunatic asylum). Its role was to offer hospitality, including free medical care, to London’s poor ‘in their extremes and sickness’. This was an immense task at a time when London’s population was ravaged by some of the highest mortality rates in the country, and swelled by influxes of migrants. St Bart’s had around two hundred beds, cared for by a ‘hospitaler’ (a cleric, who also acted as gatekeeper), a matron, twelve nursing sisters, and three full-time surgeons. The physician’s job was to visit the hospital at least one day a week, usually a Monday, when a crowd of patients would await him in the cloister, ready to be assessed and treated when necessary. In return, he was provided with lodgings, a salary of £25 a year (approximately four times the annual living costs of a tradesman such as a miller or blacksmith) plus 40s. for the all-important livery of office.30

Harvey was offered the job in October 1609. At around the same time he was admitted as a full Fellow of the College of Physicians, confirmed with the publication in the College Annals of the list of Fellows according to ‘seniority and position’, which placed him twenty-third.31

As well as providing a regular salary, the position at St Bart’s proved fruitful in introducing new clients, as influential courtiers often found it convenient to call upon the hospital’s medical staff when they were ill. In early 1612, the most powerful politician of them all, Robert Cecil, was laid low ‘by reason of the weakness of his body’, a reference to a deformity described unflatteringly by one enemy as a ‘wry neck, a crooked back and a splay foot’. According to the courtier John Chamberlain, ‘a whole college of physicians’ eagerly crowded around Cecil’s sick-bed, Sir Theodore de Mayerne, James I’s personal physician, being ‘very confident’ of success, ‘though he failed as often in judgement as any of the rest’. Treatment was hampered by a disagreement over diagnosis, which within a fortnight changed ‘twice or thrice, for first it was held the scorbut [scurvy], then the dropsy, and now it hath got another Greek name that I have forgotten’. Harvey and his surgeon, Joseph Fenton, were then summoned from St Bart’s and were deemed to have done ‘most good’ in treating the condition, Fenton particularly, though neither managed a cure, as Cecil died two months later – probably of the disease originally diagnosed, scurvy.32

In 1613, Harvey took a further step towards the summit of his profession by offering himself for election as a Censor, one of the key positions in the College hierarchy. He attended his first session on 19 October and made an immediate impact. He and his three colleagues, Mark Ridley, Thomas Davies, and Richard Andrews, examined the case of one Edward Clarke, who had given ‘some mercury pills to a certain man named Becket, which caused his throat to become inflamed and even spitting ensued’. Dr Ridley, a veteran Fellow and serving his sixth term as a Censor, demanded a fine of £8, much higher than usual (apothecaries and other medical tradesmen were typically fined around forty shillings; fines of £5 or more were usually reserved for foreign physicians who set up practice in London without a licence). The distinguished scholarly physician Dr Davies, less active in College affairs and serving his third term as a Censor, objected that this was too severe a punishment for a first offence. Then Harvey, uninhibited by his lack of experience, intervened. He backed Ridley, arguing that such ‘ill practice’ demanded an exemplary punishment. However, he conceded Clarke’s fine should be ‘remitted’, reduced, on account of his ‘submission’ to the College, though he should be imprisoned if he failed to pay it. In November, Harvey further demonstrated his zest for discipline and standards by apparently insisting that an applicant for a licence to practise be examined three times on the same day.

And so the meetings continued, week after week, considering case after case, imposing fine upon fine. In December, a Mr Clapham, an apothecary of Fenchurch Street, was brought before the Censors, charged with, among other things, selling an unauthorized medicine ‘for the stone’. Kidney stones were one of the most common complaints physicians had to deal with, and many doctors, including Harvey, had their own secret and lucrative remedies for treating them. Mr Clapham omitted to mention that he sold his own formula and, being ‘reminded’ of it by the Censors, ‘confessed that he often accepted five shillings for this’. In response to questions about its recipe, he was oddly specific about the absence of ‘distilled goats’ milk’, possibly because this would reveal the origin of his recipe and open him to further charges. As well as Mr Clapham, another apothecary, Peter Watson of St John’s Street, was asked to produce copies of four prescriptions he had made up, two of which had not been written by a physician.

The records are sketchy but suggest that, in the year Harvey served his first term as a Censor, he enthusiastically enforced, if he did not actually initiate, one of the most comprehensive crackdowns on unlicensed practitioners to date. The main target was the apothecaries, whose combination of medical experience and knowledge of medicines made them a particularly potent threat to the physicians’ monopoly. During this period, as many as one in ten of the capital’s hundred and twenty or so practising apothecaries were summoned before the Censors, to receive a reprimand if they were lucky, a heavy fine and threat of imprisonment if they were not.33 They seemed to lurk everywhere, down every alley, on every corner, in every backroom. The Censors heard their mocking laughter at the College’s impotence echo through the streets.

As well as threatening the health of the capital’s citizens, these insolent quacks undermined the dignity of the College, at a time when it was preparing to move from its cramped rooms in Knightrider Street to prestigious headquarters next to St Paul’s Cathedral, at Amen Corner – a fitting address for an institution that considered itself the last word in medical expertise. From their grand new premises, they decided it was time to step up their campaign by making a direct appeal to the sovereign.

Harvey was still too junior a member of the King’s household to take on this role, so it was entrusted to a more senior royal physician, Dr Henry Atkins. In early 1614 Atkins was enlisted to whisper the College’s grievances into King James’s ear during one of their routine consultations. On 23 May 1614, the College called an emergency Comitia so that Atkins ‘might inform them what he had done on our behalf before the most serene King’. He ‘reported much’ about his discussions, but did not want to have his words recorded in the Annals, presumably because he felt it might compromise royal confidentiality. His unrecorded remarks encouraged the Fellows, Harvey among them, to draft a letter to the King, entreating James, ‘the founder of the health of the citizens’, to ‘cure this distress of ours, and deign to understand the paroxysms and symptoms of this our infirmity’. The letter reminded the King that under ‘royal edicts … the audacity of the quacks, and the wickedness of the degraded were committed to our senate for correction and punishment’. But the writ of the College was now routinely flouted. ‘They fling scorn and all things are condemned’, particularly by the apothecaries, who ‘ought to be corrected: for as we minister to the universe so they are the attendants of the physicians’.34

Their proposed remedy was to support a move to separate the apothecaries from the Grocers’ Company – the reverse of the manoeuvre used to control the surgeons. The College had little influence over the Grocers, but might have over a company of apothecaries, as long as its founding charter established the physicians’ superiority, which existing legislation only ambiguously supported. Their wish was to be granted, despite the protests of the grocers themselves and of the City authorities, who feared the new apothecaries’ company would, like the College, fall outside their influence.

The new Society of Apothecaries was granted its charter on 6 December 1617, after a great deal of wrangling between the College, the Grocers, the City, and the royal court’s law officers. As a sop to the City, it was agreed that the Society should operate as a guild, with the same organization as other livery companies, having powers to bind apprentices to masters, and free them once they had completed their apprenticeship, and to police the practice of its trade. The doctors also agreed to observe the Society’s monopoly by refraining from making and selling medicines themselves. However, unlike the other guilds, it was not to be regulated by the City fathers. Instead, it fell under the supervision of the College, which was given powers to intervene in crucial aspects of the Society’s business: the passing of by-laws, the ‘freeing’ of apprentices when they completed their term, and the searching of shops.

Another important provision was that apothecaries would have to make their medicines according to a standard set of recipes set out in a ‘London Antidotary’ or dispensatory, drawn up by the College: a bible of medicine.

Bergamo in Italy and Nuremberg in Germany had long used official dispensatories that prescribed exactly how medicines were to be made by apothecaries trading within their borders. Now that the apothecaries of London were to be constituted as a separate body, the College of Physicians decided it was time, after years of discussion, to introduce one of its own.

They did not do a very good job of it. In 1614, a group of Fellows were appointed to produce a draft. Two years later, on 14 September 1616, a meeting was called to review progress. It turned out that very little work had been done. Papers were missing, and there were complaints that the Fellows given the task ‘went away leaving the matter unfinished’.35 After bouts of recrimination, another committee, with Harvey probably among its members, was set up to complete the project. A year later, it was sufficiently advanced for a draft to be handed to a delegation of apothecaries for consultation – a rare moment of cooperation between the two bodies. In January 1618, the publisher John Marriot was given permission to register the title with the Stationers’ Company, giving him an exclusive right to sell the work on the College’s behalf. Marriot would go on to publish the likes of John Donne, but at the time of his appointment by the College, he had only recently set up shop at the sign of the White Flower de Luce, in St Dunstan’s Churchyard. The College presumably hoped that commercial dependence would make such a callow operator more tractable. They were wrong.

On 26 April 1618, a royal proclamation was circulated ordering all apothecaries, who were then in the throes of forming their Society, to buy the new book, to be published in Latin under the title Pharmacopoeia Londinensis.36 In May, the more eager and obedient queued up at the sign of the White Flower de Luce to buy copies. Some of these early copies were discovered to have a blank page where the King’s Proclamation should have been and so had to be withdrawn. The Proclamation that appeared in the amended editions was the only section of the book in English, to ensure its message was understood. The King, it announced verbosely, did ‘command all and singular Apothecaries, within this our Realm of ENGLAND or the dominions thereof, that they and every of them, immediately after the said Pharmacopoeia Londin: shall be printed and published: do not compound, or make any Medicine, or medicinal receipt, or praescription; or distil any Oil, or Waters, or other extractions … after the ways or means praescribed or directed, by any other books or Dispensatories whatsoever, but after the only manner and form that hereby is, or shall be directed, praescribed, and set down by the said book, and according to the weights and measures that are or shall be therein limited, and not otherwise &c. upon pain of our high displeasure, and to incur such penalties and punishment as may be inflicted upon Offenders herein for their contempt or neglect of this our royal commandment’.37

The book was, compared with the continental dispensatories upon which it was modelled, concise and simple. Unfortunately, its ‘manner and form’ was, according to its own authors, defective. The College claimed that Marriot had ‘hurled it into the light’ prematurely. Dr Henry Atkins, the royal physician who had first approached the King about the apothecaries and was now the College’s President, had returned from a trip to the country to find, ‘with indignation’, that the work to which he and the College had ‘devoted so much care … had crept into publicity defiled with so many faults and errors, incomplete and mutilated because of lost and cut off members’.38 A meeting was hastily convened at Atkins’s house, and it was decided that the book should be withdrawn from publication and a new edition issued.

Marriot published this ‘second endeavour’ in early 1619 (though the publication date remained 1618, to obscure the first endeavour’s existence). The fact that Marriot, rather than another publisher, was selected to do the job seems to contradict the College’s claim, in a new epilogue, that he was to blame for the premature release of the defective first edition. So did the news, reported at a Comitia on 25 September 1618, that Marriot was still awaiting material from the College and that he had been promised a further payment ‘when the corrected book appeared’.39

An examination of the differences between the two editions confirms that the need for a reissue had little or nothing to do with printing mistakes or the publisher. The second edition is a substantially different work, containing over a third more recipes. And far from eliminating errors, it introduced several of its own. The real reason for the reissue appears to have been an editorial dispute within the College over the contents. The bulk of the recipes it contained were Galenicals – medicines based on Galen’s writings and drawn from ancient Greek, Roman, and Arabic pharmacopoeias, most dating back to the early centuries ad. However, ten pages of novel ‘chemical’ medicines were also included. Some of the traditionalists in the College probably objected to this and tried to have them removed, in the process provoking a review of the book’s entire contents. When the College, in a metaphorical frenzy, accused the printer of snatching away the manuscript ‘as a blaze flares up from a fire and in a greedy famine deprives the stomach of its still unprepared food’, it was using him to draw the heat from disputes within its own profession.40

Harvey’s involvement in the drafting of the dispensatory is undocumented. However, he is listed as one of its authors, bearing the title Medicus Regis juratus, which shows that by 1618, aged forty, he had become a member of King James’s medical retinue, placing him near the peak of his profession. However, posterity would remember him not for his dazzling rise, nor for his contribution to the botched Pharmacopoeia, but for another achievement made over this period.

In 1615, Harvey was appointed the College’s Lumleian Lecturer in Anatomy, succeeding his fellow Censor Dr Thomas Davies, who had held the post since 1607. The lectureship had been founded in 1582 by Lord Lumley to advance England’s ‘knowledge of physic’.41 Attendance for College Fellows was mandatory, twice a week for an hour through the year, though they came reluctantly, the College at one stage being forced to more than double the fine for nonattendance to 2s. 6d.

Harvey was well qualified for the post. Unlike many of his colleagues, he was an enthusiastic and unflinching anatomist. At various stages in his career he performed or witnessed dissections of cats, deer, chickens, guinea-pigs, seals, snakes, moles, rats, frogs, fish, pigeons, an ostrich, his wife’s parrot, a pet monkey, a human foetus, his father, and his sister. It has been estimated that he cut up 128 species of animal as well as numerous humans. His autopsies revealed the size of his father’s ‘huge’ colon, his sister’s ‘large’ spleen (which weighed five pounds), and the condition of the genitalia of a man who was claimed to have died at the age of a hundred and fifty-two, which, as Harvey reported to the King, was entirely consistent with a prosecution for fornication the subject had received after turning a hundred.42

Harvey looked upon anything that moved as potential material, complaining during a journey to the Continent in 1630 that he ‘could scarce see a dog, crow, kite, raven or any bird, or anything to anatomise, only some few miserable people’.43 London in the early seventeenth century would provide a richer source of specimens, both human and animal. The aviary in St James’s Park had ostriches and parrots; merchants arrived from the East Indies with monkeys and snakes; and the streets were packed with a ready supply of feral dogs and cats. He and his colleagues also had access to a supply of human specimens taken from the scaffolds at Tyburn and Newgate, the traditional places of execution. Examining bodies freshly taken down, and noting how they were soaked in urine, he opened them up while the noose was still tight, in the hope of examining the organs before the final signs of life were extinguished.44

Harvey’s Lumleian lectures began in December 1616, and they were masterpieces. His lecture notes have, unlike most of his other papers, survived, proudly introduced by a title-page upon which he inscribed in red ink, in Latin, ‘Lectures on the Whole of Anatomy by me William Harvey, Doctor of London, Professor of Anatomy and Surgery, Anno Domini 1616, aged 37’. Presumably to guard against casual perusal, the notes that follow are written in the barely legible scrawl for which future generations of physicians were notorious. Though the bulk are in Latin (not very good Latin), they are peppered with fascinating case studies and bawdy asides, all in the vulgar tongue. He poked fun at ‘saints’ – Puritans like William Attersoll – for their calloused knees, the stigmata of their overearnest piety.45 He told the story of Sir William Rigdon, whose stomach filled with yellow bile, as a result of which he died hiccoughing. He noted that ‘in [men with] effeminate constitution the breasts [may be enlarged]; and in some milk’, citing as an example Sir Robert Shurley (c.1518–1628), envoy to the Shah of Persia and a kinsman of William Attersoll’s patron. Commenting on the anatomy of the penis, he noted that Lord Carey, presumably another aristocratic client, had a ‘pretty bauble, a whale’, and that a man who lived ‘behind Covent Garden’ to the west of the City had one ‘bigger than his belly … as if for a buffalo’.46 He observed how ‘fecund’ the penis is in ‘giving birth to so many names for itself: twenty in Greek, sixteen in Latin. He dwelt on the nature of sexual urges, estimating that a healthy man can achieve up to eight copulations a night, though ‘some lusty Laurence will crack … 12 times’. ‘Few pass 3 in one night,’ he added, more realistically.47 He also asserted that males ‘woo, allure, make love; female[s] yield, condescend, suffer – the contrary preposterous’. There were not, of course, any women in Harvey’s audience to challenge these assertions.48

The lectures were broken into three ‘courses’ performed ‘according to the [hour]glass’, in other words to a strict schedule: ‘1st lower venter [belly], nasty yet recompensed by admirable variety. 2nd the parlour [thorax or chest]. 3rd divine Banquet of the brain.’49 The first course was completed in December 1616, the second in January 1618, the third, the ‘divine Banquet of the brain’, in February 1619. The exact date of the lectures depended on the availability of specimens and the weather, which had to be cold enough to prevent the body from decomposing before the dissection was complete.50 Harvey reckoned that in the right conditions he had three days to complete a lecture before the body would start to ‘annoy’.51

The proceedings would have been conducted with ceremony and decorum. Harvey was no foppish ‘gallant’ and disliked fancy clothes – ‘the best fashion to leap, to run, to do anything [is] strip [ped] to ye skin,’ he would tell his audience during the section on the epidermis.52 Nevertheless, he would have felt obliged to wear a purple gown and silk cap, the College livery for such occasions. He also carried a magnificent whalebone probe tipped with silver, which he used to point out parts of the body.

His lectures would begin with a few philosophical observations. Harvey adopted the strictly scholastic view of anatomy, that it was first philosophical (concerned with revealing universal truths about nature and the cosmos), then medical (demonstrating medical theory), and finally mechanical (showing how the body worked). When it came to the philosophy, Harvey’s authority was Aristotle, his intellectual hero. Aristotle taught that knowledge was derived from observation and experimentation. He also taught that the cosmos had an order and unity. Every physical entity, including every organ of the body, had its place and purpose in this greater scheme, which he called nature. ‘The body as a whole and its several parts individually have definite operations for which they are made,’ he wrote in On the Parts of Animals.53 Time and again in his lectures, Harvey would remind his audience of this. ‘Nature rummages as she can best stow’ in the way she arranges the organs, ‘as in ships’, adding that this arrangement was upset during pregnancy by ‘young girls … lacing’ their girdles too tight, which was why they should be told to ‘cut their laces’. Nature had also created ‘divers offices and divers instruments’ in the digestive tract, so that it could act like a chemical still, with ‘divers Heats [temperatures], vessels, furnaces to draw away the phlegm, raise the spirit, extract oil, ferment and prepare, circulate and perfect’. Considering genitalia, he noted that nature made sex pleasurable, even though it was ‘per se loathsome’. This was so that humans could produce ‘a kind of eternity by generating [offspring] similar to themselves through the ages’. Harvey, whose marriage produced no children, added in a strikingly poetical aside that we are ‘by the string [umbilical cord] tied to eternity’.54

Having covered the philosophical issues, he would move on to the medical ones. His lecture on the thorax would thus begin with some general and orthodox remarks about its function and anatomy, quoting Galen’s observation that the chest provides for the heart, lungs, respiration, and voice. Before it was cut open, he would invite the audience to note the flatness of the human thorax compared to that of the ape and dog, which protrude like a ship’s keel.

Then he threw out a question to his audience: What is the connection between the width of the chest and the ‘heat’ or vital spirit of the animal? ‘Wherefore [do] butterflies in the summer flourish on a drop of blood?’ Because, would come the answer, the heart and lungs act like a furnace, heating the blood that suffuses energy through the body. The potency of that blood is demonstrated by its effect on the cold-blooded butterfly. ‘Especially in the summer the newt is hotter than the fish,’ he added, gnomically.

The shape of the chest also revealed important truths about rank. Roman emperors, Harvey noted, were distinguished by having broad chests, which explained their exceptional ‘heat, animation [and] boldness’. His authority for this claim was the Roman biographer Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, though the only broad chest mentioned in Suetonius’ On the Lives of the Caesars was that of the ‘well chested’ Tiberius, better known for his hot pursuit of young boys than political or military objectives.55

With the medical remarks concluded, it was the time to open up the body, and reveal the mechanics. Traditionally, physicians did not perform the actual dissection, leaving that job to a surgeon. But Harvey believed in getting his hands dirty. His method was to start with the general and work towards the specific, ‘shew as much in one observation as can be … then subdivide according to sites and connections’. Speed and dexterity were essential, not just to complete the course before the body began to putrefy, but to prevent the audience from losing the thread of the argument. There was no time to ‘dispute [or] confute’. ‘Cut up as much as may be,’ he commanded, ‘so that skill may illustrate narrative.’56

Harvey evidently enjoyed playing on the squeamishness of his audience. As a waft of flatus permeated the room, he would recall for the assembled physicians, many of whom had no practical experience of dissections, how cutting up parts of the body, particularly of abscessed livers, provoked ‘nausea and loathing and stench’. The interior of the chest would prove less noxious than the liver, however. Cutting through the ‘skin, epidermis, membrana carnosa’, penetrating ‘sternum, cartilages, ribs’, piercing ‘breasts, nipples, emunctory [lymphatic] glands’,57 touching upon respiration, ingestion, hiccoughs, and laughter – prompting a digression on Aristotle’s observation ‘that when men in battle are wounded anywhere near the midriff, they are seen to laugh’ – he would finally come to the pericardium. This was the ‘capsule’ surrounding the heart.58 He would make some remarks about the structure and use of the pericardium, and respectfully correct errors made by Vesalius relating to the mediastinum (the compartment between the lungs). He discussed the humour or fluid which ‘abounds’ within the percardial sac, a liquid like ‘serum or urine’, which is ‘provided by nature lest the heart become dry; therefore water rather than blood [issued] from Christ’s wounds’, adding that it was ‘wasted away … in persons hanged in the sun’. Then he revealed the organ within.

The heart prompted Harvey into raptures. Other organs were usually described with clinical detachment, but not this one. The ‘empire of the heart’ was ‘the principle part of all … the citadel and home of heat, lar [household god] of the edifice [; the] fountain, conduit, head’ of life: ‘All things are united in the heart.’ Then his notes contain what appears to be an innocuous observation, scribbled next to his initials: ‘Query regarding the origin of the veins. I believe from the heart.’ It was the first sign of the intellectual convulsion to come.59

Fundamental to Galen’s physiology was the belief that the veins originate in the liver. Harvey’s dissection showed that this was not the case, but was ‘an error held now for 2000 years’. He did not say this lightly. ‘I have given attention to it,’ he added, ‘because [it is] so ancient and accepted by such great men.’60 His notes are ambiguous, but suggest that at some point a live animal was brought into the room, probably stunned with a blow to the head, and strapped to the table for vivisection.61 Only by such means could Harvey show the audience what he wanted them to see: the beat of a living heart lying in the watery reservoir of pericardial humour. The movements of this glistening organ were complex. He had gazed upon it ‘whole hours at a time’. Initially he had been ‘unable to discern easily by sight or touch’ how it worked, but, by watching the heart as the animal gradually expired, as the muscles began to slacken and the heartbeat slowed, he beheld a revelation, which he now wanted to share with his audience in the most compelling fashion possible. ‘Observe and note,’ he instructed. ‘It seems to me that what is called diastole is rather contraction of the heart and therefore badly defined … or at least diastole [is] distension of the fleshiness of the heart and compression of the ventricles.’62

Galen saw ‘diastole’, the phase of the heart’s beat when it expands, as the active phase, when it mixes pneuma, or vital spirit, from the lungs with blood to vivify it. Systole, the phase when the heart contracts, was when it relaxed. Galen further concluded that, since the pulse of the arteries did not synchronize with the diastole phase, they must pulse of their own accord, in a manner similar to the ‘pulse’ of the intestine passing food through the digestive system.

Harvey turned this idea upside down. He argued that the active phase was systole, when the heart contracted, pushing out the blood that had flowed into the heart’s chambers, or ventricles, during diastole. The pulse was thus not ‘from an innate faculty of the arteries, as according to Galen’, but the pressure wave produced by the heart pumping blood at high pressure into the arteries, which explained why they had walls thicker than those of veins.63 ‘From the structure of the heart it is clear that the blood is constantly carried through the lungs into the aorta as by two clacks of a water bellows to raise water,’ Harvey concluded. He was referring to the system of valves used to fill a pair of bellows with water, which is then squirted out under pressure.

He used another experiment to show where the blood goes to once it has left the heart. Physicians were familiar with applying ‘bandages’ (tourniquets) to the upper arm for blood-letting. They would know how a tourniquet applied very tightly would cut off both veins (which run just beneath the surface of the skin) and arteries (which are deeper in the arm), while a looser tourniquet would restore the flow of the arteries (indicated by the return of the pulse in the wrist) but not of the veins. Harvey noted that when the tourniquet is applied at its tightest, the hand would turn cold, but when it was loosened sufficiently to restore flow through the arteries it would become flushed and swollen, with the veins standing out. The hand would remain in that state while the tourniquet remained in place, with no sign of the engorgement dispersing, which is what would have been expected if the venal blood was consumed. But when flow was restored to the veins by releasing the tourniquet altogether, the swelling would disappear instantly. Thus, ‘by [application of] a bandage it is clear that there is a transit of blood from the arteries into the veins, whereof the beat of the heart produces a perpetual circular motion of the blood’. In other words, blood did not seep out into the extremities of the body to be turned into living tissue, but circulated around, pumped by the heart. This meant that Galen was wrong, not only about the heart, but about the liver also, and it raised serious questions about the role of blood. If it was not the fuel that fed as well as animated the body, what was it for? On this, Harvey for the time being held to the Galenic belief that it was something to do with delivering ‘natural heat’, the vital spirit that animated the body. The heart’s two chambers were ‘two cisterns of blood and spirit’, as he put it, and the role of the circulation was to ensure the even distribution of these products through the body.64

Charles Darwin wrote to a friend that to publish his theory of evolution by natural selection was ‘like confessing to a murder’.65 Harvey’s confession was no less dangerous. According to the dating evidence of his lecture notes, he first explained his theory in January 1618. This was eight years after Galileo, who had held the chair of mathematics at Padua at the time Harvey had studied there, had used a telescope to confirm Copernicus’ theory that the earth went round the sun, and just three years after the Catholic Inquisition had formally declared Copernicanism to be heretical. And it was only eighteen years after the philosopher and mystic Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake in Rome for suggesting, among other speculations, that the blood must go round the body as the planets go round the sun.

Harvey faced no such extreme reaction to his theory. In fact, there was barely any reaction at all, merely a respectful hush. This was partly because, though the lectures were in public, no one reported on them, and their content would not be published by Harvey himself for another decade. But, given the College’s commitment to Galen, and its harsh treatment of anyone who failed to follow his principles, some sort of expression of shock might have been expected from his colleagues. There was none. There is not a single mention of the idea in the College Annals for the period, merely lengthy discussions about the chaotic publication of the Pharmacopoeia, the discovery of yet more ‘impure’ medicines during searches of the apothecaries’ shops, and arrangements for the College’s annual feast.

This silence may have been because so few of the Fellows bothered to come to the lectures, or because so few understood them. More likely, it was because Harvey realized from the beginning the political as well as medical implications of his ideas. He did not at this stage spell them out, but they are evident in his discussions about the relative importance of the heart versus the brain.

Despite references to bellows and cisterns, Harvey was emphatic that the heart was no mere mechanical pump. He kept to the principle that it was the body’s most important organ, the ‘source of all heat’, that the ‘vital spirits are manufactured in the heart’, invigorating the blood to keep the body alive.66 However, when he came to his final lecture, the ‘banquet of the Brain’, he ran into difficulties sustaining this position. The cerebrum, he pronounced, was ‘the highest body in a very well-protected tower; hair, skin &c., as safeguards, so that nature [protects] no part more’. Having reached this conclusion, he paused for thought, as though realizing too late that he had compromised the primacy of the heart. This prompted the assertion that the brain was ‘not to be compared with the heart’. But he could not resist trying, provoking a Herculean struggle to reconcile the importance of one with the ingenuity of the other:

The empire of the heart extends more widely in those [creatures] in which [there is] no brain. Perhaps more worthy than the heart, but the heart is necessarily prior … All animals have one most perfect part; man [has] this, excelling all the rest; and through this the rest are dominated; it is dominated by the stars wherefore the head [is] the most divine, and to swear by the head; sacrosanct; to eat [the brain is] execrable.67

Why did he expend so much effort deliberating on this anatomically trivial rivalry? The reason partly revealed itself in some subsequent remarks about the relative sizes of organs in different animals. The human body, he noted, was like a ‘commonwealth’, with different organs being the different branches of state, each having its function, each having its divinely ordained place. ‘Politicians,’ he added, can acquire ‘many examples from our art’, in other words from anatomy. 68 And with this, he left the matter tantalizingly suspended.

As the body politic began to disintegrate, he would return to this issue. And he would argue that his revelations about the heart, far from overturning the existing order, reinforced it.