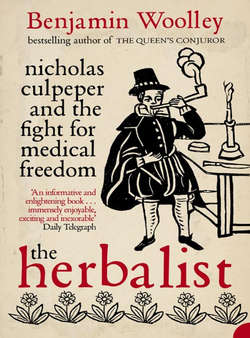

Читать книгу The Herbalist: Nicholas Culpeper and the Fight for Medical Freedom - Benjamin Woolley - Страница 8

ANGELICA Angelica archangelica

ОглавлениеIn times of Heathenism when men had found out any excellent Herb &c. they dedicated it to their gods, As the Bay-tree to Apollo, the Oak to Jupiter, the Vine to Bacchus, the Poplar to Hercules: These the Papists following as their Patriarchs, they dedicate them to their Saints, as our Ladies Thistle to the Blessed Virgin, St. Johns Wort to St. John, and another Wort to St. Peter, &c.

Our Physitians must imitate like Apes, (though they cannot come off half so cleverly) for they Blasphemously call Pansies, or Hartseas, an Herb of the Trinity, because it is of three colours: and a certain Ointment, an Ointment of the Apostles, because it consisteth of twelve Ingredients; Alas poor Fools, I am sorry for their folly, and grieved at their Blasphemy …

[Angelica] resists Poison, by defending and comforting the Heart, Blood, and Spirits, it doth the like against the Plague, and all Epidemical Diseases if the Root be taken in powder to the weight of half a dram at a time with some good Treacle in Cardus Water, and the party thereupon laid to sweat in his Bed. If Treacle be not at hand, take it alone in Cardus or Angelica Water.

The Stalks or Roots candied and eaten fasting are good Preservatives in time of Infection; and at other times to warm and comfort a cold Stomach. The Root also steeped in Vinegar, and a little of that Vinegar taken sometimes fasting, and the Root smelled unto is good for the same purpose …

According to Grieve, in early summer-time, peasants living around the lakelands of Pomerania and East Prussia, where Angelica grew plentifully, marched into the towns carrying the flower-stems chanting songs ‘so antiquated as to be unintelligible even to the singers themselves’, the relic of some pagan festival. According to Christian legend, the plant’s ability to cure the plague was revealed in a dream by an angel. Another explanation of the name of this plant is that it blooms on 8 May (Old Style), the day associated with an apparition of Michael the Archangel at Monte Gargano in Italy.

The candied stems are used as cake decorations.

In the spring 1625, King James, approaching his sixtieth birthday, ‘retired for fresh air and quietness to his manor at Theobald’s’, his country retreat in Hertfordshire, built by Elizabeth’s chief minister William Cecil. In March, he fell ill with a ‘tertian fever’, malaria, and was confined to a sickroom at the house, which later was formally dubbed his ‘Chamber of Sorrows’. As he lay there, he was attended by a busy swarm of courtiers, servants, and medics, bringing documents, linen, and medicines, taking messages, bedpans, and pulses.

Throughout, James’s team of physicians stood by, conferring. They included at least two loyal Scots doctors he had brought with him from Edinburgh when he succeeded to the English throne in 1603, Drs Craig and Ramsay. There was also a sizeable portion of London’s medical élite, including Sir William Paddy, erstwhile President of the College of Physicians, and Dr Henry Atkins, the current President, together with Drs Lister, Chambers, and William Harvey, whose role in the unfolding drama was to be as central as it was obscure.

At this stage, James’s condition gave no cause for alarm, as malarial attacks were common, and in the past the King had managed to fight them off without too much difficulty. As the Venetian ambassador put it in a note to the Doge, ‘His majesty’s tertian fever continues but as the last attack diminished the mischief the physicians consider that he will soon be completely recovered. His impatience and irregularities do him more harm than the sickness.’1 James was a notoriously difficult patient.

However, on Monday, 21 March his condition took an abrupt turn for the worse. In the afternoon he anticipated a seizure, telling his doctors he felt a ‘heaviness in his heart’. The physicians appear to have been undecided on what to do. At about 4 p.m., the royal surgeon, one Hayes, arrived with a strip of soft leather and a box containing a thick syrup. Watched by Harvey, Hayes soaked the leather with the syrup and lay the impregnated ‘plaster’ upon the King’s abdomen. Soon after, the King suffered a series of fits, as many as eight according to one report.2 The plaster was removed. However, later in the evening it was put back, whereupon the King started ‘panting, raving’, and his pulse became irregular. The following day, Tuesday, he went into dangerous decline, and it began to dawn on his medical team that the illness might prove fatal. He was given a soothing drink or ‘posset’ made with gillyflower together with some of the same syrup used to impregnate the plaster, but he complained that it made him ‘burn and roast’. Despite this, he apparently asked for more. Harvey left for London, perhaps to brief officials there. On the road he met John Williams, Bishop of Lincoln and recently made Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, the seal used to ratify documents of state. Harvey informed Williams of the King’s grave state.

On Wednesday night, James suffered another violent fit. Blood was let in the hope of bringing relief. On Friday the plaster was apparently applied again, and in the evening another symptom reportedly appeared: his tongue swelled up to such a size that he could no longer speak clearly. On Saturday the physicians held a crisis meeting, but could not agree on the nature of the King’s illness or how to proceed. The following day, James died.3

Within forty-eight hours, his body was back in London and subjected to a post-mortem. A witness described the procedure:

The King’s body was about the 29th of March disbowelled, and his heart was found to be great but soft, his liver fresh as a young man’s; one of his kidneys very good, but the other shrunk so little as they could hardly find yt, wherein there was two stones; his lights [lungs] and gall black, judged to proceed of melancholy; the semyture of his head [skull] so strong as that they could hardly break it open with a chisel and a saw, and so full of brains as they could not, upon the opening, keep them from spilling, a great mark of his infinite judgement. His bowels were presently put into a leaden vessel and buried; his body embalmed.4

The autopsy confirmed the King’s known problems with recurring urinary infections, kidney stones, and, as the blackened lungs and gall particularly indicated, the predominance of melancholia in his complexion. The surplus of grey matter that burst out of his brain case also provided the King’s subjects with reassuring physiological evidence of his intelligence. But nothing was revealed about the cause of death. Rumours soon began to circulate that he had been poisoned.

Such suspicions were stimulated by widespread anxieties about the state of the court. Many believed it had become rife with corruption and Catholicism, nurtured by James’s favouritism. One man more than any other was seen as the embodiment of such concerns: George Villiers, James’s favourite, whispered to be his lover, ‘raised from the bottom of Fortune’s wheel to the top’.5 Villiers had benefited more than anyone else from royal favours. The son of a sheriff and a ‘servant woman’, Villiers had been elevated by James to Duke of Buckingham in 1623. The last duke in England had been Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, executed in 1572 for his plan to marry Mary Queen of Scots and found a Catholic dynasty to replace Elizabeth’s. Elizabeth, as parsimonious with titles as James was extravagant, and disturbed by having to order the execution of a close kinsman, had thenceforth refused to raise even her closest favourites to a rank traditionally reserved for those with royal blood, and now tainted with treasonous associations.

Such a high position provided the perfect stage for Villiers to play out his political ambitions, which now included arranging the future of James’s son and heir, Prince Charles. The sickly, shy, stammering prince was initially jealous of Villiers’ closeness to the King. When he was sixteen, he had lost one of Villiers’ rings, prompting James to summon his son and use ‘such bitter language to him as forced His Highness to shed tears’. A few months later, during a walk in Greenwich Park, James boxed the boy’s ears for squirting water from a fountain into Villiers’ face.6 But by the later years of James’s reign, loyalties began to shift. Villiers began to lavish his attentions on Charles, who responded by declaring himself Villiers’ ‘true, constant, loving friend’, trusted enough to take charge of his marriage negotiations. Villiers promoted matches first with the Infanta Maria, the daughter of the King of Spain, then Henrietta Maria of France, both Catholic royals. The Puritans, a body with growing influence in the House of Commons, sensed danger, which intensified in May 1625, just two months after Charles had succeeded to the throne, when he married Henrietta Maria by proxy (she was still in France at that stage, Villiers having been dispatched immediately after James’s funeral to fetch her). Fears spread that with her arrival would come a Catholic dispensation and, as the MP John Pym put it melodramatically: ‘If the papists once obtain a connivance, they will press for a toleration; from thence to an equality; from an equality to a superiority; from a superiority to an extirpation of all contrary religions.’7 Thus, when the charges that James had been poisoned first emerged, there were many ready to identify Villiers as the chief suspect, working to hasten the succession of his new best friend.

Suspicions were first voiced by John Craig. Being a Scottish doctor, he had initially practised in London without a licence but had agreed to submit himself to examination by the College of Physicians, appearing before the Censors on 2 April 1604 alongside Harvey, who was receiving his second examination that day. Unlike Harvey, Craig was admitted immediately, despite being a Scot and therefore according to the College’s own statutes ineligible for membership. Craig had very little to do with the College thereafter, devoting himself almost exclusively to the King.

It was in the early days of James’s final illness that Craig’s suspicions were aroused. Villiers’ mother, the Countess of Buckingham, had taken it upon herself to nurse the King, and, Craig claimed, it was she who first applied a plaster to the King’s stomach without the permission of James’s attending physicians. Her intervention ‘occasioned so much discontent in Dr Craig, that he uttered some plain speeches, for which he was commanded out of court’. He was escorted from Theobalds and banned from returning to James’s side, and from further contact with Charles.8 Soon after, he accused the Countess and her son the Duke of poisoning the King.

Aspects of Craig’s story were confirmed by others who were present in the ‘Chamber of Sorrows’. Thomas Erskine, Earl of Kellie, a Villiers supporter who was at Theobalds throughout, wrote in a letter dated 22 March 1625 to his kinsman John Erskine, Earl of Mar: ‘There is something fallen out here much disliked, and I for myself think much mistaken, and that is this. My Lord of Buckingham, wishing much the King’s health caused a plaster to be applied to the King’s breast, after which his Majesty was extremely sick, and with all did give him a drink or syrup to drink; and this was done without the consent or knowledge of any of the doctors; which has spread such a business here and discontent as you would wonder.’9

The accusation became public some months later in a pamphlet by George Eglisham (or Eglington), doctor to James Hamilton, the Earl of Abercorn. Eglisham also claimed to have treated the King on various occasions over the previous ten years. He was not apparently in attendance during the King’s final days, though he may have been at Theobalds in mid-March. He alleged that Villiers, having seen that ‘the King’s mind was beginning to alter towards him’, decided it was time for James to ‘be at rest’ so his son could inherit. When the King fell sick ‘of a certain ague, and in that spring [infection], was of itself never found deadly, the Duke took his opportunity when all the king’s Doctors of Physic were at dinner, upon the Monday before the King died, without their knowledge and consent, offered him a white powder to take: the which he a long time refused; but overcome with his flattering importunity at length took it in wine, and immediately became worse and worse, falling into many swoonings and pains, and violent fluxes of the belly so tormented, that his Majesty cried out aloud of this white powder, would to God I had never taken it, it will cost me my life’. The following Friday, Villiers’ mother was involved in ‘applying a plaster to the King’s heart and breast, whereupon he grew faint, short breathed, and in a great agony’. The smell of the plaster attracted the attention of the physicians, who, returning to the King’s chamber, found ‘something to be about him hurtful unto him and searched what it should be, found it out, and exclaimed that the King was poisoned’. Buckingham himself then intervened, threatening all the physicians with exile from the court ‘if they kept not good tongues in their heads’. ‘But in the mean time,’ Eglisham added, ‘the King’s body and head swelled above measure, his hair with the skin of his head stuck to the pillow, his nails became loose upon his fingers and toes’ – signs, perhaps, of poisoning by white arsenic or sublimate of mercury, substances implicated in another courtly scandal fresh in the public mind, the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury in 1613. As to the source of the poison, Eglisham’s finger pointed straight at Buckingham’s astrologer, ‘Dr’ John Lambe. Lambe had become a figure almost as hated as his master, accused of performing ‘diabolical and execrable arts called Witchcrafts, Enchantments, Charmers and Sorcerers’, and in 1623 of raping an eleven-year-old girl. He also practised medicine, which in 1627 led to him being referred to the College of Physicians by the Bishop of Durham.10

The poisoning allegations were ignored by the new king and his ministers, but taken up by a number of the Duke’s enemies in Parliament. Relations between Charles and Parliament soured within weeks of his accession, as the matter of his subsidy, the amount of tax revenue to be paid into the royal exchequer, was debated. Villiers’ influence over the new king became one of the main points of contention, and it soon emerged that a number of MPs were planning to bring charges against the Duke for his role in instigating a number of extravagant and disastrous policies. The primary role of Parliament was supposed to be debating laws and raising taxes, not sitting in judgement over the court, and the King was outraged by its presumption.

Meanwhile, a terrible epidemic of the plague had broken out in London, forcing the King to take refuge at Hampton Court. Charles wanted Parliament to continue sitting, to ensure it voted the subsidy he desperately needed, so he forced both houses to reconvene in Oxford – a precursor of the government in exile that Charles set up during the Civil War. The reassembled MPs were in no mood to be compliant, and after an angry debate one of them, Sir George Goring, demanded that Villiers be summoned ‘to clear himself’ – in other words, account for the policies he had advised the King to adopt. This produced a furious response from Charles. He summoned his Council and, according to the snippets picked up by the Venetian ambassador, told his ministers he could not tolerate his ‘servants to be molested’ in this manner. ‘All deliberations were made by his command and consent, notably convoking Parliament; he exculpated the Duke of Buckingham; complained that Parliament had wished to touch his own sovereignty; his condition would be too miserable if he could not command and be obeyed.’ These complaints, made within six months of his succession, would set the tone of his entire reign.11

Parliament, however, continued to touch the King’s sovereignty, which became increasingly tender. In the spring of 1626, as Charles still impatiently awaited a settlement on his subsidy, the Commons passed a motion that it would ‘proceed in the business in hand concerning the Duke of Buckingham, forenoon and afternoon, setting all other businesses aside till that be done’. As part of this business, a select committee was appointed to hear the evidence that the Duke had poisoned James.

Only a garbled account of the proceedings survives.12 Several, but not all, of the King’s physicians were called to give evidence. Craig was notably absent, as was Sir William Paddy, the most senior member of the College to have attended the King, and Sir Theodore de Mayerne, James’s principal physician, who had been abroad since 1624. Those who did attend include Dr Alexander Ramsay, one of James’s Scottish doctors; Dr John Moore, a licentiate of the College (i.e. granted a licence to practise) but never admitted as a Fellow because he was publicly identified as a Catholic; Dr Henry Atkins, the current President of the College; Dr David Beton, another Scottish physician; a Dr Chambers, a ‘sworn’ royal physician but not a Fellow of the College; Dr Edward Lister, a veteran of the College and a Censor at the time of Harvey’s admission; and William Harvey. The King’s surgeon Hayes was also called, together with Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, a courtier who was in attendance throughout most of the King’s illness.

All agreed that the Duke had persuaded the King to take a medicine in the form of a posset and a plaster. They also admitted that, soon after the King’s death, they had been asked to endorse a ‘bill’ that was purported to contain the recipe for that medicine. Thereafter, confusion and obfuscation abounded. No one could recall what was in the bill presented to them after the King’s death, or confirm that the recipe was for the medicine given to the King, which implied that they did not know what was in the medicine. Various justifications were offered as to why they allowed an unknown substance to be given to a patient under their care: that they were absent when it was administered, that the King had ordered it to be administered, that they believed it to be safe because it smelt of a theriac or ‘treacle’, specifically Mithridate, an elaborate but familiar medicinal compound which, the doctors reassured the committee, would not have caused any harm in this case.

As to who prepared the medicine, there was little agreement. Some said it was the Duke himself, some that it was the King’s apothecary, one Woolfe. When asked who had been present when the medicine was given, fingers started pointing in many directions, but mostly towards the royal surgeon, Hayes, and the physician in closest attendance at the crucial stages of the King’s illness, William Harvey.

Dr Moore claimed that Harvey had been in attendance when the plaster was first brought in and should have prevented it from being applied. Moore had been identified from the beginning of the inquiry as a Catholic and, as Dr Atkins put it, ‘not sworn’, in other words not officially recognized as a royal physician. He was also forced to admit that it was he who presented the physicians with the supposed recipe for the medicine for their endorsement after the King’s death. This made him more vulnerable than any of the other doctors, and probably explains why he tried to deflect blame in the direction of Harvey.13

Harvey, however, was serene. He admitted to being present when the plaster was applied, the surgeon Hayes performing the operation. He ‘gave way’ to the procedure because it was ‘commended by [the] Duke as good for [the King]’. Furthermore, since it was an external treatment, he could safely monitor its effects from the King’s bedside. Trying to spread the responsibility a little, he pointed out that Dr Lister had been there at the time the plaster was first applied, a claim Dr Lister later denied. As for the posset, Harvey had allowed it to be administered as ‘the King desired it, because the Duke and [Earl of] Warwick had used it’. The select committee notes also add the words ‘He commended the posset’, though whether the commendation was Harvey’s or the King’s is unclear. Harvey confirmed that a recipe had been presented to the physicians soon after James’s death, brought in by Sir William Paddy. However, alone of all the physicians questioned, he suggested that the physicians had ‘approved’ it. Unlike some of his colleagues, Harvey appears not to have questioned whether the recipe was the same as that used to make the medicine. As to its origin, all he would say was that it was a ‘secret of a man of Essex’, referring to a John Remington of Dunmow.14

The question that remained unanswered throughout the proceedings was why a plaster should have been applied at all. Harvey gave a hint – not to the parliamentary select committee, but to Bishop Williams, the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, when the two met on the road from London to Theobalds on the Tuesday before the King’s death. Williams later recalled Harvey describing the illness suffered by the King in these terms: ‘That the King used to have a Beneficial Evacuation of Nature, a sweating in his left Arm, as helpful to him as any Fontanel could be; which of late had failed.’ In other words, there was an area probably around the upper left ribs, where he would sweat copiously, allowing the release of surplus humours that would otherwise accumulate and putrefy in that part of the body. This outlet, Harvey claimed, had become blocked, causing a dangerous build-up of those humours. It was a puzzling diagnosis, as James’s underarm fontanel is mentioned nowhere else. Theodore de Mayerne left detailed medical notes on his patient which record, for example, that the King ‘often swells out with wind’ and suffered from legs ‘not strong enough to sustain the weight of the body’; but the only ‘Beneficial Evacuation’ Mayerne mentions was the King’s almost daily ‘haemorrhoidal flow’, which, if blocked, made him ‘very irascible, melancholy, jaundiced’.15

Williams, too, was puzzled by Harvey’s diagnosis. ‘This symptom of the King’s weakness I never heard from any else,’ he commented, ‘yet I believed it upon so learned a Doctor’s observation.’ He even attempted to deduce his own theory on how the disease developed, suggesting that the ‘ague’ had become ‘Mortal’ because the infection or ‘Spring’ had entered so far that it had been able ‘to make a commotion in the Humours of the Body’ that could no longer be expelled with ‘accustomed vapouration’.16 It would also explain why a hot plaster applied to the King’s stomach might help, for, by provoking sweat, or even blisters, it might encourage ‘vapouration’ of the offending humours and so restore the body to a state of healthy balance.

The effect of Harvey’s testimony to the select committee and to Bishop Williams was to deflate the poisoning case. It did not exonerate the Duke, nor did it reveal the all-important recipe for the medicine; but it strongly suggested that Villiers’ intervention was no more than inconvenient, and that it had been insisted upon by James himself, who was an exasperating patient (one fact upon which nearly everyone seemed to agree). The King, Harvey told the select committee, ‘took divers things’ regardless of his medical team’s advice, on account of his ‘undervaluing physicians’.

In its report to the House of Commons, the select committee concluded that ‘when the King [was] in declination’, the Duke had ‘made [the posset and plaster] be applied and given, whereupon great distempers and evil symptoms appeared, and physicians did after advise Duke to do so no more, which is by us resolved a transcendent presumption of dangerous consequence’. On the basis of this, it resolved that the charges should be annexed to the others levelled against the Duke.

When the report was presented to the House, Sir Richard Weston, Charles’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, led a rearguard action on the King’s behalf to defend the Duke, claiming that there was no evidence of a crime being committed. Despite this intervention, the MPs backed the select committee’s report and added the charge to their list of grievances.

But Charles would not sacrifice Villiers. Days after his submission to the select committee, the King sent the Earl of Arundel to the Tower of London. His pretext was that the Earl had allowed his son to marry a royal ward, but everyone knew it was for supporting the anti-Buckingham faction in the House of Lords. After repeated commands to the Commons to drop the charges, Charles eventually dissolved Parliament, thus bringing the impeachment proceedings to a peremptory close. He still did not have the subsidy he needed, at a time when he was having to pay for a disastrous military adventure launched by Villiers against Spain. Facing bankruptcy, he turned over royal lands to the value of around £350,000 to the City in return for the liquidation of his debts, which amounted to £230,000. He also decided to impose a ‘forced loan’, the menacing term for an interest-free, non-refundable levy extracted from taxpayers, claimed as a royal prerogative at times of national emergency. Charles’s predecessors had used this technique, but the levies had generally been small, few had to pay, and many were let off – William Harvey, for example, had managed to avoid a loan of £6. 13s. 4d. imposed by James I in 1604 when a group of influential friends petitioned on his behalf.17 This time, all rateable taxpayers were expected to contribute, and five separate payments were demanded. A series of high-profile protests resulted. Seventy-six members of the gentry were imprisoned and several peers were dismissed from their offices for refusing to pay. Pondering on the ancient common-law principle of habeas corpus, judges considered whether the royal prerogative extended to imprisoning without charge individuals who represented no threat to national safety; but they could not bring themselves to rule definitively on such a sensitive matter.

The poisoning charges against Villiers were lost in the midst of these epic struggles, and became irrelevant when John Felton, a naval lieutenant, stabbed the Duke to death at Portsmouth in 1628. As to the truth of the charges, they were widely believed at the time, and historians have debated the matter ever since, on the basis of evidence that can never be decisive. Villiers was probably capable of hatching such a plot, and Charles, who had suffered many humiliations at the hands of his father and who was impatient to take the reins of government, may even have connived. But James was already ill before the Duke’s interventions. In addition to malaria, he was suffering from a variety of chronic ailments, including gout and possibly the royal malady porphyria (the ‘madness’ of King George III, a non-fatal but debilitating intermittent disease that got its name from the Greek for purple, the colour of the sufferer’s urine). Poisoning is one possible reason why a condition originally considered to be non-threatening turned lethal, but there are plenty of others.

No censures were brought against the physicians. They could have been accused of negligence, but the committee was only interested in attacking Villiers and seemed to accept the difficulties of managing a royal patient. However, the episode left a mark on their profession, barely noticeable in the mid-1620s but soon to become as obvious to its enemies as the most unsightly wart. In 1624, an Oxford scholar called John Gee had published The Foot out of the Snare, a list of all Catholics known or suspected of living in London. In addition to naming priests and ‘Jesuits’, it had a section devoted entirely to ‘Popish Physicians now practising about London’. Dr Moore was the first to be listed, but there were many others, including Thomas Cadyman, Robert Fludd, John Giffard, and Francis Prujean, all of them prominent members of the College. Many had, Gee pointed out, been to ‘Popish Universities beyond the seas’ such as Padua, ‘and it is vehemently suspected that some of these have a private faculty and power from the See of Rome’ to administer the last rites to their patients. Harvey was not among those listed, and never would be. Though disliking Puritans, he steered clear of religious controversy. Protestants in Parliament, however, demanded, in 1626 and again in 1628, that the College identify any practising physicians who were ‘recusant’ (Catholics who refused to attend Anglican services). Lists were duly drawn up that identified Moore and Cadyman among others. No action was taken against them, either by Parliament or by the College. Many, in particular Prujean, went on to prosper; but the poisoning episode served to reinforce further the feeling among some Protestant radicals that the College had the same papist leanings and corrupt attitudes as the court it served.18

William Harvey came out best from the whole controversy. Within a few weeks of the select committee inquiry drawing to a close he received a ‘free gift’ of £100 from Charles I ‘for his pains and attendance about the person of his Majesty’s late dear father, of happy memory, in time of his sickness’. There is also a reference among the College’s papers to Harvey receiving a ‘general pardon’ from Charles in early 1627, at the time when the parliamentary impeachment of Villiers was launched. The pardon appears to have been designed to provide retrospective immunity from any charges relating to Harvey’s time as one of James’s physicians. Such immunity was not routinely provided to royal physicians, so the fact that it was granted suggests a specific charge was anticipated – for example that Harvey was somehow complicit in James’s death.19 Whatever the significance of the new king’s generosity, it confirmed Harvey’s special position at Charles’s side, where he would remain the most loyal and devoted of royal servants, unshakeable in his attachment to the King during one of the roughest reigns in English history.

A visitation of plague to London as depicted in Thomas Dekker’s A Rod for Run-Aways, 1625.

In the summer months of 1625, while Parliament and the court were at Oxford debating Buckingham’s impeachment, the scholar and poet John Taylor chaperoned Queen Henrietta Maria, just arrived from France, on a trip up the Thames from Hampton Court to Oxford. Gliding on the royal barge through the lush countryside, past Runnymede, where the Magna Carta was signed, and the towers of Windsor Castle, the royal party found the gentle pleasures of a summer cruise transformed into a ‘miserable & cold entertainment’. Crowds of starving, homeless people lined the banks. They were Londoners, desperately trying to escape one of the deadliest outbreaks of the plague in the city’s history – at least as severe as the more famous Great Plague of 1665. Having reached the country, these refugees had faced what Taylor described as a ‘bitter wormwood welcome’ from the country folk. Greeted as wealthy tourists in better times, they were shunned for fear that they carried the contagion. ‘For a man to say that he came from Hell would yield him better welcome without money, than one would give to his own father and mother that come from London,’ Taylor observed.20

Back in London, a stray visitor would not at first have beheld the apocalypse, just empty streets deodorized with oak and juniper smoke, musket fumes, rosemary garlands and frankincense, and peals of bells. They would pass dormant houses, the staring eyes of their inhabitants glimpsed through windows thrown open to let in the fragranced air and the clarions. They would spot stray dogs who had lost their masters, ditches left undredged for fear of stirring up pestilential airs, lone pedestrians chewing angelica or gentian or wearing arsenic amulets to ward off infection, some coming to a sudden halt and holding out their arms in curious positions, as though carrying invisible pails of water – signs of the first twinges of the characteristic plague sores or ‘buboes’ that appear under the arms.21

‘The walks in [St] Paul’s are empty,’ observed Thomas Dekker, who having written about the last plague outbreak in 1603 found his fascination revived along with the contagion. Not a ‘rapier or feather [was] worn in London’. The rich were gone, the rest unable to bear the inflating cost of a ticket out. ‘Coachmen ride a cock-horse,’ Dekker wrote, ‘and are so full of jadish tricks, that you cannot be jolted six miles from London [for] under thirty or forty shillings.’ Shops were shut, businesses closed, ‘few woollen drapers sell any cloth, but every churchyard is every day full of linen-drapers’. Cheapside, London’s main market, was empty, ‘a comfortable Garden, where all Physic Herbs grow’.22

Physic herbs may have been plentiful, but not physicians. More Fellows of the College were in attendance to minister to James I during his final illness than in all of London during that deadly spring and summer of 1625. On 21 April, less than a month after the royal medical retinue had returned to the capital, the entire membership of the College was summoned to Amen Corner to undertake a solemn selection procedure to decide who should remain in the capital to deal with the epidemic. They filed into the Comitia room one by one and, before the President, Dr Atkins, named those they thought should stay to represent the College. The names that emerged were Sir William Paddy, John Argent (an ‘Elect’ or senior member of the College and soon to become its president), Simeon Foxe (another future president), and William Harvey. All the others were relieved of their collegiate duties, and most presumably fled.

The official College line for dealing with the plague was set out in a treatise entitled Certaine Rules, Directions, or Advertisements for this Time of Pestilential Contagion, first published in 1603 at the time of the last ‘visitation’, and reissued to deal with the current one. Written by Francis Herring, a College Elect, and dedicated to the King, its first words defined the plague in terms of a Latin dictum taken from the Bible, which translated as: ‘The stroke of God’s wrath for the sins of mankind’. This view of plague as a punishment, in particular for pride, was backed up by ministers like William Attersoll, who pointed out that God sent the first plague to strike the Israelites for ‘rebelliously contending against the high Priest, and the chiefest Magistrate to whom God committed the oversight of all’. ‘This is not only the opinion of Divines,’ Herring continued, ‘but of all learned Physicians … Therefore his [the physician’s] appropriate and special Antidote is Seria paenitentia, & conversio ad Deum: unfeigned and hearty repentance, and conversion to God.’23

The doctors did have some medical advice to offer. ‘Eschew all perturbations of the mind, especially anger and fear’ Herring wrote. ‘Let your exercise be moderate … an hour before dinner or supper, not in the heat of the day, or when the stomach is full. Use seldom familiarity with Venus, for she enfeebleth the body.’ As for remedies, they were various, in particular ‘theriacs’ or treacles of the sort used to treat James in his final illness. Herring did not provide recipes for these – it would break the College statutes to do so, and in any case he expected those educated and rich enough to read his treatise to consult a physician. However, he did provide a set of basic remedies for treating those too poor to afford medical fees. The aim of these was to produce beneficial sweating at various intervals in the illness’s development. They could be made at home and included ingredients that were relatively easy to get hold of, such as radish, caraway seeds, and ‘middle or six-shilling beer’.

Herring also provided advice to the city authorities, in particular relating to the matter of hygiene in public spaces. The College had a low opinion of urban health standards, noting the multitude of ‘annoyances’ that had been allowed to develop and which now aided the epidemic’s spread. Rampant development had produced overcrowding, ‘by which means the air is much offended and provision is made more scarce which are the two prime means of begetting or increasing the plague’; there was ‘neglect of cleansing of Common Sewers and town ditches and the permitting of standing ponds in diverse Inns which are very offensive to the near inhabiting neighbours’. More offensive still were the ‘laystalls’ or dumping and burial grounds accumulating beyond the city’s northern limit. Over the city wall at Bishopsgate or Moorgate lay an unsavoury landscape of fens, shacks, kilns, compost heaps, plantations, ruined abbeys, rubbish piles, firing ranges, laundries, dog houses, and pig stalls. This was the world of Bedlam, the famous hospital for mental patients, and the Finsbury windmills, built atop a vast heap of human remains excavated from a charnel house next to Amen Corner. This would also become the setting for Nicholas Culpeper’s practice, and where he and his comrades would muster for the future fight against the sovereign the physicians now served. As far as the physicians were concerned, the whole area was the brewery of infection. From this wasteland the ‘South Sun’ drew ‘ill vapours cross the City’, polluting the north wind, ‘which should be the best cleanser and purifier of the City’. It was upon these dumps of ‘well rotted’ waste that the city gardens were gorged, ‘making thereby our cabbages and many of our herbs unwholesome’.24

In response to such complaints, the authorities drew up a series of emergency ‘Orders to be used in the time of the infection of the plague within the City and Liberties of London’. The aim was to deal with the situation ‘till further charitable provision may be had for places of receipt for the visited with infection’ – in other words, in anticipation of an evacuation of plague victims to surrounding pest hospitals, a monumental undertaking which the authorities were not prepared to pay for out of city funds. The orders focused primarily on identifying sites of infection and sealing them off. Any house or shop in which a resident had died of, or become infected with, the plague was to be shut up for twenty-eight days, and over the door ‘in a place notorious and plain for them that pass to see it, the Clerk or sexton of the parish shall cause to be set on Paper printed with these words: “Lord have mercy upon us”, in such large form as shall be appointed’. One person appointed by official parish ‘surveyors’ would be allowed out to ‘go abroad’ to buy provisions for the incarcerated residents, at all times carrying ‘in their hand openly upright in the plainest manner to be seen, one red wand of the length iii foot … without carrying it closely, or covering any part of it with their cloak or garment, or otherwise’. They were further required to always walk next to the gutter, ‘shunning as much as may be, the meeting and usual way of other people’. Those who failed to do this faced eight days locked up in a cage set beside their home.

As to the ‘annoyances’ pointed out by the physicians, the orders called for the streets to be cleaned daily by the parish Scavenger and Raker, for dunghills to be cleared, for pavements to be mended ‘where any holes be wherein any water or filth may stand to increase corruption’, and for the owners of pumps and wells to draw each night between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. at least ten pails of water to sluice out the street gutters. On the matter of treating the sick, the orders were much less specific. They simply mentioned that a ‘treaty’ should be agreed with the College ‘that some certain and convenient number of physicians and surgeons be appointed and notified to attend for the counsel and cure of persons infected’.25

The Mayor and Aldermen published a further set of orders, hard to date, but probably in the summer of 1625. These show that the College was no longer involved in the city’s increasingly desperate measures to control the crisis. Only surgeons are mentioned, six to accompany the searchers and identify cases of plague, there having been ‘heretofore great abuse in misreporting the diseases, to the further spreading of the infection’. These new orders were more draconian than the previous ones. The surgeons were offered 12d. per body examined, ‘to be paid out of the goods of the party searched, if he be able, or otherwise by the parish’. Infected properties were to be identified, not just with a sign, but with a large red cross painted in the middle of the front door – the first appearance of what became the universal mark of contamination. No longer were appointed residents allowed out to buy necessities. Instead, everyone was to be confined indoors for a month, with a day- and a night-watchman to stand guard and fetch provisions as required, locking up the house and taking the key while away from his post.26

The physicians were left out of these orders because they had fallen out with the city authorities. This is confirmed by a meeting held at the College in 1630 to discuss a less serious outbreak, during which Harvey pointed out that there was no point in selecting a team of practitioners to advise and help city officials because during 1625 he and his colleagues had been ignored. The exact cause of the dispute is unknown, but the very fact that it had come at a time of such intense medical need shows that, on the streets at least, the physicians had become an irrelevance. Those who had disappeared became resentfully numbered among the rich ‘runaways’ attacked by Dekker, so much so that when they returned many stopped wearing their official robes in public to prevent being identified, despite reprimands from the College President. Harvey and the three lone colleagues who remained presumably treated their own patients, but they had no documented involvement in dealing with the escalating number of cases that arose among the mass of the population, which produced 593 deaths in the first week of July, 1,004 in the second, 1,819 in the third, 2,471 in the fourth, peaking at 4,463 in the third week of August.27 Throughout these desperate months, Amen Corner remained empty, the Censors inactive. The only meeting to be called was convened at the house of the President, Dr Atkins, to appoint his successor.

The inaction of the doctors left the market for medicine wide open, and the apothecaries, no longer mere Grocers but now enjoying the dignity of a Society of their own, stepped into the gaping breach. As the number of cases mounted, it was they who visited the sick and distributed the medicine. They began mass-producing Theriaca Andromache, Mithridate, and London Treacle, the physicians’ favourite antidotes. One particularly industrious apothecary managed to produce 160 lb of Mithridate in one month, enough for 15,360 doses.28 These medicines included an enormous number of ingredients: animal derivatives such as deer antler and viper flesh, spices such as nutmeg and saffron, flowers such as roses and marigolds, herbs such as dittany and St John’s wort, anodynes such as opium and Malaga wine. By June, supplies of some key ingredients had run out. As required by its charter, the Society of Apothecaries consulted Harvey and his three colleagues, as the College’s official representatives, on the use of substitutes. At other times, the College insisted on the recipes in the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis being rigidly followed, but on this occasion no resistance was offered.29

The physicians had in any case tacitly accepted that the apothecaries were in charge, as they had apparently let them prescribe as well as dispense medicines on a routine basis, breaking the cardinal rule of the College’s as well as the Society’s charter. It was impractical for a handful of physicians to write bills for the thousands of patients clamouring for medical help. In Harvey’s tiny parish of St Martin’s in Ludgate, one of the worst affected, there were over 250 deaths and an unrecorded number of infections, among a population unlikely to have been much more than a thousand.30 No lone physician could be expected to cope with such levels of sickness, even if the victims were able to afford his fees.

The most obvious sign that the physicians had relinquished responsibility for dealing with the plague came in early 1626, when it had passed its height. Harvey had once more been elected a Censor, and at a meeting he attended in 1626 one John Antony appeared accused of having practised without a licence for over two years. A month later Antony returned with 8 lb of a medicine he was prescribing ‘which he handed over to the President and asked that he might be allowed to practise and connived at: which was granted to him by those present’ – an unprecedented display of tolerance.31

Nehemiah Wallington the wood turner had a small shop in Little Eastcheap, between Pudding Lane and Fish Street Hill. Standing upon the doorstep in early 1625, he surveyed ‘this doleful city’, listened to the ‘bells tolling and ringing out continually’, and wondered what would become of him and his family.32

If the courtiers, the physicians, the rich merchants with royal monopolies, the ‘great Masters of Riches’, as Dekker called them, were the runaways, Wallington was typical of those left behind.33 Figures are imprecise, but by the 1620s crafts- and tradesmen like him made up the bulk of London’s householders.34 Their standard of living was modest, and for some barely distinguishable from poverty in bad years; but they had something few of their sort enjoyed outside London – political influence. The City could not be called democratic, but it was closer to that ideal than most other institutions of the era. Wallington and his ‘middling sort’ were ‘freemen’, citizens, with a say in the running of their livery companies (the Turners, in Wallington’s case). These companies in turn not only ran London’s government, but were bankrolling the debts James, and now Charles, had run up in their attempts to avoid having to go cap-in-hand to Parliament.

Nehemiah’s neighbourhood. Little Eastcheap is the lane at the top of the map, here identified as ‘St Margarets patens’.

Nehemiah Wallington shared another feature common to many Londoners of his class: he was a Puritan, and an avid reader of the Bible and biblical exegeses, such as William Attersoll’s analysis of the Book of Numbers. But where Attersoll’s rural congregation rejected theological innovation, that to which Wallington belonged thrived on it. They lapped up lectures on predestination, the role of Church government and the meaning of divine election.

Wallington also believed in divine providence – that events on earth somehow expressed God’s will. From the moment he ‘came forth polluted into this wicked world’ in 1598, every event, from the tiniest domestic incident to the greatest international affairs, was to be investigated to see how it fitted in with God’s plan. Most Puritans understood events in this way, but Wallington took it a step further: he wrote all his deliberations down, creating a journal of human struggle amounting to over two and a half thousand pages.

The plague of 1625 represented one of the first major episodes to be examined by Wallington in this way, and his account of it provides a vivid street-level view of what it was like for the ordinary citizens of London left behind and how they dealt with it – not just medically, but philosophically and emotionally.

Like the College of Physicians, Wallington assumed that the plague must have been sent by God. But where the College, taking its line from the religious establishment, saw it as a ‘general humiliation of the people’, Wallington believed it was a sign of how ‘idolatry crept in by little and little’ and how ‘cunningly and craftily hath the enemies of God’s free grace brought in superstition’.35 In other words, it was a divine reaction to the established Church of England being drawn dangerously back towards the idolatrous rites and doctrinaire attitudes of Catholicism. Charles I had already revealed himself to be an enemy of Puritan reform, having chosen the controversial religious conservative Robert Montagu as his theological adviser. In a book ostentatiously dedicated to Charles that appeared in 1625, Montagu had attacked ‘those Classical Puritans who were wont to pass all their Strange Determinations, Sabbatarian Paradoxes, and Apocalyptical Frenzies under the Name and Covert of the True Professors of Protestant Doctrine’.36 Puritans such as Nehemiah Wallington would have found it hard not to see the distorted reflection of themselves in Montagu’s caricature and to conclude that their beliefs were under threat.

Thus the plague could not have descended on London at a more significant or sensitive time: it was part of the unfolding struggle between the Puritan saints and the courtly sinners. Wallington had already noted, a few years before, a ‘poor man of Buckinghamshire, that went all in black clothes, with his hat commonly under his arm’ and who for the space of a year stood before the palace gates at Whitehall calling to the King ‘for woe and vengeance on all Papists’. ‘I myself have seen and heard him,’ Wallington wrote, ‘crying, Woe to London, woe to the inhabitants of London.’37

Woe indeed. In the summer months of 1625, the tolling of the bells was ceaseless, and ‘could not but make us wonder at the hand of God to be so hot round about us’. Would even Nehemiah’s godly family be touched? He certainly did not regard himself as immune. He was a sinner too, all his efforts at saintliness, set out in a list of seventy-seven articles drawn up on his twenty-first birthday, proving paltry in the face of temptation. ‘I have many sorrows and am weak,’ he admitted to his journal.38

Through the summer weeks of 1625, all he could do was study the Bills of Mortality nailed to the door of his local church, St Margaret’s in New Fish Street: 5,205 dead in August, 43,265 in the year up to 27 October. He heard gossip about whole families – fifteen or sixteen in a single household – being wiped out, or perhaps leaving a lone survivor to endure a life of isolation, ‘a torment which is not threatened in hell itself, as the poet and preacher John Donne observed at the time.39