Читать книгу Yellow River Odyssey - Bill Porter - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCITY OF SPRINGS

From the Yellow River Delta, I returned to the main highway near the ancient site of Lintzu and flagged down the next bus headed for Chinan, the capital of Shantung. If it had been fall, I might have stopped in Tzupo. Every fall the north wind blew away the polluted air from the city’s petrochemical plants long enough for kite aficionados to test their creations and skill at China’s biggest kite festival. But it was the end of March and too cold for kites. In fact, I arrived in Chinan in what the bus driver said was the biggest snowstorm of the winter, and my feet were frozen.

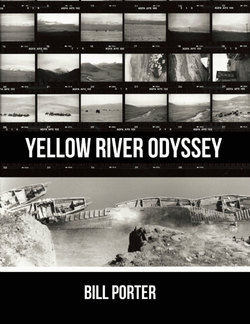

The moat and old city wall of Chinan

The English-language travel guides that I had looked at dismissed Chinan as not worth visiting. But snow covered its blemishes, and the city looked quite lovely in black and white. After checking into the old Chinan Hotel, I spent the afternoon sipping hot tea beside my open window, watching the snow fall and warming my frozen feet against the radiator. By the next morning, my feet were ready to walk again, and they took me to see the sights. Chinan was known as the City of Springs – until recently there were seventy-two of them, and I trudged through the snow and slush to see the most famous of them all. It was called Paotu Chuan, or Ever-Gushing Spring, and it was just inside the southwest corner of the old city wall. The spring was in the middle of a pond, and the pond was in the middle of a park. But the spring was dry, and water was being pumped in from somewhere else to fill the pond. A man who was sweeping snow from the path near the spring said the excavation and construction of building foundations nearby had stopped the flow, and the same thing had happened to most of the city’s other springs. Efforts to reestablish their flow had failed, and Chinan was the City of Springs in name only.

I sighed a sigh I’m sure was sighed by the city’s own citizens and entered a memorial hall just beyond the spring. It was built in honor of China’s most famous poetess, Li Ch’ing-chao. That part of town was where she lived in the eleventh century, both with and without her husband. She was married to a scholar-official. But when the nomadic Jurchens invaded North China and sacked the Sung dynasty capital of Kaifeng 300 kilometers southwest of Chinan, her husband, being an official, fled south with the government. And since it was not customary for officials to take their families with them on such distant assignments, Li Ch’ing-chao stayed in Chinan and wrote poems:

Year after year I’ve gazed into my mirror

rouge and skin creams only depress me

one more year he hasn’t returned

my body shakes when a letter arrives

I can’t drink wine since he left

autumn I consume my tears instead

my thoughts vanish into distant mists

the Gate of Heaven is far closer

than my beloved south of the Yangtze.

Her husband served as magistrate of Nanching, not far upriver from where the Yangtze made its last bend and headed for Shanghai and the East China Sea. But not long afterwards, her husband died, leaving her grief-stricken:

Evenings find me with uncombed hair

I have a comb and a mirror

but now that my husband is gone

why should I waste my time

I try to sing but choke on my tears

I try to dream but my boat of flowers

can’t bear the weight of such sorrow.

Thinking I might translate the weight of such sorrow into English, I bought a book that included a commentary along with her poems. Then I walked back outside the hall and through the park and past the old city wall. Although most of Chinan’s springs had dried up, there was still plenty of water in the moat outside the wall, and I followed its snow-covered banks to Taminghu Lake. The lake was just inside the northern part of the wall. Near the entrance, I stopped to look at a huge stone on which someone had carved the golden calligraphy of Chairman Mao. My calligraphy teacher once described Mao’s style as “all guts and no bones.” I was never very good at calligraphy. I also had trouble with the bones.

Just past the calligraphy was the lake. I was surprised how big it was and how deserted. Then again, why would anyone want to visit a lake when the weather was so cold? There were still snowflakes in the air. The only other person there was a man who rented boats. Since I was also there, I decided I might as well go out on the water and row around. I rowed out to a small island and visited its lone pavilion. It was called Lihsia Pavilion, and it was immortalized after the poet Tu Fu and the calligrapher Li Yung spent a night there getting drunk in the year 745. The inscription that recorded what they wrote that night was too faint to read, and I was losing feeling in my feet again. I rowed back to the shore and walked out to the road and flagged down a taxi. I asked the driver to take me to the north edge of town to the bridge of barges that carried cars and buses and trucks across the Yellow River.

The bridge of barges was a jury-rigged affair that rocked back and forth every time a vehicle crossed. Pedestrians had to hold onto a chain that separated them from the traffic and that also kept them from falling into the river. I walked out and tried to take a photo, but I couldn’t let go of the chain long enough. In winter, the river shrank to the point where a person could throw a rock across. In fact, this was the narrowest section of the river on the entire floodplain. Even in summer, when the water level was at its highest, it was only 200 meters across in Chinan, which was the distance between the huge stone dikes on either side. According to a man who worked near the bridge, the bottom of the river was actually five meters higher than the city due to the constant deposit of silt – and that was just the bottom of the river, not the top of the river. He said every July an army of volunteers had to pile sandbags along the dikes and work around the clock to keep China’s city of springs from becoming a city of mud.