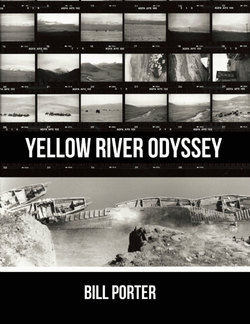

Читать книгу Yellow River Odyssey - Bill Porter - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSHANGHAI

I asked the concierge to unlock the window so I could smell the city. I was on my way from Hong Kong to follow the Yellow River from its mouth to its source and couldn’t resist the temptation to stop in Shanghai for the China Coast Ball. This annual bacchanal was organized by and for the Hong Kong expatriate community, and it was normally held in March at the Belle Vista in Macao. But in 1991 the Belle Vista was being renovated, and the organizers turned to the Peace Hotel in Shanghai as a suitable replacement. The Peace had been boarded up during the Cultural Revolution, and the splendor of its art-deco interior had survived intact.

From the airport, I took a taxi to the Peace, but the Peace was full, as were the other hotels opposite the river promenade known as the Bund. The ball’s organizers were expecting over 500 members to show up and had reserved all available rooms six months in advance. Revelers were coming from as far away as Europe and Australia. Fortunately, a few blocks away, the former Russian consulate-general’s residence had reopened the week before as the Seagull Hotel, and I had my choice of accommodations. The place still reeked of glue from the newly paneled hallways, so I sought relief in the lesser evil of the Huangpu River. And the concierge was kind enough to unlock my room’s window. The river flowed past the Seagull and the other hotels on the Bund, and twenty kilometers to the north it joined the waters of the Yangtze and the East China Sea. It was the junction of these waterways that was the reason for the city’s existence. Most of China’s billion citizens lived in the Yangtze watershed, and Shanghai connected them with the rest of the world. That didn’t mean much until a few centuries ago, but the city had made up for lost time. I thanked the concierge and looked out onto the Bund.

China Coast Ball at the Peace Hotel

In Samuel Couling’s 1917 account of Shanghai in the Encyclopaedia Sinica, he wrote, “The whole district is a mud-flat with no natural beauty, and art has done little to improve matters, except in a few of the buildings on the Bund.” The city had changed, but I wasn’t there to see the changes. I was there for the ball, and the ball was still a few hours away. So I went for a walk. From the Seagull, I walked north through what was once the American spoils of the Opium Wars. It began raining, but my parka kept me dry enough. A few blocks later, I entered Hungkou Park and stopped to pay my respects at Lu Hsun’s grave.

Lu Hsun was China’s greatest twentieth-century writer, and Shanghai was where he spent the last decade of his life, until his death in 1936 at the age of fifty-five. His bronze statue sat near his tomb in a bronze wicker chair. It was remarkable for its simplicity. I bought some flowers from a vendor and laid them next to a wreath left by a group of Japanese. To avoid arrest in China for his anti-imperial writings, Lu Hsun fled to Japan and stayed there until the Chinese Revolution succeeded in toppling the Ch’ing dynasty in 1911. Despite his socialist leanings, he was, and still is, viewed as a hero in Japan. The park also included the Lu Hsun Museum, where it seemed everything he ever owned was on display: his pocket watch, his umbrella and, of course, his books and journals. There was a collection of woodblock prints he made early in his career that revealed better than words his sympathy for the sufferings endured by his fellow Chinese. They reminded me of the work of Kathe Kollwitz. I looked at his death mask and thought about the changes in China since he last closed his eyes.

From the park, I continued walking north and stopped several times to ask directions. I finally found the lane I was looking for and then the plaque for Lu Hsun’s home. The two-story brick house was normally open to the public, but it was closed that day. A man across the lane saw me and said the caretaker kept the place closed whenever it rained in order to keep people from tracking mud inside. The man’s name was Li Hou. He said he was an artist, and he invited me to join him for a cup of tea. While I sat in an armchair in his living room, he showed me his paintings, unrolling them one by one on the room’s cement floor. The long paper scrolls of black ink and colored washes made me think Lu Hsun had simply packed up and moved across the lane and exchanged the realism of youth for the abstraction of old age.

I would have stayed longer, but I didn’t have time to linger. I thanked my host and headed back to the hotel. By the time I got back, it was dark. I looked outside my window again at the Bund. All the buildings were lit up. “Bund” was a Hindi word for a river embankment or promenade. The English picked up the word when they colonized India. And they brought the word with them to Shanghai along with opium. And that night their descendents had paid the city US$5,000 to turn on the lights normally reserved for special holidays, such as Lunar New Year and National Day.

In the distance, I could see taxis pulling up to the Peace Hotel and partygoers getting out. I walked down and crossed the bridge that spanned Suchou Creek and joined them. I entered the hotel’s revolving door along with several couples. And as we did so, we were greeted by a gauntlet of young Chinese girls wearing white ballet tutus and waving bouquets. We walked past them and waved back and crowded into an elevator. Eight floors later, we were swept into the ballroom. At the door, the maitre d’ was collecting invitations, and I didn’t have one. And my purple parka did not exactly match the formal attire of the other guests. He motioned me aside. But I was prepared. I had a camera hanging from my neck, and I showed him my Hong Kong journalist ID. It was for Metro News, the English-language radio station where I worked. It didn’t occur to the man that radio journalists didn’t use cameras. But he waved me in anyway, and I joined a throng of more than 500 gowned and tuxedoed expatriates who were there to party. Just in case someone was looking, I took a few photos. But mostly I danced.

The music was supplied by the Peace Hotel’s Old Time Jazz Band, whose members were in their seventies and eighties. They had managed to survive the Cultural Revolution, and they could still play the “Chatanooga Choo-choo.” Fortunately, their age soon caught up with them, and they were replaced by a Chinese rock-and-roll band that blew out two sets of speakers playing Jimi Hendrix. The party lasted all night, and at noon the next day I boarded a coastal steamer heading north.

The Bund, Shanghai