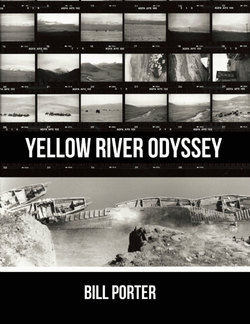

Читать книгу Yellow River Odyssey - Bill Porter - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTAISHAN

From Lingyen’s forest of stupas, we returned to the main highway and continued south to T’ai-an. T’ai-an was the name of the town that had grown up around the temple where emperors came to pay their respects to Taishan. Mountains played an important role in Chinese culture. They were like acupuncture points on the body of the earth and home to powerful forces. And Taishan was their soul. It was where the recently departed spirits of the dead came for assignment to the afterlife. It was the earthly conduit to the netherworld, and the mountain was the single biggest center of pilgrimage in China. Emperors, too, came there to make peace, not only with the hereafter, but also with the forces of the present, whose assistance they needed in this life. I arrived too late in the day to follow them up the trail to the summit and contented myself with going to bed early. But the next morning I was ready to join the pilgrims. After checking out and storing my bag at the train station, I took a local bus to the temple at the foot of the mountain and stopped just outside the main gate at the pavilion where emperors dismounted to perform a simple ceremony announcing their arrival in the land of spirits. I followed them through the main gate and past five huge cedars planted by Emperor Wu in 110 BC and entered the huge shrine hall where emperors performed the main ceremony.

The Diamond Sutra carved into a rock face

In ancient times, imperial visitors conducted their ceremonies to the mountain at three temples: one at the foot of Taishan; one halfway up; and a third at the summit. Of the three, only the one at the foot of the mountain had survived. It was one of the biggest shrine halls in China: forty-eight meters wide, twenty meters deep, and twenty-two meters high. Only the Confucian Temple in nearby Chufu and the Imperial Palace in the Forbidden City were bigger.

The hall was built in 1009 at the beginning of the Sung dynasty, or nearly fifty years before William the Conqueror invaded Britain. And it was still there nearly a thousand years later. Its walls were national treasures. They were covered with thousand-year-old murals depicting an imperial visit complete with officials, attendants, ancestors and a pantheon of heavenly deities. The murals were among the great treasures of Chinese art, on a par with those of Michelangelo, only they were painted 500 years earlier than Michelangelo’s. I tried to consider the enormity of the work: three and a half meters high, sixty-two meters long, a thousand years old. Taishan definitely received its share of respect.

According to Chinese mythology, the world was created by a creature named P’an-ku, who spent 18,000 years chiseling out the space between Heaven and Earth where humans have been living ever since. When he was done, P’an-ku lay down and died, and his feet became the Western Sacred Mountain of Huashan, his belly became the Central Sacred Mountain of Sungshan, his arms became the Northern and Southern mountains of Hengshan and Hengshan (same sound, different characters), and his head became the Eastern Sacred Mountain of Taishan. Thus, Taishan had been venerated as one of China’s five sacred mountains since pre-historic times. But 2,000 years ago, just as humans revere their heads more than their hands and feet, Taishan was elevated above the other sacred mountains. This happened in the Han dynasty.

The Han was one of the most glorious dynasties of Chinese history, and the reign of Emperor Wu was the dynasty’s most glorious period. In addition to his military and political accomplishments, Emperor Wu was known for his devotion to Taoist regimens that promised immortality. Acting on the instructions of his Taoist advisers, Emperor Wu conducted the most splendid and important religious ceremony of his entire reign at the foot of Taishan for the purpose of establishing harmony among the various spiritual forces whose assistance he required.

A thousand years later, during the Sung dynasty, the emperor who built the shrine hall that still stood at the foot of the mountain and whose visit was depicted on its walls raised the mountain’s status to that of a divinity on a par with the emperor himself. It was about that time that the story began to circulate that Taishan’s wife also lived on the mountain. Her name was Pihsia Yuanchun, the Primordial Princess of Rainbow Clouds. Over the past thousand years, Taishan and his rainbow-hued cloud bride had become two of the most venerated figures in the entire Taoist pantheon, and shrine halls in their honor could be found in cities throughout China. They were also said to appear from time to time on the trail to the summit, which began just behind the temple where Emperor Wu once drained his treasury to honor their mountain abode.

Leaving the shrine hall, I proceeded up the same path emperors also followed on their way up the mountain. After a few hundred meters, I passed through a great stone archway, and the road turned into a trail of stone steps paid for by emperors and worn smooth by countless pilgrims. People didn’t climb Taishan to get away from others. On an average day a thousand pilgrims hiked to the summit.

Not long after I began my own climb, I passed a stone slab proclaiming Taishan as China’s No. 1 Mountain. Beside it was another, smaller archway. Carved across the top were the words: “K’ung-tzu-teng-lin-chih-ch’u: Confucius climbed here.” Confucius lived seventy kilometers away, and he came there on a number of occasions to pay his respects to the mountain and to seek inspiration in its solitude – but obviously, not near the main trail. Mencius, the most famous among his later disciples, wrote: “Climbing the Eastern Sacred Mountain, Confucius found the surrounding state of Lu tiny. Reaching Taishan’s peak, the Great Sage found the Middle Kingdom small.” Mountains put the rest of the world into perspective. Walking through the archway, I didn’t pause. The peak was still five hours away.

Just beyond the archway announcing Confucius’ visit to Taishan 2,500 years earlier, there was an incinerator where pilgrims sent paper money drawn on the Bank of Hell to their loved ones. In addition to paper money, hawkers sold incense, and the trail was lined with wayside shrines from which clouds of smoke poured forth. I stepped into one such shrine to watch a new deity being fashioned out of straw and mud. The Taoist priest in charge said he hoped to have it ready in time for the pilgrimage season, which began in early April.

A few minutes later, I stopped at another shrine. This one was larger and it had a name: Toumu Temple. Tou-mu was the Goddess of the Big Dipper, and she was in charge of making sure people lived out their allotted span of years. Being the home of spirits waiting for re-assignment, Taishan was where the bereaved came to pray for a good afterlife for their departed loved ones. And while they were making the effort, many of them stopped to ask Tou-mu for a few extra years for themselves. A stele outside the gate explained:

A man makes a name chop for the author’s son.

“Whom Heaven wishes to lift up, no person can cast down. The ups and downs of life are matters that can be ascertained, but not by human power. It is I who can see their source.” Everyone wanted to be on good terms with Tou-mu. But when I went inside her shrine hall, she was gone. She had been replaced by Kuan-yin, the Buddhist Goddess of Compassion. Apparently, even the gods were not able to forestall their own transience.

Musing on this thought, I continued up the trail and came to a sign that pointed away from the main trail to Sutra Rock. I followed a side path through a pine forest and across a stream to a huge rock face on which someone had carved the entire text of the Diamond Sutra. The characters were bigger than my hand, and they were carved there over 1,500 years before I had a hand. The stream I crossed on my way there had once flowed across the rock face and had worn away two-thirds of the sutra’s 3,000 or so characters. There was a small dam above the rock face now, blocking the water from cascading down. But I could still make out the hymn that ended the sutra: “As an illusion, a dewdrop, a bubble/a dream, a cloud, a flash of lightning/view all created things like this.” It was advice even Tou-mu could understand.

Back on the main trail, I came to another rock face. On this one were carved the words “High Mountains and Flowing Water.” These were the names of the two most famous songs for the zither composed by Yu Po-ya three thousand years earlier. Because only Chung Tzu-ch’i could understand what was in Yu Po-ya’s heart when he played them, the two men became the Damon and Pythias of China, representing the truest friendship. But as I continued on, all I could hear was the wind in the pines and the panting of my own breath.

A view of the summit of Mt. Taishan

It took me two and half hours to reach Middle Heaven, which was the halfway point on the trail. Climbing Taishan along with hundreds of pilgrims was not the same as climbing a mountain by myself. I was part of a long line of pilgrims stretching back thousands of years. And since pilgrims needed to eat and drink along the path, at Middle Heaven, there were dozens of stalls set up to accommodate them. I sat down at one next to several pilgrims who were eating something that looked good. I didn’t know what it was, but I ordered some too. It turned out to be hot, spicy tofu pudding. The weather was so cold and my throat so parched, it was ambrosia. I ordered a second bowl, and it was just as good as the first bowl. For those who weren’t able or who didn’t want to walk up the trail, this was where the road from town ended and where a cable car took over. But the cable car was expensive, and most people finished the second half on foot.

After catching my breath and restoring my well-being with the hot tofu pudding, I rejoined the other pilgrims on the trail. From Middle Heaven, the path continued along a long, fairly level stretch of trail that eventually led across Cloud Walk Bridge and then up a flight of steps to Five Pine Pavilion. In 219 BC, China’s first emperor sought shelter there beneath a pair of pine trees during a rainstorm. In gratitude, he made the pine trees ministers in his administration. Originally, there were only two pines. But both were washed away in another rainstorm. And they were replaced by five pines, only three of which remained. Obviously, Taishan was not a good place to be during a rainstorm. But the pavilion built to mark the spot was still called Five Pine Pavilion.

Further on, I paused to catch my breath again and sat down next to a stall where a man was hammering out name

chops on brass rings. He charged 5RMB, or seventy-five cents, and said it would only take five minutes, so I asked him to make one for my son. While I was waiting, an eighty-year-old man I had met earlier waved as he passed by. Gasping between words, he said it was just-a-matter-of-perseverance, one-step-at-a-time. As soon as my son’s name chop was done, I followed him, one step at a time.

Five hours after passing through the archway announcing Confucius’ ascent, I, too, reached the final archway, which was also where the cable car debouched its passengers. On the other side was a gauntlet of trinket sellers and food stalls. It had snowed the day before, and someone had made a snow buddha. I sat down nearby and ordered a bowl of hot cornmeal gruel and some fry bread. I was so famished, once more I had seconds. I was really enjoying being a pilgrim, instead of a lone hiker.

The summit was 1,500 meters high, and in addition to the stalls that supplied pilgrims with sustenance and trinkets, there were a number of shrine halls scattered across the ridge. Chief among them was one dedicated to the mountain spirit’s wife: the Primordial Princess of Rainbow Clouds. As I entered the courtyard, a Taoist priest hurried by on his way to conduct a ceremony inside. I stood outside the hall and watched as a half dozen priests chanted the daily liturgy to the accompaniment of drums and bells and chimes.

From above her shrine, the Yellow River was said to be visible on a clear day, and people often spent the night at one of the hostels near the summit to see the sunrise the next morning. But the lodgings were so flimsy, they reminded me of the big cardboard box that I kept in the garage when I was a boy and that I dragged into the backyard on nights when there was a meteor shower. I took a picture of the snow-covered roofs of the princess’ temple and followed Confucius back down to the civilization he helped establish.