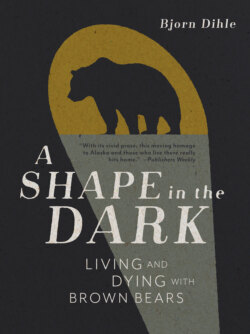

Читать книгу A Shape in the Dark - Bjorn Dihle - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1 The Skin of the Bear

ОглавлениеThis animal is the monarch of the country which he inhabits. The African lion or the tiger of Bengal are not more terrible or fierce. He is the enemy of man and literally thirsts for human blood. So far from shunning, he seldom fails to attack and even to hunt him. The Indians make war upon these ferocious monsters with the same ceremonies as they do upon a tribe of their own species, and, in the recital of their victories, the death of one of them gives the warrior greater renown than the scalp of a human enemy.

—Henry Marie Brackenridge, Views of Louisiana

I first encountered a brown bear when I was four or five years old. It was lying in a salmon stream on Admiralty Island, reduced to bones, pieces of hide, and tendrils of flesh. Thick salmonberry brush and giant trees rose above each bank, offering the illusion of impenetrable walls. A bald eagle glided past and landed on a logjam. Ravens spoke their ancient language from the boughs of Sitka spruce trees. Pink salmon filled the stream and struggled to spawn. Leaving the bear, I waded downstream toward an old cabin my family was staying at. I paused to throw rocks at a belly-up salmon who’d just laid the last of her eggs as she drifted downstream, toward the ocean.

I found my dad and took him back to the carcass, where he cradled his rifle and studied the surrounding salmonberry bushes and jungle. Dad had moved to Alaska from California when he was in his early twenties so he could hunt and experience wilderness. The brown bear has always been a big, mysterious animal to him, something that you have to respect and watch out for. The carcass that lay at our feet wasn’t much bigger than me though. It was likely a two-year-old, the typical age for a cub to be run off by its mother so she could mate again. In the day or two since it had been killed, other bears, eagles, and ravens had reduced it to little more than a skeleton and a tattering of flesh. The stream’s current and the falling rain added to the forces, encouraging blood from flesh and flesh from bone. In the shallows, on the gravel bars, and on the banks nearby were the carcasses of countless decomposing salmon. Even the living salmon, splashing against the current, jockeying for position and digging out redds, were in the process of dying.

I stood beside my dad with little understanding of what was going on. I can’t recall my thoughts, but maybe I suffered a glimmer of awareness. Maybe I imagined a bear crashing through the woods, engulfing me in its jaws, and how even if I escaped its grip, eventually—like the spawning salmon—my blood, flesh, and guts would still be freed of my bones and carried away from the thing I thought was me. We left the carcass, and I followed my dad downstream, staring up at the brush and alders lining the banks, where bear trails led into the unknown.

IN OCTOBER OF 1809, MERIWETHER LEWIS TRAVELED BY HORSEBACK through the Tennessee hills, bound for Washington, DC, to report to President James Madison. Eight years prior, just after taking office, President Thomas Jefferson had handpicked Lewis to be his personal secretary. Jefferson dreamed of building a country that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and he believed that Lewis was the man to set the groundwork to make it a reality. The two became extremely close, their relationship taking on the dynamic of a wise and visionary father grooming his prodigy son for a quest of mythic proportions. Lewis had not only succeeded in leading the Corps of Discovery, also known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, across the continent and back again, making him one of the most famous men in the country, but afterward, Jefferson appointed him governor of the Louisiana Territory—a swath of wild country encompassing more than half of the young United States at the time. Jefferson and the entire nation were waiting eagerly for the young captain to edit and publish his expedition journals and maps, but Lewis seemed unable to focus or articulate what he’d experienced. Time was up though. President Madison had demanded his report, and Lewis could stall no longer.

What, if anything, Lewis saw in the Tennessee forest as he traveled can only be guessed. By all accounts he was drunk, irritable, and lost in a schizophrenic loneliness he couldn’t claw his way out of. Some guessed his poor health was related to his inability to find a wife. He was good-looking, famous, and well-off, although he had money problems. Finding a wife should have been easy—unless, as many historians believe, he was a little off. There’s talk of syphilis or malaria-induced madness, alcoholism and other addictions, not to mention groundless rumors he was gay. There’s no question he was suffering from depression, anxiety, and excessive drinking. No one—at least no one who talked about it in public—really knew Lewis’s inner world.

Lewis tried to kill himself twice en route to Washington—it’s unclear exactly how. His companions disarmed him and placed him under watch. After days of erratic behavior while detoxing, he appeared to return to reason and continued on his journey. The night of October 10, Lewis rode ahead and took a room at Grinder’s Inn on the Natchez Trace Trail. The inn was owned and operated by Priscilla Grinder and her husband, but the latter was away on business. Lewis claimed to have been unable to sleep in a bed since returning from the expedition, so he had his servant spread out a grizzly skin and his buffalo robe on his cabin’s floor.

Perhaps he lay in the thick, wild-smelling fur for a while before his racing thoughts and despair became too much. He took to pacing the room and talking loudly, even yelling, to himself and walking circles around the pelts of the two animals that best symbolize the American West. What was the story behind each animal? Lewis and the expedition had killed so many bison that it was unlikely the robe had any more significance to the captain than warmth and fashion. The bear pelt, on the other hand, was different. For Lewis, no other animal in North America compared to the brown bear. It represented the most mysterious and dangerous elements of the wilderness of the New World. Even the woolly mammoth, which at the beginning of the expedition Jefferson and Lewis had speculated still existed in the North American wild, paled in comparison.

THE BROWN BEAR FIRST MIGRATED FROM ASIA ACROSS THE BERING LAND Bridge to North America around 100,000 years ago. There it met a host of ferocious predators like steppe lions, saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, and—kings over all—giant short-faced bears. With a fourteen-foot arm span, the short-faced bear weighed a ton and on all fours stood eye level with a grown man. Its skull looked like a cross between a bear’s and tiger’s. There are some opinions that the short-faced bear blocked brown bears from migrating south, and whether that’s true or not, little fossil evidence shows brown bears in the contiguous United States until 13,000 years ago, when the short-faced bear and much of the continent’s megafauna appeared to have died at the spears and wit of the Clovis people and environmental factors brought on by climate change.

The Clovis were some of the first people to migrate across Beringia, and their culture evolved to hunt—and survive—the megafauna of America. Their spears had heads between two and nine inches in length attached to wooden shafts and could be thrown, jabbed, and even braced against the ground to impale a charging animal. A spear may not seem like much when faced with the zoological reality of the time, but the Clovis people successfully spread across the continent hunting mammoths, mastodons, giant ground sloths, and a wide array of ungulates. Following along in the fossil record, not long after nearly all the megafauna vanished, the Clovis spearheads disappeared, replaced with weaponry suited for smaller and less fierce animals.

For 13,000 years, the versatile brown bear reigned supreme in the animal world. The bear’s survival was a testament to its intelligence, omnivorous diet, and adaptability, including its ability to go into a torpor during months with low food availability. The brown bear’s range extended from the Arctic Ocean south to northern Mexico and as far east as the Mississippi River. When the first brown bears migrated into northern Southeast Alaska around 12,000 years ago, they encountered an arctic environment as giant glaciers and sea ice melted away, revealing the ABC Islands of modern-day Southeast Alaska. There, it’s theorized that brown bears met and interbred with a vanishing population of polar bears. To this day, the ABC bears’ DNA is more like that of polar bears than other populations of brown bears, including mainland bears that live just four miles away across Stephens Passage, which separates Admiralty Island from the mainland of Southeast Alaska.

The Tlingit people likely arrived in Southeast Alaska not long after the first brown bears migrated into the country. People and bears ate the same food, traveled the same corridors, and lived in the same places. On occasion, they hunted, killed, and ate each other, though for the people, brown bears tended not to be as important a food source as other mammals like deer and seals. No other animal evoked more taboos. A hunt involved elaborate ceremonies and a great amount of respect to the bear to ensure the hunter’s safety and success, and to placate the slain animal’s spirit. The hunting party usually consisted of a small group of men who used dogs, bows and arrows, and spears. They targeted animals three years of age or younger because the meat was more tender and better tasting. Guns and other elements of Euro-American culture would do much to change the dynamic of that relationship, but even in a postcolonial present, many Alaska Natives’ speech and attitude toward bears are instructed by deep ancestral teaching. They recognized that they share many physical and social similarities with bears; many tribes viewed the bear as if it had at one time been human. The bear walks flat-footed like a person; when it stands on its hind legs, it looks like a giant hairy human; a skinned carcass looks similar to a large muscular man. Some still refer to the brown bear in familial terms, calling the animal Grandfather or Grandmother.

The first reference to a European seeing a North American brown bear was in 1602, when the Spaniard Father Antonio de la Ascension, a chaplain and conquistador, reported watching bears feeding on a beached whale in what is now California. The next came in 1691, when Hudson’s Bay Company explorer and trader Henry Kelsey wandered across the Great Plains of Canada by foot and canoe—the horse hadn’t made it that far north yet. Kelsey was the first white person to witness bison and described seeing “silver-tipped” bears, grizzlies whose guard hairs—the long, coarse outer fur on an animal—were silver in coloration. Kelsey reported that two bears traveling together attacked him and a Native—likely either a Cree or an Assiniboine—companion. Despite being armed with only a clumsy flintlock musket, Kelsey killed both bears and earned the nickname Little Giant. When Kelsey killed another grizzly on a different occasion, his Native companions warned him not to keep the hide. “They said it was a god and they should starve,” Kelsey wrote in his journals.

In 1790 Hudson’s Bay writer and explorer Edward Umfreville was the first Euro-American to record an encounter using the name “grizzle bear,” which he coined after the silver coloration of the bear’s fur. A few years later, the explorer and fur trader Alexander Mackenzie wrote of encountering a “grisly bear.” Whether that’s a misspelling or refers to the fear the brown bear inspired is up for debate. Many people, including Theodore Roosevelt, would later argue that the proper spelling and meaning is grisly. During the Corps of Discovery expedition, Meriwether Lewis guessed that the brown, grizzly, grisly, silver, yellow, and white bear were all the same species.

It would take biologists quite a bit longer to come to this same conclusion. In the early 1900s, C. H. Merriam, who headed the Bureau of Biological Survey for twenty-five years and was commonly known as a splitter—a taxonomist who classifies species based on relatively minor characteristics—came up with nearly one hundred different species and subspecies of brown and grizzly bears. Today it’s agreed that all of Merriam’s supposed species of brown and grizzly bears are one and the same: Ursus arctos. That said, physical and social characteristics vary widely, influenced mostly by geography. For instance, a big brown bear on Kodiak Island or the Alaska Peninsula may weigh 1,500 pounds but, due to the abundant availability of food and the close proximity of many other bears, will likely be relatively easygoing. A big brown bear in the taiga of Canada might weigh 500 pounds but, because there is not much food and because a low bear population density means it won’t be as socialized, will have a higher likelihood of being aggressive. In nomenclature Ursus arctos is used to refer to a brown bear that lives within 100 miles of the coast. Grizzly bears, their inland kin, are referred to as Ursus arctos horribilis. They were given this designation in 1815 by the naturalist George Ord, a man whose only experience with grizzlies came from reading Lewis and Clark’s reports.

In 1803, as Meriwether Lewis and the expedition ascended the Missouri River, the young captain frequently referenced the possibility of encountering the “yellow” and “white” bear in his journal. The only bear that Lewis and his men were familiar with was the American black bear. Because the black bear is smaller and more timid than the brown bear, people often have a hard time taking it seriously. Everyone, even the most seasoned guide, deeply respects, and often fears, brown bears.

Lewis wrote in his journal during his first winter at Fort Mandan, on the Missouri River in the center of present-day North Dakota, of their Mandan hosts’ attitude toward the grizzly bear:

The Indians give a very formidable account of the strength and ferocity of this anamal, which they never dare to attack but in parties of six, eight or ten persons; and are even then frequently defeated with the loss of one or more of their party. . . . When the Indians are about to go in quest of the white bear, previous to their departure, they paint themselves and perform all the supersticious rights commonly observed when they are about to make war uppon a neighbouring nation.

The following spring, not long after leaving Fort Mandan, Lewis encountered his first grizzly bears, Ursus arctos horribilis by modern designation—likely either two subadults traveling together or a female with a big cub. He wrote of what transpired:

I walked on shore with one man. about 8 A.M. we fell in with two brown or yellow bear; both of which we wounded; one of them made his escape, the other after my firing on him pursued me seventy or eighty yards, but fortunately had been so badly wounded that he was unable to pursue so closely as to prevent my charging my gun; we again repeated our fir and killed him. it was a male not fully grown, we estimated his weight at 300 lbs.

He went on to offer a rather strange and seemingly inaccurate description of the bear’s testicles being encased in separate scrotum sacks. Every ensuing encounter with brown bears they recorded in their journals told a similar story: men shot bears, and then wounded bears tried to attack terrified men before eventually dying. The amount of lead a bear could take and keep coming both awed and horrified the men. Lewis wrote after a handful of life-or-death encounters, “I find the curiosity of our party is pretty well satisfied with respect to this anamal.”

The most spectacular encounter Lewis had with a grizzly was an anomaly to the rest of the stories he related. It was June 14, 1805, and Lewis had become the first white man to discover the Great Falls of the Missouri River the previous day. Lewis had just shot a buffalo and was watching blood stream from its mouth and nostrils when a large grizzly snuck within “20 steps before I discovered him.” The explorer, who hadn’t yet reloaded his rifle and had no trees to climb, wrote of the events that followed:

there was no place by means of which I could conceal myself from this monster untill I could charge my rifle; in this situation I thought of retreating in a brisk walk as fast as he was advancing untill I could reach a tree about 300 yards below me, but I had no sooner terned myself about but he pitched at me, open mouthed and full speed, I ran about 80 yards and found he gained on me fast, I then run into the water the idea struk me to get into the water to such debth that I could stand and he would be obliged to swim, and that I could in that situation defend myself with my espontoon.

Lewis wrote how he dashed into water until he was waist-deep and then turned to face his pursuer. When the bear reached the water’s edge, “he sudonly wheeled about as if frightened, declined to combat on such unequal grounds, and retreated with quite as great precipitation as he had just before pursued me.”

A deep silence came over Lewis not long after the strange bear encounter. He and his men made it to the Pacific Ocean, which should have been cause for celebration, but what Lewis thought or felt is unknown. He made fewer journal entries, which were more terse— during the year the men spent getting back from the Pacific, it appears he hardly wrote anything. If he had, perhaps we’d have a better understanding of the nature of the darkness that would consume him that night in 1809 at Grinder’s Inn. The grizzly pelt that lay on the floor of Lewis’s room likely belonged to an animal he’d shot on the upper Missouri River. Had the animal come for him, blood gushing from its mouth, with teeth bared? Did Lewis stand over the breathless carcass feeling he’d conquered the embodiment of the wilderness? In that cabin at Grinder’s Inn, did he remember the bear as he charged his brace of pistols and put a barrel to his own head?

The shot failed to kill him—which is hard to believe, considering how efficient a marksman he was. He placed the second pistol’s barrel to his chest, pulled the trigger, and then struggled out the door. That night’s progression of strange events continued as he called out for water and someone to heal his wounds. The only people said to have heard his pleas, Mrs. Grinder and her children, were too terrified to respond.

At first light Mrs. Grinder and other witnesses approached and slowly entered the room. They found Lewis with a razor in hand “busily engaged in cutting himself from head to foot.” He asked for water and complained about his strength, as it made it difficult for him to die. Not long after sunrise, lying atop the blood-soaked bearskin, he breathed his last.

MORE THAN THIRTY YEARS AFTER I ENCOUNTERED THE BEAR CARCASS IN a salmon stream with my dad, I pushed through the forest fringe and stood on a well-worn bear trail at the base of a mountain on Admiralty Island. I led the way, followed by my older brother, Luke, as we hiked through the rainforest. I tried to stay alert, as it was mid-September when bears are at their most dangerous, but my thoughts kept drifting back to Meriwether Lewis. I wondered if he had been carrying any sort of written report detailing the Corps of Discovery expedition when he killed himself. The White House swept his death under the rug. Some people had difficulty accepting his suicide and put forward theories that he had been murdered. I couldn’t get the image of Lewis mutilated, covered in blood, and lying on a grizzly skin out of my head.

When Luke and I reached the alpine, we split up to cover more ground. My freezer was full, but friends who had been too busy to do much hunting could use some venison. I was feeling so distracted that I decided to go exploring instead. I clambered up steep scree to the top of the mountain where there was almost zero chance of encountering a deer. It was a crisp, clear day, and when I reached the summit, a perfect 360-degree panorama of mountains, ocean, and glaciers surrounded me.

I was walking along when I placed a foot in a hole and stumbled. Before me stretched what we in Alaska call a grandfather trail—a place where multitudes of brown bears have stepped in the same tracks and worn holes several inches deep. These trails are all over brown bear country. Some are used for a season; others are traveled for generations. Biologists aren’t entirely sure why bears, generally being solitary animals, go out of their way to step in each other’s tracks. Often, the males urinate on their own feet and grind their paws into the earth to better leave their mark. Sometimes these trails appear suddenly in seemingly random locations and then vanish just as inexplicably. Other times they’re along major travel corridors. Many of the trails high in the mountains are ancient—some likely date back thousands of years, to when giant ice caps began rapidly melting away from Southeast Alaska.

I knelt and placed my hand above a hole that had been worn into the earth by hundreds, maybe thousands, of bears. I thought about how everything leaves a trail, whether it’s imprinted in the land, in the narratives we tell, or even in our blood. Meriwether Lewis, with the stories he brought back from the West, set the foundation for America’s relationship with brown bears. A trickle, then a flood, of pioneers followed his trail west, doing their best to eradicate the bear as they went.

As I stood near that hole, my skin crawled, and I got the feeling I was being watched. I pulled my hand away and scanned the area before walking along the edge of the trail until I could no longer distinguish it from the earth.